4 Modern Shakespeare Festivals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1999 + Credits

1 CARL TOMS OBE FRSA 1927 - 1999 Lorraine’ Parish Church Hall. Mansfield Nottingham Journal review 16th Dec + CREDITS: All work what & where indicated. 1950 August/ Sept - Exhibited 48 designs for + C&C – Cast & Crew details on web site of stage settings and costumes at Mansfield Art Theatricaila where there are currently 104 Gallery. Nottm Eve Post 12/08/50 and also in Nottm references to be found. Journal 12/08/50 https://theatricalia.com/person/43x/carl- toms/past 1952 + Red related notes. 52 - 59 Engaged as assistant to Oliver Messel + Film credits; http://www.filmreference.com/film/2/Carl- 1953 Toms.html#ixzz4wppJE9U2 Designer for the penthouse suite at the Dorchester Hotel. London + Television credits and other work where indicated. 1957: + Denotes local references, other work and May - Apollo de Bellac - awards. Royal Court Theatre, London, ----------------------------------------------------- 57/58 - Beth - The Apollo,Shaftesbuy Ave London C&C 1927: May 29th Born - Kirkby in Ashfield 22 Kingsway. 1958 Local Schools / Colleges: March 3 rd for one week ‘A Breath of Spring. Diamond Avenue Boys School Kirkby. Theatre Royal Nottingham. Designed by High Oakham. Mansfield. Oliver Messel. Assisted by Carl Toms. Mansfield Collage of Art. (14 years old). Programme. Review - The Stage March 6th Lived in the 1940’s with his Uncle and Aunt 58/59 - No Bed for Bacon Bristol Old Vic. who ran a grocery business on Station St C&C Kirkby. *In 1950 his home was reported as being 66 Nottingham Rd Mansfield 1959 *(Nottm Journal Aug 1950) June - The Complaisant Lover Globe Conscripted into Service joining the Royal Theatre, London. -

V. Adamkus Imasi Iniciatyvos Sprendžiant Pensijas Kgb-Istams

SECOND CLASS USPS 157-580 — THE LITHUANIAN NATIONAL NEWSPAPER 19807 CHEROKEE AVENUE CLEVELAND, OHIO 44119 VOL. LXXXVII 2002 DECEMBER - GRUODŽIO 3, Nr. 47 DIRVA LIETUVIŲ TAUTINĖS MINTIES LAIKRAŠTIS V. ADAMKUS IMASI INICIATYVOS SPRENDŽIANT PENSIJAS KGB-ISTAMS Vilnius, lapkričio mėn. 19 Šiuo metu Seime yra re d. ELTA. Prezidentas ragina gistruotos dvi Valstybinių pen Vyriausybę kuo greičiau spręs sijų įstatymo pataisos, kurios ti susidariusią koliziją, kad turėtų patikslinti susidariusią žmonės, nusikaltę prieš lietu teisinę padėtį. “Deja, Seimas vių tautą, nebūtų įvertinami už nerado laiko jų svarstyti”, - nuopelnus Lietuvos valstybei apgailestavo Prezidento ir jiems nebūtų mokamos vals atstovas. tybinės pensijos. Gyventojų genocido ir re “Tai rimta problema. Prezi zistencijos tyrimų centro di dentas artimiausiu metu ben rektorė D.Kuodytė kreipėsi į draus ir su Seimo Pirmininku, socialinės apsaugos ir darbo ir su Premjeru - reikia šią koli ministrę V.Blinkevičiūtę su ziją išspręsti”, - informavo žur prašymu sustabdyti D.Prevelio nalistus Prezidento patarėjas pasirašyto minėto įsakymo Darius Kuolys po V.Adamkaus veikimą, nes jis tik dar labiau pokalbio su socialinės apsau sukomplikuoja ir taip sudėtin gos ir darbo ministre Vilija gą situaciją. Po susitikimo su Blinkevičiūte ir Gyventojų ge Prezidentu ji teigė, kad minė nocido ir rezistencijos tyrimų tas įsakymas turėtų būti at centro direktore Dalia Kuodyte. šauktas tada, kai bus pataisytas ELTA primena, jog spalio Valstybinių pensijų įstatymas. Po JAV prezidento George W. Bush kalbos Vilniuje lapkričio 23 d. Lietuvos prezidentas Valdas Adamkus dėkoja jam už tartus lietuvių tautai žodžius. A/P 24 dieną “Sodros” vadovas V.Blinkevičiūtė sutiko, kad Dalius Prevelis, nors jau buvo aiškumą Valstybinių pensijų įteikęs prašymą atleisti iš pa įstatyme galutinai turėtų įtvir RUSIJOS UŽSIENIO REIKALŲ MINISTRAS IR LIETUVOS SEIMO reigų, pasirašė įsakymą, kuriuo tinti Seimas. -

