Final Report of the Macaya Biosphere Reserve Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uromacer Catesbyi (Schlegel) 1. Uromacer Catesbyi Catesbyi Schlegel 2. Uromacer Catesbyi Cereolineatus Schwartz 3. Uromacer Cate

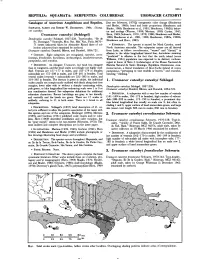

T 356.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SERPENTES: COLUBRIDAE UROMACER CATESBYI Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. [but see Schwartz,' 1970]); ontogenetic color change (Henderson and Binder, 1980); head and body proportions (Henderson and SCHWARTZ,ALBERTANDROBERTW. HENDERSON.1984. Uroma• Binder, 1980; Henderson et a\., 1981; Henderson, 1982b); behav• cer catesbyi. ior and ecology (Werner, 1909; Mertens, 1939; Curtiss, 1947; Uromacer catesbyi (Schlegel) Horn, 1969; Schwartz, 1970, 1979, 1980; Henderson and Binder, 1980; Henderson et a\., 1981, 1982; Henderson, 1982a, 1982b; Dendrophis catesbyi Schlegel, 1837:226. Type-locality, "lie de Henderson and Horn, 1983). St.- Domingue." Syntypes, Mus. Nat. Hist. Nat., Paris, 8670• 71 (sexes unknown) taken by Alexandre Ricord (date of col• • ETYMOLOGY.The species is named for Mark Catesby, noted lection unknown) (not examined by authors). North American naturalist. The subspecies names are all derived Uromacer catesbyi: Dumeril, Bibron, and Dumeril, 1854:72l. from Latin, as follow: cereolineatus, "waxen" and "thread," in allusion to the white longitudinal lateral line; hariolatus meaning • CONTENT.Eight subspecies are recognized, catesbyi, cereo• "predicted" in allusion to the fact that the north island (sensu lineatus,frondicolor, hariolatus, inchausteguii, insulaevaccarum, Williams, 1961) population was expected to be distinct; inchaus• pampineus, and scandax. teguii in honor of Sixto J. Inchaustegui, of the Museo Nacional de • DEFINITION.An elongate Uromacer, but head less elongate Historia Natural de Santo Domingo, Republica Dominicana; insu• than in congeners, and the head scales accordingly not highly mod• laevaccarum, a literal translation of lIe-a-Vache (island of cows), ified. Ventrals are 157-177 in males, and 155-179 in females; pampineus, "pertaining to vine tendrils or leaves;" and scandax, subcaudals are 172-208 in males, and 159-201 in females. -

Zootaxa, Molecular Phylogeny, Classification, and Biogeography Of

Zootaxa 2067: 1–28 (2009) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2009 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Molecular phylogeny, classification, and biogeography of West Indian racer snakes of the Tribe Alsophiini (Squamata, Dipsadidae, Xenodontinae) S. BLAIR HEDGES1, ARNAUD COULOUX2, & NICOLAS VIDAL3,4 1Department of Biology, 208 Mueller Lab, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802-5301 USA. E-mail: [email protected] 2Genoscope. Centre National de Séquençage, 2 rue Gaston Crémieux, CP5706, 91057 Evry Cedex, France www.genoscope.fr 3UMR 7138, Département Systématique et Evolution, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, CP 26, 57 rue Cuvier, 75005 Paris, France 4Corresponding author. E-mail : [email protected] Abstract Most West Indian snakes of the family Dipsadidae belong to the Subfamily Xenodontinae and Tribe Alsophiini. As recognized here, alsophiine snakes are exclusively West Indian and comprise 43 species distributed throughout the region. These snakes are slender and typically fast-moving (active foraging), diurnal species often called racers. For the last four decades, their classification into six genera was based on a study utilizing hemipenial and external morphology and which concluded that their biogeographic history involved multiple colonizations from the mainland. Although subsequent studies have mostly disagreed with that phylogeny and taxonomy, no major changes in the classification have been proposed until now. Here we present a DNA sequence analysis of five mitochondrial genes and one nuclear gene in 35 species and subspecies of alsophiines. Our results are more consistent with geography than previous classifications based on morphology, and support a reclassification of the species of alsophiines into seven named and three new genera: Alsophis Fitzinger (Lesser Antilles), Arrhyton Günther (Cuba), Borikenophis Hedges & Vidal gen. -

Observation of Geophagy by Hispaniolan Crossbill (Loxia Megaplaga) at an Abandoned Bauxite Mine

