A Graphetic Analysis of MS Glasow University Library Hunter 83. Mphil(R) Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proposal to Encode Four Latin Letters for Janalif — 2009-03-16 Page 1 of 8 in 1928 Jaalif Was Finally Reformed and Was in Active Usage for 12 Years (See Fig

Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set SC2/WG2 N3581 International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Proposal to encode four Latin letters for Jaalif Source: Karl Pentzlin, Ilya Yevlampiev (Илья Евлампиев) Status: Individual Contribution Action: For consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC Date: 2008-11-03, revised 2009-03-16 Revision history: The revision of 2009-03-16 takes into account the code points (U+A790/U+A791) devised by UTC #117 for the n with descender. Moreover, it takes into account the name "Latin capital/small letter yeru" for the letter initially proposed as "Latin capital i with right bowl / Latin small letter dotless i with right bowl", as proposed by Michael Everson and continued by the German comments to PDAM7. Also, some sorting considerations were added for the Latin yeru, and fig. 6 was updated. Additions for Janalif U+A790 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER N WITH DESCENDER → 04A2 cyrillic capital letter n with descender U+A791 LATIN SMALL LETTER N WITH DESCENDER U+A792 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER YERU → 042B cyrillic capital letter yeru → 042C cyrillic capital letter soft sign → 0184 latin capital letter tone six U+A793 LATIN SMALL LETTER YERU → 0131 latin small letter dotless i Properties: A790;LATIN CAPITAL LETTER N WITH DESCENDER;Lu;0;L;;;;;N;;;;A791; A791;LATIN SMALL LETTER N WITH DESCENDER;Ll;0;L;;;;;N;;;A790;;A790 A792;LATIN CAPITAL LETTER YERU;Lu;0;L;;;;;N;;;;A793; A793;LATIN SMALL LETTER YERU;Ll;0;L;;;;;N;;;A792;;A792 1. The Jaalif alphabet (fig. -

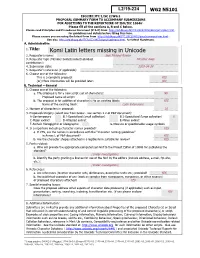

Komi Latin Letters Missing in Unicode 2

WG2 N5101 ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 PROPOSAL SUMMARY FORM TO ACCOMPANY SUBMISSIONS 1 FOR ADDITIONS TO THE REPERTOIRE OF ISO/IEC 10646TP PT Please fill all the sections A, B and C below. Please read Principles and Procedures Document (P & P) from HTU http://std.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/principles.html UTH for guidelines and details before filling this form. Please ensure you are using the latest Form from HTU http://std.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/summaryform.htmlUTH. See also HTU http://std.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/roadmaps.html UTH for latest Roadmaps. A. AdministratiVe 1. Title: Komi Latin letters missing in Unicode 2. Requester's name: Jack Michael Rueter 3. Requester type (Member body/Liaison/Individual Member body contribution): 4. Submission date: 2019-04-24 5. Requester's reference (if applicable): 6. Choose one of the following: This is a complete proposal: YES (or) More information will be provided later: NO B. Technical – General 1. Choose one of the following: a. This proposal is for a new script (set of characters): NO Proposed name of script: b. The proposal is for addition of character(s) to an existing block: YES Name of the existing block: Latin Extensions 2. Number of characters in proposal: 16 3. Proposed category (select one from below - see section 2.2 of P&P document): A-Contemporary B.1-Specialized (small collection) B.2-Specialized (large collection) X C-Major extinct D-Attested extinct E-Minor extinct F-Archaic Hieroglyphic or Ideographic G-Obscure or questionable usage symbols 4. -

