“Can't Help Singing”: the “Modern” Opera Diva In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

How do I look? Viewing, embodiment, performance, showgirls, and art practice. CARR, Alison J. Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/19426/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/19426/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. How Do I Look? Viewing, Embodiment, Performance, Showgirls, & Art Practice Alison Jane Carr A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ProQuest Number: 10694307 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10694307 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Declaration I, Alison J Carr, declare that the enclosed submission for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, and consisting of a written thesis and a DVD booklet, meets the regulations stated in the handbook for the mode of submission selected and approved by the Research Degrees Sub-Committee of Sheffield Hallam University. -

Torrance Herald

THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 21. 1935 Page 4 TORRANCE IfBRALD, Torrancp,-California BRITISH STAR of "Evergreen" is On the Double Bill At Fox Redondo Three Scintillating Stars Shine at Torrance "Bordertown" with Paul Muni FILM FIND Starting Sunday A Ucnn W. Levy romance as Opens at Lomita Tonight 1 »yinpalhctlcally treated na memorable Mm. MoonllBht." "fiapRgrutiflu' *«l<1 to embrace much splendor- as bus ever been crowded ,'irito" one iiTuittcal film, an a cant ill real favorites are .<ai to b'1 the ingredients of Cjaumon Uritlsh's currfnt offering at the Toiranre Theatre, Jessie Mat thews in "Kvcrsrrcen." The pic turn's <-ni,'UBc>mrnt will run thret nlchts starting tonight, as jmniun tu the feature, "Forsaking All Others." Miss Matthews Is the newest and one of the most sensatlona ' film finds of G. B. Production! :md lias had an enviable reputa- lio __ fit London previous to her eleva tion i', film .stardom. She played a bu!i<l y.-ar on the stage In "Ei green" )..-fore it was 1 transfel to tin- films. West of the Pecos" Opens Not'Sjnce "Dinner At Eight" motion picture created as much Tonight at Plaza Theatre Ivance discussion as Metro-Gold- yn - Mayor's newest offering, Hailed as the talking screen's two greatest portrayer* of emo'tion,, "Forsaking All Others," .which Barnum and His Tippling Aid< Paul Muni and Sette Davis smilingly regard the result of their greatest ihown tonight, Friday and,Sat dramaticmaic effort, the Warner Bros,ros, prouconproduction "Border-town,", in whichc urday at the Torrance Theatre star of ''I Am a Fugitive From the Chain Gang" and the sensatio i-ith a cast headed by three of "Of Human Bondage" reach new stellar heights. -

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers NMAH.AC.0584 Reuben Jackson and Wendy Shay 2015 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Music Manuscripts and Sheet Music, 1919 - 1973................................... 5 Series 2: Photographs, 1939-1990........................................................................ 21 Series 3: Scripts, 1957-1981.................................................................................. 64 Series 4: Correspondence, 1960-1996................................................................. -

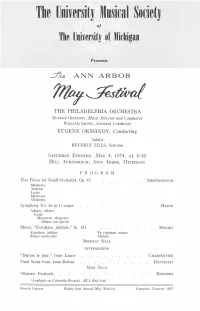

The Uuiversitj Musical Souietj of the University of Michigan

The UuiversitJ Musical SouietJ of The University of Michigan Presents ANN ARBOR THE PHILADELPHIA ORCHESTRA E UGENE ORMANDY , Music Director and Conduct01' WILLIAM SMITH, Assistant Conductor EUGENE ORMANDY, Conducting Soloist BEVERLY SILLS, Soprano SATURDAY EVENING , MAY 4, 1974, AT 8 :30 HILL AUDITORIUM , ANN ARBOR , MICHIGAN PROGRAM Five Pieces for Small Orchestra, Op. 42 SHOSTAKOVI CH Moderato Andante Largo Moderato Allegretto Symphony No. 88 in G major HAYDN Adagio; allegro La rgo Menuetto : a llegretto Allegro con spirito Motet, "Exsultate, jubilate," K. 165 MOZART Exsul tate, jubilate Tu virginum corona Fulge t arnica di es .-\lIelu ja BEVERL Y S ILLS IN TERiVIISSION " Depuis Ie jour," fr om Louise CHARPENTIER Fin al Scene from Anna Bolena DON IZETTl MISS SILLS ';'Roman Festivals R ESPIGHI *A vailable on Columbia R ecords RCA R ed Seal F ourth Concert Eighty-first Annua l May Festi n ll Complete Conce rts 3885 PROGRAM NOTES by G LENN D. MCGEOCH Five Pieces for Small Orchestra, Op. 42 DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906- ) The Fi ve Pieces, written by Shostakovich at the age of twenty-nine, were never mentioned or listed among his major works, until Ivan M artynov, in a monograph ( 1947) referred to them as "Five Fragments for Orchestra, 193 5 manuscript, op. 42." A conflict, which had begun to appear between the compose r's natura l, but advanced expression, and the Soviet official sanction came to a climax in 1934 wh en he produced his "avant guarde" opera Lady Ma cbeth of Mzensk. He was accuse d of "deliberate musical affectation " and of writing "un Soviet, eccent ric music, founded upon formalistic ideas of bourge ois musical conce ptions." Responding to this official castigation, he wrote a se ries of short, neoclassic, understated works, typical of the Fi ve Pieces on tonight's program. -

