The Victors in World War I and Finland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Baltic Sea Region the Baltic Sea Region

TTHEHE BBALALTTICIC SSEAEA RREGIONEGION Cultures,Cultures, Politics,Politics, SocietiesSocieties EditorEditor WitoldWitold MaciejewskiMaciejewski A Baltic University Publication Case Chapter 2 Constructing Karelia: Myths and Symbols in the Multiethnic Reality Ilja Solomeshch 1. Power of symbols Specialists in the field of semiotics note that in times of social and political crises, at Political symbolism is known to have three the stage of ideological and moral disintegra- major functions – nominative, informative tion, some forms of the most archaic kinds of and communicative. In this sense a symbol in political symbolism reactivate in what is called political life plays one of the key roles in struc- the archaic syndrome. This notion is used, for turing society, organising interrelations within example, to evaluate the situation in pre- and the community and between people and the post-revolutionary (1917) Russia, as well as various institutions of state. Karelia Karelia is a border area between Finland and Russia. Majority of its territory belongs to Russian Republic of Karelia, with a capital in Petrozavodsk. The Sovjet Union gained the marked area from Finland as the outcome of war 1944. Karelia can be compared with similar border areas in the Baltic Region, like Schleswig-Holstein, Oppeln (Opole) Silesia in Poland, Kaliningrad region in Russia. Probably the best known case of such an area in Europe is Alsace- -Lorraine. Map 13. Karelia. Ill.: Radosław Przebitkowski The Soviet semioticity When trying to understand historical and cultural developments in the Russian/Soviet/Post-Soviet spatial area, especially in terms of Centre-Peripheries and Break-Continuity paradigms, one can easily notice the semioticity of the Soviet system, starting with its ideology. -

Foreign Capital and Finland: Central Government's Firstperiod of Reliance on International Financial Markets 1862-1938

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Arola, Mika Book Foreign capital and Finland: central government's firstperiod of reliance on international financial markets 1862-1938 Scientific monographs, No. E:37 Provided in Cooperation with: Bank of Finland, Helsinki Suggested Citation: Arola, Mika (2006) : Foreign capital and Finland: central government's firstperiod of reliance on international financial markets 1862-1938, Scientific monographs, No. E:37, ISBN 952-462-311-0, Bank of Finland, Helsinki, http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:NBN:fi:bof-201408071697 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/212970 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend -

Finlands Röda Garden En Bok Om Klasskriget 1918 1:A Upplagan Bokförlaget Oktober 1973

Carsten Palmær och Raimo Mankinen Finlands röda garden En bok om klasskriget 1918 1:a upplagan Bokförlaget Oktober 1973 Innehållsförteckning Inledning..................................................................................................................................... 1 DEL 1: DOKUMENT .............................................................................................................. 41 Ur rödgardismen....................................................................................................................... 41 Makten åt arbetarna – proletariatets diktatur måste utropas .................................................... 44 Bakom den vita fronten: Varkaus och Isalmi........................................................................... 47 Den finska arbetarstaten........................................................................................................... 54 Minnen från storstrejken och inbördeskriget 1917-18 ............................................................. 59 Trupper till Tammerfors hjälp.................................................................................................. 63 De bildade en sköld av tillfångatagna rödgardister och arbetare ............................................. 67 Vad arbetarkvinnorna fick erfara ............................................................................................. 70 Minnen från klasskampsfronterna år 1918............................................................................... 72 Det finska röda gardet -

