Stressing Knowledge Stressing Knowledge Closed-Ness and Organisational Under Pressure Acquisition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WORLD AVIATION Yearbook 2013 EUROPE

WORLD AVIATION Yearbook 2013 EUROPE 1 PROFILES W ESTERN EUROPE TOP 10 AIRLINES SOURCE: CAPA - CENTRE FOR AVIATION AND INNOVATA | WEEK startinG 31-MAR-2013 R ANKING CARRIER NAME SEATS Lufthansa 1 Lufthansa 1,739,886 Ryanair 2 Ryanair 1,604,799 Air France 3 Air France 1,329,819 easyJet Britis 4 easyJet 1,200,528 Airways 5 British Airways 1,025,222 SAS 6 SAS 703,817 airberlin KLM Royal 7 airberlin 609,008 Dutch Airlines 8 KLM Royal Dutch Airlines 571,584 Iberia 9 Iberia 534,125 Other Western 10 Norwegian Air Shuttle 494,828 W ESTERN EUROPE TOP 10 AIRPORTS SOURCE: CAPA - CENTRE FOR AVIATION AND INNOVATA | WEEK startinG 31-MAR-2013 Europe R ANKING CARRIER NAME SEATS 1 London Heathrow Airport 1,774,606 2 Paris Charles De Gaulle Airport 1,421,231 Outlook 3 Frankfurt Airport 1,394,143 4 Amsterdam Airport Schiphol 1,052,624 5 Madrid Barajas Airport 1,016,791 HE EUROPEAN AIRLINE MARKET 6 Munich Airport 1,007,000 HAS A NUMBER OF DIVIDING LINES. 7 Rome Fiumicino Airport 812,178 There is little growth on routes within the 8 Barcelona El Prat Airport 768,004 continent, but steady growth on long-haul. MostT of the growth within Europe goes to low-cost 9 Paris Orly Field 683,097 carriers, while the major legacy groups restructure 10 London Gatwick Airport 622,909 their short/medium-haul activities. The big Western countries see little or negative traffic growth, while the East enjoys a growth spurt ... ... On the other hand, the big Western airline groups continue to lead consolidation, while many in the East struggle to survive. -

As Things Should Be but Never Are

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Summer 8-2-2012 As Things Should Be but Never Are Justin Burnell University of New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Burnell, Justin, "As Things Should Be but Never Are" (2012). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 1534. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/1534 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. As Things Should Be but Never Are A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of A Master of Fine Arts in Film, Theater, and Communication Arts Concentration in Creative Writing - Fiction by Justin Burnell BA University of New Orleans 2007 August 2012 Acknowledgments I cannot express my full gratitude to my thesis committee: Barb Johnson, Joseph Boyden, and Dr. -

ANSV Italy Accident Boeing MD-87 SE-DMA and Cessna D-IEVX

AGENZIA NAZIONALE PER LA SICUREZZA DEL VOLO (istituita con decreto legislativo 25 febbraio 1999, n. 66) Via A. Benigni, 53 - 00156 Roma - Italia tel. +39 0682078219 - 0682078200 - fax +39 068273672 FINAL REPORT (As approved by ANSV Board on the 20th of January 2004) ACCIDENT INVOLVED AIRCRAFT BOEING MD-87, registration SE-DMA and CESSNA 525-A, registration D-IEVX Milano Linate airport October 8, 2001 N. A/1/04 INDEX INDEX . I PURPOSE OF THE TECHNICAL INVESTIGATION. VII SYNOPSIS . VIII GLOSSARY. IX CHAPTER I - GENERAL INFORMATION . 1 1. GENERAL INFORMATION . 1 1.1. HISTORY OF THE EVENT . 1 1.1.1. Aircraft involved. 1 1.1.2. ATC situation . 4 1.1.3. Aircraft movement on the ground . 4 1.1.4. Collision. 7 1.1.5. MD-87 impact with the baggage building . 8 1.1.6. First alert . 9 1.2. INJURIES TO PERSONS . 11 1.3. DAMAGE TO AIRCRAFT . 11 1.3.1. Boeing MD-87 . 11 1.3.2. Cessna 525-A . 12 1.4. OTHER DAMAGE . 13 1.5. PERSONNEL INFORMATION . 13 1.5.1. Pilots . 13 1.5.1.1. Pilots of the Boeing MD-87 . 13 1.5.1.2. Pilots of the Cessna 525-A. 14 1.5.1.3. The status of the Milano Linate to Paris Le Bourget flight . 16 1.5.2. Cabin crew . 17 1.5.3. Air Traffic Controllers. 17 1.5.4. Fire brigade personnel . 20 1.5.5. Airport Civil Aviation Authority personnel (UCT-DCA) . 21 1.5.6. SEA station manager . 21 1.5.7. -

