Midsummer Night's Dream

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Moral Basis of Family Relationships in the Plays of Shakespeare and His Contemporaries: a Study in Renaissance Ideas

The Moral Basis of Family Relationships in the plays of Shakespeare and his Contemporaries: a Study in Renaissance Ideas. A submission for the degree of doctor of philosophy by Stephen David Collins. The Department of History of The University of York. June, 2016. ABSTRACT. Families transact their relationships in a number of ways. Alongside and in tension with the emotional and practical dealings of family life are factors of an essentially moral nature such as loyalty, gratitude, obedience, and altruism. Morality depends on ideas about how one should behave, so that, for example, deciding whether or not to save a brother's life by going to bed with his judge involves an ethical accountancy drawing on ideas of right and wrong. It is such ideas that are the focus of this study. It seeks to recover some of ethical assumptions which were in circulation in early modern England and which inform the plays of the period. A number of plays which dramatise family relationships are analysed from the imagined perspectives of original audiences whose intellectual and moral worlds are explored through specific dramatic situations. Plays are discussed as far as possible in terms of their language and plots, rather than of character, and the study is eclectic in its use of sources, though drawing largely on the extensive didactic and polemical writing on the family surviving from the period. Three aspects of family relationships are discussed: first, the shifting one between parents and children, second, that between siblings, and, third, one version of marriage, that of the remarriage of the bereaved. -

Study Guide for Well T S the Count of Rossillion Has Died

yale 2006 repertory theatre 40th anniversary across 2005-06 season theboards willpower! Yale Repertory Theatre’s production is part of all’s Shakespeare in American Communities: Shakespeare for a New Generation, sponsored by the National well Endowment for the Arts in cooperation with Arts Midwest. that Additional program support: ends Study Guide for well T S The Count of Rossillion has died. Following D :LGRZ DQG KHU GDXJKWHU 'LDQD :KHQ the funeral, his son Bertram leaves for Paris Helena learns that Bertram has been pursu- with Lord Lafew to serve the ailing King of ing the young Florentine maid, she, with the France. After Bertram departs, we learn :LGRZ¶VEOHVVLQJGHYLVHVDSODQ'LDQDZLOO that Helena—a young girl whom Bertram’s arrange an encounter with Bertram in which mother, the Countess of Rossillion, took into she will take him to bed in exchange for his her care after Helena’s father died—secretly prized ring, but when this encounter occurs, pines for him. Hoping to garner his affec- +HOHQD ZLOO WULFN %HUWUDP E\ WDNLQJ 'LDQD¶V tion, she follows Bertram to Paris. Helena’s place. father was a spiritual healer of great renown, 2QWKHEDWWOH¿HOG%HUWUDPKDVSURYHGKLP- and to gain the King’s favor, she will work her self a fearsome soldier, but the French Lords father’s ancient healing upon His Majesty. worry that Parolles’s cowardice threatens the The King welcomes Bertram to Paris security of the encampment. Bertram allows DQG FRQ¿UPV WKDW KLV GHDWK LV LPPLQHQW his troops to put Parolles to a test of honor in Unexpectedly, Helena which he is captured, appears in the King’s blindfolded, and tricked court and insists that Shakespeare’s Play: into revealing military she may be able to Bocaccio’s Tale secrets. -

Is the Principal Sponsor of Team Shakespeare. Measure for Measure Rendering: Costume Designer Virgil C

is the principal sponsor of Team Shakespeare. measure for measure rendering: Costume Designer Virgil C. Johnson rendering: Costume Designer Virgil teacher handbook Barbara Gaines Criss Henderson Table of Contents Artistic Director Executive Director Preface . .1 Art That Lives . .2 Bard’s Bio . .2 The First Folio . .3 Shakespeare’s England . .4 The Renaissance Theater . .5 Chicago Shakespeare Theater is Chicago's professional theater Courtyard-style Theater . .6 dedicated to the works of William Shakespeare. Founded as Timelines . .8 Shakespeare Repertory in 1986, the company moved to its seven-story home on Navy Pier in 1999. In its Elizabethan-style William Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure courtyard theater, 500 seats on three levels wrap around a deep Dramatis Personae . .10 thrust stage—with only nine rows separating the farthest seat from the stage. Chicago Shakespeare also features a flexible 180- The Story . .10 seat black box studio theater, a Teacher Resource Center, and a Act-by-Act Synopsis . .11 Shakespeare specialty bookstall. Something Borrowed, Something New . .12 In its first 17 seasons, the Theater has produced nearly the entire What’s in a Genre? . .14 Shakespeare canon: All’s Well That Ends Well, Antony and 1604 and All That . .14 Cleopatra, As You Like It, The Comedy of Errors, Cymbeline, To Have and To Hold? . .15 Hamlet, Henry IV Parts 1 and 2, Henry V, Henry VI Parts 1, 2 and Playnotes:The Dark God and his Dark Angel . .16 3, Julius Caesar, King John, King Lear, Love’s Labor’s Lost, Macbeth, Playnotes: Between the Lines . .17 Measure for Measure, The Merchant of Venice, The Merry Wives of Windsor, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Much Ado About Nothing, What the Critics Say . -

