Carve the Gutter Help Determine the I’M Often Asked, “What’S the Point of the Gutter”? While Direction of Cut

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

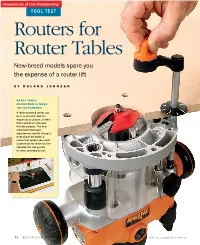

Routers for Router Tables New-Breed Models Spare You the Expense of a Router Lift

Compliments of Fine Woodworking TOOL TEST Routers for Router Tables New-breed models spare you the expense of a router lift BY ROLAND JOHNSON ABOVE-TABLE ADJUSTMENTS MAKE THE DIFFERENCE A table-mounted router can be very versatile. But it’s important to choose a router that’s designed expressly for that purpose. The best allow both bit-height adjustments and bit changes from above the table. A router that makes you reach underneath for these routine adjustments will quickly become annoying to use. 54 FINE WOODWO R K in G Photo, this page (right): Michael Pekovich outers are among the most versatile tools in the shop—the go-to gear Height adjustment Rwhen you want molded edges on lumber, dadoes in sheet stock, mortises for Crank it up. All the tools for adjusting loose tenons, or multiple curved pieces bit height worked well. Graduated that match a template. dials on the Porter-Cable Routers are no longer just handheld and the Triton are not tools. More and more woodworkers keep very useful. one mounted in a table. That gives more precise control over a variety of work, us- ing bits that otherwise would be too big to use safely. A table allows the use of feather- boards, hold-downs, a miter gauge, and other aids that won’t work with a hand- held router. With a table-mounted router, you can create moldings on large or small stock, make raised panels using large bits, cut sliding dovetails, and much more. Until recently, the best way to marry router and table was with a router lift, an expensive device that holds the router and allows you to change bits and adjust cut- ting height from above the table. -

Drying of Pharmaceutical Powders Using an Agitated Filter Dryer

Drying of Pharmaceutical Powders Using An Agitated Filter Dryer Wei Li Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Institute of Particle Science and Engineering December 2014 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his/her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The right of Wei Li to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. - ii - Acknowledgements I would first like to express my gratitude to Professor Kevin J. Roberts and Tariq Mahmud for their help and supervision throughout the course of this research work. I very appreciate that I spent such a fulfilled time to work in the field of Chemical Engineering especially in process engineering an area that I am so interested in. I am deeply grateful to them that they introduced me to the field of chemical engineering a discipline that I am much more proficient in. I would also like to thank the technical staff in School of Chemical and Process Engineering, in particular Steve Caddick, Peter Dawson, John Cran and Simon Lloyd for their support in building up the experimental facilities needed for this research as well as for carrying out repairs and relocating to the filter dryer rig. I would also like to extend my appreciation to Stephen Terry from electronics workshop for his help for developing and implementing the LabVIEW system needed to control the experimental rigs used. -

A Paper on Two Spindle Drilling Head

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395 -0056 Volume: 04 Issue: 04 | Apr -2017 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072 A Paper on Two Spindle Drilling Head Dnyaneshwar B Bharad1, Rahul D Gawande2, Pratik D Ghangale3, Rahul K Gunjal4, Prof.A.S.Autade5,Prof.P.P.Darade6 1BE Student, Mechanical, SND COE & RC, Yeola, Maharashtra, India 2BE Student, Mechanical, SND COE & RC, Yeola, Maharashtra, India 3BE Student, Mechanical, SND COE & RC, Yeola, Maharashtra, India 4BE Student, Mechanical, SND COE & RC, Yeola, Maharashtra, India 5,6Asst. Prof. Mechanical, SND COE & RC, Yeola, Maharashtra, India ---------------------------------------------------------------------***--------------------------------------------------------------------- Abstract - Generally, the growth of Indian manufacturing In this system, motions are obtained either by raising the sector is largely depends on productivity & quality. work table or it can be done by lowering the drills head. The Productivity depends upon various factors, one of the major centre distance between the drill spindles are adjusted in factors is efficiency with which the operation activities are such a way that spindle are connected to the main spindle carried out in the industry. Productivity can be highly by universal joints. In mass production work drill jigs are improved by reducing the machining time and combining generally used for guiding the drills in the work piece. It is the operations etc. As the name indicates twin spindle necessary to achieve the accurate results. Drilling depth can drilling machines have two spindles driven by a single power not be estimated properly. Different size of hole can not be head, and these two spindles holding the drill bits are fed drilled without changing the drill bit. -

