Is the Principal Sponsor of Team Shakespeare. Measure for Measure Rendering: Costume Designer Virgil C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Moral Basis of Family Relationships in the Plays of Shakespeare and His Contemporaries: a Study in Renaissance Ideas

The Moral Basis of Family Relationships in the plays of Shakespeare and his Contemporaries: a Study in Renaissance Ideas. A submission for the degree of doctor of philosophy by Stephen David Collins. The Department of History of The University of York. June, 2016. ABSTRACT. Families transact their relationships in a number of ways. Alongside and in tension with the emotional and practical dealings of family life are factors of an essentially moral nature such as loyalty, gratitude, obedience, and altruism. Morality depends on ideas about how one should behave, so that, for example, deciding whether or not to save a brother's life by going to bed with his judge involves an ethical accountancy drawing on ideas of right and wrong. It is such ideas that are the focus of this study. It seeks to recover some of ethical assumptions which were in circulation in early modern England and which inform the plays of the period. A number of plays which dramatise family relationships are analysed from the imagined perspectives of original audiences whose intellectual and moral worlds are explored through specific dramatic situations. Plays are discussed as far as possible in terms of their language and plots, rather than of character, and the study is eclectic in its use of sources, though drawing largely on the extensive didactic and polemical writing on the family surviving from the period. Three aspects of family relationships are discussed: first, the shifting one between parents and children, second, that between siblings, and, third, one version of marriage, that of the remarriage of the bereaved. -

Journal of Arts & Humanities

Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 08, Issue 07, 2019: 28-34 Article Received: 05-06-2019 Accepted: 17-06-2019 Available Online: 21-06-2019 ISSN: 2167-9045 (Print), 2167-9053 (Online) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18533/journal.v8i7.1672 Tactics of Power in Measure for Measure Min Jiao1 ABSTRACT In Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure, sexuality is of primary concern, which predicts characters’ behaviors, and drives the narrative progression. The play seems to be inquiring into the central question as to whether power, in particular, state power, can keep a tight rein of sexuality. This article explores into the functions of sexuality in the narrative, and the play’s self-contradictory conclusions about female and male sexuality. It argues that the play’s self-contradictory conclusion about male sexuality and female sexuality manifests the operation of different discourses on sexuality, with the first one predominantly a quasi-scientific discourse, and the latter one, still a medieval conception of sexuality grounded on religious discourse. The difference, however, manifests the transition from a medieval ideology to a nascent capitalism ideology in the discourse of sexuality. Keywords: Measure for Measure, Power, Sexuality, Ideology. This is an open access article under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Recent interpretations of Measure for Measure usually centers around the power tactics in relation to female’s economic status and identity. Lyndal Roper has argued that “as the Reformation was domesticated—as it closed convents and -

Tackling Challenging Issues in Shakespeare for Young Audiences

Shrews, Moneylenders, Soldiers, and Moors: Tackling Challenging Issues in Shakespeare for Young Audiences DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Elizabeth Harelik, M.A. Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2016 Dissertation Committee: Professor Lesley Ferris, Adviser Professor Jennifer Schlueter Professor Shilarna Stokes Professor Robin Post Copyright by Elizabeth Harelik 2016 Abstract Shakespeare’s plays are often a staple of the secondary school curriculum, and, more and more, theatre artists and educators are introducing young people to his works through performance. While these performances offer an engaging way for students to access these complex texts, they also often bring up topics and themes that might be challenging to discuss with young people. To give just a few examples, The Taming of the Shrew contains blatant sexism and gender violence; The Merchant of Venice features a multitude of anti-Semitic slurs; Othello shows characters displaying overtly racist attitudes towards its title character; and Henry V has several scenes of wartime violence. These themes are important, timely, and crucial to discuss with young people, but how can directors, actors, and teachers use Shakespeare’s work as a springboard to begin these conversations? In this research project, I explore twenty-first century productions of the four plays mentioned above. All of the productions studied were done in the United States by professional or university companies, either for young audiences or with young people as performers. I look at the various ways that practitioners have adapted these plays, from abridgments that retain basic plot points but reduce running time, to versions incorporating significant audience participation, to reimaginings created by or with student performers. -