Parolles the Play “All’S Well That Ends Well”

THE MAN PAROLLES THE PLAY “ALL’S WELL THAT ENDS WELL” THE FACTS WRITTEN: Shakespeare wrote the play in 1602 between “Troilus and Cressida” and “Measure for Measure”; all three “comedies” are considered to be Shakespeare’s “Problem Plays”. PUBLISHED: The play was not published until its inclusion twenty-one years later in the 1623 Folio. AGE: The Bard was 38 years old when he wrote the play. (Shakespeare B.1564-D.1616) CHRONO: The play falls in 25th place in the canon of 39 plays -- a dark period in Shakespeare’s writing, coincidentally just prior to the 1603 recurrence of bubonic plague which temporarily closed the theaters off and on until the Great Fire of London in 1666 which effectively halted the tragic epidemic. GENRE: Even though the play is considered a “comedy” it defies being placed in that genre. “Modern criticism has sought other terms than comedy and the label ‘problem play’ was first attached to it in 1896 by English scholar, Frederick S. Boas. Frederick S. Boas (1896): The play produces neither “simple joy nor pain; we are excited, fascinated, perplexed; for the issues raised preclude a completely satisfactory outcome”. The Arden Shakespeare scholars add to Boas’ comments: “This is arguably the very source of the play’s interest for us, as it Page 2 complicates and holds up for criticism the wish-fulfilling logic of comedy itself. Helena desires to assure herself and us that: ‘All’s well that ends well yet, / Though time seems so adverse and means unfit.’ Even if the action ‘ends well’, the ‘means unfit’ by which it does so must challenge the comic claim. -

Of Marian Intercession in Shakespeare's Plays of Justice And

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Selected Papers of the Ohio Valley Shakespeare Literary Magazines Conference March 2016 The “local habitation” of Marian Intercession in Shakespeare’s Plays of Justice and Mercy Elizabeth Burow-Flak Valparaiso University, [email protected] Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/spovsc Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Burow-Flak, Elizabeth (2014) "The “local habitation” of Marian Intercession in Shakespeare’s Plays of Justice and Mercy," Selected Papers of the Ohio Valley Shakespeare Conference: Vol. 7 , Article 3. Available at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/spovsc/vol7/iss2014/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Literary Magazines at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Selected Papers of the Ohio Valley Shakespeare Conference by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The “local habitation” of Marian Intercession in Shakespeare’s Plays of Justice and Mercy Elizabeth Burow-Flak, Valparaiso University asting doubt on the stories of the lovers in the woods, Theseus, in the speech on which this year’s conference is C based, singles out lunatics and lovers for perceiving what is not present. But the poet’s eye, he says, “doth glance from heaven to earth, from earth to heaven,” giving “things unknown…a local habitation and a name” (5.1.14-18). -

Bed-Trick and Forced Marriages. Shakespeare's Distortion Of

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by HAL Université de Tours Bed-trick and forced marriages. Shakespeare's distortion of romantic comedy motifs in Measure for Measure Fr´ed´eriqueFouassier-Tate To cite this version: Fr´ed´eriqueFouassier-Tate. Bed-trick and forced marriages. Shakespeare's distortion of ro- mantic comedy motifs in Measure for Measure. Sillages Critiques, Presses de l'Universit´ede Paris-Sorbonne, 2013. <hal-01213963> HAL Id: hal-01213963 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01213963 Submitted on 9 Oct 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L'archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destin´eeau d´ep^otet `ala diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publi´esou non, lished or not. The documents may come from ´emanant des ´etablissements d'enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche fran¸caisou ´etrangers,des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou priv´es. Bed-trick and forced marriages. Shakespeare’s distortion of romantic comedy motifs in Measure for Measure The genre of Measure for Measure keeps baffling critics. Although the Folio ranks it among the comedies, it is conventionally defined as a “Problem Play”1, a genre exploding the very notion of genre itself. Although Measure for Measure ends with marriages and thus looks like a comedy, it is devoid of celebration and its ending resolves none of the tensions aroused by the action. The Problem Plays in general, and Measure for Measure in particular, especially contrast with Shakespeare‟s earlier, “romantic” comedies although one finds in it some of their features and patterns. -