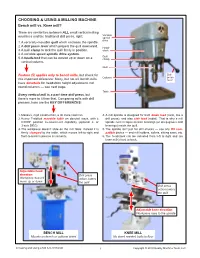

Choosing & Using a Milling Machine

CHOOSING & USING A MILLING MACHINE Bench mill vs. Knee mill? There are similarities between ALL small vertical milling Variable machines and the traditional drill press, right: speed drive 1. A vertically-movable quill which encloses the spindle. 2. A drill press lever which propels the quill downward. Head- 3. A quill clamp to lock the quill firmly in position. stock 4. A variable-speed spindle drive system. Quill 5. A headstock that can be moved up or down on a clamp vertical column. Quill Feature (5) applies only to bench mills, but check for Drill Column press this important difference: Many, but not all, bench mills lever have dovetails for headstock height adjustment, not round columns — see next page. Table Every vertical mill is a part-time drill press, but there’s more to it than that. Comparing mills with drill presses, here are the KEY DIFFERENCES: 1. Massive, rigid construction, a lot more cast iron. 4. A mill spindle is designed for both down load (axial, like a 2. Heavy T-slotted movable table on dovetail ways, with ± drill press), and also side load (radial). That is why a mill 0.0005″ position measurement capability (optional 2- or spindle runs in tapered roller bearings (or deep-groove ball 3-axis DRO). bearings) inside the quill. 3. The workpiece doesn’t slide on the mill table: instead it is 5. The spindle isn’t just for drill chucks — use any R8 com- firmly clamped to the table, which moves left-to-right and patible device — end mill holders, collets, slitting saws, etc. -

The Complete Illustrated Guide to Shaping Wood / Lonnie Bird

The COMPLETE ILLUSTRATED Guide to ShapingWood LONNIE BIRD ➤ Squares, Circles, and Ellipses ➤ Edge Treatments and Moldings ➤ Coves, Reeds, and Flutes ➤ Bent and Laminated Curves ➤ Turned and Carved Shapes The COMPLETE ILLUSTRATED Guide to ShapingWood TJ51-1-2008 IMUS 7/UOA0069-Shaping Wood W:9.25”xH:10.875” Wood TJ51-1-2008 IMUS 7/UOA0069-Shaping 175L EX 128White A M/A(D) The COMPLETE ILLUSTRATED Guide to ShapingWood LONNIE B IRD t TJ51-1-2008 IMUS 7/UOA0069-Shaping Wood W:9.25”xH:10.875” Wood TJ51-1-2008 IMUS 7/UOA0069-Shaping 175L EX 128White A M/A Magenta(D) Text © 2001 by Lonnie Bird Photographs © 2001 by Lonnie Bird Illustrations © 2001 by The Taunton Press, Inc. All rights reserved. Pp The Taunton Press, Inc., 63 South Main Street, PO Box 5506, Newtown, CT 06470-5506 e-mail: [email protected] DESIGN: Lori Wendin LAYOU T: Suzi Yannes ILLUSTRATOR: Mario Ferro PHOTOGRAPHER: Lonnie Bird LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA: Bird, Lonnie. The complete illustrated guide to shaping wood / Lonnie Bird. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN-13: 978-1-56158-400-0 ISBN-10: 1-56158-400-2 1. Woodwork. I. Title. TT180 .B57 2001 TJ51-1-2008 IMUS 7/UOA0069-Shaping Wood W:9.25”xH:10.875” Wood TJ51-1-2008 IMUS 7/UOA0069-Shaping 175L EX 128White A M/A Magenta(D) 684’.08--dc21 2001027430 Printed in Thailand 1098765 About Your Safety: Working with wood is inherently dangerous. Using hand or power tools improperly or ignoring safety practices can lead to permanent injury or even death. -

Study Unit Toolholding Systems You’Ve Studied the Process of Machining and the Various Types of Machine Tools That Are Used in Manufacturing

Study Unit Toolholding Systems You’ve studied the process of machining and the various types of machine tools that are used in manufacturing. In this unit, you’ll take a closer look at the interface between the machine tools and the work piece: the toolholder and cutting tool. In today’s modern manufacturing environ ment, many sophisti- Preview Preview cated machine tools are available, including manual control and computer numerical control, or CNC, machines with spe- cial accessories to aid high-speed machining. Many of these new machine tools are very expensive and have the ability to machine quickly and precisely. However, if a careless deci- sion is made regarding a cutting tool and its toolholder, poor product quality will result no matter how sophisticated the machine. In this unit, you’ll learn some of the fundamental characteristics that most toolholders have in common, and what information is needed to select the proper toolholder. When you complete this study unit, you’ll be able to • Understand the fundamental characteristics of toolhold- ers used in various machine tools • Describe how a toolholder affects the quality of the machining operation • Interpret national standards for tool and toolholder iden- tification systems • Recognize the differences in toolholder tapers and the proper applications for each type of taper • Explain the effects of toolholder concentricity and imbalance • Access information from manufacturers about toolholder selection Remember to regularly check “My Courses” on your student homepage. Your instructor -

