The Concept of Otherness in Shakespearean Film Rathiga

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cambridge Companion Shakespeare on Film

This page intentionally left blank Film adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays are increasingly popular and now figure prominently in the study of his work and its reception. This lively Companion is a collection of critical and historical essays on the films adapted from, and inspired by, Shakespeare’s plays. An international team of leading scholars discuss Shakespearean films from a variety of perspectives:as works of art in their own right; as products of the international movie industry; in terms of cinematic and theatrical genres; and as the work of particular directors from Laurence Olivier and Orson Welles to Franco Zeffirelli and Kenneth Branagh. They also consider specific issues such as the portrayal of Shakespeare’s women and the supernatural. The emphasis is on feature films for cinema, rather than television, with strong cov- erage of Hamlet, Richard III, Macbeth, King Lear and Romeo and Juliet. A guide to further reading and a useful filmography are also provided. Russell Jackson is Reader in Shakespeare Studies and Deputy Director of the Shakespeare Institute, University of Birmingham. He has worked as a textual adviser on several feature films including Shakespeare in Love and Kenneth Branagh’s Henry V, Much Ado About Nothing, Hamlet and Love’s Labour’s Lost. He is co-editor of Shakespeare: An Illustrated Stage History (1996) and two volumes in the Players of Shakespeare series. He has also edited Oscar Wilde’s plays. THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO SHAKESPEARE ON FILM CAMBRIDGE COMPANIONS TO LITERATURE The Cambridge Companion to Old English The Cambridge Companion to William Literature Faulkner edited by Malcolm Godden and Michael edited by Philip M. -

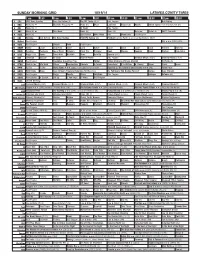

Sunday Morning Grid 10/19/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 10/19/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Paid Program Bull Riding 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Meet LazyTown Poppy Cat Noodle Action Sports From Brooklyn, N.Y. (N) 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Vista L.A. ABC7 Presents 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Winning Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Carolina Panthers at Green Bay Packers. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program I.Q. ››› (1994) (PG) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexico Cooking Cook Kitchen Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Cold. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Special (TVG) 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 34 KMEX Paid Program República Deportiva (TVG) Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División Al Punto (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Home Alone 4 ›› (2002, Comedia) French Stewart. -

Click to Download

v8n4 covers.qxd 5/13/03 1:58 PM Page c1 Volume 8, Number 4 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies & Television Action Back In Bond!? pg. 18 MeetTHE Folks GUFFMAN Arrives! WIND Howls! SPINAL’s Tapped! Names Dropped! PLUS The Blue Planet GEORGE FENTON Babes & Brits ED SHEARMUR Celebrity Studded Interviews! The Way It Was Harry Shearer, Michael McKean, MARVIN HAMLISCH Annette O’Toole, Christopher Guest, Eugene Levy, Parker Posey, David L. Lander, Bob Balaban, Rob Reiner, JaneJane Lynch,Lynch, JohnJohn MichaelMichael Higgins,Higgins, 04> Catherine O’Hara, Martin Short, Steve Martin, Tom Hanks, Barbra Streisand, Diane Keaton, Anthony Newley, Woody Allen, Robert Redford, Jamie Lee Curtis, 7225274 93704 Tony Curtis, Janet Leigh, Wolfman Jack, $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada JoeJoe DiMaggio,DiMaggio, OliverOliver North,North, Fawn Hall, Nick Nolte, Nastassja Kinski all mentioned inside! v8n4 covers.qxd 5/13/03 1:58 PM Page c2 On August 19th, all of Hollywood will be reading music. spotting editing composing orchestration contracting dubbing sync licensing music marketing publishing re-scoring prepping clearance music supervising musicians recording studios Summer Film & TV Music Special Issue. August 19, 2003 Music adds emotional resonance to moving pictures. And music creation is a vital part of Hollywood’s economy. Our Summer Film & TV Music Issue is the definitive guide to the music of movies and TV. It’s part 3 of our 4 part series, featuring “Who Scores Primetime,” “Calling Emmy,” upcoming fall films by distributor, director, music credits and much more. It’s the place to advertise your talent, product or service to the people who create the moving pictures. -