Composers Mascagni and Leoncavallo Biography

Cavalleria Rusticana Composer Biography: Pietro Mascagni Mascagni was an Italian composer born in Livorno on December 7, 1863. His father was a baker and dreamed of a career as a lawyer for his son, but following the good reception obtained by Mascagni’s first compositions was persuaded to allow him to study music at the Milan Conservatoire, where his teachers included Amilcare Ponchielli and Michele Saladino, and where he shared a furnished room with his fellow-student Giacomo Puccini. His first compositions won him financial support to study at the Milan Conservatory. He was of a rebellious nature and intolerant of discipline, and in 1885 he left the Conservatoire to join a modest operetta company as conductor. He became part of the Compagnia Maresca and, together with his future wife, Lina Carbognani, settled in Cerignola (Apulia) in 1886, where he formed a symphony orchestra. Here Mascagni composed at a single stroke, in only two months, the one-act opera Cavalleria rusticana, based on the short story by Verga, which was to win him the first prize in the Second Sonzogno Competition for new operas. The innovative strength of the opera and the resounding worldwide success which followed its first performance (1890, Teatro Costanzi, Rome) marked the beginning of an artistic life rich in achievements and satisfactions, both as composer and as conductor. He became increasingly prominent as a conductor and in 1892 conducted his opera I Rantzau around Europe. Further successes included Amica (1905) and Isabeau (1911), alongside such failures as Le maschere (1901). In 1915 he experimented with writing for cinema in Rapsodia satanicawith Nino Oxilia. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters

04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 1 The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN , Chairman DEBORAH F. RUTTER , President CONCERT HALL Monday Evening, April 4, 2016, at 8:00 The Kennedy Center and the National Endowment for the Arts present The 2016 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert Honoring the 2016 National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters GARY BURTON WENDY OXENHORN PHAROAH SANDERS ARCHIE SHEPP Jason Moran is the Kennedy Center’s Artistic Director for Jazz. WPFW 89.3 FM is a media partner of Kennedy Center Jazz. Patrons are requested to turn off cell phones and other electronic devices during performances. The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not allowed in this auditorium. 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS 3/25/16 11:58 AM Page 2 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS TRIBUTE CONCERT Hosted by JASON MORAN, pianist and Kennedy Center artistic director for jazz With remarks from JANE CHU, chairman of the NEA DEBORAH F. RUTTER, president of the Kennedy Center THE 2016 NEA JAZZ MASTERS Performances by NEA JAZZ MASTERS: CHICK COREA, piano JIMMY HEATH, saxophone RANDY WESTON, piano SPECIAL GUESTS AMBROSE AKINMUSIRE, trumpeter LAKECIA BENJAMIN, saxophonist BILLY HARPER, saxophonist STEFON HARRIS, vibraphonist JUSTIN KAUFLIN, pianist RUDRESH MAHANTHAPPA, saxophonist PEDRITO MARTINEZ, percussionist JASON MORAN, pianist DAVID MURRAY, saxophonist LINDA OH, bassist KARRIEM RIGGINS, drummer and DJ ROSWELL RUDD, trombonist CATHERINE RUSSELL, vocalist 04-04 NEA Jazz Master Tribute_WPAS -

February 4, 2020 (XL:2) Lloyd Bacon: 42ND STREET (1933, 89M) the Version of This Goldenrod Handout Sent out in Our Monday Mailing, and the One Online, Has Hot Links

