Shakespeare's Heroines in American Musical Theater

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadway Starts to Rock: Musical Theater Orchestrations and Character, 1968-1975 By

Broadway Starts to Rock: Musical Theater Orchestrations and Character, 1968-1975 By Elizabeth Sallinger M.M., Duquesne University, 2010 B.A., Pennsylvania State University, 2008 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Musicology and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Chair: Paul R. Laird Roberta Freund Schwartz Bryan Kip Haaheim Colin Roust Leslie Bennett Date Defended: 5 December 2016 ii The dissertation committee for Elizabeth Sallinger certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Broadway Starts to Rock: Musical Theater Orchestrations and Character, 1968-1975 Chair: Paul R. Laird Date Approved: 5 December 2016 iii Abstract In 1968, the sound of the Broadway pit was forever changed with the rock ensemble that accompanied Hair. The musical backdrop for the show was appropriate for the countercultural subject matter, taking into account the popular genres of the time that were connected with such figures, and marrying them to other musical styles to help support the individual characters. Though popular styles had long been part of Broadway scores, it took more than a decade for rock to become a major influence in the commercial theater. The associations an audience had with rock music outside of a theater affected perception of the plot and characters in new ways and allowed for shows to be marketed toward younger demographics, expanding the audience base. Other shows contemporary to Hair began to include rock music and approaches as well; composers and orchestrators incorporated instruments such as electric guitar, bass, and synthesizer, amplification in the pit, and backup singers as components of their scores. -

Preface to the First Edition 1

NOTES Preface to the First Edition 1. The Rodgers and Hammerstein Song Book (New York: Simon & Schuster and Williamson Music, 1956); Six Plays by Rodgers and Hammerstein (New York: Modern Library Association, 1959). 2. Like other Broadway-loving families, especially those residing on the west side of the coun- try, it took the release of the West Side Story movie with Natalie Wood for us to become fully cognizant of this show. 3. “The World of Stephen Sondheim,” interview, “Previn and the Pittsburgh,” channel 26 tele- vision broadcast, March 13, 1977. 4. A chronological survey of Broadway texts from the 1950s to the 1980s might include the fol- lowing: Cecil Smith, Musical Comedy in America; Lehman Engel, The American Musical Theater; David Ewen, New Complete Book of the American Musical Theatre; Ethan Mordden, Better Foot Forward; Abe Laufe, Broadway’s Greatest Musicals (New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1977); Martin Gottfried, Broadway Musicals; Stanley Green, The World of Musical Comedy; Richard Kislan, The Musical (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1980); Gerald Bordman, American Musical Comedy, American Musical Theatre, American Musical Revue, and American Operetta; Alan Jay Lerner, The Musical Theatre: A Celebration; and Gerald Mast, Can’t Help Singin.’ 5. See Gerald Bordman, American Musical Comedy, American Musical Revue, and American Oper- etta, and Lehman Engel, The American Musical Theater. 6. Miles Kreuger, “Show Boat”: The Story of a Classic American Musical; Hollis Alpert, The Life and Times of “Porgy and Bess.” The literature on Porgy and Bess contains a particularly impres- sive collection of worthwhile analytical and historical essays by Richard Crawford, Charles Hamm, Wayne Shirley, and Lawrence Starr (see the Selected Bibliography). -

