Peter Nasmyth's Georgia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

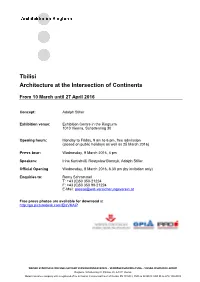

Tbilisi Architecture at the Intersection of Continents

Tbilisi Architecture at the Intersection of Continents From 10 March until 27 April 2016 Concept: Adolph Stiller Exhibition venue: Exhibition Centre in the Ringturm 1010 Vienna, Schottenring 30 Opening hours: Monday to Friday, 9 am to 6 pm, free admission (closed on public holidays as well as 25 March 2016) Press tour: Wednesday, 9 March 2016, 4 pm Speakers: Irina Kurtishvili, Rostyslaw Bortnyk, Adolph Stiller Official Opening Wednesday, 9 March 2016, 6.30 pm (by invitation only) Enquiries to: Romy Schrammel T: +43 (0)50 350-21224 F: +43 (0)50 350 99-21224 E-Mail: [email protected] Free press photos are available for download at http://go.picturedesk.com/ElaVKAiP WIENER STÄDTISCHE WECHSELSEITIGER VERSICHERUNGSVEREIN – VERMÖGENSVERWALTUNG – VIENNA INSURANCE GROUP Ringturm, Schottenring 30, PO Box 80, A-1011 Vienna Mutual insurance company with a registered office in Vienna; Commercial Court of Vienna; FN 101530 i; DVR no 0688533; VAD ID no ATU 15363309 Tbilisi – architecture at the crossroads of Europe and Asia The name Tbilisi is derived from the old Georgian word “tbili”, which roughly translates as “warm” and refers to the region’s numerous hot sulphur springs that reach temperatures of up to 47°C. The area was first settled in the early Bronze Age, and ancient times also left their mark: in Greek mythology, the Argonauts sailed to Colchis, which was part of Georgia, in their quest for the Golden Fleece. In the fifth century King Vakhtang I Gorgasali turned the existing settlement into a fortified town, and in the first half of that century Tbilisi was recognised as the second capital of the kings of Kartli in eastern Georgia. -

Javakheti After the Rose Revolution: Progress and Regress in the Pursuit of National Unity in Georgia

Javakheti after the Rose Revolution: Progress and Regress in the Pursuit of National Unity in Georgia Hedvig Lohm ECMI Working Paper #38 April 2007 EUROPEAN CENTRE FOR MINORITY ISSUES (ECMI) ECMI Headquarters: Schiffbruecke 12 (Kompagnietor) D-24939 Flensburg Germany +49-(0)461-14 14 9-0 fax +49-(0)461-14 14 9-19 Internet: http://www.ecmi.de ECMI Working Paper #38 European Centre for Minority Issues (ECMI) Director: Dr. Marc Weller Copyright 2007 European Centre for Minority Issues (ECMI) Published in April 2007 by the European Centre for Minority Issues (ECMI) ISSN: 1435-9812 2 Table of Contents I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................4 II. JAVAKHETI IN SOCIO-ECONOMIC TERMS ...........................................................5 1. The Current Socio-Economic Situation .............................................................................6 2. Transformation of Agriculture ...........................................................................................8 3. Socio-Economic Dependency on Russia .......................................................................... 10 III. DIFFERENT ACTORS IN JAVAKHETI ................................................................... 12 1. Tbilisi influence on Javakheti .......................................................................................... 12 2. Role of Armenia and Russia ............................................................................................. 13 3. International -