J. Carib. Ornithol. 25:98–101, 2012 OBSERVATION OF GEOPHAGY BY HISPANIOLAN CROSSBILL (LOXIA MEGAPLAGA) AT AN ABANDONED BAUXITE MINE STEVEN C. LATTA The National Aviary, Allegheny Commons West, Pittsburgh, PA 15212; email: [email protected] Abstract: I report an observation of endangered Hispaniolan Crossbill (Loxia megaplaga) feeding on soils near abandoned bauxite mines in the Sierra de Bahoruco, Dominican Republic. Although geophagy has been widely re- ported from a number of bird taxa, especially Neotropical parrots and boreal carduelines, this is the first report of this behavior from birds in the Caribbean. Based on the known ecology of this crossbill and published reports of local soil characteristics, I suggest testable hypotheses on why soils may be ingested by this species, including the crossbills’ need for dietary salts and their need to detoxify the pine seeds which are their main diet items. Key words: calcium, crossbills, diet, geophagy, Hispaniola, Loxia megaplaga, soil, toxicity Resumen: OBSERVACIÓN DE GEOFAGIA EN LOXIA MEGAPLAGA EN UNA MINA DE BAUXITA ABANDONADA. Observé a Loxia megaplaga, especie amenazada de La Española, alimentándose de barro cerca de minas de bauxita abando- nadas en la Sierra de Bahoruco, República Dominicana. Aunque la geofagia ha sido registrada ampliamente en nu- merosos taxones de aves, especialmente en loros y carduelínidos boreales, este es el primer registro de esta conducta en el Caribe. Basado en el conocimiento de la ecología de esta especie y en los registros publicados sobre las carac- terísticas de los suelos locales, sugiero una hipótesis comprobable de por qué ingieren barro estas especies que inclu- ye la necesidad de suplementos de sales y de detoxificar las semillas de pino que constituyen el principal artículo de su dieta. -

DETERMINATION of the AGE of PINUS OCCIDENTALIS in LA CELESTINA, DOMINICAN REPUBLIC, by the USE of GROWTH RINGS Xander M. Van

IAWA Journal,VoI.18(2), 1997: 139-146 DETERMINATION OF THE AGE OF PINUS OCCIDENTALIS IN LA CELESTINA, DOMINICAN REPUBLIC, BY THE USE OF GROWTH RINGS by Xander M. van der Burgt I Instituto Superior de Agricultura, Apartado 166, Santiago, Republica Dominicana SUMMARY The growth rings of Pinus occidentalis Swartz trees in La Celestina, Dominican Republic, show between-tree uniformity. With difficulty, two mean time series were made from ring widths of 1) all visible, includ ing intra-annual, rings and 2) groups of rings that were hypothesized to be annual. Both were compared with a 63-year range of rainfall data. An annual periodicity in wood formation is present, but obscured by many intra-annual rings. The annual periodicity of the trees may be a remnant of their possible origin from higher altitudes, where frosts may occur during the cold season. The youngest of the 7 investigated trees was about 39 years old; the oldest about 46 years. These seven trees contain be tween approximately 2 and 6 growth rings per year, with an average of about 3.5-4. Key words: Tropical trees, Pinus occidentalis, growth periodicity, rainfall, annual growth, intra-annual rings. INTRODUCTION The forestry and rural development project La Celestina is situated near San Jose de las Matas in the Dominican Republic. In La Celestina the only legal sawmill of the country can be found, surrounded by Pinus occidentalis forests. The exact age of the pine trees is unknown, because the forests were surveyed for the first time in 1980 (Plan Sierra 1991). For the benefit of a sustainable management of these forests it is crucial to know the age of the trees. -