Playbill: 42Nd Street at the Umbrella

42 ND STREET INAUGURAL SEASON This production made possible by the generosity of Cast and Crew Members from The Umbrella Stage’s Seasons 1-11 This 2019-2020 season is made possible by the generosity of Kate and Mark Reid in memory of Kate’s mother, Micheline Sakharoff 40 STOW STREET, CONCORD, MA | TheUmbrellaStage.org Proud sponsor of THE UMBRELLA Community Arts Center Best wishes for a successful 2019-2020 Performing Arts Season! ADAGE CAPITAL MANAGEMENT, LP 200 CLARENDON STREET 52nd FLOOR BOSTON, MASSACHUSETTS 02116 PHONE: 617.867.2800 adagecapital.com THE UMBRELLA STAGE COMPANY PRESENTS Music by Lyrics by HARRY WARREN AL DUBIN Book by MICHAEL STEWART & MARK BRAMBLE Based on the Novel by BRADFORD ROPES Original Direction and Dances by GOWER CHAMPION Originally Produced on Broadway by DAVID MERRICK Directed by Brian Boruta Music Direction by James Murphy Musical Restaging and New Choreography by Lara Finn Banister Scenic Design by Lighting Design by Sound Design by Benjamin D. Rush SeifAllah Sallotto-Cristobal Elizabeth Havenor Costume Design by Properties Design by Stage Managed by Brian Simons Sarajane Morse Mullins Michael T. Lacey 42ND STREET is presented by arrangement with Funded in part by the Tams-Witmark, A Concord Theatricals Company www.tamswitmark.com The use of all songs is by arrangement with Warner Bros., the owner of music publishers’ rights Dear Friends, Welcome to The Umbrella, where there’s so much that’s exciting and new to share with you! Of course, we are beyond thrilled to introduce you to our two newly constructed theaters – part of a massive, multiyear renovation and expansion campaign that saw the transformation of every aspect of our Arts center. -

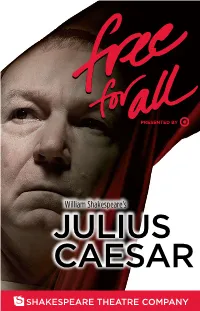

Julius Caesar

PRESENTED BY William Shakespeare's JULIUS CAESAR SHAKESPEARE THEATRE COMPANY Dear Friend, "i thank you for your pains and courtesy". Table of Contents I hope you will enjoy one of Julius Caesar, act 2, scene 2 Letter from Michael Kahn 3 Shakespeare’s most politically Out of the Past charged pieces, uniquely suited by Akiva Fox 4 to Washington, D.C., audiences. Synopsis 7 Julius Caesar reaches into the ThE 2011 ShakESPEaRE ThEaTRE ComPaNY About the Playwright 9 heart of Roman history to explore not only the consequences of Title Page 11 FREE FoR all iS PRESENTED BY conspiracy but also the complications of political Cast 12 ambition. David Muse’s original 2008 production Cast Biographies 13 was called “majestic” by the Washington Times and hailed as “electrifying” by DC Theatre Review. Direction and Design Biographies 21 I am pleased to make this wonderful production available to the Washington community for free, Shakespeare: with the generous support of sponsors like Target Caesar of Playwrights? 26 and donors like the Friends of Free For All. Shakespeare Theatre Company There could be no greater gift on the eve of this Board of Trustees 6 anniversary season than to celebrate its opening Shakespeare Theatre with you—friends new and old. I hope you will Company 24 return during the 2011-2012 Season to experience some of the exciting events we have in store. This Friends of Free For All 28 Ad Space season is sure to bring many memorable moments For the Shakespeare to STC stages, from the classic works of Regnard, Theatre Company 30 O’Neill and Goldoni to Shakespeare’s Much Ado Staff 32 About Nothing, The Two Gentlemen of Verona Happenings 33 and The Merry Wives of Windsor. -