Gruzie, Země Rozkládající Se Na Jih Od Hřbetu Velkého Kavkazu, Na

FAKULTA SOCIÁLNÍCH STUDIÍ MASARYKOVY UNIVERZITY Katedra mezinárodních vztahů a evropských studií Příčiny politické, bezpečnostní a hospodářské krize Gruzie od nabytí nezávislosti v roce 1991 do příchodu současné administrativy Rigorózní práce Zpracoval: Ivan Jestřáb, 2010 Čestné prohlášení Prohlašuji tímto, ţe jsem rigorózní práci na téma „Příčiny politické, bezpečnostní a hospodářské krize Gruzie od nabytí nezávislosti v roce 1991 do příchodu současné administrativy― zpracoval sám pouze s vyuţitím pramenů v práci uvedených. Ivan Jestřáb 2 Autor by rád ocenil pomoc, které se mu dostalo od pracovníků katedry mezinárodních vztahů a evropských studií FSS MU, zejména od doc. PhDr. Zdenka Kříţe, Ph.D., bez jehoţ obětavého vedení, rad a doporučení by bylo zpracování této práce mnohem obtíţnější. Poděkování patří také vedoucímu katedry PhDr. Petru Suchého Ph.D. za jeho cenné rady a podporu. 3 Obsah Úvod 6 Stručná historie Gruzie 11 Území Gruzie v předfeudálním období 12 Přijetí křesťanství jako státního náboţenství 13 Nástup rodu Bagrationovců 14 Další útoky cizích nájezdníků, oslabování státu 17 Georgievský traktát, podřízení Gruzie Rusku 18 Tři roky samostatné gruzínské republiky a přičlenění k Sovětskému Rusku 20 Obnovení samostatnosti, budování nového státu 20 Otázka autonomie Jiţní Osetie ve 20. létech 25 Konec sovětské Gruzie; dosaţení nezávislosti, první problémy nového státu 30 Nástup vedení Zviada Gamsachurdii 30 Boj o moc v Tbilisi 36 Ekonomická situace v Gruzii 40 Počátky ekonomické reformy a přechod od příkazové ekonomiky na počáteční stádium ekonomiky trţní 40 Reformy jednotlivých sektorů hospodářství v 90. létech 47 Ekonomické ukazatele a tendence vývoje v hodnoceném období 52 Působení mezinárodních finančních institucí v Gruzii 55 Mafianizace ekonomiky 61 Ozbrojený konflikt v Jiţní Osetii v 90. -

Annexation of Georgia in Russian Empire

1 George Anchabadze HISTORY OF GEORGIA SHORT SKETCH Caucasian House TBILISI 2005 2 George Anchabadze. History of Georgia. Short sketch Above-mentioned work is a research-popular sketch. There are key moments of the history of country since ancient times until the present moment. While working on the sketch the author based on the historical sources of Georgia and the research works of Georgian scientists (including himself). The work is focused on a wide circle of the readers. გიორგი ანჩაბაძე. საქართველოს ისტორია. მოკლე ნარკვევი წინამდებარე ნაშრომი წარმოადგენს საქართველოს ისტორიის სამეცნიერ-პოპულარულ ნარკვევს. მასში მოკლედაა გადმოცემული ქვეყნის ისტორიის ძირითადი მომენტები უძველესი ხანიდან ჩვენს დრომდე. ნარკვევზე მუშაობისას ავტორი ეყრდნობოდა საქართველოს ისტორიის წყაროებსა და ქართველ მეცნიერთა (მათ შორის საკუთარ) გამოკვლევებს. ნაშრომი განკუთვნილია მკითხველთა ფართო წრისათვის. ISBN99928-71-59-8 © George Anchabadze, 2005 © გიორგი ანჩაბაძე, 2005 3 Early Ancient Georgia (till the end of the IV cen. B.C.) Existence of ancient human being on Georgian territory is confirmed from the early stages of anthropogenesis. Nearby Dmanisi valley (80 km south-west of Tbilisi) the remnants of homo erectus are found, age of them is about 1,8 million years old. At present it is the oldest trace in Euro-Asia. Later on the Stone Age a man took the whole territory of Georgia. Former settlements of Ashel period (400–100 thousand years ago) are discovered as on the coast of the Black Sea as in the regions within highland Georgia. Approximately 6–7 thousands years ago people on the territory of Georgia began to use as the instruments not only the stone but the metals as well. -