Backlash Over Blair's School Revolution

Section:GDN BE PaGe:1 Edition Date:050912 Edition:01 Zone:S Sent at 11/9/2005 19:33 cYanmaGentaYellowblack Chris Patten: How the Tories lost the plot This Section Page 32 Lady Macbeth, four-letter needle- work and learning from Cate Blanchett. Judi Dench in her prime Simon Schama: G2, page 22 Amy Jenkins: America will never The me generation be the same again is now in charge G2 Page 8 G2 Page 2 £0.60 Monday 12.09.05 Published in London and Manchester guardian.co.uk Bad’day mate Aussies lose their grip Column five Backlash over The shape of things Blair’s school to come revolution Alan Rusbridger elcome to the Berliner Guardian. No, City academy plans condemned we won’t go on calling it that by ex-education secretary Morris for long, and Wyes, it’s an inel- An acceleration of plans to reform state education authorities as “commissioners egant name. education, including the speeding up of of education and champions of stan- We tried many alternatives, related the creation of the independently funded dards”, rather than direct providers. either to size or to the European origins city academy schools, will be announced The academies replace failing schools, of the format. In the end, “the Berliner” today by Tony Blair. normally on new sites, in challenging stuck. But in a short time we hope we But the increasingly controversial inner-city areas. The number of acade- can revert to being simply the Guardian. nature of the policy was highlighted when mies will rise to between 40 and 50 by Many things about today’s paper are the former education secretary Estelle next September. -

Click Here to Download The

$10 OFF $10 OFF WELLNESS MEMBERSHIP MICROCHIP New Clients Only All locations Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. Expires 3/31/2020 Expires 3/31/2020 Free First Office Exams FREE EXAM Extended Hours Complete Physical Exam Included New Clients Only Multiple Locations Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. 4 x 2” ad www.forevervets.com Expires 3/31/2020 Your Community Voice for 50 Years PONTEYour Community Voice VED for 50 YearsRA RRecorecorPONTE VEDRA dderer entertainment EEXXTRATRA! ! Featuring TV listings, streaming information, sports schedules, puzzles and more! June 25 - July 1, 2020 has a new home at INSIDE: THE LINKS! Sports listings, 1361 S. 13th Ave., Ste. 140 sports quizzes Jacksonville Beach and more Pages 18-19 Offering: · Hydrafacials · RF Microneedling · Body Contouring · B12 Complex / Lipolean Injections ‘Hamilton’ – Disney+ streams Broadway hit Get Skinny with it! “Hamilton” begins streaming Friday on Disney+. (904) 999-0977 1 x 5” ad www.SkinnyJax.com Kathleen Floryan PONTE VEDRA IS A HOT MARKET! REALTOR® Broker Associate BUYER CLOSED THIS IN 5 DAYS! 315 Park Forest Dr. Ponte Vedra, Fl 32081 Price $720,000 Beds 4/Bath 3 Built 2020 Sq Ft. 3,291 904-687-5146 [email protected] Call me to help www.kathleenfloryan.com you buy or sell. 4 x 3” ad BY GEORGE DICKIE Disney+ brings a Broadway smash to What’s Available NOW On streaming with the T American television has a proud mistreated peasant who finds her tradition of bringing award- prince, though she admitted later to winning stage productions to the nerves playing opposite decorated small screen. -

