English Productions of Measure for Measure on Stage and Screen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, a MATTER of LIFE and DEATH/ STAIRWAY to HEAVEN (1946, 104 Min)

December 8 (XXXI:15) Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, A MATTER OF LIFE AND DEATH/ STAIRWAY TO HEAVEN (1946, 104 min) (The version of this handout on the website has color images and hot urls.) Written, Produced and Directed by Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger Music by Allan Gray Cinematography by Jack Cardiff Film Edited by Reginald Mills Camera Operator...Geoffrey Unsworth David Niven…Peter Carter Kim Hunter…June Robert Coote…Bob Kathleen Byron…An Angel Richard Attenborough…An English Pilot Bonar Colleano…An American Pilot Joan Maude…Chief Recorder Marius Goring…Conductor 71 Roger Livesey…Doctor Reeves Robert Atkins…The Vicar Bob Roberts…Dr. Gaertler Hour of Glory (1949), The Red Shoes (1948), Black Narcissus Edwin Max…Dr. Mc.Ewen (1947), A Matter of Life and Death (1946), 'I Know Where I'm Betty Potter…Mrs. Tucker Going!' (1945), A Canterbury Tale (1944), The Life and Death of Abraham Sofaer…The Judge Colonel Blimp (1943), One of Our Aircraft Is Missing (1942), 49th Raymond Massey…Abraham Farlan Parallel (1941), The Thief of Bagdad (1940), Blackout (1940), The Robert Arden…GI Playing Bottom Lion Has Wings (1939), The Edge of the World (1937), Someday Robert Beatty…US Crewman (1935), Something Always Happens (1934), C.O.D. (1932), Hotel Tommy Duggan…Patrick Aloyusius Mahoney Splendide (1932) and My Friend the King (1932). Erik…Spaniel John Longden…Narrator of introduction Emeric Pressburger (b. December 5, 1902 in Miskolc, Austria- Hungary [now Hungary] —d. February 5, 1988, age 85, in Michael Powell (b. September 30, 1905 in Kent, England—d. Saxstead, Suffolk, England) won the 1943 Oscar for Best Writing, February 19, 1990, age 84, in Gloucestershire, England) was Original Story for 49th Parallel (1941) and was nominated the nominated with Emeric Pressburger for an Oscar in 1943 for Best same year for the Best Screenplay for One of Our Aircraft Is Writing, Original Screenplay for One of Our Aircraft Is Missing Missing (1942) which he shared with Michael Powell and 49th (1942). -

Cambridge Companion Shakespeare on Film

This page intentionally left blank Film adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays are increasingly popular and now figure prominently in the study of his work and its reception. This lively Companion is a collection of critical and historical essays on the films adapted from, and inspired by, Shakespeare’s plays. An international team of leading scholars discuss Shakespearean films from a variety of perspectives:as works of art in their own right; as products of the international movie industry; in terms of cinematic and theatrical genres; and as the work of particular directors from Laurence Olivier and Orson Welles to Franco Zeffirelli and Kenneth Branagh. They also consider specific issues such as the portrayal of Shakespeare’s women and the supernatural. The emphasis is on feature films for cinema, rather than television, with strong cov- erage of Hamlet, Richard III, Macbeth, King Lear and Romeo and Juliet. A guide to further reading and a useful filmography are also provided. Russell Jackson is Reader in Shakespeare Studies and Deputy Director of the Shakespeare Institute, University of Birmingham. He has worked as a textual adviser on several feature films including Shakespeare in Love and Kenneth Branagh’s Henry V, Much Ado About Nothing, Hamlet and Love’s Labour’s Lost. He is co-editor of Shakespeare: An Illustrated Stage History (1996) and two volumes in the Players of Shakespeare series. He has also edited Oscar Wilde’s plays. THE CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO SHAKESPEARE ON FILM CAMBRIDGE COMPANIONS TO LITERATURE The Cambridge Companion to Old English The Cambridge Companion to William Literature Faulkner edited by Malcolm Godden and Michael edited by Philip M. -

