J. Peter Pham Prepared Statement at Hearing on “The Ongoing Struggle Against Boko Haram” June 11, 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boko Haram Beyond the Headlines: Analyses of Africa’S Enduring Insurgency

Boko Haram Beyond the Headlines: Analyses of Africa’s Enduring Insurgency Editor: Jacob Zenn Boko Haram Beyond the Headlines: Analyses of Africa’s Enduring Insurgency Jacob Zenn (Editor) Abdulbasit Kassim Elizabeth Pearson Atta Barkindo Idayat Hassan Zacharias Pieri Omar Mahmoud Combating Terrorism Center at West Point United States Military Academy www.ctc.usma.edu The views expressed in this report are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect those of the Combating Terrorism Center, United States Military Academy, Department of Defense, or U.S. Government. May 2018 Cover Photo: A group of Boko Haram fighters line up in this still taken from a propaganda video dated March 31, 2016. COMBATING TERRORISM CENTER ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Director The editor thanks colleagues at the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point (CTC), all of whom supported this endeavor by proposing the idea to carry out a LTC Bryan Price, Ph.D. report on Boko Haram and working with the editor and contributors to see the Deputy Director project to its rightful end. In this regard, I thank especially Brian Dodwell, Dan- iel Milton, Jason Warner, Kristina Hummel, and Larisa Baste, who all directly Brian Dodwell collaborated on the report. I also thank the two peer reviewers, Brandon Kend- hammer and Matthew Page, for their input and valuable feedback without which Research Director we could not have completed this project up to such a high standard. There were Dr. Daniel Milton numerous other leaders and experts at the CTC who assisted with this project behind-the-scenes, and I thank them, too. Distinguished Chair Most importantly, we would like to dedicate this volume to all those whose lives LTG (Ret) Dell Dailey have been afected by conflict and to those who have devoted their lives to seeking Class of 1987 Senior Fellow peace and justice. -

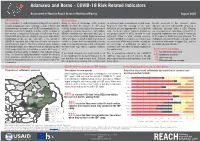

Adamawa and Borno - COVID-19 Risk Related Indicators

Adamawa and Borno - COVID-19 Risk Related Indicators Assessment of Hard-to-Reach Areas in Northeast Nigeria August 2020 Introduction Methodology The continuation of conflict in Northeast Nigeria has created a Using its Area of Knowledge (AoK) method, on settlement-wide circumstances in H2R areas. Results presented in this factsheet, unless complex humanitarian crisis, rendering sections of Borno and REACH monitors the situation in H2R areas Responses from KIs reporting on the same otherwise specified, represent the proportion of Adamawa states as hard to reach (H2R) for humanitarian actors. remotely through monthly multisector interviews in settlement are then aggregated to the settlement settlements assessed within a LGA. Findings Previous assessments illustrate how the conflict continues to accessible Local Government Area (LGA) capitals. level. The most common response provided by are only reported on LGAs where at least 5% of have severe consequences for people in H2R areas. People REACH interviews key informants (KIs) who 1) the greatest number of KIs is reported for each populated settlements and at least 5 settlements living in H2R areas, who are already facing severe and extreme are recently arrived internally displaced persons settlement. When no most common response in the respective LGA have been assessed. The humanitarian needs, are also vulnerable to the spread of (IDPs) who have left a H2R settlement in the last 3 could be identified, the response is considered as findings presented are indicative of broader trends COVID-19, especially due to the lack of health care services months, or 2) have been in contact with someone ‘no consensus’. While included in the calculations, in assessed settlements in August 2020, and are and information sources. -

How Boko Haram Became the Islamic State's West Africa

HOW BOKO HARAM BECAME THE ISLAMIC STATE’S WEST AFRICA PROVINCE J. Peter Pham ven before it burst into the headlines with its brazen April 2014 abduction of nearly three hundred schoolgirls from the town of Chibok in Nigeria’s northeast- Eern Borno State, sparking an unprecedented amount of social media communica- tion in the process, the Nigerian militant group Boko Haram had already distinguished itself as one of the fastest evolving of its kind, undergoing several major transformations in just over half a decade. In a very short period of time, the group went from being a small militant band focused on localized concerns and using relatively low levels of violence to a significant terrorist organization with a clearer jihadist ideology to a major insurgency seizing and holding large swathes of territory that was dubbed “the most deadly terrorist group in the world” by the Institute for Economics and Peace, based on the sheer number of deaths it caused in 2014.1 More recently, Boko Haram underwent another evolution with its early 2015 pledge of allegiance to the Islamic State and its subsequent rebranding as the “Islamic State West Africa Province” (ISWAP). The ideological, rhetorical, and operational choices made by Boko shifted consider- ably in each of these iterations, as did its tactics. Indeed the nexus between these three elements—ideology, rhetoric, and operations—is the key to correctly interpreting Boko Haram’s strategic objectives at each stage in its evolution, and to eventually countering its pursuit of these goals. Boko Haram 1.0 The emergence of the militant group that would become known as Boko Haram cannot be understood without reference to the social, religious, economic, and political milieu of J. -