Cost-Benefit Analysis of Two Similar Warm Standby Aircraft System

International Journal of Recent Advances in Engineering & Technology (IJRAET) ________________________________________________________________________________________________ Cost-Benefit Analysis of Two Similar Warm Standby aircraft system subject to failure due to bad weather conditions and air traffic congestion; fog and wind deadliest air disasters caused by miscommunication Ashok Kumar Saini BLJS COLLEGE, TOSHAM (BHIWANI) HARYANA INDIA Email : [email protected] on human life. Here’s are the worst air crashes caused Abstract : In the technological world of modern air travel, there’s a certain irony in the fact that the majority of by miscommunication. aviation disasters are caused by human error. And one of Avianca Flight 52 (1990) the most common forms of error is miscommunication. Even if just one person makes a mistake, the repercussions can be catastrophic. In this paper we have taken failure due to bad weather conditions and air traffic congestion; fog and wind deadliest air disasters caused by miscommunication. When the main unit fails then warm standby system becomes operative. Failure due to fog and wind cannot occur simultaneously in both the units and after failure the unit undergoes Type-I or Type-II or Type-III or Type IV repair facility immediately. Applying the regenerative point technique with renewal process theory the various reliability parameters MTSF, Availability, Busy period, Benefit-Function analysis have been evaluated. On January 25, 1990, Avianca Flight 52 was carrying Keywords: Warm Standby, failure due to bad weather 149 passengers from Bogotá, Colombia to New York. conditions and air traffic congestion; fog and wind However, because of bad weather conditions and air deadliest air disasters caused by miscommunication, first come first serve, MTSF, Availability, Busy period, traffic congestion, the Boeing 707 was forced into a Expected number of visits by the repairman , Benefit - holding pattern off the coast near New York. -

Milan Linate (LIN) J Ownership and Organisational Structure the Airport

Competition between Airports and the Application of Sfare Aid Rules Volume H ~ Country Reports Italy Milan Linate (LIN) J Ownership and organisational structure The airport is part of Gruppo SEA (Milan Airports). Ownership is 14.6% local government and 84.6% City of Milan. Other shareholders hold the remaining 0.8%. Privatisation (partial) was scheduled for the end of 2001 but was stopped after the events of 11th September. Now the proposed date is October 2002 but this has still to be finalised. Only 30% of the shareholding will be moved into the private sector with no shareholder having more than 5%. There are no legislative changes required. The provision of airport services is shared between ENAV (ATC), Italian police (police), SEA (security), ATA and SEA Handling (passenger and ramp handling), Dufntal (duty-free) and SEA Parking (car parking). There are no current environmental issues but, in the future, there is a possible night ban and charges imposed according to aircraft noise. 2 Type ofairpo Milan Linate is a city-centre (almost) airport that serves mainly the scheduled domestic and international market with a growing low-cost airline presence (Buzz, Go). There is very little charter and cargo traffic but some General Aviation. The airport is subject to traffic distribution rules imposed by the Italian government with the aim of 'encouraging' airlines to move to Malpensa. Traffic Data (2000) Domestic fíghts Scheduled Charter Total Terminal Passengers (arrivals) 2 103 341 _ 2 103 341 Terminal Passengers (departures) 2 084 008 -