Georgian Country and Culture Guide

Georgian Country and Culture Guide მშვიდობის კორპუსი საქართველოში Peace Corps Georgia 2017 Forward What you have in your hands right now is the collaborate effort of numerous Peace Corps Volunteers and staff, who researched, wrote and edited the entire book. The process began in the fall of 2011, when the Language and Cross-Culture component of Peace Corps Georgia launched a Georgian Country and Culture Guide project and PCVs from different regions volunteered to do research and gather information on their specific areas. After the initial information was gathered, the arduous process of merging the researched information began. Extensive editing followed and this is the end result. The book is accompanied by a CD with Georgian music and dance audio and video files. We hope that this book is both informative and useful for you during your service. Sincerely, The Culture Book Team Initial Researchers/Writers Culture Sara Bushman (Director Programming and Training, PC Staff, 2010-11) History Jack Brands (G11), Samantha Oliver (G10) Adjara Jen Geerlings (G10), Emily New (G10) Guria Michelle Anderl (G11), Goodloe Harman (G11), Conor Hartnett (G11), Kaitlin Schaefer (G10) Imereti Caitlin Lowery (G11) Kakheti Jack Brands (G11), Jana Price (G11), Danielle Roe (G10) Kvemo Kartli Anastasia Skoybedo (G11), Chase Johnson (G11) Samstkhe-Javakheti Sam Harris (G10) Tbilisi Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Workplace Culture Kimberly Tramel (G11), Shannon Knudsen (G11), Tami Timmer (G11), Connie Ross (G11) Compilers/Final Editors Jack Brands (G11) Caitlin Lowery (G11) Conor Hartnett (G11) Emily New (G10) Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Compilers of Audio and Video Files Keti Chikovani (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator, PC Staff) Irakli Elizbarashvili (IT Specialist, PC Staff) Revised and updated by Tea Sakvarelidze (Language and Cross-Culture Coordinator) and Kakha Gordadze (Training Manager). -

Weekly News Digest on Georgia June 29-July 6, 2021

Compiled by: Aleksandre Weekly News Digest on Georgia Davitashvili June 29-July 6, 2021 Compiled on: July 7, 2021 Content Internal Affairs Internal Affairs Political Developments Political Developments 1. Parliament Amends Election Code 1. Parliament Amends Georgian Parliament adopted late on June 28, with 86 votes to three, Election Code amendments to the Election Code, a reform envisaged in the April-19 EU- 2. Central Election Commission Chair brokered deal signed by the ruling Georgian Dream and most of the opposition Resigns parties. 3. Orthodox Church Speaks The amendments introduce new rules to the election system, pre-election Out Against Pride Week campaigning and staffing the Election Administrations. As per the changes, the 4. Diplomatic Missions Central Election Commission Chair will be nominated by the President and Urge Gov’t to Protect approved by 2/3 of votes in the legislature. The number of CEC members Pride Activists increases from 12 to 17, of which eight will be “professional” and nine will be 5. President Defends Tbilisi Pride party-selected. The CEC Chair will have two deputies, one “professional” and one 6. 20 detained while trying selected from the opposition-selected members. to disrupt Tbilisi Pride The changed legislation also increases proportional representation in local events elections and imposes a 40% threshold in the majoritarian part. For example in 7. Former MP Accused of Tbilisi City Council (Sakrebulo), out of 50 members 40 will be elected through Sexual Violence Released proportional lists, while 10 will be majoritarian – as opposed to the previous on Bail allocation of 25 – 25 (Civil.ge, June 29, 2021). -

TTT - Tips for Tbilisi Travelers

TTT - Tips for Tbilisi Travelers Venue V.Sarajishvili Tbilisi State Conservatoire (TSC) Address: Griboedov str 8-10, Tbilisi 0108, Georgia Brief info about the city Capital of Georgia, Tbilisi, population about 1.5 million people and 1.263.489 and 349sq.km (135 sq.miles), is one of the most ancient cities in the world. The city is favorably situated on both banks of the Mtkvari (Kura) River and is protected on three sides by mountains. On the same latitude as Barcelona, Rome, and Boston, Tbilisi has a temperate climate with an average temperature of 13.2C (56 F). Winters are relatively mild, with only a few days of snow. January is the coldest month with an average temperature of 0.9 C (33F). July is the hottest month with 25.2 C (77 F). Autumn is the loveliest season of a year. Flights Do not be scared to fly to Georgia! You will most probably need a connecting flight to the cities which have direct flights and you will have to face several hours of trips probably arriving during the night, but it will be worth the effort! Direct Flights To Tbilisi are from Istanbul, Munich, Warsaw, Riga, Vienna, Moscow, London: Turkish Airlines - late as well as "normal" arrivals (through Istanbul or Gokcen) Lufthansa (Munich) Baltic airlines (Riga) Polish airlines lot (Warsaw) Aeroflot (Moscow) Ukrainian Airlines - (Kiev) Pegasus - (Istanbul) Georgian Airlines (Amsterdam, Paris, Vienna) Aegean (Athens) Belavia - through Minsk Airzena - through London from may Parkia - through Telaviv Atlas global - through Istanbul Direct flights to Kutaisi ( another city in west Georgia and takes 3 hr driving to the capital) - these are budget flights and are much more cheaper – shuttle buses to Tbiisi available Wizzair flies to Budapest London Vilnius kaunas Saloniki Athens different cities from Germany - berlin, dortmund, minuch, Milan katowice, warsaw Ryanair - from august Air berlin - from august Transfer from the airport - Transfer from the airport to the city takes ca. -