FEWS NET Special Report: a Famine Likely Occurred in Bama LGA and May Be Ongoing in Inaccessible Areas of Borno State

December 13, 2016 A Famine likely occurred in Bama LGA and may be ongoing in inaccessible areas of Borno State This report summarizes an IPC-compatible analysis of Local Government Areas (LGAs) and select IDP concentrations in Borno State, Nigeria. The conclusions of this report have been endorsed by the IPC’s Emergency Review Committee. This analysis follows a July 2016 multi-agency alert, which warned of Famine, and builds off of the October 2016 Cadre Harmonisé analysis, which concluded that additional, more detailed analysis of Borno was needed given the elevated risk of Famine. KEY MESSAGES A Famine likely occurred in Bama and Banki towns during 2016, and in surrounding rural areas where conditions are likely to have been similar, or worse. Although this conclusion cannot be fully verified, a preponderance of the available evidence, including a representative mortality survey, suggests that Famine (IPC Phase 5) occurred in Bama LGA during 2016, when the vast majority of the LGA’s remaining population was concentrated in Bama Town and Banki Town. Analysis indicates that at least 2,000 Famine-related deaths may have occurred in Bama LGA between January and September, many of them young children. Famine may have also occurred in other parts of Borno State that were inaccessible during 2016, but not enough data is available to make this determination. While assistance has improved conditions in accessible areas of Borno State, a Famine may be ongoing in inaccessible areas where conditions could be similar to those observed in Bama LGA earlier this year. Significant assistance in Bama Town (since July) and in Banki Town (since August/September) has contributed to a reduction in mortality and the prevalence of acute malnutrition, though these improvements are tenuous and depend on the continued delivery of assistance. -

Nigeria Update to the IMB Nigeria

Progress in Polio Eradication Initiative in Nigeria: Challenges and Mitigation Strategies 16th Independent Monitoring Board Meeting 1 November 2017 London 0 Outline 1. Epidemiology 2. Challenges and Mitigation strategies SIAs Surveillance Routine Immunization 3. Summary and way forward 1 Epidemiology 2 Polio Viruses in Nigeria, 2015-2017 Past 24 months Past 12 months 3 Nigeria has gone 13 months without Wild Polio Virus and 11 months without cVDPV2 13 months without WPV 11 months – cVDPV2 4 Challenges and Mitigation strategies 5 SIAs 6 Before the onset of the Wild Polio Virus Outbreak in July 2016, there were several unreached settlements in Borno Borno Accessibility Status by Ward, March 2016 # of Wards in % Partially LGAs % Fully Accessible % Inaccessible LGA Accessible Abadam 10 0% 0% 100% Askira-Uba 13 100% 0% 0% Bama 14 14% 0% 86% Bayo 10 100% 0% 0% Biu 11 91% 9% 0% Chibok 11 100% 0% 0% Damboa 10 20% 0% 80% Dikwa 10 10% 0% 90% Gubio 10 50% 10% 40% Guzamala 10 0% 0% 100% Gwoza 13 8% 8% 85% Hawul 12 83% 17% 0% Jere 12 50% 50% 0% Kaga 15 0% 7% 93% Kala-Balge 10 0% 0% 100% Konduga 11 0% 64% 36% Kukawa 10 20% 0% 80% Kwaya Kusar 10 100% 0% 0% Mafa 12 8% 0% 92% Magumeri 13 100% 0% 0% Maiduguri 15 100% 0% 0% Marte 13 0% 0% 100% Mobbar 10 0% 0% 100% Monguno 12 8% 0% 92% Ngala 11 0% 0% 100% Nganzai 12 17% 0% 83% Shani 11 100% 0% 0% State 311 41% 6% 53% 7 Source: Borno EOC Data team analysis Four Strategies were deployed to expand polio vaccination reach and increase population immunity in Borno state SIAs RES2 RIC4 Special interventions 12 -