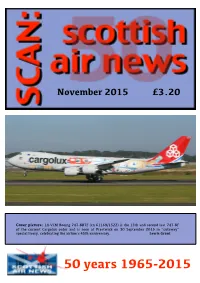

Scan 2015-11

SCrjtrjrjj-j 5 j jf ne v/5 November 2015!!!£3.20 ■y) Cover picture: LX-VCM Boeing 747-8R7F (cn 61169/1522) is the 13th and second last 747-8F of the current Cargolux order and is seen at Prestwick on 30 September 2015 in “cutaway” special livery, celebrating the airline’s 45th anniversary.!! ! Lewis Grant 50 years 1965-2015 NO 430 Scottish Air News N995M Bombardier BD700-1A10 Global Express (cn 9322) on ‘Charlie’ with N526EE Gulfstream 4 (cn 1304) both Dunhill Golf Tournament visitors at Dundee on 29 September 2015.!! ! John Chalmers Qli "" ill'' ' ini'i^iV"1 wMjrii"1 f " BM — — , - ••■v.. „s, "• . •' '..if— ... aSraSw \ (VP-BRV) Boeing 737-528 cn 25227/2018, ex Yamal Ailines and Air France, has been positioned for use as a restaurant at a Go Kart Centre in Montrose Avenue Hillington Industrial Estate, Glasgow, and is seen soon after arrival from Kemble store on 14 October 2015.!!! Peter McCann - • i u o a • • « « « h „ smm L ?«* . i < < bB ZE708 BAe146 C.3 (cn 2211) is seen at Prestwick on 30 September 2015. Operated by 32 Sqn, the 5rvY aircraft was initially used in Afghanistan, and is• •• formerly OO-TAY of TNT Airways and one time Edinburgh regular.!!!!!!!!!! Lewis Grant ^ -- V amm Scottish Air News NO 431 scottish air news November 2015 Volume 50 MANAGING EDITOR Paul Wiggins E Mail : [email protected] Editorial Address : Grinsdale House, Grinsdale, Carlisle, CA5 6DS NEWS SECTION RESIDENTS SECTION Jim Fulton Alistair Ness E Mail : [email protected] E Mail : [email protected] MILITARY SECTION WEBSITE UPDATES AND QUERIES Vacancy, copy to Paul Wiggins meantime Scott Jamieson E Mail : [email protected] AIRFIELDS SCANNED SUB-EDITORS Aberdeen Ian Grierson Edinburgh Sandy Benzies / Alistair Ness Dundee / Perth Tim Gulson Glasgow Alan Reid Highlands/Islands Alan Nightingale Inverness Stephen Lane Prestwick Alan McKnight PHOTO SUBMISSIONS Please send photos via e-mail to Lorence Fizia , e-mail address is scanphotos1gmail.com Photos should be high quality JPEGs, uncompressed straight from the camera, and in colour. -

Sick Puppies Connect Her Own on Connect, with More and That’S Rounded Us out When We on Saturday, September 7, the Other, Their Own Psyches—And Vate New Ones

K k AUGUST 2013 KWOW HALL NOTES g VOL. 25 #8 H WOWHALL.ORGk release of Tri-Polar (nearly half a up by adding Orange County, million units to date and over 2 California-bred drummer Mark million single sold) and its slew of Goodwin, who they met through a radio hits—the #1 Rock track classified ad following their move “You’re Going Down”, the Top to LA in 2006. Soon after signing Five Modern Rock/Active Rock to Paul Palmer’s indie label through hits “Odd One” and “Riptide” and Virgin Records, a fortuitous video the cross-format anthemic smash pairing with a friend led Sick “Maybe”. Now Connect (out July Puppies to online fame with the 16, 2013), with its melding of song “All The Same” (AKA the room-filling rockers and edgy yet Free Hugs video), which earned an poignant lyrics, is poised to be the astonishing 75-million-plus views Puppies’ best-selling record yet. worldwide, and led to appearances Produced, as was Tri-Polar, by on Oprah, 60 Minutes, CNN, the Rock Mafia production team Good Morning America, and The of Tim James and Antonina Tonight Show with Jay Leno. Armato, Connect also took guid- Drummer Goodwin notes: ance from another, very pure “We’re a career band. We want to source: the trio’s legions of fans. build and take the time to make With face-to-face and online inter- things right. The first time we ever action with Sick Puppies World jammed it was a massive wall of Crew, the band listened when fol- sound; amazing for a trio. -