Shakespeare's Heroines in American Musical Theater

Jelena Zlatarov-Marcetic Jelena Zlatarov-Marcetic Jelena Shakespeare's Heroines in American Musical Theater Migration and Happiness Master’s thesis in English Supervisor: Eli Løfaldli Master’s thesis Master’s May 2019 Shakespeare's Heroines in American Musical Theater Musical in American Heroines Shakespeare's NTNU Faculty of Humanities Faculty Department of Language and Literature Norwegian University of Science and Technology of Science University Norwegian Jelena Zlatarov-Marcetic Shakespeare's Heroines in American Musical Theater Migration and Happiness Master’s thesis in English Supervisor: Eli Løfaldli May 2019 Norwegian University of Science and Technology Faculty of Humanities Department of Language and Literature Acknowledgements Firstly, I would like to thank my family for their unwavering support and patience, and especially my husband for his invaluable inputs. Secondly, I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Eli Løfaldli, who has taught me a lot and has shown great patience and understanding during this whole year. Thirdly, I would like to thank Kirsten Slørstad for being the kindest librarian ever, without whose help I would have had great difficulty getting hold of the necessary literature. Finally, I big thank you goes to all my friends who have shown interest in my work, let me use their libraries, and proofread my writing. Also, to Rasmus, who always knew when I needed a break. Jelena Zlatarov-Marcetic, Tynset 15 May 2019 Table of Contents Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………….…1 Adapting the Canon -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

Shak Shakespeare Shakespeare

Friday 14, 6:00pm ROMEO Y JULIETA ’64 / Ramón F. Suárez (30’) Cuba, 1964 / Documentary. Black-and- White. Filming of fragments of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet staged by the renowned Czechoslovak theatre director Otomar Kreycha. HAMLET / Laurence Olivier (135’) U.K., 1948 / Spanish subtitles / Laurence Olivier, Eileen Herlie, Basil Sydney, Felix Aylmer, Jean Simmons. Black-and-White. Magnificent adaptation of Shakespeare’s tragedy, directed by and starring Olivier. Saturday 15, 6:00pm OTHELLO / The Tragedy of Othello: The Moor of Venice / Orson Welles (92’) Italy-Morocco, 1951 / Spanish subtitles / Orson Welles, Michéal MacLiammóir, Suzanne Cloutier, Robert Coote, Michael Laurence, Joseph Cotten, Joan Fontaine. Black- and-White. Filmed in Morocco between the years 1949 and 1952. Sunday 16, 6:00pm ROMEO AND JULIET / Franco Zeffirelli (135’) Italy-U.K., 1968 / Spanish subtitles / Leonard Whiting, Olivia Hussey, Michael York, John McEnery, Pat Heywood, Robert Stephens. Thursday 20, 6:00pm MACBETH / The Tragedy of Macbeth / Roman Polanski (140’) U.K.-U.S., 1971 / Spanish subtitles / Jon Finch, Francesca Annis, Martin Shaw, Nicholas Selby, John Stride, Stephan Chase. Colour. This version of Shakespeare’s key play is co-scripted by Kenneth Tynan and director Polanski. Friday 21, 6:00pm KING LEAR / Korol Lir / Grigori Kozintsev (130’) USSR, 1970 / Spanish subtitles / Yuri Yarvet, Elsa Radzin, GalinaVolchek, Valentina Shendrikova. Black-and-White. Saturday 22, 6:00pm CHIMES AT MIDNIGHT / Orson Welles (115’) Spain-Switzerland, 1965 / in Spanish / Orson Welles, Keith Baxter, John Gielgud, Jeanne Moreau, Margaret 400 YEARS ON, Rutherford, Norman Rodway, Marina Vlady, Walter Chiari, Michael Aldridge, Fernando Rey. Black-and-White. Sunday 23, 6:00pm PROSPERO’S BOOKS / Peter Greenaway (129’) U.K.-Netherlands-France, 1991 / Spanish subtitles / John Gielgud, Michael Clark, Michel Blanc, Erland Josephson, Isabelle SHAKESPEARE Pasco. -