Arabic Type Classification System

ARABIC TYPE CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM QUALITATIVE CLASSIFICATION OF HISTORIC ARABIC WRITING SCRIPTS IN THE CONTEMPORARY TYPOGRAPHIC CONTEXT BY DARIN ABU-SHAQRA | INCLUSIVE DESIGN | 2020 SUBMITTED TO OCAD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF DESIGN IN INCLUSIVE DESIGN TORONTO, ONTARIO, CANADA, 2020 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my sincere appreciation to both my primary advisor Richard Hunt, and secondary advisor Peter Coppin, your unlimited positivity, guidance and support was crucial to the comple- tion of this work. It was an absolute honour to have two geniuses in their fields as my advisors. Enriching my knowledge of typography and graphic design and looking through the lens of inclusive design and cognitive science of representation shaped a new respect for the cultural and experiential power of typography in me. My sincere gratitude goes to the talented calligraphers and graphic designers whom I have interviewed back in Jordan. Thank you, for your valuable time, and for allowing me to watch the world from different angles, and experiences. This project owes a lot to your motivation. My heartfelt thanks goes to my family - my late father Khalid, who, although is no longer with me, continues to inspire every step I have to take, my mother Nadia for being the symbol of strength and persistence, my siblings Yasmin, Omar, Ali and Abdullah for always believing in my dreams and doing whatever it takes to make them come true. A special thanks goes to the one who made those two years possible, Ra’ad thank you for being the definition of a life companion and a husband. -

Middle East-I 9 Modern and Liturgical Scripts

The Unicode® Standard Version 13.0 – Core Specification To learn about the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see http://www.unicode.org/versions/latest/. Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and the publisher was aware of a trade- mark claim, the designations have been printed with initial capital letters or in all capitals. Unicode and the Unicode Logo are registered trademarks of Unicode, Inc., in the United States and other countries. The authors and publisher have taken care in the preparation of this specification, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. © 2020 Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. This publication is protected by copyright, and permission must be obtained from the publisher prior to any prohibited reproduction. For information regarding permissions, inquire at http://www.unicode.org/reporting.html. For information about the Unicode terms of use, please see http://www.unicode.org/copyright.html. The Unicode Standard / the Unicode Consortium; edited by the Unicode Consortium. — Version 13.0. Includes index. ISBN 978-1-936213-26-9 (http://www.unicode.org/versions/Unicode13.0.0/) 1. -

Proposal to Encode Four Latin Letters for Janalif

Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Proposal to encode four Latin letters for Jaŋalif Source: Karl Pentzlin, Ilya Yevlampiev (Илья Евлампиев) Status: Individual Contribution Action: For consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC Date: 2008-11-03 Additions for Janalif U+A792 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER I WITH RIGHT BOWL = Janalif yeru → 042B cyrillic capital letter yeru → 042C cyrillic capital letter soft sign → 0185 latin small letter tone six U+A793 LATIN SMALL LETTER DOTLESS I WITH RIGHT BOWL U+A794 LATIN CAPITAL LETTER N WITH DESCENDER → 04A2 cyrillic capital letter n with descender U+A795 LATIN SMALL LETTER N WITH DESCENDER Properties: A792;LATIN CAPITAL LETTER I WITH RIGHT BOWL;Lu;0;L;;;;;N;;;;A793; A793;LATIN SMALL LETTER DOTLESS I WITH RIGHT BOWL;Ll;0;L;;;;;N;;;A792;;A792 A794;LATIN CAPITAL LETTER N WITH DESCENDER;Lu;0;L;;;;;N;;;;A795; A795;LATIN SMALL LETTER N WITH DESCENDER;Ll;0;L;;;;;N;;;A794;;A794 1. The Jaalif alphabet (fig. 3, 4) In 1908–1909 the Tatar poet Säğit Rämiev started to use the Latin alphabet in his own works. He offered the use of digraphs: ea for ä, eu for ü, eo for ö and ei for ı. But Arabists turned down his project. In the early 1920s Azerbaijanis invented their own Latin alphabet, but Tatarstan scholars set a little store to this project, preferring to reform the İske imlâ (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/iske_imla). The simplified İske imlâ, known as Yaña imlâ (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/yana_imla) was used from 1920–1927. -