February 4, 2020 (XL:2) Lloyd Bacon: 42ND STREET (1933, 89m) The version of this Goldenrod Handout sent out in our Monday mailing, and the one online, has hot links. Spelling and Style—use of italics, quotation marks or nothing at all for titles, e.g.—follows the form of the sources. DIRECTOR Lloyd Bacon WRITING Rian James and James Seymour wrote the screenplay with contributions from Whitney Bolton, based on a novel by Bradford Ropes. PRODUCER Darryl F. Zanuck CINEMATOGRAPHY Sol Polito EDITING Thomas Pratt and Frank Ware DANCE ENSEMBLE DESIGN Busby Berkeley The film was nominated for Best Picture and Best Sound at the 1934 Academy Awards. In 1998, the National Film Preservation Board entered the film into the National Film Registry. CAST Warner Baxter...Julian Marsh Bebe Daniels...Dorothy Brock George Brent...Pat Denning Knuckles (1927), She Couldn't Say No (1930), A Notorious Ruby Keeler...Peggy Sawyer Affair (1930), Moby Dick (1930), Gold Dust Gertie (1931), Guy Kibbee...Abner Dillon Manhattan Parade (1931), Fireman, Save My Child Una Merkel...Lorraine Fleming (1932), 42nd Street (1933), Mary Stevens, M.D. (1933), Ginger Rogers...Ann Lowell Footlight Parade (1933), Devil Dogs of the Air (1935), Ned Sparks...Thomas Barry Gold Diggers of 1937 (1936), San Quentin (1937), Dick Powell...Billy Lawler Espionage Agent (1939), Knute Rockne All American Allen Jenkins...Mac Elroy (1940), Action, the North Atlantic (1943), The Sullivans Edward J. Nugent...Terry (1944), You Were Meant for Me (1948), Give My Regards Robert McWade...Jones to Broadway (1948), It Happens Every Spring (1949), The George E. -

JUKEBOX JAZZ by Ian Muldoon* ______

JUKEBOX JAZZ by Ian Muldoon* ____________________________________________________ n 1955 Bill Haley’s Rock Around the Clock was the first rock and roll record to become number one on the hit parade. It had made a stunning introduction in I the opening moments to a film called Blackboard Jungle. But at that time my favourite record was one by Lionel Hampton. I was not alone. Me and my three jazz loving friends couldn’t be bothered spending hard-earned cash on rock and roll records. Our quartet consisted of clarinet, drums, bass and vocal. Robert (nickname Orgy) was learning clarinet; Malcolm (Slim) was going to learn drums (which in due course he did under the guidance of Gordon LeCornu, a percussionist and drummer in the days when Sydney still had a thriving show scene); Dave (Bebop) loved the bass; and I was the vocalist a la Joe (Bebop) Lane. We were four of 120 RAAF apprentices undergoing three years boarding school training at Wagga Wagga RAAF Base from 1955-1957. Of course, we never performed together but we dreamt of doing so and luckily, dreaming was not contrary to RAAF regulations. Wearing an official RAAF beret in the style of Thelonious Monk or Dizzy Gillespie, however, was. Thelonious Monk wearing his beret the way Dave (Bebop) wore his… PHOTO CREDIT WILLIAM P GOTTLIEB _________________________________________________________ *Ian Muldoon has been a jazz enthusiast since, as a child, he heard his aunt play Fats Waller and Duke Ellington on the household piano. At around ten years of age he was given a windup record player and a modest supply of steel needles, on which he played his record collection, consisting of two 78s, one featuring Dizzy Gillespie and the other Fats Waller. -

JOAN CRAWFORD Early Life and Inspiration Joan Crawford Was Born Lucille Fay Lesueur on March 23, 1908, in San Antonio, Texas

JOAN CRAWFORD Early Life and Inspiration Joan Crawford was born Lucille Fay LeSueur on March 23, 1908, in San Antonio, Texas. Her biological father, Thomas E. LeSueur, left the family shortly after Lucille’s birth, leaving Anna Bell Johnson, her mother, behind to take care of the family. page 1 Lucille’s mother later married Henry J. Cassin, an opera house owner from Lawton, Oklahoma, which is where the family settled. Throughout her childhood there, Lucille frequently watched performances in her stepfather’s theater. Lucille, having grown up watching the many vaudeville acts perform at the theater, grew up wanting to pursue a dancing career. page 2 In 1917, Lucille’s family moved to Kansas City after her stepfather was accused of embezzlement. Cassin, a Catholic, sent Lucille to a Catholic girls’ school by the name of St. Agnes Academy. When her mother and stepfather divorced, she remained at the academy as a work student. It was there that she began dating and met a man named Ray Sterling, who inspired her to start working hard in school. page 3 In 1922, Lucille registered at Stephens College in Columbia, Missouri. However, she only attended the college for a few months before dropping out when she realized that she was not prepared enough for college. page 4 Early Career After her stint at Stephens, Lucille began dancing in various traveling choruses under the name Lucille LeSueur. While performing in Detroit, her talent was noticed by a producer named Jacob Shubert. Shubert gave her a spot in his 1924 Broadway show Innocent Eyes, in which she performed in the chorus line. -