Revisión Periódica De Reservas De La Biosfera

2 REVISIÓN PERIÓDICA DE RESERVAS DE LA BIOSFERA [Enero de 2013] INTRODUCCIÓN La Conferencia General de la UNESCO, en su 28ª sesión, adoptó la Resolución 28 C/2.4 en el Marco Estatutario de la Red Mundial de Reservas de la Biosfera. Este texto define en particular, los criterios para que un área esté cualificada para ser designada como reserva de la biosfera (Artículo 4). Además, el Artículo 9 contempla una revisión periódica cada 10 años, que consiste en un informe que debe preparar la autoridad competente, en base a los criterios del Artículo 4 y enviarlo al secretariado del Estado correspondiente. El texto del Marco Estatutario se recoge en el tercer anexo. El formulario que se facilita a continuación sirve para ayudar a los Estados a preparar su informe nacional, de acuerdo con el Artículo 9, y para actualizar en la Secretaria los datos disponibles de la reserva de la biosfera correspondiente. Este informe deber permitir al Consejo Internacional de Coordinación (CIC) del Programa MAB, revisar cómo cada reserva de la biosfera está cumpliendo con los criterios del Artículo 4 del Marco Estatutario y en particular con las tres funciones. Cabe señalar que en la última parte del formulario (Criterios y Avances Logrados), se pide que se indique cómo las reservas de la biosfera cumplen con cada uno de estos criterios. La UNESCO utilizará de diversas maneras la información presentada en esta revisión periódica: (a) para la evaluación de la reserva de la biosfera por parte del Comité Consultivo Internacional de las Reservas de Biosfera y por la Mesa del Consejo Internacional de Coordinación del MAB; (b) para utilizarla en un sistema de información accesible a nivel mundial, en particular la red UNESCO-MAB y publicaciones, facilitando así la comunicación y la interacción entre personas interesadas en las reservas de la biosfera en todo el mundo. -

Texto Completo (Pdf)

CARACTERIZACIÓN DE LA MORFOLOGÍA DE LA SEMILLA DE PINUS OCCIDENTALIS SWARTZ Morphology characterization of Pinus occidentalis Swartz seeds Virgilio Antonio Miniño Mejía Luis Enrique Rodríguez de Francisco Omar Paino Perdomo Yolanda León * Liz Paulino Resumen: La gran biodiversidad de especies de plantas en la isla La Española, hace conveniente la elaboración de trabajos que permitan identificar las familias, géneros y especies, a partir de diversos caracteres, como los anatómicos. En la República Dominicana se carece de investigaciones sobre las semillas de las especies endémicas. Es importante profundizar en estudios morfológicos y anatómicos de las semillas de nuestras especies y emplearlas con diferentes fines, como orientación taxonómica, conocer más sobre su ecología, entre otros. En nuestro trabajo tratamos de utilizar un carácter relevante de Pinus occidentalis, como es su semilla. El presente estudio nos permite conocer sobre la superficie de la semilla de Pinus occidentalis, pues la morfología de la semilla juega un papel importante en la dispersión de la especie. Palabras clave: Biodiversidad, especies, Pinus occidentalis, morfología, semilla. * Todos los autores son docentes e investigadores del Instituto Tecnológico de Santo Domingo (INTEC). Ciencia y Sociedad 2014; 39(4): 777-801 777 Virgilio Antonio Miniño Mejía, Luis Enrique Rodríguez de Francisco, Omar Paino Perdomo, Yolanda León, Liz Paulino Abstract: The rich biodiversity of plant species on the Hispaniola Island of makes has an advantage on the elaboration of projects to identify families, genera and species, from various characters, such as anatomical. The Dominican Republic lacks research on the seeds of endemic species. It is important to look into mor- phological and anatomical studies of the seeds of our species and use them for different purposes, such as taxonomic orientation, learn more about their ecology, among other purposes. -

A Phylogeny and Revised Classification of Squamata, Including 4161 Species of Lizards and Snakes

BMC Evolutionary Biology This Provisional PDF corresponds to the article as it appeared upon acceptance. Fully formatted PDF and full text (HTML) versions will be made available soon. A phylogeny and revised classification of Squamata, including 4161 species of lizards and snakes BMC Evolutionary Biology 2013, 13:93 doi:10.1186/1471-2148-13-93 Robert Alexander Pyron ([email protected]) Frank T Burbrink ([email protected]) John J Wiens ([email protected]) ISSN 1471-2148 Article type Research article Submission date 30 January 2013 Acceptance date 19 March 2013 Publication date 29 April 2013 Article URL http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/13/93 Like all articles in BMC journals, this peer-reviewed article can be downloaded, printed and distributed freely for any purposes (see copyright notice below). Articles in BMC journals are listed in PubMed and archived at PubMed Central. For information about publishing your research in BMC journals or any BioMed Central journal, go to http://www.biomedcentral.com/info/authors/ © 2013 Pyron et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. A phylogeny and revised classification of Squamata, including 4161 species of lizards and snakes Robert Alexander Pyron 1* * Corresponding author Email: [email protected] Frank T Burbrink 2,3 Email: [email protected] John J Wiens 4 Email: [email protected] 1 Department of Biological Sciences, The George Washington University, 2023 G St. -