Información Para La Prensa Argelia

Información para la prensa Argelia Indonesia Irán Iraq Kuwait Libia Nigeria Qatar Arabia Saudita Emiratos Árabes Unidos República Bolivariana de Venezuela Estructura de la Organización I Fundación El primer movimiento hacia el establecimiento de la Organización de Países Exportadores de Petróleo tuvo lugar en 1949, cuando Venezuela se acercó a Irán, Irak, Kuwait y Arabia Saudita y les sugirió intercambiar puntos de vista y explorar posibilidades para entablar comunicación regular entre ellos. La necesidad de cooperación más cercana se hizo más aparente cuando, en 1959, las compañías petroleras unilateralmente redujeron el precio del crudo venezolano en 5 centavos de dólar y en 25 centavos de dólar por barril, y el del Medio Oriente en 18 centavos de dólar por barril. Como resultado, el primer Congreso Árabe Petrolero que se llevó a cabo en El Cairo adoptó una resolución invitando a las compañías petroleras a consultar con los gobiernos de los países productores antes de tomar unilateralmente cualquier decisión sobre los precios del petróleo, así como también para erigir el acuerdo general del establecimiento de una “Comisión de Consulta Petrolera”. En agosto de 1960 las compañías petroleras redujeron los precios del petróleo entre 10 y 14 centavos de dólar por barril. Al siguiente mes el gobierno de Irak invitó a Irán, Kuwait, Arabia Saudita y Venezuela a reunirse en Bagdad para discutir la reducción de precios del crudo producido por sus respectivos países. Como resultado, a partir del 10-14 de septiembre de 1960 se sostuvo una conferencia en Bagdad a la cual asistieron representantes de los gobiernos de Irán, Irak, Kuwait, Arabia Saudí y Venezuela. -

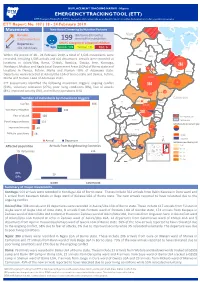

ETT Report No.107

DISPLACEMENT TRACKING MATRIX - Nigeria DTM Nigeria EMERGENCY TRACKING TOOL (ETT) DTM Emergency Tracking Tool (ETT) is deployed to track and provide up-to-date information on sudden displacement and other population movements ETT Report: No. 107 | 18 - 24 February 2019 Movements New Arrival Screening by Nutri�on Partners Abadam Arrivals: Children (6-59 months) Niger Lake Chad 1,505 individuals screened for malnutri�on 23 Kukawa 199 Mobbar MUAC category of screened children Departures: Guzamala 101 individuals Green: 174 Yellow: 19 Red: 6 Gubio Monguno Within the period of 18 - 24 February 2019, a total of 1,606 movements were Nganzai recorded, including 1,505 arrivals and 101 departures. Arrivals were recorded at Marte Ngala loca�ons in Askira/Uba, Bama, Chibok, Damboa, Gwoza, Jere, Konduga, Magumeri Maiduguri 283 Maiduguri, Mobbar and Ngala Local Government Areas (LGAs) of Borno state and 36 9 Jere Mafa loca�ons in Demsa, Fufore, Maiha and Numan LGAs of Adamawa state. Dikwa Kala/Balge Departures were recorded at Askira/Uba LGA of Borno state and Demsa, Fufore, Borno Konduga Maiha and Numan LGAs of Adamawa state. Kaga ETT assessments iden�fied the following movement triggers: ongoing conflict 564 Bama 76 (53%), voluntary reloca�on (27%), poor living condi�ons (8%), fear of a�acks (8%), improved security (3%), and military opera�ons (1%) Gwoza 23 Damboa 39 Number of individuals by movement triggers Cameroon Chibok 7 Biu Madagali Conflict 856 Askira/Uba Michika Voluntary reloca�on 439 Kwaya Kusar 19 Bayo Hawul 308 Mubi North Fear of a�ack 128 -