Shakespeare on Film, Video & Stage

William Shakespeare on Film, Video and Stage Titles in bold red font with an asterisk (*) represent the crème de la crème – first choice titles in each category. These are the titles you’ll probably want to explore first. Titles in bold black font are the second- tier – outstanding films that are the next level of artistry and craftsmanship. Once you have experienced the top tier, these are where you should go next. They may not represent the highest achievement in each genre, but they are definitely a cut above the rest. Finally, the titles which are in a regular black font constitute the rest of the films within the genre. I would be the first to admit that some of these may actually be worthy of being “ranked” more highly, but it is a ridiculously subjective matter. Bibliography Shakespeare on Silent Film Robert Hamilton Ball, Theatre Arts Books, 1968. (Reissued by Routledge, 2016.) Shakespeare and the Film Roger Manvell, Praeger, 1971. Shakespeare on Film Jack J. Jorgens, Indiana University Press, 1977. Shakespeare on Television: An Anthology of Essays and Reviews J.C. Bulman, H.R. Coursen, eds., UPNE, 1988. The BBC Shakespeare Plays: Making the Televised Canon Susan Willis, The University of North Carolina Press, 1991. Shakespeare on Screen: An International Filmography and Videography Kenneth S. Rothwell, Neil Schuman Pub., 1991. Still in Movement: Shakespeare on Screen Lorne M. Buchman, Oxford University Press, 1991. Shakespeare Observed: Studies in Performance on Stage and Screen Samuel Crowl, Ohio University Press, 1992. Shakespeare and the Moving Image: The Plays on Film and Television Anthony Davies & Stanley Wells, eds., Cambridge University Press, 1994. -

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 15 – 21 May 2021 Page 1 of 10 SATURDAY 15 MAY 2021 Producer: Jill Waters Comedy Chat Show About Shame and Guilt

Radio 4 Extra Listings for 15 – 21 May 2021 Page 1 of 10 SATURDAY 15 MAY 2021 Producer: Jill Waters comedy chat show about shame and guilt. First broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in June 1998. Each week Stephen invites a different eminent guest into his SAT 00:00 Planet B (b00j0hqr) SAT 03:00 Mrs Henry Wood - East Lynne (m0006ljw) virtual confessional box to make three 'confessions' are made to Series 1 5. The Yearning of a Broken Heart him. This is a cue for some remarkable storytelling, and 5. The Smart Money No sooner has Lady Isabel been betrayed by the wicked Francis surprising insights. John and Medley are transported to a world of orgies and Levison than she is left unrecognisably disfigured by a terrible We’re used to hearing celebrity interviews where stars are circuses, where the slaves seek a new leader. train crash. persuaded to show off about their achievements and talk about Ten-part series about a mystery virtual world. What is to become of her? their proudest moments. Stephen isn't interested in that. He Written by Paul May. Mrs Henry Wood's novel dramatised by Michael Bakewell. doesn’t want to know what his guests are proud of, he wants to John ...... Gunnar Cauthery Mrs Henry Wood ... Rosemary Leach know what makes them ashamed. That’s surely the way to find Lioba ...... Donnla Hughes Lady Isabel ... Moir Leslie out what really makes a person tick. Stephen and his guest Medley ...... Lizzy Watts Mr Carlyle ... David Collings reflect with empathy and humour on things like why we get Cerberus ..... -

The Ultimate On-Demand Music Library

2020 CATALOGUE Classical music Opera The ultimate Dance Jazz on-demand music library The ultimate on-demand music video library for classical music, jazz and dance As of 2020, Mezzo and medici.tv are part of Les Echos - Le Parisien media group and join their forces to bring the best of classical music, jazz and dance to a growing audience. Thanks to their complementary catalogues, Mezzo and medici.tv offer today an on-demand catalogue of 1000 titles, about 1500 hours of programmes, constantly renewed thanks to an ambitious content acquisition strategy, with more than 300 performances filmed each year, including live events. A catalogue with no equal, featuring carefully curated programmes, and a wide selection of musical styles and artists: • The hits everyone wants to watch but also hidden gems... • New prodigies, the stars of today, the legends of the past... • Recitals, opera, symphonic or sacred music... • Baroque to today’s classics, jazz, world music, classical or contemporary dance... • The greatest concert halls, opera houses, festivals in the world... Mezzo and medici.tv have them all, for you to discover and explore! A unique offering, a must for the most demanding music lovers, and a perfect introduction for the newcomers. Mezzo and medici.tv can deliver a large selection of programmes to set up the perfect video library for classical music, jazz and dance, with accurate metadata and appealing images - then refresh each month with new titles. 300 filmed performances each year 1000 titles available about 1500 hours already available in 190 countries 2 Table of contents Highlights P. -