Mistletoes of North American Conifers

United States Department of Agriculture Mistletoes of North Forest Service Rocky Mountain Research Station American Conifers General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-98 September 2002 Canadian Forest Service Department of Natural Resources Canada Sanidad Forestal SEMARNAT Mexico Abstract _________________________________________________________ Geils, Brian W.; Cibrián Tovar, Jose; Moody, Benjamin, tech. coords. 2002. Mistletoes of North American Conifers. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS–GTR–98. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 123 p. Mistletoes of the families Loranthaceae and Viscaceae are the most important vascular plant parasites of conifers in Canada, the United States, and Mexico. Species of the genera Psittacanthus, Phoradendron, and Arceuthobium cause the greatest economic and ecological impacts. These shrubby, aerial parasites produce either showy or cryptic flowers; they are dispersed by birds or explosive fruits. Mistletoes are obligate parasites, dependent on their host for water, nutrients, and some or most of their carbohydrates. Pathogenic effects on the host include deformation of the infected stem, growth loss, increased susceptibility to other disease agents or insects, and reduced longevity. The presence of mistletoe plants, and the brooms and tree mortality caused by them, have significant ecological and economic effects in heavily infested forest stands and recreation areas. These effects may be either beneficial or detrimental depending on management objectives. Assessment concepts and procedures are available. Biological, chemical, and cultural control methods exist and are being developed to better manage mistletoe populations for resource protection and production. Keywords: leafy mistletoe, true mistletoe, dwarf mistletoe, forest pathology, life history, silviculture, forest management Technical Coordinators_______________________________ Brian W. Geils is a Research Plant Pathologist with the Rocky Mountain Research Station in Flagstaff, AZ. -

Further Analysis and a Reply

Herpetologica, 58(2), 2002, 270-275 ? 2002 by The Herpetologists'League, Inc. SNAKE RELATIONSHIPS REVEALED BY SLOWLY-EVOLVING PROTEINS: FURTHER ANALYSIS AND A REPLY RICHARD HIGHTON', S. BLAIR HEDGES2, CARLA ANN HASS2, AND HERNDON G. DOWLING3 'Department of Biology, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742, USA 2Department of Biology, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802, USA 3Rendalia Biologists, 1811 Rendalia Motorway, Talladega, AL 35160, USA ABSTRACT: A reanalysis of our allozyme data (Dowling et al., 1996) for four slowly-evolving loci in 215 species of snakes by Buckley et al. (2000) concluded that because of ties in genetic distances our published UPGMA tree had "little resolution, indicating that these data are highly ambiguous regarding higher-level snake phylogeny." They also concluded that "the high degree of resolution in the published phenogram is an analytical artifact." Our study was intended to obtain information on lower-level relationships for the snake species that we had available, and it provided support for some current hypotheses of snake relationships at that level. Buckley et al. (2000) reached their conclusions because in their analysis they used only strict consensus trees and did not randomize the order of their input data. By randomizing data input order and using a majority-rule consensus tree, we show that there is considerable phylogenetic signal in our data. Key words: Allozymes; Genetic distances; Phylogeny; Serpentes; UPGMA trees FIVE years ago, we published an allo- tle phylogenetic signal in our data set. zyme study of 215 species of snakes, about Thus, they claimed that the allozyme data 8% of living species (Dowling et al., 1996). -

Parc National La Visite, Haiti: a Last Refuge for the Country’S Montane Birds

Parc National La Visite, Haiti: a last refuge for the country’s montane birds Liliana M. Dávalos and Thomas Brooks Cotinga 16 (2001): 32–35 Le Parc National La Visite, situé au sud est d’Haîti, abrite le seul grand ensemble forestier de montagne du Massif de la Selle, composé de feuillus et de conifères. Cet article présente les archives et les données actuelles concernant la liste des espèces menacées et endémiques, bases sur des références bibliographiques et sur une visite effectuée début janvier 2000. Au moins 24 espèces endémiques et 12 espèces considérées comme menacées/presque-menacées dans la liste Birds to watch 23 sont présentes dans le parc La Visite, qui est de plus une zone privilégié pour le Pétrel diablotin Pterodroma hasitata et pour la Merle de la Selle Turdus swalesi. A cause de la déforestation important du reste de l’île, le parc de La Visite constitue clairement une zone de conservation pour la faune endémique et menacée d’Haîti. Nous espérons avec cet article attirer l’attention des visiteurs et des scientifiques sur ce parc, et ainsi accroître les efforts de conservations déjà entrepris. El Parque Nacional La Visite, al sureste de Haití, contiene el único remanente considerable de bosque montano y de pinos en el Macizo de la Selle. En este artículo resumimos los registros contemporáneos e históricos para el parque de especies globalmente amenazadas o endémicas, con base en la literatura y una breve visita en enero del 2000. Por lo menos 24 especies endémicas y 12 especies señaladas como amenazadas/casi amenazadas en Birds to watch 23 han sido reportadas en La Visite, y el parque es un refugio global para el Diablotín Pterodroma hasitata y el Zorzal de la Selle Turdus swalesi. -

