Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uromacer Catesbyi (Schlegel) 1. Uromacer Catesbyi Catesbyi Schlegel 2. Uromacer Catesbyi Cereolineatus Schwartz 3. Uromacer Cate

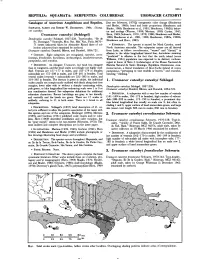

T 356.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SERPENTES: COLUBRIDAE UROMACER CATESBYI Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. [but see Schwartz,' 1970]); ontogenetic color change (Henderson and Binder, 1980); head and body proportions (Henderson and SCHWARTZ,ALBERTANDROBERTW. HENDERSON.1984. Uroma• Binder, 1980; Henderson et a\., 1981; Henderson, 1982b); behav• cer catesbyi. ior and ecology (Werner, 1909; Mertens, 1939; Curtiss, 1947; Uromacer catesbyi (Schlegel) Horn, 1969; Schwartz, 1970, 1979, 1980; Henderson and Binder, 1980; Henderson et a\., 1981, 1982; Henderson, 1982a, 1982b; Dendrophis catesbyi Schlegel, 1837:226. Type-locality, "lie de Henderson and Horn, 1983). St.- Domingue." Syntypes, Mus. Nat. Hist. Nat., Paris, 8670• 71 (sexes unknown) taken by Alexandre Ricord (date of col• • ETYMOLOGY.The species is named for Mark Catesby, noted lection unknown) (not examined by authors). North American naturalist. The subspecies names are all derived Uromacer catesbyi: Dumeril, Bibron, and Dumeril, 1854:72l. from Latin, as follow: cereolineatus, "waxen" and "thread," in allusion to the white longitudinal lateral line; hariolatus meaning • CONTENT.Eight subspecies are recognized, catesbyi, cereo• "predicted" in allusion to the fact that the north island (sensu lineatus,frondicolor, hariolatus, inchausteguii, insulaevaccarum, Williams, 1961) population was expected to be distinct; inchaus• pampineus, and scandax. teguii in honor of Sixto J. Inchaustegui, of the Museo Nacional de • DEFINITION.An elongate Uromacer, but head less elongate Historia Natural de Santo Domingo, Republica Dominicana; insu• than in congeners, and the head scales accordingly not highly mod• laevaccarum, a literal translation of lIe-a-Vache (island of cows), ified. Ventrals are 157-177 in males, and 155-179 in females; pampineus, "pertaining to vine tendrils or leaves;" and scandax, subcaudals are 172-208 in males, and 159-201 in females. -

Zootaxa, Molecular Phylogeny, Classification, and Biogeography Of

Zootaxa 2067: 1–28 (2009) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2009 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Molecular phylogeny, classification, and biogeography of West Indian racer snakes of the Tribe Alsophiini (Squamata, Dipsadidae, Xenodontinae) S. BLAIR HEDGES1, ARNAUD COULOUX2, & NICOLAS VIDAL3,4 1Department of Biology, 208 Mueller Lab, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802-5301 USA. E-mail: [email protected] 2Genoscope. Centre National de Séquençage, 2 rue Gaston Crémieux, CP5706, 91057 Evry Cedex, France www.genoscope.fr 3UMR 7138, Département Systématique et Evolution, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, CP 26, 57 rue Cuvier, 75005 Paris, France 4Corresponding author. E-mail : [email protected] Abstract Most West Indian snakes of the family Dipsadidae belong to the Subfamily Xenodontinae and Tribe Alsophiini. As recognized here, alsophiine snakes are exclusively West Indian and comprise 43 species distributed throughout the region. These snakes are slender and typically fast-moving (active foraging), diurnal species often called racers. For the last four decades, their classification into six genera was based on a study utilizing hemipenial and external morphology and which concluded that their biogeographic history involved multiple colonizations from the mainland. Although subsequent studies have mostly disagreed with that phylogeny and taxonomy, no major changes in the classification have been proposed until now. Here we present a DNA sequence analysis of five mitochondrial genes and one nuclear gene in 35 species and subspecies of alsophiines. Our results are more consistent with geography than previous classifications based on morphology, and support a reclassification of the species of alsophiines into seven named and three new genera: Alsophis Fitzinger (Lesser Antilles), Arrhyton Günther (Cuba), Borikenophis Hedges & Vidal gen. -