English Productions of Measure for Measure on Stage and Screen

English Productions of Measure for Measure on Stage and Screen: The Play’s Indeterminacy and the Authority of Performance Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Department of English and Creative Writing Lancaster University March, 2016 Rachod Nusen Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own work, and has not been submitted in substantially the same form for the award of a higher degree elsewhere. Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my supervisor, Professor Alison Findlay. Without her advice, kindness and patience, I would be completely lost. It is magical how she could help a man who knew so little about Shakespeare in performance to complete this thesis. I am forever indebted to her. I am also indebted to Dr. Liz Oakley-Brown, Professor Geraldine Harris, Dr. Karen Juers-Munby, Dr. Kamilla Elliott, Professor Hilary Hinds and Professor Stuart Hampton-Reeves for their helpful suggestions during the annual, upgrade, mock viva and viva panels. I would like to acknowledge the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive, the National Theatre Archive, the Shakespeare’s Globe Library and Archives, the Theatre Collection at the University of Bristol, the National Art Library and the Folger Shakespeare Library on where many of my materials are based. Moreover, I am extremely grateful to Mr. Phil Willmott who gave me an opportunity to interview him. I also would like to take this opportunity to show my appreciation to Thailand’s Office of the Higher Education Commission for finically supporting my study and Chiang Mai Rajabhat University for allowing me to pursue it. -

All's Well That Ends Well and Shakespeare's Marriage1

All’s Well That Ends Well R. BRIAN and Shakespeare’s Marriage1 PARKER Résumé : Cette note revient sur le peu de faits connus du mariage de Shakes- peare,faits qui semblent indiquer une union plus ou moins imposée par lafamille d’une femme enceinte, pour proposer une dimension biographique de cette comédie tardive. Justement, l’un des principaux facteurs qui font qualifier All’s Well That Ends Well de « comédie problématique » est le rôle inhabituel joué par le mariage comme marqueur, non pas de la réalisation du désir de deux jeunes amoureux, mais plutôt du triomphe de l’héroïne de la pièce au depens du jeune homme, qui avait résisté à un tel mariage. Ce triomphe s’effectue par un stratégème faisant en sorte que le jeune homme se trouve obligé d’accepter la jeune femme déjà enceinte, et le mélange d’amertume et de honte marquant son attitude aurait bien pu être projeté sur le personnage par un dramaturge plus agé qui reconnaissait, dans son texte source, l’image miroir d’une situation de sa jeunesse. hough most criticism of All’s Well That Ends Well pays a great deal of Tattention to parallels between the play and Shakespeare’s sonnets, none of the recent studies or editions considers it in relation to Shakespeare’s marriage.2 The resemblances, however (and, of course, the concomitant dangers of oversimple interpretation), are quite striking. Stripped of special pleading, the documentary facts of the marriage are these. On 27 November 1582 a licence was recorded in the Bishop’s Register of Worcester for William Shakespeare to marry Anne Whateley of Temple Grafton, a village outside Stratford-on-Avon. -

Measure for Measure 2018 Study Guide

American Players Theatre Presents William Shakespeare’s MEASURE FOR MEASURE 2018 STUDY GUIDE American Players Theatre / PO Box 819 / Spring Green, WI 53588 www.americanplayers.org Measure for Measure by William Shakespeare 2018 Study Guide All photos by Liz Lauren Many Thanks! THANKS TO THE FOLLOWING SPONSORS FOR MAKING OUR PROGRAM POSSIBLE Dennis & Naomi Bahcall * Tom & Renee Boldt * Ronni Jones APT Children’s Fund at the Madison Community Foundation * Dane Arts * Rob & Mary Gooze * IKI Manufacturing, Inc. * Kohler Foundation, Inc. * Pepsi-Cola Bottling Company * Herzfeld Foundation * Sauk County UW-Extension, Arts and Culture Committee THANKS ALSO TO OUR MAJOR EDUCATION SPONSORS This project was also supported in part by a grant from the Wisconsin Arts Board with funds from the State of Wisconsin. American Players Theatre’s productions of As You Like It and Measure for Measure are part of Shakespeare in American Communities: Shakespeare for a New Generation, sponsored by the National Endowment for the Arts in cooperation with Arts Midwest. Who’s Who in Measure for Measure In order of appearance The Duke (James Ridge) Escalus (Gavin Lawrence) After making a show of leaving A lord, he urges a more lenient the city, he disguises himself as government. “Friar Ludowick” in order to walk unnoticed among the citizens of his corrupt dukedom. Varria (Carolyn Hoerdemann) Angelo (Marcus Truschinski) A close friend of the duke. The duke’s cold and authoritarian deputy, he falls violently in love with Isabella, but finally marries Mariana. Claudio (Roberto Tolentino) Juliet (Cher Desiree Àlvarez) A young gentleman, he is Beloved of Claudio, she is not his condemned to death for wife but is pregnant with his child. -

