Field Observations on the Behavioral Ecology of the Madagascan Leaf-Nosed Snake, Langaha Madagascariensis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uromacer Catesbyi (Schlegel) 1. Uromacer Catesbyi Catesbyi Schlegel 2. Uromacer Catesbyi Cereolineatus Schwartz 3. Uromacer Cate

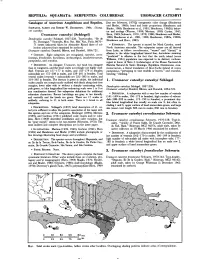

T 356.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SERPENTES: COLUBRIDAE UROMACER CATESBYI Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. [but see Schwartz,' 1970]); ontogenetic color change (Henderson and Binder, 1980); head and body proportions (Henderson and SCHWARTZ,ALBERTANDROBERTW. HENDERSON.1984. Uroma• Binder, 1980; Henderson et a\., 1981; Henderson, 1982b); behav• cer catesbyi. ior and ecology (Werner, 1909; Mertens, 1939; Curtiss, 1947; Uromacer catesbyi (Schlegel) Horn, 1969; Schwartz, 1970, 1979, 1980; Henderson and Binder, 1980; Henderson et a\., 1981, 1982; Henderson, 1982a, 1982b; Dendrophis catesbyi Schlegel, 1837:226. Type-locality, "lie de Henderson and Horn, 1983). St.- Domingue." Syntypes, Mus. Nat. Hist. Nat., Paris, 8670• 71 (sexes unknown) taken by Alexandre Ricord (date of col• • ETYMOLOGY.The species is named for Mark Catesby, noted lection unknown) (not examined by authors). North American naturalist. The subspecies names are all derived Uromacer catesbyi: Dumeril, Bibron, and Dumeril, 1854:72l. from Latin, as follow: cereolineatus, "waxen" and "thread," in allusion to the white longitudinal lateral line; hariolatus meaning • CONTENT.Eight subspecies are recognized, catesbyi, cereo• "predicted" in allusion to the fact that the north island (sensu lineatus,frondicolor, hariolatus, inchausteguii, insulaevaccarum, Williams, 1961) population was expected to be distinct; inchaus• pampineus, and scandax. teguii in honor of Sixto J. Inchaustegui, of the Museo Nacional de • DEFINITION.An elongate Uromacer, but head less elongate Historia Natural de Santo Domingo, Republica Dominicana; insu• than in congeners, and the head scales accordingly not highly mod• laevaccarum, a literal translation of lIe-a-Vache (island of cows), ified. Ventrals are 157-177 in males, and 155-179 in females; pampineus, "pertaining to vine tendrils or leaves;" and scandax, subcaudals are 172-208 in males, and 159-201 in females. -

Blumgart Et Al 2017- Herpetological Survey Nosy Komba

Journal of Natural History ISSN: 0022-2933 (Print) 1464-5262 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tnah20 Herpetological diversity across intact and modified habitats of Nosy Komba Island, Madagascar Dan Blumgart, Julia Dolhem & Christopher J. Raxworthy To cite this article: Dan Blumgart, Julia Dolhem & Christopher J. Raxworthy (2017): Herpetological diversity across intact and modified habitats of Nosy Komba Island, Madagascar, Journal of Natural History, DOI: 10.1080/00222933.2017.1287312 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00222933.2017.1287312 Published online: 28 Feb 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 23 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tnah20 Download by: [BBSRC] Date: 21 March 2017, At: 02:56 JOURNAL OF NATURAL HISTORY, 2017 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00222933.2017.1287312 Herpetological diversity across intact and modified habitats of Nosy Komba Island, Madagascar Dan Blumgart a, Julia Dolhema and Christopher J. Raxworthyb aMadagascar Research and Conservation Institute, BP 270, Hellville, Nosy Be, Madagascar; bDivision of Vertebrate Zoology, American, Museum of Natural History, New York, NY, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY A six month herpetological survey was undertaken between March Received 16 August 2016 and September 2015 on Nosy Komba, an island off of the north- Accepted 17 January 2017 west coast of mainland Madagascar which has undergone con- KEYWORDS fi siderable anthropogenic modi cation. A total of 14 species were Herpetofauna; conservation; found that have not been previously recorded on Nosy Komba, Madagascar; Nosy Komba; bringing the total island diversity to 52 (41 reptiles and 11 frogs). -