Ecological Functions of Neotropical Amphibians and Reptiles: a Review

Univ. Sci. 2015, Vol. 20 (2): 229-245 doi: 10.11144/Javeriana.SC20-2.efna Freely available on line REVIEW ARTICLE Ecological functions of neotropical amphibians and reptiles: a review Cortés-Gomez AM1, Ruiz-Agudelo CA2 , Valencia-Aguilar A3, Ladle RJ4 Abstract Amphibians and reptiles (herps) are the most abundant and diverse vertebrate taxa in tropical ecosystems. Nevertheless, little is known about their role in maintaining and regulating ecosystem functions and, by extension, their potential value for supporting ecosystem services. Here, we review research on the ecological functions of Neotropical herps, in different sources (the bibliographic databases, book chapters, etc.). A total of 167 Neotropical herpetology studies published over the last four decades (1970 to 2014) were reviewed, providing information on more than 100 species that contribute to at least five categories of ecological functions: i) nutrient cycling; ii) bioturbation; iii) pollination; iv) seed dispersal, and; v) energy flow through ecosystems. We emphasize the need to expand the knowledge about ecological functions in Neotropical ecosystems and the mechanisms behind these, through the study of functional traits and analysis of ecological processes. Many of these functions provide key ecosystem services, such as biological pest control, seed dispersal and water quality. By knowing and understanding the functions that perform the herps in ecosystems, management plans for cultural landscapes, restoration or recovery projects of landscapes that involve aquatic and terrestrial systems, development of comprehensive plans and detailed conservation of species and ecosystems may be structured in a more appropriate way. Besides information gaps identified in this review, this contribution explores these issues in terms of better understanding of key questions in the study of ecosystem services and biodiversity and, also, of how these services are generated. -

Recommendations for Tourism and Biodiversity Conservation at Laguna Bavaro Wildlife Refuge, Dominican Republic

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR TOURISM AND BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION AT LAGUNA BAVARO WILDLIFE REFUGE, DOMINICAN REPUBLIC June 2011 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared in cooperation with US Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry, USAID and the Ornithological Society of Hispaniola (SOH) technical staff, and partners. Bibliographic Citation Bauer, Jerry, Jorge Brocca and Jerry Wylie. 2011. Recommendations for Tourism and Biodiversity Conservation at Laguna Bavaro Wildlife Refuge Dominican Republic. Report prepared by the US Forest Service International Institute of Tropical Forestry for the USAID/Dominican Republic in support of the Dominican Sustainable Tourism Alliance. Credits Photographs: Jerry Wylie, Jerry Bauer, Waldemar Alcobas and Jorge Brocca Graphic Design: Liliana Peralta Lopez TECHNICAL REPORT RECOMMENDATIONS FOR TOURISM AND BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION AT LAGUNA BAVARO WILDLIFE REFUGE, DOMINICAN REPUBLIC Jerry Bauer Biological Scientist US Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry Jorge Brocca Executive Director Ornithological Society of Hispaniola and Jerry Wylie Ecotourism Specialist US Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry In cooperation with Dominican Sustainable Tourism Alliance La Altagracia Tourism Cluster Fundación Ecologica y Social Natura Park, Inc. June 2011 Sociedad Ornitológica de la Hispaniola SOH This work was completed with support from the people of the United States through USAID/Dominican Republic by the USDA Forest Service International Institute of Tropical Forestry under PAPA No. AEG-T-00-07-00003-00, TASK #7 (Sustainable Tourism Support) and the Ornithological Society of Hispaniola (SOH) in partnership with La Altagracia Tourism Cluster and assistance from local and international partners and collaborators. DISCLAIMER The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. -

Revisión Periódica De Reservas De La Biosfera

2 REVISIÓN PERIÓDICA DE RESERVAS DE LA BIOSFERA [Enero de 2013] INTRODUCCIÓN La Conferencia General de la UNESCO, en su 28ª sesión, adoptó la Resolución 28 C/2.4 en el Marco Estatutario de la Red Mundial de Reservas de la Biosfera. Este texto define en particular, los criterios para que un área esté cualificada para ser designada como reserva de la biosfera (Artículo 4). Además, el Artículo 9 contempla una revisión periódica cada 10 años, que consiste en un informe que debe preparar la autoridad competente, en base a los criterios del Artículo 4 y enviarlo al secretariado del Estado correspondiente. El texto del Marco Estatutario se recoge en el tercer anexo. El formulario que se facilita a continuación sirve para ayudar a los Estados a preparar su informe nacional, de acuerdo con el Artículo 9, y para actualizar en la Secretaria los datos disponibles de la reserva de la biosfera correspondiente. Este informe deber permitir al Consejo Internacional de Coordinación (CIC) del Programa MAB, revisar cómo cada reserva de la biosfera está cumpliendo con los criterios del Artículo 4 del Marco Estatutario y en particular con las tres funciones. Cabe señalar que en la última parte del formulario (Criterios y Avances Logrados), se pide que se indique cómo las reservas de la biosfera cumplen con cada uno de estos criterios. La UNESCO utilizará de diversas maneras la información presentada en esta revisión periódica: (a) para la evaluación de la reserva de la biosfera por parte del Comité Consultivo Internacional de las Reservas de Biosfera y por la Mesa del Consejo Internacional de Coordinación del MAB; (b) para utilizarla en un sistema de información accesible a nivel mundial, en particular la red UNESCO-MAB y publicaciones, facilitando así la comunicación y la interacción entre personas interesadas en las reservas de la biosfera en todo el mundo. -