Rannual Report 2019

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 3 Dorset Rise, London EC4Y 8EN 020 7822 2810 – [email protected] www.rts.org.uk RtS PATRONS PRINCIPAL PATRONS BBC ITV Channel 4 Sky INTERNATIONAL PATRONS A+E Networks International Netflix Discovery Networks The Walt Disney Company Facebook Viacom International Media Networks Liberty Global WarnerMedia NBCUniversal International YouTube MAJOR PATRONS Accenture IMG Studios All3Media ITN Amazon Video KPMG Audio Network Motion Content Group Avid netgem.tv Boston Consulting Group NTT Data BT OC&C Channel 5 Pinewood TV Studios Deloitte S4C EndemolShine Sargent-Disc Enders Analysis Spencer Stuart Entertainment One STV Group Finecast The Trade Desk Freeview UKTV Fremantle Vice Gravity Media Virgin Media IBM YouView RTS PATRONS Autocue Lumina Search Digital Television Group Mission Bay Grass Valley PriceWaterhouseCoopers Isle of Media Raidió Teilifís Éireann 2 BOARD OF TRUSTEES REPORT TO MEMBERS Forewords by RTS Chair and CEO 4 I Achievements and performance 6 1 Education and skills 8 2 Engaging with the public 16 3 Promoting thought leadership 24 4 Awards and recognition 30 5 The nations and regions 36 6 Membership and volunteers 40 7 Financial support 42 8 Our people 44 9 Summary of national events 46 10 Centre reports 48 II Governance and finance 58 1 Structure, governance and management 59 2 Objectives and activities 60 3 Financial review 60 4 Plans for future periods 62 5 Administrative details 62 Independent auditor’s report 64 Financial statements 66 Notes to the financial statements 70 Who’s who at the RTS 84 Royal Television Society AGM 2020 In light of the restrictions in place due to the Covid-19 crisis, the Society is reviewing the timing and logistics involved in holding its 2020 AGM. -

Features Shorts Animation Documentaries 1 Documentarytable of Contents Coming Soon

2010 /2 011 features shorts animation documentaries 1 documentarytable of contents coming soon Latvian Film in 2010 Introduction by Ilze Gailīte Holmberg 3 Features 2010/2011 4 Features Coming soon 7 Shorts 2010/2011 15 Shorts Coming soon 18 Animation 2010/2011 19 Animation Coming soon 30 Documentaries 2010/2011 35 Documentaries Coming soon 54 Index of English Titles 70 Index of Original Titles 71 Index of Directors 72 Index of Production Companies 73 Adresses of Production Companies 74 Useful Adresses 76 2 latvian film in 2010 Travelling and Locally venue – Riga Meetings – aimed at bringing together 2010 has been the best year ever for Latvian film at Baltic and Nordic film producers and enhancing international festivals – our documentaries, animation regional collaboration. As a result of these meetings, and feature films were represented at Berlinale, Cannes, several regional collaboration projects are underway. Annecy, Venice, Leipzig, Pusan and Amsterdam. 2011 has also started on a successful note – Filming in Latvia this year’s Berlinale selected the outspoken social The interest of foreign filmmakers in filming in documentary homo@lv (dir. Kaspars Goba) for Riga and Latvia has grown considerably in 2010 mainly its Panorama Dokumente, and the lovable puppet due to the opening of the Riga Film Fund, but also due animation Acorn Boy (dir. Dace Rīdūze) for the to the benevolent effect of the Nordic – Baltic meeting Generation Kplus programme. point, and the activity of Latvian producers looking to Local audience numbers for Latvian films have also attract foreign productions in times when national film risen in 2010, although still lagging at a modest 7% funding has diminished radically. -

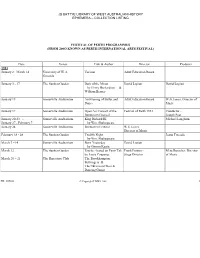

Js Battye Library of West Australian History Ephemera – Collection Listing

JS BATTYE LIBRARY OF WEST AUSTRALIAN HISTORY EPHEMERA – COLLECTION LISTING FESTIVAL OF PERTH PROGRAMMES (FROM 200O KNOWN AS PERTH INTERNATIONAL ARTS FESTIVAL) Date Venue Title & Author Director Producer 1953 January 2 - March 14 University of W.A. Various Adult Education Board Grounds January 3 - 17 The Sunken Garden Dark of the Moon David Lopian David Lopian by Henry Richardson & William Berney January 15 Somerville Auditorium An Evening of Ballet and Adult Education Board W.G.James, Director of Dance Music January 17 Somerville Auditorium Open Air Concert of the Festival of Perth 1953 Conductor - Beethoven Festival Joseph Post January 20-23 - Somerville Auditorium King Richard III Michael Langham January 27 - February 7 by Wm. Shakespeare January 24 Somerville Auditorium Beethoven Festival W.G.James Director of Music February 18 - 28 The Sunken Garden Twelfth Night Jeana Tweedie by Wm. Shakespeare March 3 –14 Somerville Auditorium Born Yesterday David Lopian by Garson Kanin March 12 The Sunken Garden Psyche - based on Fairy Tale Frank Ponton - Meta Russcher, Director by Louis Couperus Stage Director of Music March 20 – 21 The Repertory Club The Brookhampton Bellringers & The Ukrainian Choir & Dancing Group PR 10960 © Copyright LISWA 2001 1 JS BATTYE LIBRARY OF WEST AUSTRALIAN HISTORY PRIVATE ARCHIVES – COLLECTION LISTING March 25 The Repertory Theatre The Picture of Dorian Gray Sydney Davis by Oscar Wilde Undated His Majesty's Theatre When We are Married Frank Ponton - Michael Langham by J.B.Priestley Stage Director 1954.00 December 30 - March 20 Various Various Flyer January The Sunken Garden Peer Gynt Adult Education Board David Lopian by Henrik Ibsen January 7 - 31 Art Gallery of W.A. -