1 Capitalism Under Attack: Economic Elites and Social Movements in Post

Capitalism under attack: Economic elites and social movements in post-war Finland Niklas Jensen-Eriksen Author’s Accepted Manuscript Published as: Jensen-Eriksen N. (2018) Capitalism Under Attack: Economic Elites and Social Movements in Post-War Finland. In: Berger S., Boldorf M. (eds) Social Movements and the Change of Economic Elites in Europe after 1945. Palgrave Studies in the History of Social Movements. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77197-7_11 Introduction For Finland, the post-war era began in September 1944 when it switched sides in the Second World War. The country, which had fought alongside Germany against the Soviet Union from the summer of 1941 onwards, was now left within the Soviet sphere of influence.1 In this altered political situation, new social movements, in particular those led by communists and other leftist activists, challenged the existing economic and political order. However, this article argues that the traditional economic elites were remarkably successful in defending their interests. When the ‘years of danger’, as the period 1944–48 has been called in Finland, ended, it remained a country with traditional Western-style parliamentary democracy and a capitalist economic system. Before the parliamentary elections of 1945, Finnish Prime Minister J.K. Paasikivi, the main architect of the country’s new foreign policy (which was based on the attempt to maintain warm relations with the Soviet Union), urged voters to elect ‘new faces’ to Parliament.2 The voters did so. A new communist-dominated political party, the Finnish People’s Democratic League (Suomen Kansan Demokraattinen Liitto, SKDL) received a quarter of the seats. -

Language Legislation and Identity in Finland Fennoswedes, the Saami and Signers in Finland’S Society

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto UNIVERSITY OF HELSINKI Language Legislation and Identity in Finland Fennoswedes, the Saami and Signers in Finland’s Society Anna Hirvonen 24.4.2017 University of Helsinki Faculty of Law Public International Law Master’s Thesis Advisor: Sahib Singh April 2017 Tiedekunta/Osasto Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty Laitos/Institution– Department Oikeustieteellinen Helsingin yliopisto Tekijä/Författare – Author Anna Inkeri Hirvonen Työn nimi / Arbetets titel – Title Language Legislation and Identity in Finland: Fennoswedes, the Saami and Signers in Finland’s Society Oppiaine /Läroämne – Subject Public International Law Työn laji/Arbetets art – Level Aika/Datum – Month and year Sivumäärä/ Sidoantal – Number of pages Pro-Gradu Huhtikuu 2017 74 Tiivistelmä/Referat – Abstract Finland is known for its language legislation which deals with the right to use one’s own language in courts and with public officials. In order to examine just how well the right to use one’s own language actually manifests in Finnish society, I examined the developments of language related rights internationally and in Europe and how those developments manifested in Finland. I also went over Finland’s linguistic history, seeing the developments that have lead us to today when Finland has three separate language act to deal with three different language situations. I analyzed the relevant legislations and by examining the latest language barometer studies, I wanted to find out what the real situation of these language and their identities are. I was also interested in the overall linguistic situation in Finland, which is affected by rising xenophobia and the issues surrounding the ILO 169. -

RUSSO-FINNISH RELATIONS, 1937-1947 a Thesis Presented To

RUSSO-FINNISH RELATIONS, 1937-1947 A Thesis Presented to the Department of History Carroll College In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Academic Honors with a B.A. Degree In History by Rex Allen Martin April 2, 1973 SIGNATURE PAGE This thesis for honors recognition has been approved for the Department of History. II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to acknowledge thankfully A. Patanen, Attach^ to the Embassy of Finland, and Mrs. Anna-Malja Kurlkka of the Library of Parliament in Helsinki for their aid in locating the documents used In my research. For his aid In obtaining research material, I wish to thank Mr. H. Palmer of the Inter-Library Loan Department of Carroll College. To Mr. Lang and to Dr. Semmens, my thanks for their time and effort. To Father William Greytak, without whose encouragement, guidance, and suggestions this thesis would never have been completed, I express my warmest thanks. Rex A. Martin 111 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... v I. 1937 TO 1939 ........................................................................................ 1 II. 1939 TO1 940.................................................... 31 III. 1940 TO1 941............................................................................................. 49 IV. 1941 TO1 944 ......................................................................................... 70 V. 1944 TO 1947 ........................................................................................ -