Baseline Ecological Inventory for Three Bays National Park, Haiti OCTOBER 2016

Baseline Ecological Inventory for Three Bays National Park, Haiti OCTOBER 2016 Report for the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) 1 To cite this report: Kramer, P, M Atis, S Schill, SM Williams, E Freid, G Moore, JC Martinez-Sanchez, F Benjamin, LS Cyprien, JR Alexis, R Grizzle, K Ward, K Marks, D Grenda (2016) Baseline Ecological Inventory for Three Bays National Park, Haiti. The Nature Conservancy: Report to the Inter-American Development Bank. Pp.1-180 Editors: Rumya Sundaram and Stacey Williams Cooperating Partners: Campus Roi Henri Christophe de Limonade Contributing Authors: Philip Kramer – Senior Scientist (Maxene Atis, Steve Schill) The Nature Conservancy Stacey Williams – Marine Invertebrates and Fish Institute for Socio-Ecological Research, Inc. Ken Marks – Marine Fish Atlantic and Gulf Rapid Reef Assessment (AGRRA) Dave Grenda – Marine Fish Tampa Bay Aquarium Ethan Freid – Terrestrial Vegetation Leon Levy Native Plant Preserve-Bahamas National Trust Gregg Moore – Mangroves and Wetlands University of New Hampshire Raymond Grizzle – Freshwater Fish and Invertebrates (Krystin Ward) University of New Hampshire Juan Carlos Martinez-Sanchez – Terrestrial Mammals, Birds, Reptiles and Amphibians (Françoise Benjamin, Landy Sabrina Cyprien, Jean Roudy Alexis) Vermont Center for Ecostudies 2 Acknowledgements This project was conducted in northeast Haiti, at Three Bays National Park, specifically in the coastal zones of three communes, Fort Liberté, Caracol, and Limonade, including Lagon aux Boeufs. Some government departments, agencies, local organizations and communities, and individuals contributed to the project through financial, intellectual, and logistical support. On behalf of TNC, we would like to express our sincere thanks to all of them. First, we would like to extend our gratitude to the Government of Haiti through the National Protected Areas Agency (ANAP) of the Ministry of Environment, and particularly Minister Dominique Pierre, Ministre Dieuseul Simon Desras, Mr. -

A Phylogeny and Revised Classification of Squamata, Including 4161 Species of Lizards and Snakes

BMC Evolutionary Biology This Provisional PDF corresponds to the article as it appeared upon acceptance. Fully formatted PDF and full text (HTML) versions will be made available soon. A phylogeny and revised classification of Squamata, including 4161 species of lizards and snakes BMC Evolutionary Biology 2013, 13:93 doi:10.1186/1471-2148-13-93 Robert Alexander Pyron ([email protected]) Frank T Burbrink ([email protected]) John J Wiens ([email protected]) ISSN 1471-2148 Article type Research article Submission date 30 January 2013 Acceptance date 19 March 2013 Publication date 29 April 2013 Article URL http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/13/93 Like all articles in BMC journals, this peer-reviewed article can be downloaded, printed and distributed freely for any purposes (see copyright notice below). Articles in BMC journals are listed in PubMed and archived at PubMed Central. For information about publishing your research in BMC journals or any BioMed Central journal, go to http://www.biomedcentral.com/info/authors/ © 2013 Pyron et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. A phylogeny and revised classification of Squamata, including 4161 species of lizards and snakes Robert Alexander Pyron 1* * Corresponding author Email: [email protected] Frank T Burbrink 2,3 Email: [email protected] John J Wiens 4 Email: [email protected] 1 Department of Biological Sciences, The George Washington University, 2023 G St. -