Airports Council International

AIRPORTS COUNCIL INTERNATIONAL AIRPORTS COUNCIL INTERNATIONAL Celebrating 20 Years – 1991-2011 CELEBRATING 20 YEARS – 1991-2011 20YEARS Airports Council International 1991-2011 CAH-420x210.pdf 1 2011-5-24 16:28:50 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K RZ_1_inserat_1.indd 1 25.05.11 11:22 20YEARS Airports Council International 1991-2011 Airports Council International CELEBRATING 20 YEARS – 1991-2011 Published by International Systems and Communications Limited (ISC) in conjunction with Airports Council International (ACI). Copyright © 2011. The entire content of this publication is protected by copyright, full details of which are available from the publisher. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in retrieval systems or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISC ACI World Park Place 800 rue du Square Victoria 12 Lawn Lane Suite 1810, PO Box 302 London SW8 1UD Montreal England Quebec H4Z 1G8 Canada Telephone: + 44 20 7091 1188 Facsimile: + 44 20 7091 1198 Telephone: +1 514 373 1200 E-mail: [email protected] Facsimile: +1 514 373 1201 Website: www.isyscom.com E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.aci.aero RZ_1_inserat_1.indd 1 25.05.11 11:22 78654•SNC-AP-Airport:Ap-Airport-V2 2/05/11 18:26 Page 1 Contents ACI: Mission, Objectives, Structure 6 ACI Africa 145 Message from the Chair of the ACI World ACI Africa Intensifies its Efforts 148 Governing Board 8 By Monhla Hlahla By Max Moore-Wilton Cairo Redevelops -

Air Traffic Delay in Europe

EUROCONTROL Trends in Air Traffic l Volume 2 A Matter of Time: Air Traffic Delay in Europe Acknowledgements The idea for this study came from Tim Guest, Manager of the EUROCONTROL Central Office for Delay Analysis, who expressed concerns that outside of a few specialists in Air Traffic Management, there was a relatively poor understan- ding of air traffic delay. With the cooperation of the EDAG, the supervising group for CODA, and particularly with the help of the Association of European Airlines (AEA) and the International Air Carrier Association (IACA), this document has been developed to help explain delay and to eliminate misunderstandings and misconceptions. Tim Guest was the principal author of this study and the force behind its production; it was his encyclopedic knowledge of the sub- ject that we have sought to capture in this volume. Bo Redeborn, EUROCONTROL Director of ATM Strategies approved the further development of this series of studies into air traffic market sectors with the objective of increasing the depth of knowledge. I am grateful to him for his support and encouragement. Thanks go to the CODA team, Tony Leggat, Catherine Yven and Yves De Wandeler for their considerable contributions and support. We are grateful also to EUROCONTROL’s External and Public Relations Unit for their help in the design and publication of the document. Thanks go also to a number of people who reviewed the document, suggested changes and helped in the proof reading. Notable among these were Terry Symmans of the EUROCONTROL Experimental Centre and Sue Lockey from AEA. Any remaining errors are our own. -

English Skills Answers Contents

English Skills Answers Contents Reading Rescue 4 Writing 50 Activities 5 Language 51 Cloze 6 Grammar 7 Reading Elephants 52 Writing 8 Activities 53 Language 9 Writing 54 Grammar 55 Reading UFOs 10 Writing 56 Activities 11 Language 57 Cloze 12 Grammar 13 Reading The Bears 58 Writing 14 Activities 59 Language 15 Cloze 60 Grammar 61 Reading The Crocodile – 16 Writing 62 An Endangered Species Language 63 Activities 17 Cloze 18 Reading Apollo 13 64 Published by Collins Grammar 19 Activities 65 An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Cloze 66 77–85 Fulham Palace Road Writing 20 Language 21 Grammar 67 Hammersmith Writing 68 London Plant Survival 22 Grammar 69 W6 8JB Reading Activities 23 Cloze 24 Reading The Battle of Marathon 70 Grammar 25 Activities 71 Browse the complete Collins catalogue at Writing 26 Cloze 72 www.collinseducation.com Language 27 Grammar 73 Writing 74 Reading The Grand Canyon 28 Language 75 Activities 29 © HarperCollinsPublishers Limited 2011, on behalf of the author Cloze 30 Reading An Intrepid Traveller 76 Activities 77 First published in 2006 by Folens Limited. Grammar 31 Writing 32 Writing 78 Grammar 79 ISBN-13: 978-0-00-743723-8 Language 33 Writing 80 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval Reading The Robin 34 Language 81 system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, Activities 35 recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Publisher or a licence Phonics 36 Reading The Pharos of Alexandria 82 permitting restricted copying in the United Kingdom issued by the Copyright Licensing Grammar 37 Activities 83 Agency Ltd, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP. -