Sagawkit Acceptancespeechtran

Screen Actors Guild Awards Acceptance Speech Transcripts TABLE OF CONTENTS INAUGURAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...........................................................................................2 2ND ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .........................................................................................6 3RD ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...................................................................................... 11 4TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 15 5TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 20 6TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 24 7TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 28 8TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 32 9TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 36 10TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 42 11TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 48 12TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .................................................................................... -

PLAYNOTES Season: 43 Issue: 05

PLAYNOTES SEASON: 43 ISSUE: 05 BACKGROUND INFORMATION PORTLANDSTAGE The Theater of Maine INTERVIEWS & COMMENTARY AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY Discussion Series The Artistic Perspective, hosted by Artistic Director Anita Stewart, is an opportunity for audience members to delve deeper into the themes of the show through conversation with special guests. A different scholar, visiting artist, playwright, or other expert will join the discussion each time. The Artistic Perspective discussions are held after the first Sunday matinee performance. Page to Stage discussions are presented in partnership with the Portland Public Library. These discussions, led by Portland Stage artistic staff, actors, directors, and designers answer questions, share stories and explore the challenges of bringing a particular play to the stage. Page to Stage occurs at noon on the Tuesday after a show opens at the Portland Public Library’s Main Branch. Feel free to bring your lunch! Curtain Call discussions offer a rare opportunity for audience members to talk about the production with the performers. Through this forum, the audience and cast explore topics that range from the process of rehearsing and producing the text to character development to issues raised by the work Curtain Call discussions are held after the second Sunday matinee performance. All discussions are free and open to the public. Show attendance is not required. To subscribe to a discussion series performance, please call the Box Office at 207.774.0465. By Johnathan Tollins Portland Stage Company Educational Programs are generously supported through the annual donations of hundreds of individuals and businesses, as well as special funding from: The Davis Family Foundation Funded in part by a grant from our Educational Partner, the Maine Arts Commission, an independent state agency supported by the National Endowment for the Arts. -

2010 Annual Report

2010 ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents Letter from the President & CEO ......................................................................................................................5 About The Paley Center for Media ................................................................................................................... 7 Board Lists Board of Trustees ........................................................................................................................................8 Los Angeles Board of Governors ................................................................................................................ 10 Media Council Board of Governors ..............................................................................................................12 Public Programs Media As Community Events ......................................................................................................................14 INSIDEMEDIA Events .................................................................................................................................14 PALEYDOCFEST ......................................................................................................................................20 PALEYFEST: Fall TV Preview Parties ...........................................................................................................21 PALEYFEST: William S. Paley Television Festival ......................................................................................... 22 Robert M. -

The Power of Story Male Speaker

The Power of Story Male Speaker: Good morning, everyone. Welcome to day three of the Public Health Workshop, You all know from the credits in many of the favorite TV shows [out] there, and you saw how beautifully crafted are those stories in terms of conveying health promotion messages in a variety of fields. And they show many of the examples in our own field here. And we're going to have this interactive session now with them on more detail. Sandra's going to explain to you in a minute how the session is going to evolve. Sandra, next to me here -- she's the director of Hollywood Health and Society, a program of the University of Southern California Annenberg Norman Lear Center. She's known for her award-winning work on entertainment health and social change in the US and also internationally. Sandra provides resources to leading scriptwriters and producers with the goal of improving the accuracy of health and climate change-related storylines on top television programs and films. This has resulted in more than 565 aired storylines over the span of three years. She was named one of the 100 most influential Hispanics in America by Poder Magazine and has received numerous other honors, including the USAID MAQ Outstanding Achievement Award. Her Vasectomy Campaign in Brazil -- mind you, she's half Brazilian -- won seven international advertising awards including a Bronze Lion at Cannes -- the Cannes Festival, mind you -- and the Gold Medal at the London International Advertising Awards. She's a former associate faculty member of Johns Hopkins University, the School of Public Health, in fact. -

They're Tasty!