The Moral Basis of Family Relationships in the Plays of Shakespeare and His Contemporaries: a Study in Renaissance Ideas

The Moral Basis of Family Relationships in the plays of Shakespeare and his Contemporaries: a Study in Renaissance Ideas. A submission for the degree of doctor of philosophy by Stephen David Collins. The Department of History of The University of York. June, 2016. ABSTRACT. Families transact their relationships in a number of ways. Alongside and in tension with the emotional and practical dealings of family life are factors of an essentially moral nature such as loyalty, gratitude, obedience, and altruism. Morality depends on ideas about how one should behave, so that, for example, deciding whether or not to save a brother's life by going to bed with his judge involves an ethical accountancy drawing on ideas of right and wrong. It is such ideas that are the focus of this study. It seeks to recover some of ethical assumptions which were in circulation in early modern England and which inform the plays of the period. A number of plays which dramatise family relationships are analysed from the imagined perspectives of original audiences whose intellectual and moral worlds are explored through specific dramatic situations. Plays are discussed as far as possible in terms of their language and plots, rather than of character, and the study is eclectic in its use of sources, though drawing largely on the extensive didactic and polemical writing on the family surviving from the period. Three aspects of family relationships are discussed: first, the shifting one between parents and children, second, that between siblings, and, third, one version of marriage, that of the remarriage of the bereaved. -

Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still Calling Her Q!

1 More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In InfiniteBody art and creative consciousness by Eva Yaa Asantewaa Tuesday, May 6, 2014 Your Host Qurrat Ann Kadwani: Still calling her Q! Eva Yaa Asantewaa Follow View my complete profile My Pages Home About Eva Yaa Asantewaa Getting to know Eva (interview) Qurrat Ann Kadwani Eva's Tarot site (photo Bolti Studios) Interview on Tarot Talk Contact Eva Name Email * Message * Send Contribute to InfiniteBody Subscribe to IB's feed Click to subscribe to InfiniteBody RSS Get InfiniteBody by Email Talented and personable Qurrat Ann Kadwani (whose solo show, They Call Me Q!, I wrote about Email address... Submit here) is back and, I hope, every bit as "wicked smart and genuinely funny" as I observed back in September. Now she's bringing the show to the Off Broadway St. Luke's Theatre , May 19-June 4, Mondays at 7pm and Wednesdays at 8pm. THEY CALL ME Q is the story of an Indian girl growing up in the Boogie Down Bronx who gracefully seeks balance between the cultural pressures brought forth by her traditional InfiniteBody Archive parents and wanting acceptance into her new culture. Along the journey, Qurrat Ann Kadwani transforms into 13 characters that have shaped her life including her parents, ► 2015 (222) Caucasian teachers, Puerto Rican classmates, and African-American friends. Laden with ▼ 2014 (648) heart and abundant humor, THEY CALL ME Q speaks to the universal search for identity ► December (55) experienced by immigrants of all nationalities. ► November (55) Program, schedule and ticket information ► October (56) ► September (42) St. -