Further Analysis and a Reply

Herpetologica, 58(2), 2002, 270-275 ? 2002 by The Herpetologists'League, Inc. SNAKE RELATIONSHIPS REVEALED BY SLOWLY-EVOLVING PROTEINS: FURTHER ANALYSIS AND A REPLY RICHARD HIGHTON', S. BLAIR HEDGES2, CARLA ANN HASS2, AND HERNDON G. DOWLING3 'Department of Biology, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742, USA 2Department of Biology, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802, USA 3Rendalia Biologists, 1811 Rendalia Motorway, Talladega, AL 35160, USA ABSTRACT: A reanalysis of our allozyme data (Dowling et al., 1996) for four slowly-evolving loci in 215 species of snakes by Buckley et al. (2000) concluded that because of ties in genetic distances our published UPGMA tree had "little resolution, indicating that these data are highly ambiguous regarding higher-level snake phylogeny." They also concluded that "the high degree of resolution in the published phenogram is an analytical artifact." Our study was intended to obtain information on lower-level relationships for the snake species that we had available, and it provided support for some current hypotheses of snake relationships at that level. Buckley et al. (2000) reached their conclusions because in their analysis they used only strict consensus trees and did not randomize the order of their input data. By randomizing data input order and using a majority-rule consensus tree, we show that there is considerable phylogenetic signal in our data. Key words: Allozymes; Genetic distances; Phylogeny; Serpentes; UPGMA trees FIVE years ago, we published an allo- tle phylogenetic signal in our data set. zyme study of 215 species of snakes, about Thus, they claimed that the allozyme data 8% of living species (Dowling et al., 1996). -

Memoirs of the Museum of Comparative Zoölogy, at Harvard

v^^<^^u^ /IDemotrs of tbe /IDuseum of Comparative 2;oologs AT HARVARD COLLEGE. Vol. XLIV. No. 2. A CONTRIBUTION TO THE ZOOGEOGKAPHY OF THE WEST INDIES, WITH ESPECIAL KEFERENCE TO AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES. BY THOMAS BARBOUR. WITH ONE PLATE. CAMBRIDGE, U.S.A.: printed foe tbe rtDuseum. March, 1914. /iDemotrs of tbe flDuseum of Comparattve Zoology AT HARVARD COLLEGE. Vol. XLIV. No. 2. A CONTRIBUTION TO THE ZOOGEOGRArHY OF THE WEST INDIES, WITH ESPECIAL REFERENCE TO AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES. BY THOMAS BARBOUR. WITH ONE PLATE. CAMBRIDGE, U.S.A.: prlnteJ) for tbe /IDuseum. March, 1914. TABLE OF CONTENTS. Page. INTRODUCTION ' 209 Note 213 LIST OF SPECIES INCORRECTLY RECORDED FROM THE WEST INDIES 217 INTRODUCED SPECIES {Fortuitously or otherwise) 220 ZOOGEOGRAPHY 224 Cuba 224 Jamaica 227 Haiti and San Domingo . 227 Porto Rico 228 The Virgin Islands 229 The Lesser Antilles 230 Grenada 230 CONCLUSIONS 236 ANNOTATED LIST OF THE SPECIES 238 TABLE OF DISTRIBUTION 347 PLATE A CONTRIBUTION TO THE ZOOGEOGRArilY OF THE WEST INDIES, WITH ESPECIAL REFERENCE TO AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES. INTRODUCTION. Since its earliest years the Museum of Comparative Zoology has received many collections representing the fauna of the West Indian Islands. To men- tion a few of these, Louis Agassiz and the other scientists on the Hassler col- lected at St. Thomas, on their memorable voyage; and later — from 1877 to 1880 — the Blake visited very many of the islands. The opportunity to col- lect upon all of them was eagei'ly grasped by Mr. Samuel Garman, who was Assistant Naturalist on the Blake during part of the time that she was in charge of Alexander Agassiz. -