Study Guide for Well T S the Count of Rossillion Has Died

yale 2006 repertory theatre 40th anniversary across 2005-06 season theboards willpower! Yale Repertory Theatre’s production is part of all’s Shakespeare in American Communities: Shakespeare for a New Generation, sponsored by the National well Endowment for the Arts in cooperation with Arts Midwest. that Additional program support: ends Study Guide for well T S The Count of Rossillion has died. Following D :LGRZ DQG KHU GDXJKWHU 'LDQD :KHQ the funeral, his son Bertram leaves for Paris Helena learns that Bertram has been pursu- with Lord Lafew to serve the ailing King of ing the young Florentine maid, she, with the France. After Bertram departs, we learn :LGRZ¶VEOHVVLQJGHYLVHVDSODQ'LDQDZLOO that Helena—a young girl whom Bertram’s arrange an encounter with Bertram in which mother, the Countess of Rossillion, took into she will take him to bed in exchange for his her care after Helena’s father died—secretly prized ring, but when this encounter occurs, pines for him. Hoping to garner his affec- +HOHQD ZLOO WULFN %HUWUDP E\ WDNLQJ 'LDQD¶V tion, she follows Bertram to Paris. Helena’s place. father was a spiritual healer of great renown, 2QWKHEDWWOH¿HOG%HUWUDPKDVSURYHGKLP- and to gain the King’s favor, she will work her self a fearsome soldier, but the French Lords father’s ancient healing upon His Majesty. worry that Parolles’s cowardice threatens the The King welcomes Bertram to Paris security of the encampment. Bertram allows DQG FRQ¿UPV WKDW KLV GHDWK LV LPPLQHQW his troops to put Parolles to a test of honor in Unexpectedly, Helena which he is captured, appears in the King’s blindfolded, and tricked court and insists that Shakespeare’s Play: into revealing military she may be able to Bocaccio’s Tale secrets. -

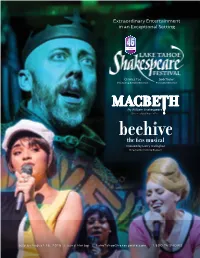

Extraordinary Entertainment in an Exceptional Setting

Extraordinary Entertainment in an Exceptional Setting Charles Fee Bob Taylor Producing Artistic Director Executive Director By William Shakespeare Directed by Charles Fee Created by Larry Gallagher Directed by Victoria Bussert July 6–August 26, 2018 | Sand Harbor | L akeTahoeShakespeare.com | 1.800.74.SHOWS Enriching lives, inspiring new possibilities. At U.S. Bank, we believe art enriches and inspires our community. That’s why we support the visual and performing arts organizations that push our creativity and passion to new levels. When we test the limits of possible, we fi nd more ways to shine. usbank.com/communitypossible U.S. Bank is proud to support the Lake Tahoe Shakespeare Festival. Incline Village Branch 923 Tahoe Blvd. Incline Village, NV 775.831.4780 ©2017 U.S. Bank. Member FDIC. 171120c 8.17 “World’s Most Ethical Companies” and “Ethisphere” names and marks are registered trademarks of Ethisphere LLC. 2018 Board of Directors Patricia Engels, Chair Michael Chamberlain, Vice Chair Atam Lalchandani, Treasurer Mary Ann Peoples, Secretary Wayne Cameron Scott Crawford Katharine Elek Amanda Flangas John Iannucci Vicki Kahn Charles Fee Bob Taylor Nancy Kennedy Producing Artistic Director Executive Director Roberta Klein David Loury Vicki McGowen Dear Friends, Judy Prutzman Welcome to the 46th season of Lake Tahoe Shakespeare Festival, Nevada’s largest professional, non-profit Julie Rauchle theater and provider of educational outreach programming! Forty-six years of Shakespeare at Lake Tahoe D.G. Menchetti, Director Emeritus is a remarkable achievement made possible by the visionary founders and leaders of this company, upon whose shoulders we all stand, and supported by the extraordinary generosity of this community, our board Allen Misher, Director Emeritus of directors, staff, volunteers, and the many artists who have created hundreds of evenings of astonishing Warren Trepp, Honorary Founder entertainment under the stars. -

Misogyny, Critical Dichotomy and Other Problems with the Interpretation of Measure for Measure Jillanne Schulte Denison University

Articulāte Volume 8 Article 2 2003 Misogyny, Critical Dichotomy and other Problems with the Interpretation of Measure for Measure Jillanne Schulte Denison University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.denison.edu/articulate Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Schulte, Jillanne (2003) "Misogyny, Critical Dichotomy and other Problems with the Interpretation of Measure for Measure," Articulāte: Vol. 8 , Article 2. Available at: http://digitalcommons.denison.edu/articulate/vol8/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Denison Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articulāte by an authorized editor of Denison Digital Commons. assert that Isabella is actually attracted to Angelo and Angelo Winner of the 20O3 Robert T. Wilson Award for Scholarly Writing bears the brunt of the misogyny in the play. Despite all the tries to seduce her because "Men corrupt women because Misogyny, Critical Dichotomy and other Problems with the Interpretation of evidence of Angelo's bad character, he is often ignored, while women are corruptible, receptive as well as vulnerable to Isabella is vilified as an evil seductress. Isabella's chastity is sexual use" (95). McCandless ignores the fact that Isabel Measure for Measure often a central issue, she is likely to fall into one of two resists being corrupted and is not in the least receptive to Jillanne Schulte '05 categories: saint or whore. Female critics do take an interest Angelo's advances. However, McCandless does bring up in Isabel's chastity, but they do not use it as a tool to classify the idea of Lucio sexualizing Isabella which is a primary cause voyeuristically eavesdrops on Isabella's conversation to Measure for Measure is the Shakespeare play with her. -