WTR 1000 Preview: the Global Legal Powerhouses

Feature By Nicholas Richardson, Mary Hawkins and Simon Messenger WTR 1000 preview: the global legal powerhouses The next edition of the World Trademark Review 1000, owners when selecting legal counsel close to home, as well as in often released in January 2014, comprehensively unfamiliar and challenging jurisdictions. With many brand owners focusing on key regional markets, the identifies the world’s leading trademark firms listings for the 2014 guide have been grouped on a regional basis. In and practitioners. In this preview, exclusive to advance of publication of the 2014 edition, the tables in this article WTR subscribers, we identify the firms which have reveal those firms which have achieved a listing in more than one achieved a listing in more than one region, as well region, as well as those which are home to the largest number of as those which are home to the largest numbers of independently recommended practitioners. The variety of firms included reflects the health of the trademark independently recommended practitioners marketplace and the diverse needs of clients and those law firms referring work onwards. The WTR 1000 is thus an essential guide in strong brand is vital to success in today’s intensely today’s brand-focused economy. competitive and increasingly globalised market. Trademarks are key tools through which businesses Adams & Adams can protect the goodwill and reputation inherent in Recommended in regions: 1 A their brands, and build and maintain demand for Recommended individuals: 8 their products and services. External advisers play a crucial role in developing and implementing brand strategies for both local and South African IP titan Adams & Adams has eight individuals international markets, and in protecting these vital assets in the face recommended in the WTR 1000 2014 – one of the highest numbers of infringement. -

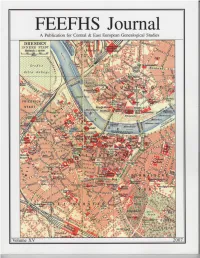

FEEFHS Journal Volume 15, 2007

FEEFHS Journal Volume 15, 2007 FEEFHS Journal Who, What and Why is FEEFHS? The Federation of East European Family History Societies Guest Editor: Kahlile B. Mehr. [email protected] (FEEFHS) was founded in June 1992 by a small dedicated group of Managing Editor: Thomas K. Edlund American and Canadian genealogists with diverse ethnic, religious, and national backgrounds. By the end of that year, eleven societies FEEFHS Executive Council had accepted its concept as founding members. Each year since then FEEFHS has grown in size. FEEFHS now represents nearly two 2006-2007 FEEFHS officers: hundred organizations as members from twenty-four states, five Ca- President: Dave Obee, 4687 Falaise Drive, Victoria, BC V8Y 1B4 nadian provinces, and fourteen countries. It continues to grow. Canada. [email protected] About half of these are genealogy societies, others are multi- 1st Vice-president: Brian J. Lenius. [email protected] purpose societies, surname associations, book or periodical publish- 2nd Vice-president: Lisa A. Alzo ers, archives, libraries, family history centers, online services, insti- 3rd Vice-president: Werner Zoglauer tutions, e-mail genealogy list-servers, heraldry societies, and other Secretary: Kahlile Mehr, 412 South 400 West, Centerville, UT. ethnic, religious, and national groups. FEEFHS includes organiza- [email protected] tions representing all East or Central European groups that have ex- Treasurer: Don Semon. [email protected] isting genealogy societies in North America and a growing group of worldwide organizations and individual members, from novices to Other members of the FEEFHS Executive Council: professionals. Founding Past President: Charles M. Hall, 4874 S. 1710 East, Salt Lake City, UT 84117-5928 Goals and Purposes: Immediate Past President: Irmgard Hein Ellingson, P.O. -

Homelessness 2018

Report 3/2019 Homelessness in 2018 05/03/2019 283 (6 %) 822 ( 17 %) 229 (4 %) Outside, in emergency 381 (8 %) shelters Dormitories In institutions due to a lack of an apartment Temporarily with friends or family No information available on the form of homelessness 3167 ( 65 %) Figure 1. The forms of homelessness for people living alone (n=4,882) in Finland in 2018. Contents Summary .............................................................................................................. 3 1 On the Homelessness in 2018 report ............................................................ 3 2 In 2018, a total of 5,482 homeless people were living in Finland .................. 4 2.1 Helsinki ............................................................................................................. 4 2.2 The rest of Finland, excluding Helsinki ............................................................ 5 2.3 The different forms of homelessness in the whole country ............................. 6 3 Municipalities with the most homelessness in 2018 ...................................... 9 3.1 Comments made by the municipalities on the development of homelessness ............................................................................................ 10 4 Homeless prisoners who are due for release .............................................. 11 5 The results of the homelessness programmes ........................................... 12 6 New guidelines for the compilation of statistics on homelessness .............. 13 Appendix 1 Definitions -