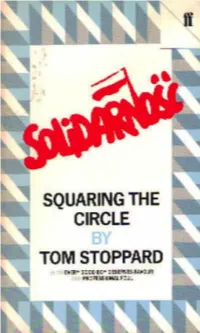

SQUARING the CIRCLE Also Available from Faber & Faber

SQUARING THE CIRCLE Also available from Faber & Faber by Tom Stoppard UNDISCOVERED COUNTRY (a version of Arthur Schnitzler's Das weite Land) ON THE RAZZLE (adapted from Johann Nestroy's Einen Jux will er sich machen) THE REAL THING THE DOG IT WAS THAT DIED and other plays FOUR PLAYS FOR RADIO Artist Descending a Staircase Where Are They Now? If You're Glad I'll be Frank Albert's Bridge SQUARING THE CIRCLE BY TOM STOPPARD t1 faber andfaber BOSTON • LONDON First published in the UK in 1984 First published in the USA in 1985 by Faber & Faber, Inc. 39 Thompson Street Winchester, MA 01890 © Tom Stoppard, 1984 All rights whatsoever in this play are strictly reserved, and all enquiries should be directed to Fraser and Dunlop (Scripts), Ltd., 91 Regent Street, London, WlR 8RU, England All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher, except for brief passages quoted by a reviewer Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Stoppard, Tom. Squaring the circle. I. Title. PR6069.T6S6 1985 822'.914 84-28732 ISBN 0-571-12538-7 (pbk.) IN TRODUC TION At the beginning of 1982, about a month after the imposition of martial law in Poland, a film producer named Fred Brogger suggested that I should write a television film about Solidarity. Thus began a saga, only moderately exceptional by these standards, which may be worth recounting as an example of the perils which sometimes attend the offspring of an Anglo-American marriage. -

Brian Tufano BSC Resume

BRIAN TUFANO BSC - Director of Photography FEATURE FILM CREDITS Special Jury Prize for Outstanding Contribution To British Film and Television - British Independent Film Awards 2002 Award for Outstanding Contribution To Film and Television - BAFTA 2001 EVERYWHERE AND NOWHERE Director: Menhaj Huda. Starring Art Malik, Amber Rose Revah, Adam Deacon, Producers: Menhaj Huda, Sam Tromans and Stella Nwimo. Stealth Films. ADULTHOOD Director: Noel Clarke Starring Noel Clarke, Adam Deacon, Red Mandrell, Producers: George Isaac, Damian Jones And Scarlett Johnson Limelight MY ZINC BED Director: Anthony Page Starring Uma Thurman, Jonathan Pryce, and Producer: Tracy Scofield Paddy Considine Rainmark Films/HBO I COULD NEVER BE YOUR WOMAN Director: Amy Heckerling Starring Michelle Pfeiffer and Paul Rudd Producer: Philippa Martinez, Scott Rudin Paramount Pictures KIDULTHOOD Director: Menhaj Huda Starring Aml Ameen, Adam Deacon Producer: Tim Cole Red Mandrell and Jamie Winstone Stealth Films/Cipher Films ONCE UPON A TIME IN Director: Shane Meadows THE MIDLANDS Producer: Andrea Calderwood Starring Robert Carlyle, Rhys Ifans, Kathy Burke. Ricky Tomlinson and Shirley Henderson Slate Films / Film Four LAST ORDERS Director: Fred Schepisi Starring: Michael Caine, Bob Hoskins, Producers: Rachel Wood, Elizabeth Robinson Tom Courtenay, Helen Mirren, Ray Winstone Scala Productions LATE NIGHT SHOPPING Director: Saul Metzstein Luke De Woolfson, James Lance, Kate Ashfield, Producer: Angus Lamont. Enzo Cilenti andShauna MacDonald Film Four Intl / Ideal World Films BILLY ELLIOT Director: Steven Daldry Julie Walters, Gary Lewis, Jamie Draven and Jamie Bell Producers: Jon Finn and Gregg Brenman. Working Title Films/Tiger Aspect Pictures BBC/Arts Council Film. 4929 Wilshire Blvd., Ste. 259 Los Angeles, CA 90010 ph 323.782.1854 fx 323.345.5690 [email protected] BRIAN TUFANO BSC - Director of Photography WOMEN TALKING DIRTY Director: Coky Giedroyc Helena Bonham-Carter, Gina McKee Producers: David Furnish and Polly Steele James Purefoy, Jimmy Nesbitt, Richard Wilson Petunia Productions. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