The Goodland Star-News / Tuesday, October 14, 2003 5 abigail it’s too late. The following are some of the (6) Anyone who wants to avoid say that neither I nor my husband Flu shots are FACT: Although it’s best to be people for whom influenza vac- the risk of spreading the flu (and has contracted the flu since we be- van buren vaccinated in October or Novem- cine is recommended in the United its possible complications) to a gan getting flu shots. Other excel- ber for maximum protection States: loved one or friend. Flu vaccine lent candidates who should con- good protection throughout the flu season, people (1) People 50 and older. protects not only you, but also the sider being immunized include •dear abby who are immunized in December, (2) Anyone 6 months and older people you care about. police and fire personnel, teachers, for people January and February are pro- who has medical problems such as A nasal spray form of influenza bus drivers, and people who come DEAR ABBY: Each year in the mended fail to get immunized. tected. heart or lung disease (including vaccine is newly licensed in the in contact with the public. United States, influenza kills Some presumptions that keep MYTH 3: Only people 65 and asthma), diabetes, kidney disease U.S. this year. For more informa- Readers, if you have questions 36,000 people and hospitalizes people from being vaccinated: older need the influenza vaccine. or a weak immune system. tion about it, your readers should about influenza vaccine, or any 110,000 more. -

A New Chapter

FINAL-1 Sat, Nov 30, 2019 4:06:52 PM tvupdateYour Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment For the week of December 8 - 14, 2019 A new chapter Jacqueline Toboni stars in “The L Word: Generation Q” INSIDE •Sports highlights Page 2 •TV Word Search Page 2 •Family Favorites Page 4 •Hollywood Q&A Page14 Showtime is rebooting one of its most beloved shows with “The L Word: Generation Q,” premiering Sunday, Dec. 8. The series features the return of original “The L Word” stars Jennifer Beals (“Flashdance,” 1983), Leisha Hailey (“Dead Ant,” 2017) and Katherine Moennig (“Ray Donovan”), as well as a few new faces, including Jacqueline Toboni (“Grimm”), Arienne Mandi (“The Vault”) and Leo Sheng (“Adam,” 2019). To advertise here WANTED MOTORCYCLES, SNOWMOBILES, OR ATVS GOLD/DIAMONDS please call ✦ 40 years in business; A+ rating with the BBB. ✦ For the record, there is only one authentic CASH FOR GOLD, Bay 4 (978) 946-2375 Group Page Shell PARTS & ACCESSORIES We Need: SALESMotorsports & SERVICE 5 x 3” Gold • Silver • Coins • Diamonds MASS. MOTORCYCLEWANTED1 x 3” We are the ORIGINAL and only AUTHENTIC SELLBUYTRADEINSPECTIONS CASH FOR GOLD on the Methuen line, above Enterprise Rent-A-Car at 527 So. Broadway, Rte. 28, Salem, NH • 603-898-2580 1615 SHAWSHEEN ST., TEWKSBURY, MA Open 7 Days A Week ~ www.cashforgoldinc.com 978-851-3777 WWW.BAY4MS.COM FINAL-1 Sat, Nov 30, 2019 4:06:53 PM COMCAST ADELPHIA 2 Sports Highlights Kingston CHANNEL Atkinson ESPN NESN Sunday 8:00 p.m. TNT Basketball NBA Football NCAA Division I Hockey NCAA Dartmouth at Salem Londonderry 9:00 a.m.