Park Avenue Armory Announces Full Casting for Macbeth

PARK AVENUE ARMORY ANNOUNCES FULL CASTING FOR MACBETH Directed by Rob Ashford and Kenneth Branagh, Site-Specific Staging Begins Performances May 31, 2014 Commissioned and produced by Park Avenue Armory and Manchester International Festival New York, NY – May 12, 2014 – Park Avenue Armory announced today full casting for the U.S. premiere of Rob Ashford and Kenneth Branagh’s staging of Macbeth, May 31-June 22, 2014. The production transforms the Armory and its 55,000-square-foot drill hall, taking advantage of the building’s unique spaces and military history to bring to life one of Shakespeare’s most powerful tragedies in an intensely physical, fast-paced production that places the audience directly on the frontlines of battle. The audience will be drawn into the blood, sweat, and elements of nature as the action unfurls across a traverse stage, with heaven beckoning at one end and hell looming at the other. Kenneth Branagh is joined by Alex Kingston as the once great leader and his adored wife—marking the New York stage debuts for both actors. The critically acclaimed production was originally mounted in Manchester in July 2013, and is being re-imagined for the Armory’s dramatic spaces. The majority of the cast will reprise their roles, with the additions of Richard Coyle (Proof, Donmar Warehouse) as Macduff, Scarlett Strallen (Merry Wives of Windsor, Royal Shakespeare Company) as Lady Macduff; Tom Godwin (The Taming of the Shrew, Globe) as Porter; Edward Harrison (Henry V, West End) as Lennox; Dylan Clark Marshall (Revolutionary Road); Zachary Spicer (Wit, Manhattan Theatre Club); and Kate Tydman (Kiss Me, Kate, Old Vic) as a Swing. -

The Man Who Knew Infinity

PRESENTS THE MAN WHO KNEW INFINITY An EDWARD R. PRESSMAN/ANIMUS FILMS production in association with CAYENNE PEPPER PRODUCTIONS, XEITGEIST ENTERTAINMENT GROUP, MARCYS HOLDINGS A film by Matthew Brown Starring Dev Patel, Jeremy Irons introducing Devika Bhise with Stephen Fry and Toby Jones FILM FESTIVALS 2015 TORONTO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL 108 MINS / UK / COLOUR / 2015 / ENGLISH Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith Star PR Tel: 416-488-4436 1352 Dundas St. West Fax: 416-488-8438 Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1Y2 E-mail: [email protected] Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com @MongrelMedia MongrelMedia SHORT SYNOPSIS Written and directed by Matthew Brown, The Man Who Knew Infinity is the true story of friendship that forever changed mathematics. In 1913, Srinivasa Ramanujan (Dev Patel), a self-taught Indian mathematics genius, traveled to Trinity College, Cambridge, where over the course of five years, forged a bond with his mentor, the brilliant and eccentric professor, G.H. Hardy (Jeremy Irons), and fought against prejudice to reveal his mathematic genius to the world. The film also stars Devika Bhise, Stephen Fry and Toby Jones. This is Ramanujan’s story as seen through Hardy’s eyes. LONG SYNOPSIS Colonial India, 1913. Srinavasa Ramanujan (Dev Patel) is a 25-year-old shipping clerk and self-taught genius, who failed out of college due to his near-obsessive solitary study of mathematics. Determined to pursue his passion despite rejection and derision from his peers, Ramanujan writes a letter to G. H. Hardy (Jeremy Irons), an eminent British mathematics professor at Trinity College, Cambridge. -

The Concept of Otherness in Shakespearean Film Rathiga

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ScholarBank@NUS THE CONCEPT OF OTHERNESS IN SHAKESPEAREAN FILM RATHIGA VEERAYAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2003 THE CONCEPT OF OTHERNESS IN SHAKESPEAREAN FILM RATHIGA VEERAYAN (B.A. (HONS), NUS) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2003 i Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Dr. Yong Li Lan to whom I am greatly indebted. Her incisive comments constantly challenged me to re-evaluate and rethink my arguments at crucial points of the writing process and I deeply appreciate her guidance and generous willingness to share her extensive knowledge on Shakespearean film with me. I would also like to take this opportunity to thank my family for their unwavering conviction in me and for the infinite love and support they have given me throughout the years. ii CONTENTS 1. Introduction: The Mirror has Two Faces: Self and Other in Shakespearean Film 1 2. Shakespeare Through the Looking Glass: The Otherness of the Medium in Shakespearean Film. 17 3. Shakespeare Our Contemporary: The Otherness of the Past in Shakespearean Film 35 4. Looking for Shakespeare: Self-reflexivity in Shakespearean Film 93 5. The Lady Doth Protest Too Much Methinks: Woman as Other in Shakespearean Film 116 6. Conclusion: Our Revels Now Are Ended 140 List of Works Cited 148 List of Films Cited 155 List of Television Programmes Cited 160 iii Summary Using Lacanian theory and more specifically Lacan’s essay on ‘The Mirror Stage’ as a foundation for thinking about the cultural project of reproducing and popularizing Shakespeare, the main purpose of this thesis is to consider various definitions of otherness and examine how they can be applied to Shakespearean film. -