TD10093 CNC Drag Knife 03

File name: TD10093_CNC_Drag_Knife_0312A Rev: 0312A Date: 3/28/2012 Product Identification: CNC Drag Knife The CNC Drag Knife uses a carbide knife to cut through thin materials like adhesive-backed sign vinyl, cardboard, paper, plastic, and metal sheet. The knife swivels and rotates freely on two ball bearings, cutting as the CNC mill drags it around the design profile. It fits any ¼ inch toolholder or collet. The CNC Drag Knife comes fully assembled with one 45 degree blade. The 45 degree blade CNC Drag Knife is ideal for cutting sign vinyl. A 60 degree blade is also available and is recommended for other materials. Both the 45 degree and 60 degree blades may be ordered as replacement parts using the part numbers below: Product Name Tormach Part Number CNC Drag Knife 32440 60 Degree Replacement Blade 32441 45 Degree Replacement Blade 32442 The CNC Drag Knife is composed of a 0.250 inch diameter brass housing that holds the following components: carbide knife blade with internal (floating head) ball bearing, external ball bearing, steel spacer, spring, set screw. A hex wrench is included with the CNC Drag Knife kit and used to set spring preload to adjust knife pressure and cut depth. Page: 1 of 8 – TD10093_CNC_Drag_Knife_0312A 204 Moravian Valley Rd, Suite N, Waunakee, WI 53597 – phone 608.849.8381 – fax 209.885.4534 www.tormach.com – © 2012 Tormach LLC® – Specifications are subject to change without notice CAUTION: Before using the CNC Drag Knife, verify the CNC mills spindle is turned off and/or the spindle speed is set to 0 RPM. -

Woodworking Glossary, a Comprehensive List of Woodworking Terms and Their Definitions That Will Help You Understand More About Woodworking

Welcome to the Woodworking Glossary, a comprehensive list of woodworking terms and their definitions that will help you understand more about woodworking. Each word has a complete definition, and several have links to other pages that further explain the term. Enjoy. Woodworking Glossary A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z | #'s | A | A-Frame This is a common and strong building and construction shape where you place two side pieces in the orientation of the legs of a letter "A" shape, and then cross brace the middle. This is useful on project ends, and bases where strength is needed. Abrasive Abrasive is a term use to describe sandpaper typically. This is a material that grinds or abrades material, most commonly wood, to change the surface texture. Using Abrasive papers means using sandpaper in most cases, and you can use it on wood, or on a finish in between coats or for leveling. Absolute Humidity The absolute humidity of the air is a measurement of the amount of water that is in the air. This is without regard to the temperature, and is a measure of how much water vapor is being held in the surrounding air. Acetone Acetone is a solvent that you can use to clean parts, or remove grease. Acetone is useful for removing and cutting grease on a wooden bench top that has become contaminated with oil. Across the Grain When looking at the grain of a piece of wood, if you were to scratch the piece perpendicular to the direction of the grain, this would be an across the grain scratch. -

Design and Analysis of Machine Tool Spindle for Special Purpose Machines (SPM) and Standardizing the Design Using Autodesk Inventor (I-Logic)

International Journal for Ignited Minds (IJIMIINDS) Design and Analysis of Machine Tool Spindle for Special Purpose Machines (SPM) and Standardizing the Design Using Autodesk Inventor (I-Logic) Harish Ra, Chandan Rb, Prahalad Wc & Shivappa H Ad aPG Student, Dept. Mechanical Engineering , Dr AIT, Bangalore, India. bAsst Prof, Dept. Mechanical Engineering , Dr AIT, Bangalore, India. cdeputy General Manager, Bosch Ltd, Bangalore, India. dAsst Prof, Dept. Mechanical Engineering , Dr AIT, Bangalore, India. ABSTRACT The work focuses on designing a machine tool spindle for SPM to carry out Face-milling operation on the given work-piece. The machine tool spindle is one of the major mechanical components in any machining center. The main structural properties of the spindle generally depend on the dimensions of the shaft, motor, tool holder, bearings and the design configuration of the overall spindle assembly. The bearing arrangements are defined by the type of operation, the cutting forces acting and the life of bearings. The forces which are affecting the machine tool spindle during machining are Tangential force (Fz), Axial force (Fx), radial force (Fy) will be estimated. Based on maximum cutting force incurred the analysis will be carried out. Design calculations are performed for bearing and spindle shaft using Analytical approach for determination of bearing life and the rigidity of the spindle shaft respectively. The spindle is then modeled using Autodesk Inventor modeling software. Finite Element method is used on Spindle shaft, critical and structural components to determine total deformation and von-Mises stress in the components. In Finite Element Method, Static structural analysis is performed to determine stress and total deformation in the components. -