Study Guide for Well T S the Count of Rossillion Has Died

yale 2006 repertory theatre 40th anniversary across 2005-06 season theboards willpower! Yale Repertory Theatre’s production is part of all’s Shakespeare in American Communities: Shakespeare for a New Generation, sponsored by the National well Endowment for the Arts in cooperation with Arts Midwest. that Additional program support: ends Study Guide for well T S The Count of Rossillion has died. Following D :LGRZ DQG KHU GDXJKWHU 'LDQD :KHQ the funeral, his son Bertram leaves for Paris Helena learns that Bertram has been pursu- with Lord Lafew to serve the ailing King of ing the young Florentine maid, she, with the France. After Bertram departs, we learn :LGRZ¶VEOHVVLQJGHYLVHVDSODQ'LDQDZLOO that Helena—a young girl whom Bertram’s arrange an encounter with Bertram in which mother, the Countess of Rossillion, took into she will take him to bed in exchange for his her care after Helena’s father died—secretly prized ring, but when this encounter occurs, pines for him. Hoping to garner his affec- +HOHQD ZLOO WULFN %HUWUDP E\ WDNLQJ 'LDQD¶V tion, she follows Bertram to Paris. Helena’s place. father was a spiritual healer of great renown, 2QWKHEDWWOH¿HOG%HUWUDPKDVSURYHGKLP- and to gain the King’s favor, she will work her self a fearsome soldier, but the French Lords father’s ancient healing upon His Majesty. worry that Parolles’s cowardice threatens the The King welcomes Bertram to Paris security of the encampment. Bertram allows DQG FRQ¿UPV WKDW KLV GHDWK LV LPPLQHQW his troops to put Parolles to a test of honor in Unexpectedly, Helena which he is captured, appears in the King’s blindfolded, and tricked court and insists that Shakespeare’s Play: into revealing military she may be able to Bocaccio’s Tale secrets. -

22 August 2008 Page 1 of 6 SATURDAY 16 AUGUST 2008 Hudd …

Radio 7 Listings for 16 – 22 August 2008 Page 1 of 6 SATURDAY 16 AUGUST 2008 Hudd …. Philip Fox moon, before the ship returns to Earth. Norton …. John Rowe Futuristic tale set in 1965 written and produced by Charles SAT 00:00 Time Hops (b007k1sp) Prison Officer …. Stephen Hogan Chilton. Time's Up Director: Cherry Cookson Jet Morgan …. Andrew Faulds The children are convinced that the man from the BBC will First broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in August 2004. Lemmy Barnett …. Alfie Bass help them. But is he really what he seems? SAT 06:00 Like They've Never Been Gone (b00cz8np) Doc …. Guy Kingsley-Poynter Conclusion of the comedy sci-fi by Alan Gilbey and David Series 4 Mitch …. David Williams Richard-Fox. Episode 6 All Other Parts …. David Jacobs Stars Sara Crowe as EK6, David Harewood as RV101, Nicola It’s Tommy and Sheila’s anniversary – 40 years in showbiz! Music composed and orchestra conducted by Van Phillips. Stapleton as Steph, Paul Reynolds as Baz, Dax O'Callaghan as Lewis is hoping it’ll pass quietly and cheaply. But will a short The original 1953 recordings of this futuristic series were Max, Ian Masters as Norton, Joshua Towb as Horatio, Neville hospital stay force Tommy to start taking life easier? erased. Jason as Tailor and Margaret John as Mrs Miller. Mike Coleman's sitcom starring Roy Hudd and June Whitfield. This series was re-recorded and first broadcast on the BBC Music by Richard Attree. Ageing showbiz couple Tommy Franklin and Sheila Parr battle Light Programme in April 1958. -

Is the Principal Sponsor of Team Shakespeare. Measure for Measure Rendering: Costume Designer Virgil C