©2019 Disney Enterprises, Inc. All Rights Reserved. DISNEY Tony

©2019 Disney Enterprises, Inc. All Rights Reserved. DISNEY Tony . F. MURRAY ABRAHAM presents Joe . .ARTURO CASTRO Doctor . KEN JEONG Foreman . .CURTIS LYONS Jock’s Owner . KATE KNEELAND Trusty’s Owner . DARRYL HANDY Lady . ROSE Tramp . MONTE Train Worker . ROBERT WALKER-BRANCHAUD A Dock Worker . ROGER PAYANO TAYLOR MADE Park Bench Lady . DENITRA ISLER Production Park Bench Gentleman . .CHARLES ORR Shopkeeper . .ALLEN EARLS Directed by . CHARLIE BEAN Poodle Owner . .KELLEY BROOKS Screenplay by . .ANDREW BUJALSKI Truck Driver . CAL JOHNSON and KARI GRANLUND Riverboat Jazz Musicians . TEDDY ADAMS Produced by . BRIGHAM TAYLOR, p.g.a. MELVIN JONES Executive Producer . .DIANE L. SABATINI CORDELL HALL Director of Photography . ENRIQUE CHEDIAK, ASC DAVID HAYES Production Designer . JOHN MYHRE STEFAN KLEIN Film Editor . MELISSA BRETHERTON TANNER HAMILTON Costume Designers . .COLLEEN ATWOOD BILLY HOFFMAN TIMOTHY A. WONZIK Jim’s Buddy #1 . .JASON BURKEY Visual Eff ects Supervisor . ROBERT WEAVER Jim’s Buddy #2 . .SWIFT RICE Visual Eff ects Producer . CHRISTOPHER RAIMO Shower Guest . .MICHAELA CRONAN Original Score Composed by . JOSEPH TRAPANESE Pet Shop Owner . .PARVESH CHEENA Casting by . .RICHARD HICKS Pet Shop Customer . INGA EISS Peg & Bull’s Owner . .MATT MERCURIO Unit Production Manager . DIANE L. SABATINI Ticket Attendant . MICHAEL TOUREK First Assistant Director . JODY SPILKOMAN Tony’s Patron . JENNIFER CHRISTA PALMER First Assistant Director . .ALEX GAYNER Tramp’s Owner #1 . MICHAEL SHENEFELT Second Assistant Director . .STEPHANIE TULL Tramp’s Owner #2 . .ALEXA STAUDT Riverboat Lady . .VIRGINIA KIRBY Drummer Boy . BRAELYN RANKINS Nighttime Train Worker #1 . ALAN BOELL Nighttime Train Worker #2 . DAVID JACKSON Harmonica Man . .PATRICK “LIPS” WILLIAMS Gentleman On Street . .KALVIN KOSKELA Brakeman . TERRY KOLLER VOICE CAST Riverboat Captain . -

Kiss Me, Kate

‘A CHANCE FOR STAGE FOLKS TO SAY “HELLO”: ENTERTAINMENT AND THEATRICALITY IN KISS ME, KATE HANNAH MARIE ROBBINS DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC This dissertation is submitted to the University of Sheffield for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2017 ABSTRACT As Cole Porter’s most commercially successful Broadway musical, Kiss Me, Kate (1948) has been widely acknowledged as one of several significant works written during ‘the Golden age’ period of American musical theatre history. Through an in-depth examination of the genesis and reception of this musical and discussion of the extant analytical perspectives on the text, this thesis argues that Kiss Me, Kate has remained popular as a result of its underlying celebration of theatricality and of entertainment. Whereas previous scholarship has suggested that Porter and his co-authors, Sam and Bella Spewack, attempted to emulate Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Oklahoma! (1943) by creating their own ‘integrated musical’, this thesis demonstrates how they commented on contemporary culture, on popular art forms, and the sanctity of Shakespeare and opera in deliberately mischievous ways. By mapping the influence of Porter and the Spewacks’ previous work and their deliberate focus on theatricality and diversion in the development of this work, it shows how Kiss Me, Kate forms part of a wider trend in Broadway musicals. As a result, this study calls for a new analytical framework that distinguishes musicals like Kiss Me, Kate from the persistent methodologies that consider works exclusively through the lens of high art aesthetics. By acknowledging Porter and the Spewacks’ reflexive celebration of and commentary on entertainment, it advocates a new position for musical theatre research that will encourage the study of other similar stage and screen texts that incorporate themes from, and react to, the popular cultural sphere to which they belong. -