Talviaik Ata Ulut

INKOO – KIRKKONUMMI TH – HELSINKI 018 HELSINKI – KARJAA – TAMMISAARI 018 HELSINKI – KARJAA – FISKARI INGÅ – KYRKSLÄTT VGS – HELSINGFORS 018 HELSINGFORS – KARIS – EKENÄS 018 HELSINGFORS – KARIS – FISKARS Merkkien selitykset – Teckenförklaring: – VINTERTIDTABELLER TALVIAIKATAULUT 018 PIKA 018 018 018 018 018 V M–P M–P M–P M–P Laituri H:ki Laituri H:ki 27 16 16 27 16 26 16 16 27 + Kouluvuoden aikana – Under skolåret Ingå/Inkoo 7,15 ~7,55TH 9,10 15,05 Plattform H:fors M–P M–P M–P Plattform H:fors M–P M–P M–P M–P M–P M–P Helsinki/Helsingfors 9,25 13,25 16,10 Vain koulujen kesäloman aikana Helsinki/Helsingfors 9,25 13,25 14.15 16.10 17,00 18.45 ++ Kyrkslätt VGS/Kirkkonummi TH 7,45 x 9,35 15,30 Lauttasaari/Drumsö - x x Under skolans sommarlov K:nummi/Kyrkslätt th - 13,55 - 16.45 17,35 - Jorvas TH x x x x Jorvas th - x x +++ 1.5–30.9 K:nummi/Kyrkslätt th - 13,55 16,45 Inkoo/Ingå - 14,25 - 17.15 18,05 - Iso Omena x x x x Maanantaista perjantaihin Inkoo kk/Ingå kby - 14,25 17,15 Lohja/Lojo 15.30 - 20.05 M–P Lauttasaari/Drumsö x - x x Karjaa las/Karis busst 11,10 14,50 17,40 Från måndag till fredag Puh./Tfn Karjaa/Karis 11,10 14,40 16.30 17.40 18,30 20.50 E-mail Helsingfors/Helsinki Kamppi 8,20 8,50 10,05 16,00 Karjaa ras/Karis jv.st. I 17,45 Jatkaa tarvittaessa T Fax Tammisaari/Ekenäs 11,35 15,10 18,10 Pohja/Pojo 11,25 15,25 16.45 18,45 21.05 Fortsätter vid behov 2.1.2018 Alkaen / Fr.o.m. -