Considerations in the Identification and Management of Variant Elements in Latin Script Tables for IDN Registration

Considerations in the identification and management of variant elements in Latin script tables for IDN registration Cary Karp Swedish Museum of Natural History This Support Brief was contributed to the ICANN VIP initiative by the host of its Latin script study, the Internet Infrastructure Foundation, with the support of the Swedish Museum of Natural History. The code points available for use in IDNs are all taken from the Unicode Character Code Charts. The Latin script is divided there into nine blocks. The one headed “Basic Latin” restates the ASCII repertoire and therefore includes the familiar letter-digit-hyphen (“LDH”) array to which TLD registries previously restricted all second-level domain names. The TLD labels, themselves, were further restricted to the letters in that repertoire. Latin letters other than the ‘a–z’ encoded in ASCII, as well as diacritically marked and otherwise decorated forms are presented in supplemental and extended Latin blocks, with further Latin letters in blocks under the heading “Phonetic Symbols”. Many of the marked letters can be represented with differing series of code points. Other letters that are intrinsically different and have different code points may share the same glyph. Protocol constraint renders the first of these situations tractable. Contextual restriction on the use of certain code points is necessary for the second. Basic concepts and considerations in the protocol and contextual management of these conditions are discussed below, with specific regard to the local collation of permissible IDN character repertoires and the identification of variant relationships among the listed characters. The rubric “Support Brief” indicates the intention of this text serving as a source document for the study group’s deliberations and report, without being a structured work in itself. -

Unibook Document

Title: Draft additional repertoire Amendment 2 (pdam2.1) to ISO/IEC 10646:2014 (4th edition) Date: 2014-10-05 L2/14-xxx WG2 N4637 Source: Michel Suignard, project editor Status: Project Editor's summary of the character repertoire addition as of October 2014 Action: For review by WG2 and UTC experts Distribution: WG2 and UTC Replaces: WG2 N4585 Status This document presents a summary of all characters that constitute the tentative repertoire of the amendment 2 to ISO/IEC 10646:2014, with code positions, representative glyphs and character names. In this document, the names and code positions are shown as currently approved by WG2 for the text of a future ballot. Manner of Presentation The character names and code points shown are the same for Unicode and ISO/IEC 10646, including annotations. Note to Reviewers UTC reviewers, please use this document as a summary of UTC review of pending ballots and proposals. Contents This document lists 11630 new characters (highlighted in yellow). The following list shows all 25 blocks (existing or new) to which characters are proposed to be added, or which have been affected by other changes documented here. 08A0-08FF Arabic Extended-A See document L2/013-130R L2/013-223 WG2 N4474 L2/014-105 N4589 N4592 N4597 0C80-0CFF Kannada See document: WG2 N4591 L2/014-153 0D00-0D7F Malayalam See document WG2 N4428 N4429 L2/013-063 L2/013-051 1C80-1C8F Cyrillic Extended-C See document WG2 N4607 L2/14-196 20A0-20CF Currency Symbols See document N4593 2300-23FF Miscellaneous Technical See document L2/14-009 N4535 -