Colour Protest in Post-War Georgia – Chronology of Rose Revolution

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS DANUBIUS Vol. 11, no. 2/2018 Colour Protest in Post-War Georgia – Chronology of Rose Revolution Nino Machurishvili1 Abstract: The aim of this paper is to review political and material deprivation as a basis for social protest during the pre – revolution period in Georgia, within the framework of Relative Deprivation theory. The linkage between relative deprivation and the Gini coefficient, as well type of existing political regime and Soviet past is considered. The originality of this paper is conditioned by the new approach to Colour Revolutions, forgotten concept of Relative Deprivation is revisited and applied to the Rose Revolution in order to explain, why individuals decided to join demonstrations, as previous studies are considered a precondition for comprehending social protest against rigged elections, either the lack of democracy. This research is based on a qualitative research methodology, the basic methodological approach being the method of the case study. Among with in – depth interviews based on projective techniques with respondents grouped according to their attitudes towards Rose Revolution, quantitative data of World Bank and Freedom House coefficients are also reviewed. Empirical analysis of interviews proves the existence of political and material deprivation between social groups for the research period. This research shows the methodological value of Relative Deprivation to explain social movement motivation for the Rose Revolution in Georgia. Keywords: Colour Revolutions; Relative Deprivation; Social Inequality; Hybrid Regime Introduction 1.1. Relative Deprivation and Individual Decision to Protest This paper contributes to better understanding of causes Colour Revolutions in Post – Soviet space. It specifically deals with the case of Rose Revolution – peaceful change of Government in Georgia in 2003. -

Traditional Religion and Political Power: Examining the Role of the Church in Georgia, Armenia, Ukraine and Moldova

Traditional religion and political power: Examining the role of the church in Georgia, Armenia, Ukraine and Moldova Edited by Adam Hug Traditional religion and political power: Examining the role of the church in Georgia, Armenia, Ukraine and Moldova Edited by Adam Hug First published in October 2015 by The Foreign Policy Centre (FPC) Unit 1.9, First Floor, The Foundry 17 Oval Way, Vauxhall, London SE11 5RR www.fpc.org.uk [email protected] © Foreign Policy Centre 2015 All rights reserved ISBN 978-1-905833-28-3 ISBN 1-905833-28-8 Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors alone and do not represent the views of The Foreign Policy Centre or the Open Society Foundations. Printing and cover art by Copyprint This project is kindly supported by the Open Society Foundations 1 Acknowledgements The editor would like to thank all of the authors who have kindly contributed to this collection and provided invaluable support in developing the project. In addition the editor is very grateful for the advice and guidance of a number of different experts including: John Anderson, Andrew Sorokowski, Angelina Zaporojan, Mamikon Hovsepyan, Beka Mindiashvili, Giorgi Gogia, Vitalie Sprinceana, Anastasia Danilova, Artyom Tonoyan, Dr. Katja Richters, Felix Corley, Giorgi Gogia, Bogdan Globa, James W. Warhola, Mamikon Hovsepyan, Natia Mestvirishvil, Tina Zurabishvili and Vladimir Shkolnikov. He would like to thank colleagues at the Open Society Foundations for all their help and support without which this project would not have been possible, most notably Viorel Ursu, Michael Hall, Anastasiya Hozyainova and Eleanor Kelly. -