Työväen Bibliografia 4.Pdf

PEKKA KAARNINEN IT I ** * 1 __ ILKKA LIIKANEN ■ || \ f fr* fj bibliografia IV Tvövfl tNPtfi i NNt^n r b cmfnRnoma w V Pekka Kääminen Ilkka Liikanen Työväen bibliografia IV Suomen työväenliikkeen historiallinen bibliografia Julkaisija TYÖVfltNPtRINNt-flRBCTflfrrfififXriON Paasivuorenkatu S B, 00530 Helsinki Kansi: Mäntän Työväenyhdistyksen lainakirjasto vuodelta 1923 Työväen Arkiston kuvakokoelma Ulkoasu:Markku Böök Helsinki 1994. Hakapaino Oy 411 ffm ' Kierrätykseen sopiva tuote ISSN 0785-2975 Alhaiset päästöt valmistuksessa ISBN 951-96071-3-7 Hakapaino Oy, Helsinki 1994 ESIPUHE KÄYTTÄJÄLLE SISÄLLYSLUETTELO 1. Aatehistoria ja teoreettiset kysymykset 1 2. Kansainvälinen työväenliike ja työväen liike eri maissa 5 3. Suomen pointtien elämä ja poliittinen historia 11 3.1. Valtakunnallinen näkökulma 11 3.2. Paikallinen ja alueellinen näkökulma 79 3.3. Sosiaalidemokraattiset puolueet 107 3.4. Kansandemokraattiset ja kommunis tiset puolueet 138 3.5. Muut työväenpuolueet 157 4. Ammattiyhdistystoiminta 158 4.1. Teollisuuden ja rakennusalan ammat tiliitot 184 4.2. Palvelusalan ammattiliitot 200 4.3. Kuljetusalan ammattiliitot 204 4.4. Julkisen sektorin ammattiliitot 207 4.5. Toimihenkilöiden ja teknisten toimihenkilöiden ammattiliitot 209 4.6. Muut ammattiliitot 211 5. Sivistys ja koulutus 212 5.1. Kulttuuri, harrastukset, työväenperinne 212 5.2. Koulutus. opiskelijaliike, nuoriso järjestöt 238 5.3. Urheilu 253 6. Lehdistö 277 7. Työväestön elämäntapa ja elinolosuhteet 290 8. Henkilöhistoria 293 9. Osuustoiminta, talouselämä, talouspoli tiikka 352 TEKIJÄHAKEMISTO 389 KOHDEHENKILÖHAKEMISTO 405 YHTEISÖHRKEMISTO 407 ASIASANAHAKEMISTO 418 MAANTIETEELLINEN HAKEMISTO 449 KAUSIJULKAISULUETTELO 454 ESIPUHE Työväen bibliografia IV : Suomen työväenliikkeen historiallinen bibliografia jatkaa Työväenperinne - Arbetartradltion ry .-n dokumentointityötä työväenliikettä käsittelevän aineiston kartoittamiseksi ja välittämiseksi tarvitsijoille. Aineisto ulottuu 1800-luvun lopulta nykypäivään ja käsittää yli 4500 viitettä hakemistoineen. -

Jytyn Historiateos (Pdf)

Antti Parpola Neuvotellaan • VUOSISADAN LIITTO • NEUVOTELLAAN Vuosisadan liitto KVL ja Jyty 1918−2018 SISÄLLYS Lukijalle 7 Vaatimukset kasvavat 125 Puheenjohtajan tervehdys 9 Lakkoon 125 Sadan vuoden helminauha 11 Ansiokehitys ylös! 133 Palvelukulttuuriin 135 Osa I Vailla oikeuksia ■ ■ ”Kirkon toiminnalle vieras kylkiäinen” | Puheenjohtaja Taisto Mursula 136, 139 Alussa oli inflaatio 15 Pudotus korkealta 15 Osa III Kun perustukset järkkyvät ■ ■ Puheenjohtaja Harald Dalström | Perustajat 31, 32 Romahdus 145 Pitkä mutta kapea leipä 35 Irtiotto vanhasta 145 ■ ”Att ordna sin ekonomi” 38 Lama ja konkurssi 150 Patriarkaalista edunvalvontaa 42 Uusi alku 155 ■ ■ ■ Puheenjohtaja Zachris Castrén | Avustettuna hautaan | Kansainväliset yhteydet, osa I 47, 48, 51 ■ Puheenjohtaja Katriina Perkka-Jortikka 160 Taistelevan keskusliiton synty 53 Tavoitteena työelämän inhimillistäminen 165 Etujärjestöjen yhteiskunta 53 Työ ja työttömyys 165 ■ ■ Sihteeri Eino Waronen | Puheenjohtaja Knut Furuhjelm 61, 63 ■ Vaikea viestintä, tuloksellinen tutkimus 172 ”Kuinka suuressa kuopassa ollaan?” 65 Toive paremmasta 172 ■ ■ ■ Puheenjohtaja Alex Danielson | Puheenjohtaja Akseli Linnavuori | Pieni kömmähdys 68, 73, 75 Liudentuva kuntasektori 179 Neuvotteluosapuolena 83 Vanha KVL, nuori Jyty 179 Jokavuotinen työtaistelu 83 ■ ■ ■ Järjestäytyneen turva | Puheenjohtaja Markku Jalonen | Strategisesti 180, 184, 185 ■ Puheenjohtaja Eero Rönkä 89 Palvelut, rakenteet ja uudistukset 191 Eheytys ja hajaannus 90 ■ ■ Puheenjohtaja Merja Ailus | Kansainväliset yhteydet, osa II 192,