Komi Latin Letters, Degrees of UNICODE Facilitation

dʑ Komi la?iꞩica, kəni UꞩIKOD-lən la?in ꞩ?pasjas oz t?rm?n?. Unaən najə? Komi Latin Letters, Degrees of UNICODE facilitation Perem vaƶ anbur das ꞩo?əd nem?aꞩ Old Permic Anbur fourteenth century Variation: (1) Descender (maintext), (2) Filled triangle below (title text) (3) Sloppy cedilla •<Lattin-Range Matches: Ⱬ ⱬ, Ƶ ƶ, ꞩ ꞩ, ʙ, Ə ə, ꞩ ꞩ, ᴣ, ɜ •Wrong pairs or glyphs: Ʒ ʒ •Outside the Latin range: Ь ь, Є є ꞩkolasa ꞩebəg?n ꞩ?paskud 1930 vojas?aꞩ 1930s school book presentation of alphabet The two literary languages Komi-Permyak and Komi-Zyrian have used numerous alphabets and orthographies from the 13th Комі лаԏін шыпасјас, кӧні УԊИКОД- century on. There are approximately six years of extensive publications in without recognizable texts. The typography is лӧн лаԏін шыпасјас оз тырмыны. considered inconsistently poor, and therefore it can be categorized Унаӧн најӧ? as a transitional alphabet. The term transitional alphabet, in turn, means that Unicode characters from mixed ranges can be used to Коми латин шыпасъяс, кӧні La?in ꞩ?pasjas, kodjas oz poⱬn? satisfy many of the missing letters. The poster will illustrate missing petkədl?n? Unikodən letters in the Latin range with discussion and derive the minimal УНИКОД-лӧн латин сьыпасъяс оз Latin letters with no representation alphabetical requirements for the documentation of these two Uralic тырмыны. Унаӧн найӧ? in Unicode regardless of range languages of Russia. Komi Latin Letters, Degrees of UNICODE facilitation vs transitional /tɕ/ /ɟ/ K??i kolə vəli giƶn?sə la?in ꞩ?pas uvti pasa ꞩ?pasjas -

Considerations in the Use of the Latin Script in Variant Internationalized Top-Level Domains

Considerations in the use of the Latin script in variant internationalized top-level domains Final report of the ICANN VIP Study Group for the Latin script Executive summary The study group examined all the characters in the Unicode Character Code Chart version 6.1.0 that are associated with the Latin script and valid under the IDNA2008 protocol. It identified several forms of “confusability” that might require careful consideration in the collation of a subset of the broader repertoire for local use. The resolution of such issues is, however, highly dependent on local orthographic conventions. These frequently treat the same characters in different manners. Strings that are confusingly similar in the context of one language may have no such connotations in another. Noting that the Latin script is used by a larger number of separate language communities than is any other single script, attempting to provide a comprehensive overview of the needs of all of them is an unrealistic endeavor. A summary attempt at doing so nonetheless would be culturally insensitive to communities that have yet to join the IDN discussion. The study group therefore finds no basis for the categorical treatment of any code point assigned to an element of the Latin script as being equivalent to any other such code point. Nor does it believe that any such basis exists beyond what is already incorporated in the IDNA2008 protocol. The ICANN TLD application process should not permit requests for multiple Latin strings under the premise that they are variants of each other. Careful scrutiny is required when evaluating proposed TLD labels for confusability but that does not make them variants in the focused sense of the VIP study. -

Unibook Document

Title: Draft additional repertoire for ISO/IEC 10646:2016 (5th ed.) Amendment 1.2 Date: 2016-09-29 L2/16-xxx WG2 N4770 Source: Michel Suignard, project editor Status: Project Editor's summary of the character repertoire addition as of September 29 2016 Action: For review by WG2 and UTC experts Distribution: WG2 and UTC Replaces: Status This document presents a summary of all characters that constitute the tentative new repertoire for ISO/IEC 10646 5th edition Amd1, with code positions, representative glyphs and character names. Manner of Presentation The character names and code points shown are the same for Unicode and ISO/IEC 10646, including annotations. Note to Reviewers UTC reviewers, please use this document as a summary of UTC review of pending ballots and proposals. WG2 Reviewers, please use this document as an aid during disposition of ballot comments. Contents This document lists 1178 characters. The following list shows all 29 blocks (existing or new) to which characters are proposed to be added, or which have been affected by other changes documented here. Some glyph updates are not shown in these code charts (U+13430 ę , and U+13431 Ě ), these will be done before the amendment goes through ballot. 07C0-07FF NKo See document L2/15-338 08A0-08FF Arabic Extended-A See document L2/16-056 0A00-0A7F Gurmukhi See document L2/16-209 0C80-0CFF Kannada See document L2/16-031 2B00-2BFF Miscellaneous Symbols and Arrows See document L2/16-064 L2/16-067 L2/16-080R 2E00-2E7F Supplemental Punctuation See document L2/15-327R L2/16-220 L2/16-235 -