Nigeria – Complex Emergency JUNE 7, 2021

Fact Sheet #3 Fiscal Year (FY) 2021 Nigeria – Complex Emergency JUNE 7, 2021 SITUATION AT A GLANCE 206 8.7 2.9 308,000 12.8 MILLION MILLION MILLION MILLION Estimated Estimated Number of Estimated Estimated Projected Acutely Population People in Need in Number of IDPs Number of Food-Insecure w of Nigeria Northeast Nigeria in Nigeria Nigerian Refugees Population for 2021 in West Africa Lean Season UN – December 2020 UN – February 2021 UNHCR – February 2021 UNHCR – April 2021 CH – March 2021 Major OAG attacks on population centers in northeastern Nigeria—including Borno State’s Damasak town and Yobe State’s Geidam town—have displaced hundreds of thousands of people since late March. Intercommunal violence and OCG activity continue to drive displacement and exacerbate needs in northwest Nigeria. Approximately 12.8 million people will require emergency food assistance during the June-to-August lean season, representing a significant deterioration of food security in Nigeria compared with 2020. 1 TOTAL U.S. GOVERNMENT HUMANITARIAN FUNDING USAID/BHA $230,973,400 For the Nigeria Response in FY 2021 State/PRM2 $13,500,000 For complete funding breakdown with partners, see detailed chart on page 7 Total $244,473,400 1 USAID’s Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance (USAID/BHA) 2 U.S. Department of State Bureau for Population, Refugees, and Migration (State/PRM) 1 KEY DEVELOPMENTS Violence Drives Displacement and Constrains Access in the Northeast Organized armed group (OAG) attacks in Adamawa, Borno, and Yobe states have displaced more than 200,000 people since March and continue to exacerbate humanitarian needs and limit relief efforts, according to the UN. -

Odo/Ota Local Government Secretariat, Sango - Agric

S/NO PLACEMENT DEPARTMENT ADO - ODO/OTA LOCAL GOVERNMENT SECRETARIAT, SANGO - AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 1 OTA, OGUN STATE AGEGE LOCAL GOVERNMENT, BALOGUN STREET, MATERNITY, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 2 SANGO, AGEGE, LAGOS STATE AHMAD AL-IMAM NIG. LTD., NO 27, ZULU GAMBARI RD., ILORIN AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 3 4 AKTEM TECHNOLOGY, ILORIN, KWARA STATE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 5 ALLAMIT NIG. LTD., IBADAN, OYO STATE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 6 AMOULA VENTURES LTD., IKEJA, LAGOS STATE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING CALVERTON HELICOPTERS, 2, PRINCE KAYODE, AKINGBADE MECHANICAL ENGINEERING 7 CLOSE, VICTORIA ISLAND, LAGOS STATE CHI-FARM LTD., KM 20, IBADAN/LAGOS EXPRESSWAY, AJANLA, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 8 IBADAN, OYO STATE CHINA CIVIL ENGINEERING CONSTRUCTION CORPORATION (CCECC), KM 3, ABEOKUTA/LAGOS EXPRESSWAY, OLOMO - ORE, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 9 OGUN STATE COCOA RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF NIGERIA (CRIN), KM 14, IJEBU AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 10 ODE ROAD, IDI - AYANRE, IBADAN, OYO STATE COKER AGUDA LOCAL COUNCIL, 19/29, THOMAS ANIMASAUN AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 11 STREET, AGUDA, SURULERE, LAGOS STATE CYBERSPACE NETWORK LTD.,33 SAKA TIINUBU STREET. AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 12 VICTORIA ISLAND, LAGOS STATE DE KOOLAR NIGERIA LTD.,PLOT 14, HAKEEM BALOGUN STREET, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING OPP. TECHNICAL COLLEGE, AGIDINGBI, IKEJA, LAGOS STATE 13 DEPARTMENT OF PETROLEUM RESOURCES, 11, NUPE ROAD, OFF AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 14 AHMAN PATEGI ROAD, G.R.A, ILORIN, KWARA STATE DOLIGERIA BIOSYSTEMS NIGERIA LTD, 1, AFFAN COMPLEX, 1, AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 15 OLD JEBBA ROAD, ILORIN, KWARA STATE Page 1 SIWES PLACEMENT COMPANIES & ADDRESSES.xlsx S/NO PLACEMENT DEPARTMENT ESFOOS STEEL CONSTRUCTION COMPANY, OPP. SDP, OLD IFE AGRIC. & BIO. ENGINEERING 16 ROAD, AKINFENWA, EGBEDA, IBADAN, OYO STATE 17 FABIS FARMS NIGERIA LTD., ILORIN, KWARA STATE AGRIC. -

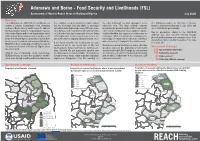

Adamawa and Borno - Food Security and Livelihoods (FSL) Assessment of Hard-To-Reach Areas in Northeast Nigeria July 2020