A Midsummer Night's Dream

SUPPORT FOR THE 2021 SEASON OF THE TOM PATTERSON THEATRE IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY PRODUCTION SUPPORT IS GENEROUSLY PROVIDED BY THE HARKINS & MANNING FAMILIES IN MEMORY OF SUSAN & JIM HARKINS LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Welcome to the Stratford Festival. It is a great privilege to gather and share stories on this beautiful territory, which has been the site of human activity — and therefore storytelling — for many thousands of years. We wish to honour the ancestral guardians of this land and its waterways: the Anishinaabe, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, the Wendat, and the Attiwonderonk. Today many Indigenous peoples continue to call this land home and act as its stewards, and this responsibility extends to all peoples, to share and care for this land for generations to come. A MESSAGE FROM OUR ARTISTIC DIRECTOR WORLDS WITHOUT WALLS Two young people are in love. They’re next- cocoon, and now it’s time to emerge in a door neighbours, but their families don’t get blaze of new colour, with lively, searching on. So they’re not allowed to meet: all they work that deals with profound questions and can do is whisper sweet nothings to each prompts us to think and see in new ways. other through a small gap in the garden wall between them. Eventually, they plan to While I do intend to program in future run off together – but on the night of their seasons all the plays we’d planned to elopement, a terrible accident of fate impels present in 2020, I also know we can’t just them both to take their own lives. -

The Limitations of Political Theology in Measure for Measure

religions Article Bondage of the Will: The Limitations of Political Theology in Measure for Measure Bethany C. Besteman Department of English, Catholic University of America, Washington, DC 20064, USA; [email protected] Received: 2 December 2018; Accepted: 1 January 2019; Published: 3 January 2019 Abstract: Although Peter Lake and Debora Shuger have argued that Measure for Measure is hostile to Calvinist theology, I argue that the play’s world presents a Reformed theo-political sensibility, not in order to criticize Calvinism, but to reveal limitations in dominant political theories. Reformed theology informs the world of the play, especially with regards to the corruption of the human will through original sin. Politically, the sinfulness of the human will raises concerns about governments—despite Biblical commands to obey leaders, how can they be trusted if subject to the same corruption of will as citizens? Close analysis of key passages reveals that while individual characters in Measure suggest solutions that account in part for the corruption of the will, none of their political theories manage to contain the radical effects of sin in Angelo’s will. Despite this failure, restorative justice occurs in Act 5, indicating forces outside of human authority and will account for the comedic ending. This gestures towards the dependence of governments in a post-Reformation world on providential protection and reveals why the Reformed belief in the limitations of the human will point towards the collapse of the theory of the King’s two bodies. Keywords: original sin; political theology; human will 1. Introduction Measure for Measure has generated layers of scholarship exploring the complex relationship between religion and politics represented in the play. -

Parolles the Play “All’S Well That Ends Well”

THE MAN PAROLLES THE PLAY “ALL’S WELL THAT ENDS WELL” THE FACTS WRITTEN: Shakespeare wrote the play in 1602 between “Troilus and Cressida” and “Measure for Measure”; all three “comedies” are considered to be Shakespeare’s “Problem Plays”. PUBLISHED: The play was not published until its inclusion twenty-one years later in the 1623 Folio. AGE: The Bard was 38 years old when he wrote the play. (Shakespeare B.1564-D.1616) CHRONO: The play falls in 25th place in the canon of 39 plays -- a dark period in Shakespeare’s writing, coincidentally just prior to the 1603 recurrence of bubonic plague which temporarily closed the theaters off and on until the Great Fire of London in 1666 which effectively halted the tragic epidemic. GENRE: Even though the play is considered a “comedy” it defies being placed in that genre. “Modern criticism has sought other terms than comedy and the label ‘problem play’ was first attached to it in 1896 by English scholar, Frederick S. Boas. Frederick S. Boas (1896): The play produces neither “simple joy nor pain; we are excited, fascinated, perplexed; for the issues raised preclude a completely satisfactory outcome”. The Arden Shakespeare scholars add to Boas’ comments: “This is arguably the very source of the play’s interest for us, as it Page 2 complicates and holds up for criticism the wish-fulfilling logic of comedy itself. Helena desires to assure herself and us that: ‘All’s well that ends well yet, / Though time seems so adverse and means unfit.’ Even if the action ‘ends well’, the ‘means unfit’ by which it does so must challenge the comic claim. -