Unibook Document

Title: Additional repertoire for ISO/IEC 10646:2017 (5th ed.) Amendment 2.2 Date: 2017-11-22 L2/17-1xx WG2 N4922 Source: Michel Suignard, project editor Status: Project Editor's summary of the character repertoire addition as of November 2017 Action: For review by WG2 and UTC experts Distribution: WG2 and UTC Replaces: Status This document presents a summary of all characters that constitute the tentative new repertoire for ISO/IEC 10646 5th edition Amd2, with code positions, representative glyphs and character names. Manner of Presentation The character names and code points shown are the same for Unicode and ISO/IEC 10646, including annotations. Note to Reviewers UTC reviewers, please use this document as a summary of UTC review of pending ballots and proposals. WG2 Reviewers, please use this document as an aid during disposition of ballot comments. Contents This document lists 6622 characters. The following list shows all 26 blocks (existing or new) to which characters are proposed to be added, or which have been affected by other changes documented here. 0C00-0C7F Telugu See document L2/17-218R WG2 N4860 0E80-0EFF Lao See document L2/17-106R WG2 N4861 1C90-1CBF Georgian Extended See document: L2/16-081 WG2 N4712 1CD0-1CFF Vedic Extensions See document: L2/16-117 WG2 N4820 2B00-2BFF Miscellaneous Symbols and Arrows See document L2/17-191 L2/17-151 WG2 N4863 N4864 2E00-2E7F Supplemental Punctuation See document WG2 N4902 4E00-9FEF CJK Unified Ideographs See document: N4830 N4831 N4832 A720-A7FF Latin Extended-D See document L2/17-076R2 -

Chembiodraw V14 User Guide

ChemBioDraw 14.0 User Guide ChemBioDraw 14.0 Table of Contents Recent Additions vi Chapter 1: Introduction 1 About this Guide 1 Chapter 2: Getting Started 4 About ChemBioDraw Tutorials 4 ChemBioDraw User Interface 4 Toolbars 5 Documents 6 Chapter 3: Page Layout 10 The Drawing Area 10 The Document Type 10 Printing 12 Saving Page Setup Settings 13 35mm Slide Boundary Guides 13 Viewing Drawings 14 Tables 16 Chapter 4: Preferences and Settings 20 Setting Preferences 20 Customizing Toolbars 23 Document and Object Settings 23 Customizing Hotkeys 33 Working with Color 35 Document Settings 38 Chapter 5: Shortcuts and Hotkeys 44 Atom Keys 44 Bond Hotkeys 45 Function Hotkeys 46 © Copyright 1998-2014 CambridgeSoft Corporation, a subsidiary of PerkinElmer, Inc. All rights reserved. i ChemBioDraw 14.0 Shortcuts 47 Nicknames 50 Chapter 6: Basic Drawings 52 Bonds 52 Atoms 57 Captions 58 Drawing Rings 67 Chains 69 Objects 71 Clean Up Structure 88 Checking Structures 89 Chemical Warnings 89 Chapter 7: BioDraw (Ultra feature only) 92 BioDraw Templates 92 Customizable Objects 95 Chapter 8: Drawing Biopolymers 101 Biopolymer Editor 102 Protecting Groups 103 Pasting Sequences 104 Expanding Sequences 106 Contracting Labels 106 Modifying Sequence Residues 107 Merging Sidechains with Residue 107 Hybrid Biopolymers 110 IUPAC Codes 111 Disulfide Bridges 115 Lactam Bridges 116 Chapter 9: Advanced Drawing Techniques 118 Coloring Objects 118 © Copyright 1998-2014 CambridgeSoft Corporation, a subsidiary of PerkinElmer, Inc. All rights reserved. ii ChemBioDraw 14.0