The English Listing

THE CROSBY 78's ZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBAthe English listing Members may recall that we issued a THE questionnaire in 1990 seeking views and comments on what we should be providing in CROSBY BING. We are progressively attempting to fulfil 7 8 's these wishes and we now address one major ENGLISH request - a listing of the 78s issued in the UK. LISTING The first time this listing was issued in this form was in the ICC's 1974 booklet and this was updated in 1982in a publication issued by John Bassett's Crosby Collectors Society. The joint compilers were Jim Hayes, Colin Pugh and Bert Bishop. John has kindly given us permission to reproduce part of his publication in BING. This is a complete listing of very English-issued lO-inch and 12-inch 78 rpm shellac record featuring Sing Crosby. In all there are 601 discs on 10different labels. The sheet music used to illustrate some of the titles and the photos of the record labels have been p ro v id e d b y Don and Peter Haizeldon to whom we extend grateful thanks. NUMBERSITITLES LISTING OF ENGLISH 78"s ARIEl GRAND RECORD. THE 110-Inchl 4364 Susiannainon-Bing BRUNSWICK 112-inchl 1 0 5 Gems from "George White's Scandals", Parts 1 & 2 0 1 0 5 ditto 1 0 7 Lawd, you made the night too long/non-Bing 0 1 0 7 ditto 1 1 6 S I. L o u is blues/non-Bing _ 0 1 3 4 Pennies from heaven medley/Pennies from heaven THECROSBYCOLLECTORSSOCIETY BRUNSWICK 110-inchl 1 1 5 5 Just one more chance/Were you sincere? 0 1 6 0 8 Home on the range/The last round-up 0 1 1 5 5 ditto 0 1 6 1 5 Shadow waltz/I've got to sing a torch -

Boxoffice Barometer (March 6, 1961)

MARCH 6, 1961 IN TWO SECTIONS SECTION TWO Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents William Wyler’s production of “BEN-HUR” starring CHARLTON HESTON • JACK HAWKINS • Haya Harareet • Stephen Boyd • Hugh Griffith • Martha Scott • with Cathy O’Donnell • Sam Jaffe • Screen Play by Karl Tunberg • Music by Miklos Rozsa • Produced by Sam Zimbalist. M-G-M . EVEN GREATER IN Continuing its success story with current and coming attractions like these! ...and this is only the beginning! "GO NAKED IN THE WORLD” c ( 'KSX'i "THE Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents GINA LOLLOBRIGIDA • ANTHONY FRANCIOSA • ERNEST BORGNINE in An Areola Production “GO SPINSTER” • • — Metrocolor) NAKED IN THE WORLD” with Luana Patten Will Kuluva Philip Ober ( CinemaScope John Kellogg • Nancy R. Pollock • Tracey Roberts • Screen Play by Ranald Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer pre- MacDougall • Based on the Book by Tom T. Chamales • Directed by sents SHIRLEY MacLAINE Ranald MacDougall • Produced by Aaron Rosenberg. LAURENCE HARVEY JACK HAWKINS in A Julian Blaustein Production “SPINSTER" with Nobu McCarthy • Screen Play by Ben Maddow • Based on the Novel by Sylvia Ashton- Warner • Directed by Charles Walters. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents David O. Selznick's Production of Margaret Mitchell’s Story of the Old South "GONE WITH THE WIND” starring CLARK GABLE • VIVIEN LEIGH • LESLIE HOWARD • OLIVIA deHAVILLAND • A Selznick International Picture • Screen Play by Sidney Howard • Music by Max Steiner Directed by Victor Fleming Technicolor ’) "GORGO ( Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents “GORGO” star- ring Bill Travers • William Sylvester • Vincent "THE SECRET PARTNER” Winter • Bruce Seton • Joseph O'Conor • Martin Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents STEWART GRANGER Benson • Barry Keegan • Dervis Ward • Christopher HAYA HARAREET in “THE SECRET PARTNER” with Rhodes • Screen Play by John Loring and Daniel Bernard Lee • Screen Play by David Pursall and Jack Seddon Hyatt • Directed by Eugene Lourie • Executive Directed by Basil Dearden • Produced by Michael Relph.