Staging Executions: the Theater of Punishment in Early Modern England Sarah N

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2007 Staging Executions: The Theater of Punishment in Early Modern England Sarah N. Redmond Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY THE COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES “STAGING EXECUTIONS: THE THEATER OF PUNISHMENT IN EARLY MODERN ENGLAND” By SARAH N. REDMOND This thesis submitted to the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2007 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Sarah N. Redmond, Defended on the 2nd of April, 2007 _______________________ Daniel Vitkus Professor Directing Thesis _______________________ Gary Taylor Committee Member _______________________ Celia Daileader Committee Member Approved: _______________________ Nancy Warren Director of Graduate Studies The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my major professor, Dr. Daniel Vitkus, for his wonderful and invaluable ideas concerning this project, and Dr. Gary Taylor and Dr. Celia Daileader for serving on my thesis committee. I would also like to thank Drs. Daileader and Vitkus for their courses in the Fall 2006, which inspired elements of this thesis. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures . v Abstract . vi INTRODUCTION: Executions in Early Modern England: Practices, Conventions, Experiences, and Interpretations . .1 CHAPTER ONE: “Blood is an Incessant Crier”: Sensationalist Accounts of Crime and Punishment in Early Modern Print Culture . .11 CHAPTER TWO “Violence Prevails”: Death on the Stage in Kyd’s The Spanish Tragedy and Middleton’s The Revenger’s Tragedy . -

Of Marian Intercession in Shakespeare's Plays of Justice And

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Selected Papers of the Ohio Valley Shakespeare Literary Magazines Conference March 2016 The “local habitation” of Marian Intercession in Shakespeare’s Plays of Justice and Mercy Elizabeth Burow-Flak Valparaiso University, [email protected] Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/spovsc Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Burow-Flak, Elizabeth (2014) "The “local habitation” of Marian Intercession in Shakespeare’s Plays of Justice and Mercy," Selected Papers of the Ohio Valley Shakespeare Conference: Vol. 7 , Article 3. Available at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/spovsc/vol7/iss2014/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Literary Magazines at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Selected Papers of the Ohio Valley Shakespeare Conference by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The “local habitation” of Marian Intercession in Shakespeare’s Plays of Justice and Mercy Elizabeth Burow-Flak, Valparaiso University asting doubt on the stories of the lovers in the woods, Theseus, in the speech on which this year’s conference is C based, singles out lunatics and lovers for perceiving what is not present. But the poet’s eye, he says, “doth glance from heaven to earth, from earth to heaven,” giving “things unknown…a local habitation and a name” (5.1.14-18). -

Article (Published Version)

Article 'Our Other Shakespeare'? Thomas Middleton and the Canon ERNE, Lukas Christian Reference ERNE, Lukas Christian. 'Our Other Shakespeare'? Thomas Middleton and the Canon. Modern Philology, 2010, vol. 107, no. 3, p. 493-505 Available at: http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:14484 Disclaimer: layout of this document may differ from the published version. 1 / 1 492 MODERN PHILOLOGY absorbs and reinterprets a vast array of Renaissance cultural systems. "Our other Shakespeare": Thomas Middleton What is outside and what is inside, the corporeal world and the mental and the Canon one, are "similar"; they are vivified and governed by the divine spirit in Walker's that emanates from the Sun, "the body of the anima mundi" LUKAS ERNE correct interpretation. 51 Campanella's philosopher has a sacred role, in that by fathoming the mysterious dynamics of the real through scien- University of Geneva tific research, he performs a religious ritual that celebrates God's infi- nite wisdom. To T. S. Eliot, Middleton was the author of "six or seven great plays." 1 It turns out that he is more than that. The dramatic canon as defined by the Oxford Middleton—under the general editorship of Gary Taylor and John Lavagnino, leading a team of seventy-five contributors—con- sists of eighteen sole-authored plays, ten extant collaborative plays, and two adaptations of plays written by someone else. The thirty plays, writ ten for at least seven different companies, cover the full generic range of early modern drama: eight tragedies, fourteen comedies, two English history plays, and six tragicomedies. These figures invite comparison with Shakespeare: ten tragedies, thirteen comedies, ten or (if we count Edward III) eleven histories, and five tragicomedies or romances (if we add Pericles and < Two Noble Kinsmen to those in the First Folio).