Dossier Du Spectacle

04/02 - 29/02 maRdI au sAmedi 19H00 1H20 CORRESPONDANCE AVEC LA MOUETTE d’après ANTON TCHEKHOV & LIKA MIZINOVA | mise en scène NICOLAS STRUVE c’est avec plaisIr qUe jE Vous ébouIllantEraIs DOSSIER DU SPECTACLE Adresse Contact presse Les Déchargeurs Les Déchargeurs 3 rue des Déchargeurs 75001 PARIS 07 61 16 55 72 Métro Châtelet [email protected] Réservations Sur internet 24/7 www.lesdechargeurs.fr Contact diffusion Par téléphone 01 42 36 00 50 Cie l’oubli des cerisiers du lundi au samedi de 17h30 à 23h [email protected] Tarifs : 28 - 20 - 14 - 10 € [email protected] 1 GÉnÉRiQuE D’après la correspondance entre Anton Tchekhov et Lika Mizinova Traduction, adaptation, mise en scène Nicolas Struve Geste scénographique Georges Vafias Lumières Antoine Duris Chorégraphie Sophie Mayer Jeu David Gouhier, Stéphanie Schwartzbrod Coréalisation La Reine Blanche - Les Déchargeurs & Cie l’Oubli Des Cerisers Production Cie l’Oubli des cerisiers Avec le soutien du théâtre de l’Abbaye (St Maur Des Fossés) et RAV!V (réseau des Arts Vivants en Île de France) Création LES DÉCHARGEURS - PARIS 4 au 29 février 2020, mardi au samedi à 19h Durée 1h20 A PROPoS DE la PIèCE Anton Tchekhov, Lika Mizinova, 10 ans de correspondance. Ils se plaisent, se désirent, se titillent, s’agacent, se manquent. Elle se verra figurer dans la Mouette sous les traits de Nina. UN tEXTE Il existe 64 lettres de Tchekhov à Mizinova et 98 d’elle à lui. Les lettres de Mizinova n’avaient jamais été traduites en français. Je m’y suis attelé, comme à celles de Tchekhov. -

2 Days in New York

Mongrel Media Presents 2 DAYS IN NEW YORK A FIL M B Y JULIE DEPLY (91 min., France/ Germany 2012) Language : English Official Selection: 2012 Sundance Film Festival 2012 Tribeca Film Festival Distribution Publicity Bonne Smith 1028 Queen Street West Star PR Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6J 1H6 Tel: 416-488-4436 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 Fax: 416-488-8438 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com High res stills may be downloaded from http://www.mongrelmedia.com/press.html SYNOPSIS Hip ta lk-radio host and journalist Mingus (Chris Rock) and his French photographer girlfriend, Marion (Julie Delpy), live cozily in a New York apartment with their cat and two young children from previous relationships. But when Marion's jolly father (played by Delpy’s real-life dad, Albert Delpy), her oversexed sister, and her sister's outrageous boyfriend unceremoniously descend upon them for an overseas visit, it initiates two unforgettable days of family mayhem. With their unabashed openness and sexual frankness, the triumvirate is bereft of boundaries or filters. and no one is left unscathed in its wake. The visitors push every button in the couple’s relationship, truly putting it to the test. How will the couple fare. when the French come to New York? 2 ABOUT THE FILM It’s the next big step: meeting the relatives. Maybe you get a little nervous, take a little while to warm up to everybody, but, hopefully, everything will go smoothly. But somebody forgot to warn poor Mingus: HERE COME THE FRENCH.