is the principal sponsor of Team Shakespeare. measure for measure rendering: Costume Designer Virgil C. Johnson rendering: Costume Designer Virgil teacher handbook Barbara Gaines Criss Henderson Table of Contents Artistic Director Executive Director Preface . .1 Art That Lives . .2 Bard’s Bio . .2 The First Folio . .3 Shakespeare’s England . .4 The Renaissance Theater . .5 Chicago Shakespeare Theater is Chicago's professional theater Courtyard-style Theater . .6 dedicated to the works of William Shakespeare. Founded as Timelines . .8 Shakespeare Repertory in 1986, the company moved to its seven-story home on Navy Pier in 1999. In its Elizabethan-style William Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure courtyard theater, 500 seats on three levels wrap around a deep Dramatis Personae . .10 thrust stage—with only nine rows separating the farthest seat from the stage. Chicago Shakespeare also features a flexible 180- The Story . .10 seat black box studio theater, a Teacher Resource Center, and a Act-by-Act Synopsis . .11 Shakespeare specialty bookstall. Something Borrowed, Something New . .12 In its first 17 seasons, the Theater has produced nearly the entire What’s in a Genre? . .14 Shakespeare canon: All’s Well That Ends Well, Antony and 1604 and All That . .14 Cleopatra, As You Like It, The Comedy of Errors, Cymbeline, To Have and To Hold? . .15 Hamlet, Henry IV Parts 1 and 2, Henry V, Henry VI Parts 1, 2 and Playnotes:The Dark God and his Dark Angel . .16 3, Julius Caesar, King John, King Lear, Love’s Labor’s Lost, Macbeth, Playnotes: Between the Lines . .17 Measure for Measure, The Merchant of Venice, The Merry Wives of Windsor, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Much Ado About Nothing, What the Critics Say . -

5 April 2019 Page 1 of 15

Radio 4 Listings for 30 March – 5 April 2019 Page 1 of 15 SATURDAY 30 MARCH 2019 gradual journey towards all I now do, I am honoured to be a daughters to the coast to find out if if the problems and mum to a fabulous autistic son. In the UK, we have thousands concerns have changed. SAT 00:00 Midnight News (m0003jxg) of autistic mothers, and indeed autistic parents & carers of all The latest national and international news from BBC Radio 4. kinds. Many bringing up their young families with love, As the women travel to their picnic by the sea in a minibus, we Followed by Weather. dedication and determination, watching their children grow and hear their stories. thrive. Do we enable and accept them? Balwinder was born and brought up in Glasgow and drives a SAT 00:30 Book of the Week (m0003jxj) Loving God, on this Mothering Sunday weekend, we ask that taxi. She was raised in a strict Sikh family and at the age of The Pianist of Yarmouk you guide and support all mothers, enabling them to gain eighteen her parents arranged her marriage. “With Mum and strength from you, cherishing all that their children will bring to Dad it was just, ‘You don’t need to study, you don’t need to Episode 5 the world, as young people deserving to be fully loved, and fully worry about work, because the only thing you’re going to be themselves. doing is getting married.’” Ammar Haj Ahmad reads Aeham Ahmad’s dramatic account of how he risked his life playing music under siege in Damascus. -

18 November 2011 Page 1 of 7

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 12 – 18 November 2011 Page 1 of 7 SATURDAY 12 NOVEMBER 2011 The struggling actor and mate Murray try out a global food Research consultant - Professor Alison Fell café, while Kate has a bad day. Directed by Pauline Harris SAT 00:00 The Legend of Sleepy Hollow by Washington Alan Davies stars in his own sitcom. Sara was a VAD Nurse (Voluntary Aid Detachment) a unit Irving (b007xrtx) Written by Ben Silburn, Tony Roche and Alan Davies. which provided medical assistance in time of war. VADs like 3. Dark Forces Alan ...... Alan Davies Sara were young women eager to "do their duty".. Sara at 24 Both fighting for the affections of the beautiful Katrina Van Murray ...... Alan Francis years of age travels from 'Connaught Hospital' Aldershot to '31 Tassel, the rivalry between Ichabod Crane and Brom Bones Kate ...... Ronni Ancona General Hospital' Cairo with 22 other nurses. There she nurses continues apace. With Debra Stephenson, Alistair MacGowan and Dave Lamb. the wounded and dying and sees the devastating effects of And now it seems that supernatural forces are about to get Producer: Jane Berthoud Typhus and Malaria on our troops. And yet she writes with good involved. First broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in June 1998. humour and energy, a fresh and vivid voice, taking a wondrous Washington Irving's supernatural classic about two love rivals SAT 06:00 A Game of Golf (b007jrr3) interest in the beauty of the landscape and the country's exotic and a headless horseman: Two couples' marital problems come to a head on the golf atmos.