A Director's Approach to a Production of Alice in Wonderland for Touring

A director's approach to a production of Alice in Wonderland for touring Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Riggs, Rita Fern, 1930- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 03/10/2021 19:11:19 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/319003 A DIRECTOR’S APPROACH TO A PRODUCTION OF ALICE IN WONDERLAND FOR TOURING by Rita Riggs A Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Department of Dramatic Arts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Graduate College, University of Arizona 195k Approved: Director K ° v5 This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for an advanced degree at the University of Arizona and is deposited in the Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the dean of the Graduate College when in their judgment the proposed use of the material is in the interests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. SIGNED: TABLE OF QQHTEHTS CFAPTER PAGE Introduction I* A, STUDY OF THE $tALICE*1 STQHIES;, THE AUTHOR, AHD HISTORIES OF STAGE ADAPTATIORS . -

An Analysis of Theoni Aldredge's Life and Career Matthew Cotts Ed Mpsey

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects January 2013 An Analysis Of Theoni Aldredge's Life And Career Matthew cottS eD mpsey Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/theses Recommended Citation Dempsey, Matthew Scott, "An Analysis Of Theoni Aldredge's Life And Career" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 1413. https://commons.und.edu/theses/1413 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN ANALYSIS OF THEONI ALDREDGE’S LIFE AND CAREER by Matthew Scott Dempsey Bachelor of Arts, Minot State University, 2011 a Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Grand Forks, North Dakota May 2013 Copyright 2013 Matthew Scott Dempsey ii This thesis, submitted by Matthew Dempsey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts from the University of North Dakota, has been read by the Faculty Advisory Committee under whom the work has been done, and is hereby approved. _______________________________________ Chairperson: Emily Cherry MFA _______________________________________ Kathleen McLennan PHD _______________________________________ Ali Angelone MFA This thesis is being submitted by the appointed advisory committee as having met all of the requirements of the Graduate School at the University of North Dakota and is hereby approved. -

Rehearsal, Performance, and Management Practices by the Oregon Shakespeare Festival

Six Companies in Search of Shakespeare: Rehearsal, Performance, and Management Practices by The Oregon Shakespeare Festival, The Stratford Shakespeare Festival, The Royal Shakespeare Company, Shakespeare & Company, Shakespeare‘s Globe and The American Shakespeare Center DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Andrew Michael Blasenak, M.F.A. Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Professor Stratos Constantinidis, Advisor Professor Nena Couch Professor Beth Kattelman i Copyright by Andrew Michael Blasenak 2012 ii Abstract This dissertation examines the artistic and managerial visions of six "non-profit" theatre companies which have been dedicated to the revitalization of Shakespeare‘s plays in performance from 1935 to 2012. These six companies were The Oregon Shakespeare Festival, the Stratford Shakespeare Festival, The Royal Shakespeare Company, Shakespeare & Company, Shakespeare‘s Globe and The American Shakespeare Center. The following questions are considered in the eight chapters of this study:1) Did the re- staging of Shakespeare's plays in six "non-profit" theatre companies introduce new stagecraft and managerial strategies to these companies? 2) To what degree did the directors who re-staged Shakespeare's plays in these six "non-profit" theatre companies successfully integrate the audience in the performance? 3) How important was the coaching of actors in these six "non-profit"