Chapter 3 Runway Incursions

POLITECNICO DI TORINO Master’s Degree in Aerospace Engineering Master’s Degree Thesis Analysis of an Aeronautical Database and Correlation with Single Pilot Operations Supervisors Candidate Prof. Giorgio GUGLIERI Luigi RUSSO S266152 Dr. Beatrice CONTI Dr. Teodor ROCI Academic Year 2020/2021 Abstract The aim of the present master thesis is to conduct an analysis of the prob- lem of Runaway Incursions as a compromising element for the introduction of Single Pilot Operations (SiPO), also posing a major threat to flight safety around the world, especially in small airports. All the topics are going to be contextualized in the modern COVID-19 situation. Most of the data used for statistical purposes have been provided by ENAC through the eE-MOR database. Single Pilot Operations and Reduced Crew Operations are considered, by emphasizing the advantages and disadvantages and by describing the opposite reasons towards or against SiPO. Different solutions that might be applied in the following years in order to mitigate risks and increase safety are also going to be shown. Finally, the thesis analyses as a case study a relevant aviation incident in Italy, the 2001 Milano Linate Airport disaster, which caused the death of 118 people. The causes of this accident are described, with big emphasis on how the disaster could have been avoided and possible countermeasures. i Acknowledgements A Paolo, Margherita e Gennaro, colonne portanti della mia vita. A Paola per aver condiviso con me gioie e difficoltà di questo percorso. A parenti e amici che sono stati al mio fianco in questi anni. Grazie. ii Table of Contents List of Tables vi List of Figures vii Acronyms xi 1 Introduction 1 2 Towards Single Pilot Operations 4 2.1 State of art...........................4 2.1.1 CRM Crew Resource Management..........4 2.1.2 MCC Multi Crew Coordination............5 2.2 Pilot Incapacitation.......................7 2.3 Future trend.......................... -

The Temporal Configuration of European Airline

THE TEMPORAL CONFIGURATION OF EUROPEAN AIRLINE NETWORKS Guillaume Burghouwt Utrecht University, Faculty of Geographical Sciences PO Box 80115, 3058 TC Utrecht, the Netherlands Tel: 030 2531399, Fax: 030 2532037 g.burghouwt_geog.uu.nl Jaap de Wit University of Amsterdam, SEO Amsterdam Economics/Amsterdam Aviation Economics 1018 WB Amsterdam, the Netherlands i_dewit(_fee.uva.nl Abstract The deregulation of US axfiation in 1978 resulted in the reconiiguration of airline networks into hub-and-spoke systems, spatially concentrated around a small number of central airports or 'hubs' through which an airline operates a number of daily waves of flights. A hub-and-spoke network requires a concentration of traffic in both space and time. In contrast to the U.S. airlines, European airlines had entered the phase of spatial network concentration long before deregulation. Bilateral negotiation of traffic fights between governments forced European airlines to focus their networks spatially on small number of 'national' airports. In general, these star-shaped networks were not coordinated in time. Transfer opportunities at central airports were mostly created 'by accident'. With the deregulation of the EU air transport market from 1988 on, a second phase of airline network concentration started. European airlines concentrated their networks in time by adopting or intensifying wave-system structures in their flight schedules. Temporal concentration may increase the competitive position of the network in a deregulated market because of certain cost and demand advantages. This paper investigates to what extent a temporal concentration trend can be observed in the European aviation network after deregulation. We will analyze the presence and configuration of wave-system structures at European airline hubs as well as the resulting transfer opportunities.