Toward Sustainable Cultivation of Pinus Occidentalis in Haiti: Effects Of

Article Toward Sustainable Cultivation of Pinus occidentalis Swartz in Haiti: Effects of Alternative Growing Media and Containers on Seedling Growth and Foliar Chemistry Kyrstan L. Hubbel 1, Amy L. Ross-Davis 2, Jeremiah R. Pinto 3, Owen T. Burney 4 and Anthony S. Davis 2,* ID 1 Center for Forest Nursery and Seedling Research, University of Idaho, 1025 Plant Science Road, Moscow, ID 83843, USA; [email protected] 2 College of Forestry, Oregon State University, 109 Richardson Hall, Corvallis, OR 97331, USA; [email protected] 3 USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, 1221 South Main Street, Moscow, ID 83843, USA; [email protected] 4 College of Agricultural, Consumer, and Environmental Sciences, New Mexico State University, John T. Harrington Forestry Research Center, 3021 Highway 518, Mora, NM 87732, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 8 June 2018; Accepted: 10 July 2018; Published: 13 July 2018 Abstract: Haiti has suffered great losses from deforestation, with little forest cover remaining today. Current reforestation efforts focus on seedling quantity rather than quality. This study examined limitations to the production of high-quality seedlings of the endemic Hispaniolan pine (Pinus occidentalis Swartz). Recognizing the importance of applying sustainable development principles to pine forest restoration, the effects of growing media and container types on seedling growth were evaluated with the goal of developing a propagation protocol to produce high-quality seedlings using economically feasible nursery practices. With regard to growing media, seedlings grew best in compost-based media amended with sand. Topsoil, widely used in nurseries throughout Haiti, produced the smallest seedlings overall. -

Memoirs of the Museum of Comparative Zoölogy, at Harvard

v^^<^^u^ /IDemotrs of tbe /IDuseum of Comparative 2;oologs AT HARVARD COLLEGE. Vol. XLIV. No. 2. A CONTRIBUTION TO THE ZOOGEOGKAPHY OF THE WEST INDIES, WITH ESPECIAL KEFERENCE TO AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES. BY THOMAS BARBOUR. WITH ONE PLATE. CAMBRIDGE, U.S.A.: printed foe tbe rtDuseum. March, 1914. /iDemotrs of tbe flDuseum of Comparattve Zoology AT HARVARD COLLEGE. Vol. XLIV. No. 2. A CONTRIBUTION TO THE ZOOGEOGRArHY OF THE WEST INDIES, WITH ESPECIAL REFERENCE TO AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES. BY THOMAS BARBOUR. WITH ONE PLATE. CAMBRIDGE, U.S.A.: prlnteJ) for tbe /IDuseum. March, 1914. TABLE OF CONTENTS. Page. INTRODUCTION ' 209 Note 213 LIST OF SPECIES INCORRECTLY RECORDED FROM THE WEST INDIES 217 INTRODUCED SPECIES {Fortuitously or otherwise) 220 ZOOGEOGRAPHY 224 Cuba 224 Jamaica 227 Haiti and San Domingo . 227 Porto Rico 228 The Virgin Islands 229 The Lesser Antilles 230 Grenada 230 CONCLUSIONS 236 ANNOTATED LIST OF THE SPECIES 238 TABLE OF DISTRIBUTION 347 PLATE A CONTRIBUTION TO THE ZOOGEOGRArilY OF THE WEST INDIES, WITH ESPECIAL REFERENCE TO AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES. INTRODUCTION. Since its earliest years the Museum of Comparative Zoology has received many collections representing the fauna of the West Indian Islands. To men- tion a few of these, Louis Agassiz and the other scientists on the Hassler col- lected at St. Thomas, on their memorable voyage; and later — from 1877 to 1880 — the Blake visited very many of the islands. The opportunity to col- lect upon all of them was eagei'ly grasped by Mr. Samuel Garman, who was Assistant Naturalist on the Blake during part of the time that she was in charge of Alexander Agassiz.