Snake Relationships Revealed by Slow-Evolving Proteins: a Preliminary Survey

J. Zool., Lond. (1996) 240, 1-28 Snake relationships revealed by slow-evolving proteins: a preliminary survey 2 3 2 3 H. G. DOWLING. I C. A. HASS. S. BLAIR HEDGES . AND R. HIGHTON 2 IRendalia Biologists, Talladega, Alabama, 35160, USA 2Department o.f Zoology. University of Maryland. College Park. Maryland. 20742. USA (Accepted 22 June 1995) (With 6 figures in the text) We present an initial evaluation of relationships among a diverse sample of 215 species of snakes (8% of the world snake fauna) representing nine ofthe 16 commonly-recognized families. Allelic variation at four slow-evolving. protein-coding loci. detected by starch-gel electrophoresis. was found to be informative for estimating relationships among these species at several levels. The numerous alleles detected at these loci [Acp-2 (42 alleles). Ldh-2 (43). Mdh-I (29). Pgm (25)] provided unexpected clarity in partitioning these taxa. Most congeneric species and several closely-related genera have the same allele at all four loci or differ at only a single locus. At the other extreme are those species with three or four unique alleles: these taxa cannot be placed in this analysis. Species sharing two or three distinctive alleles are those most clearly separated into clades. Typhlopids. pythonids. viperids. and elapids were resolved into individual clades, whereas boids were separated into boines and erycines, and colubrids appeared as several distinct clades (colubrines. natricines. psammophines, homalopsines, and xenodontines). Viper ids were recognized as a major division containing three separate clades: Asian and American crotalines, Palaearctic and Oriental viperines, and Ethiopian causines. The typhlopids were found to be the basal clade. -

Ahaetulla, Oxybelis, Thelototnis, Uromacer

~rnrnij~~llirnij~rnrn~ ~rn ~~rn~rn~~ rnrn~ rnrnrn~rn~~ Number 37 November 20, 1980 The Ecology and Behavior of Vine Snakes (Ahaetulla; Oxybelis, Thelotornis, Uromacer): A Review Robert W. Henderson and Mary H. Binder REVIEW COMMITTEE FOR THIS PUBLICATION: Gordon Burghardt, University of Tennessee Harry W. Greene, University of California John D. Groves, Philadelphia Zoological Garden ISBN 0-89326-063-0 Milwaukee Public Museum Press Published by the Order of the Board of Trustees Milwaukee Public Museum Accepted for Publication November 20, 1980 The Ecology and Behavior of Vine Snakes (Ahaetulla, Oxybelis, Thelotomis, Uromacer): A Review* Robert W. Henderson and Mary H. Binder • Dedicated to Dr. Henry S. Fitch Abstract: Vine snakes are members of four distantly related genera (Ahaetulla, Oxybelis, Thelotornis and Uromacer) and, as a group, are morphologically, ecologically and behaviorally unique. They are characterized by having a (I) head length/snout length ratio of < 3.0, (2) a snout base width/snout anterior width ratio> 1.76 and (3) a head length/eye diameter ratio > 6.0. They show significant differences (P < .05) from every other group they were tested against for at least two (#1 and #2) of the three ratios, and they differed from other arboreal lizard predators for all three characters. A haetulla prasina and three species of Oxybelis show no onotogenetic change for ratios #1 and #2, but all did for ratio #3. All vine snakes are primarily arboreal, diurnal and feed on active prey-usually lizards. They may very well be the only arboreal snakes that routinely feed on potentially fast moving prey and they are visu- ally oriented predators cued by prey movement. -

Field Observations on the Behavioral Ecology of the Madagascan Leaf-Nosed Snake, Langaha Madagascariensis

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 7(3):442−448. Submitted: 30 June 2012; Accepted: 7 November 2012; Published: 31 December 2012. FIELD OBSERVATIONS ON THE BEHAVIORAL ECOLOGY OF THE MADAGASCAN LEAF-NOSED SNAKE, LANGAHA MADAGASCARIENSIS JESSICA L. TINGLE Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, 14853, USA e-mail: [email protected] Abstract.—Langaha madagascariensis is a vinesnake endemic to Madagascar. Although it was first described in 1790, few publications document the ecology or behavior of the species, and none does so for animals in the wild. This vinesnake is unique in displaying high levels of sexual dimorphism and its possession of an elongated nasal appendage, the function of which is not yet understood. The purpose of this study was to obtain information on the natural history of the snake via observations on free-living specimens. The study took place in the quickly disappearing littoral forest of southern Madagascar. I observed six adult males, but found no females. Observations from this study help to elucidate foraging and feeding behavior and activity patterns in L. madagascariensis. With respect to foraging behavior, the vinesnake proved largely to be a sit and wait predator, although it actively pursued prey on some occasions. Contrary to expectations, it consumed both arboreal and terrestrial lizards. One male I observed for several days and nights demonstrated an interesting behavior whereby each night he returned to the same branch and hung from it pointing straight downwards until the morning. These observations help shed light on a little-studied snake that faces high levels of habitat loss.