Adamawa and Borno - Food Security and Livelihoods (FSL) Assessment of Hard-to-Reach Areas in Northeast Nigeria July 2020 Overview The continuation of conflict in Northeast Nigeria has in accessible Local Government Area (LGA) capitals the same settlement are then aggregated to the The findings presented are indicative of broader created a complex humanitarian crisis, rendering with key informants (KIs) who either (1) are newly settlement level. The most common response trends in assessed settlements in July 2020, and sections of Borno state as hard to reach. To address arrived internally displaced persons (IDPs) who have provided by the greatest number of KIs is reported for are not statistically generalisable. information gaps facing the humanitarian response left a hard-to-reach settlement in the last 3 months each settlement. When no most common response Due to precautions related to the COVID-19 in Northeast Nigeria and inform humanitarian actors or (2) KIs who have had contact with someone living could be identified, the response is considered as ‘no outbreak, data was collected remotely through on the demographics of households in hard-to-reach or having been in a hard-to-reach settlement in the consensus’. While included in the calculations, the phone based interviews with assistance from local areas of Northeast Nigeria, as well as to identify their last month (traders, migrants, family members, etc.)1 percentage of settlements for which no consensus stakeholders. Data collection took place from June needs, access to services and movement intentions, was reached is not displayed in the results below. If not stated otherwise, the recall period for each 1st to June 30th. -

Procurement Plan

PROCUREMENT PLAN (Textual Part) Project information: Country: Nigeria Public Disclosure Authorized Project Name: Multi-Sectoral Crisis Recovery Project for North East Nigeria (MCRP) P- Number: P157891 Project Implementation Agency: MCRP PCU (Federal and States) Date of the Procurement Plan: Updated -December 22, 2017. Period covered by this Procurement Plan: From 01/12/2018 – 30/06/2019. Public Disclosure Authorized Preamble In accordance with paragraph 5.9 of the “World Bank Procurement Regulations for IPF Borrowers” (July 2016) (“Procurement Regulations”) the Bank’s Systematic Tracking and Exchanges in Procurement (STEP) system will be used to prepare, clear and update Procurement Plans and conduct all procurement transactions for the Project. This textual part along with the Procurement Plan tables in STEP constitute the Procurement Plan for the Project. The following conditions apply to all procurement activities in the Procurement Plan. The other elements of the Procurement Plan as required under paragraph 4.4 of the Procurement Regulations are set forth in STEP. Public Disclosure Authorized The Bank’s Standard Procurement Documents: shall be used for all contracts subject to international competitive procurement and those contracts as specified in the Procurement Plan tables in STEP. National Procurement Arrangements: In accordance with paragraph 5.3 of the Procurement Regulations, when approaching the national market (as specified in the Procurement Plan tables in STEP), the country’s own procurement procedures may be used. When the Borrower uses its own national open competitive procurement arrangements as set forth in the FGN Public Procurement Act 2007; such arrangements shall be subject to paragraph 5.4 of the Procurement Regulations. -

State, Octoberto Decembe& 1983. 6.I Introduction Gongoi

189 CHAPTER SIX ASTHE THIRD CTVILIAN GOVERNOROF GONGOI.A STATE, OCTOBERTO DECEMBE& 1983. 6.I INTRODUCTION l. GONGOI-A STATE UNDER COL. MUHAMMADUIEGA The General Murtala Mohammed Administration created Gongola State in February 1976 along with six other states. The state had Lt. Col. Muhammadu Jega (now Major General Rtd.) as its fust Military Governor. To all Gongolans, the creation marked the beginning of social, economic and political challenges leading to general development. Carved out of the defunct North-Eastem State (comprising former Bauchi, Adamawa, Borno and Sardauna Provinces) and part of Benue-Plateau State (i.e. the former Wukari Division), Gongola State had a land mass of 102,068 sq kilometers which made it the second latgest state in the Federation. It is located within latitude 11" South and longitude 9%"West and 14" East with a projected population of 4.6 million people (1983). Gongola State shared comnon borders with Plateau and Benue sates. Seven administrative divisions comprising Adamawa, Numan, Mubi, Wukari; Ganye, Jalingo and Sardauna made up the state at its inception. At the initial stage, the st2te capital, Yola, and all the seven adrninistrative headquarters had few or no modern infrastructutal faciiities. Mosi facilities therefore had to be developed from scratch in all parts of the sate. To this end, a Task Fotce Committee was esablished undet the chaitmanship of Alhaji Abubakar Abdullahi @aban Larai) to scout for both of6ce and residential iccommodation for the more than 5,000 civil servants deployed to the state. Similarly, the committee had to device means of srilizilg 6axi6fly, the few movable assets inherited from the former North-Eastern State.