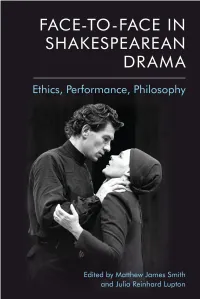

Macbeth in the Dark 132 Devin Byker

Face-to-Face in Shakespearean Drama 66053_Smith053_Smith & LLupton.inddupton.indd i 110/05/190/05/19 12:5012:50 PMPM 66053_Smith053_Smith & LLupton.inddupton.indd iiii 110/05/190/05/19 12:5012:50 PMPM Face-to-Face in Shakespearean Drama Ethics, Performance, Philosophy Edited by Matthew James Smith and Julia Reinhard Lupton 66053_Smith053_Smith & LLupton.inddupton.indd iiiiii 110/05/190/05/19 12:5012:50 PMPM Edinburgh University Press is one of the leading university presses in the UK. We publish academic books and journals in our selected subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, combining cutting-edge scholarship with high editorial and production values to produce academic works of lasting importance. For more information visit our website: edinburghuniversitypress.com © editorial matter and organisation Matthew James Smith and Julia Reinhard Lupton, 2019 © the chapters their several authors, 2019 Edinburgh University Press Ltd The Tun – Holyrood Road 12(2f) Jackson’s Entry Edinburgh EH8 8PJ Typeset in 11/13 Adobe Sabon by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd, and printed and bound in Great Britain. A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978 1 4744 3568 0 (hardback) ISBN 978 1 4744 3570 3 (webready PDF) ISBN 978 1 4744 3571 0 (epub) The right of the contributors to be identifi ed as the authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, and the Copyright and Related Rights Regulations 2003 (SI No. 2498). 66053_Smith053_Smith & LLupton.inddupton.indd iviv 110/05/190/05/19 12:5012:50 PMPM Contents List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgements viii Introduction 1 Matthew James Smith and Julia Reinhard Lupton Part I: Foundational Face Work 1. -

A Contextual Exploration of Morality and Religion in Shakespeare's Measure for Measure John A

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 Taking Drastic Measures: A Contextual Exploration of Morality and Religion in Shakespeare's Measure for Measure John A. Greer Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF THEATRE TAKING DRASTIC MEASURES: A CONTEXTUAL EXPLORATION OF MORALITY AND RELIGION IN SHAKESPEARE’S MEASURE FOR MEASURE By JOHN A. GREER A Thesis submitted to the School of Theatre in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2005 The members of the Committee approve the Thesis of John A. Greer defended on March 17, 2005. Laura Edmondson Professor Directing Thesis Mary Karen Dahl Committee Member Carrie Sandahl Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT .................................................................................................. iv 1. Introduction ............................................................................................ 1 2. A Contextual Exploration of Morality in Early Seventeenth Century England ............................................................................................ 11 3. “The Devil Can Cite Scripture for his Purpose”: An Exploration of the Religious Context of Measure for Measure.............................................. 30 4. Exceeding -

Discovering Literature Teachers' Notes: Shakespeare, Measure For

The British Library | www.bl.uk Discovering Literature: Shakespeare Teachers’ Notes Curriculum subject English Literature Key Stage 4 and 5 Author or text William Shakespeare, Measure for Measure Theme A ‘problem play’ Rationale What is Measure for Measure’s problem? The play confronts us with questions about sex, morality and power, which challenge us as readers and audiences. It was defined as a comedy in Shakespeare’s First Folio (1623) but it pushed the boundaries of the genre, and was labelled by F S Boas as a ‘problem play’ (1895). In these activities students will debate why the play is so problematic, through engagement with critics’ views, performance clips and photos. Focusing on four characters – Isabella, Angelo, Mariana and the Duke – they will also use drama to explore some of the play’s most problematic moments. Does the play resolve these problems at the end? Are the problems still relevant in today’s world? And are problematic texts sometimes the most powerful? 1 The British Library | www.bl.uk Content Primary sources from the website • Shakespeare’s First Folio (1623) • Coleridge’s notes on Measure for Measure (early 19th century) • Photograph of John Gielgud, Peter Brook and Anthony Quayle, Measure for Measure (1950) • Photographs of Mariah Gale and Kurt Egyiawan in Measure for Measure at the Globe (2015) Recommended reading from the website • Measure for Measure, What’s the problem? by Kate Chedzgoy • Gender in Measure for Measure by Kathleen McLuskie • An introduction to Shakespeare’s comedy by John Mullan External links • Angelo’s offer: a clip from Act 2, Scene 4 of Measure for Measure directed by David Thacker (1994).