BATTLESTAR GALACTICA and PHILOSOPHY:Knowledge Here

BATTLESTAR GALACTICA AND PHILOSOPHY The Blackwell Philosophy and PopCulture Series Series editor William Irwin A spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down, and a healthy help- ing of popular culture clears the cobwebs from Kant. Philosophy has had a public relations problem for a few centuries now. This series aims to change that, showing that philosophy is relevant to your life—and not just for answering the big questions like “To be or not to be?” but for answering the little questions: “To watch or not to watch South Park?” Thinking deeply about TV, movies, and music doesn’t make you a “complete idiot.” In fact it might make you a philosopher, someone who believes the unexamined life is not worth living and the unexamined cartoon is not worth watching. Edited by Robert Arp Edited by William Irwin Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski Edited by Jason Holt Edited by Sharon M. Kaye Edited by Jennifer Hart Weed, Richard Davis, and Ronald Weed BATTLESTAR GALACTICA AND PHILOSOPHY:Knowledge Here Begins Out There Edited by Jason T. Eberl Forthcoming the office and philosophy: scenes from the unexamined life Edited by J. Jeremy Wisnewski BATTLESTAR GA LACTICA AND PHILOSOPHY KNOWLEDGE HERE BEGINS OUT THERE EDITED BY JASON T. EBERL © 2008 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd blackwell publishing 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148–5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia The right of Jason T. Eberl to be identified as the author of the editorial material in this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988. -

Battlestar Galactica

Institutionen för studier av samhällsutveckling och kultur – ISAK LiU Norrköping Battlestar Galactica - Ett mänskligt universum Oscar Larsson Kandidatuppsats från programmet Kultur, samhälle, mediegestaltning 2008 Linköpings Universitet, Campus Norrköping, 601 74 Norrköping ISAK-Instutionen för studier av samhällsutveckling och kultur ISRN LIU-ISAK/KSM-G -- 09/02 -- SE Handledare: Michael Godhe Nyckelord: Battlestar Galactica, Battlestar, BG, Science Fiction, SF, Sci-Fi, Sci Fi, det mänskliga, människan, religion. Sammanfattning: Science Fiction har sedan sin uppkomst gestaltat samhället och de samhällsfrågor som för sin tid är aktuella. Alltifrån ifall människans existens är kroppslig eller andlig, till vad som händer när livsformer från andra planeter kommer till Jorden, har diskuteras i Science Fiction. I tv- serien Battlestar Galactica gestaltas och problematiseras vår samtid. Genom att flytta mänskligheten från Jorden och ut i rymden, där de konfronteras med en mängd etiska och moraliska frågor – tvingade att se över vad de själva är och vad de håller på att bli. Undersökningen avser att besvara frågor kring hur BG gestaltar människan och hennes förhållande till etik, moral, politik och religion. 1. INLEDNING 1 2. SYFTE & FRÅGSTÄLLNINGAR 2 3. DISPOSITION 3 4. TEORETISKA OCH METODOLOGISKA PERSPEKTIV 4 4.1 Forskningsfält 4 4.2 Representationsbegreppet 5 4.3 Kritiska ingångar 6 4.4 Metod och urval 8 5. DET MÄNSKLIGA 10 6. SCIENCE FICTION 14 7. ANALYTISK DEL 1: BATTLESTAR GALACTICA SOM ETT NARRATIVT UNIVERSUM 18 7.1 Mänskliga huvudkaraktärer 18 7.2 Cylonska huvudkaraktärer 20 7.3 Miniserien 22 7.4 Säsong 1 23 7.5 Säsong 2 23 7.6 Säsong 3 24 7.7 Battlestar Galactica: Razor 25 7.8 Säsong 4 25 7.9 Generell analys 26 8. -

WORLD REPORT 2021 EVENTS of 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH 350 Fifth Avenue New York, NY 10118-3299 HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH WORLD REPORT 2021 EVENTS OF 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH 350 Fifth Avenue New York, NY 10118-3299 HUMAN www.hrw.org RIGHTS WATCH This 31st annual World Report summarizes human rights conditions in nearly 100 countries and territories worldwide in 2020. WORLD REPORT It reflects extensive investigative work that Human Rights Watch staff conducted during the year, often in close partnership with 2021 domestic human rights activists. EVENTS OF 2020 Human Rights Watch defends HUMAN the rights of people worldwide. RIGHTS WATCH We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Copyright © 2021 Human Rights Watch Human Rights Watch began in 1978 with the founding of its Europe and All rights reserved. Central Asia division (then known as Helsinki Watch). Today it also Printed in the United States of America includes divisions covering Africa, the Americas, Asia, Europe and Central ISBN is 978-1-64421-028-4 Asia, the Middle East and North Africa, and the United States. There are thematic divisions or programs on arms; business and human rights; Cover photo: Kai Ayden, age 7, marches in a protest against police brutality in Atlanta, children’s rights; crisis and conflict; disability rights; the environment and Georgia on May 31, 2020 following the death human rights; international justice; lesbian, gay, bisexual, and of George Floyd in police custody. transgender rights; refugee rights; and women’s rights.