The Design Development of the Sliding Table Saw Towards Improving Its Dynamic Properties

applied sciences Review The Design Development of the Sliding Table Saw Towards Improving Its Dynamic Properties Kazimierz A. Orlowski 1,* , Przemyslaw Dudek 2, Daniel Chuchala 1 , Wojciech Blacharski 1 and Tomasz Przybylinski 3 1 Department of Manufacturing and Production Engineering, Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Gdansk University of Technology, 80-233 Gdansk, Poland; [email protected] (D.C.); [email protected] (W.B.) 2 Rema S.A., 11-440 Reszel, Poland; [email protected] 3 Institute of Fluid-Flow Machinery, Polish Academy of Sciences, 80-233 Gdansk, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 15 September 2020; Accepted: 15 October 2020; Published: 21 October 2020 Abstract: Cutting wood with circular saws is a popular machining operation in the woodworking and furniture industries. In the latter sliding table saws (panel saws) are commonly used for cutting of medium density fiberboards (MDF), high density fiberboards (HDF), laminate veneer lumber (LVL), plywood and chipboards of different structures. The most demanded requirements for machine tools are accuracy and precision, which mainly depend on the static deformation and dynamic behavior of the machine tool under variable cutting forces. The aim of this study is to present a new holistic approach in the process of changing the sliding table saw design solutions in order to obtain a better machine tool that can compete in the contemporary machine tool market. This study presents design variants of saw spindles, the changes that increase the critical speeds of spindles, the measurement results of the dynamic properties of the main drive system, as well as the development of the machine body structure. -

Woodworking Glossary

Woodworking Glossary Abrasives Any substance such as aluminum oxide, silicon carbide, garnet, emery, flint or similar materials that is used to abrade or sand wood, steel or other materials. Substances such as India, Arkansas, crystolon, silicon carbide and waterstones used to sharpen steel edged tools are included. Alternating Grain Direction The process of gluing-up or laminating wood for project components with alternating pieces having the grain running perpendicular to one another (as opposed to parallel). Usually, this practice is enlisted to provide superior strength in a project that is expected to be under stress. It is also used occasionally for decorative purposes. Bevel An angular edge on a piece of stock, usually running from the top or face surface to the adjacent edge or the opposing (bottom) surface. In most cases, bevels are formed for joinery, but are also occasionally used for decorative purposes. Chamfer A slight angular edge that is formed on a piece of stock for decorative purposes or to eliminate sharp corners. Chamfers are similar to bevels but are less pronounced and do not go all the way from one surface to another. Compound Cutting The act of cutting out a project or project component (usually with a bandsaw) to create a three-dimensional or “sculpted” shape. This is accomplished by cutting one profile, taping scraps back in place, and rotating the workpiece to cut a second profile, usually 90° to the first. Compound Miter A combination miter and bevel cut. Generally a compound miter is used in building shadow box picture frames and similar projects where angled or “deep set” project sides are desired. -

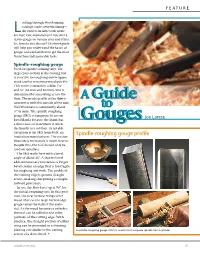

Guide to Gouges

FEATURE ooking through woodturning catalogs can be overwhelming— L the choices in lathe tools alone are vast! One manufacturer lists over a dozen gouges in various sizes and styles. So, how do you choose? This brief guide will help you understand the basics of gouges and explain how to get the most from these indispensable tools. Spindle-roughing gouge Used for spindle turning only. The large cross-section at the cutting end is effective for roughing down square stock and for removing wood quickly. This tool is commonly sold in 1¼" and ¾" (32 mm and 20 mm). Size is determined by measuring across the flute. The inside profile of the flute is A Guide concentric with the outside of the tool. Wall thickness is consistently about to ¼" (6 mm). The spindle-roughing gouge (SRG) is dangerous to use on Joe Larese bowl blanks because the shank has Gouges a thin cross-section where it enters the handle (see sidebar). (A notable exception is the SRG from P&N, an Spindle-roughing gouge profile Australian manufacturer. The section that enters the handle is much heavier. Despite this, the tool should only be used on spindles.) The SRG works best with a bevel angle of about 45°. A shorter bevel adds unnecessary resistance; a longer bevel creates an edge that is too fragile for roughing out work. The profile of the cutting edge is ground straight across, making sharpening a straight- forward procedure. In use, the flute faces up at 90° for the initial roughing cuts. In this posi- tion, the near vertical wings sever wood fibers as the large curved edge gouges away the bulk of the mate- rial.