Zootaxa, Molecular Phylogeny, Classification, and Biogeography Of

Zootaxa 2067: 1–28 (2009) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2009 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) Molecular phylogeny, classification, and biogeography of West Indian racer snakes of the Tribe Alsophiini (Squamata, Dipsadidae, Xenodontinae) S. BLAIR HEDGES1, ARNAUD COULOUX2, & NICOLAS VIDAL3,4 1Department of Biology, 208 Mueller Lab, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802-5301 USA. E-mail: [email protected] 2Genoscope. Centre National de Séquençage, 2 rue Gaston Crémieux, CP5706, 91057 Evry Cedex, France www.genoscope.fr 3UMR 7138, Département Systématique et Evolution, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, CP 26, 57 rue Cuvier, 75005 Paris, France 4Corresponding author. E-mail : [email protected] Abstract Most West Indian snakes of the family Dipsadidae belong to the Subfamily Xenodontinae and Tribe Alsophiini. As recognized here, alsophiine snakes are exclusively West Indian and comprise 43 species distributed throughout the region. These snakes are slender and typically fast-moving (active foraging), diurnal species often called racers. For the last four decades, their classification into six genera was based on a study utilizing hemipenial and external morphology and which concluded that their biogeographic history involved multiple colonizations from the mainland. Although subsequent studies have mostly disagreed with that phylogeny and taxonomy, no major changes in the classification have been proposed until now. Here we present a DNA sequence analysis of five mitochondrial genes and one nuclear gene in 35 species and subspecies of alsophiines. Our results are more consistent with geography than previous classifications based on morphology, and support a reclassification of the species of alsophiines into seven named and three new genera: Alsophis Fitzinger (Lesser Antilles), Arrhyton Günther (Cuba), Borikenophis Hedges & Vidal gen. -

Ecosystem Profile Madagascar and Indian

ECOSYSTEM PROFILE MADAGASCAR AND INDIAN OCEAN ISLANDS FINAL VERSION DECEMBER 2014 This version of the Ecosystem Profile, based on the draft approved by the Donor Council of CEPF was finalized in December 2014 to include clearer maps and correct minor errors in Chapter 12 and Annexes Page i Prepared by: Conservation International - Madagascar Under the supervision of: Pierre Carret (CEPF) With technical support from: Moore Center for Science and Oceans - Conservation International Missouri Botanical Garden And support from the Regional Advisory Committee Léon Rajaobelina, Conservation International - Madagascar Richard Hughes, WWF – Western Indian Ocean Edmond Roger, Université d‘Antananarivo, Département de Biologie et Ecologie Végétales Christopher Holmes, WCS – Wildlife Conservation Society Steve Goodman, Vahatra Will Turner, Moore Center for Science and Oceans, Conservation International Ali Mohamed Soilihi, Point focal du FEM, Comores Xavier Luc Duval, Point focal du FEM, Maurice Maurice Loustau-Lalanne, Point focal du FEM, Seychelles Edmée Ralalaharisoa, Point focal du FEM, Madagascar Vikash Tatayah, Mauritian Wildlife Foundation Nirmal Jivan Shah, Nature Seychelles Andry Ralamboson Andriamanga, Alliance Voahary Gasy Idaroussi Hamadi, CNDD- Comores Luc Gigord - Conservatoire botanique du Mascarin, Réunion Claude-Anne Gauthier, Muséum National d‘Histoire Naturelle, Paris Jean-Paul Gaudechoux, Commission de l‘Océan Indien Drafted by the Ecosystem Profiling Team: Pierre Carret (CEPF) Harison Rabarison, Nirhy Rabibisoa, Setra Andriamanaitra, -

Cop13 Analyses Cover 29 Jul 04.Qxd

IUCN/TRAFFIC Analyses of the Proposals to Amend the CITES Appendices at the 13th Meeting of the Conference of the Parties Bangkok, Thailand 2-14 October 2004 Prepared by IUCN Species Survival Commission and TRAFFIC Production of the 2004 IUCN/TRAFFIC Analyses of the Proposals to Amend the CITES Appendices was made possible through the support of: The Commission of the European Union Canadian Wildlife Service Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality, Department for Nature, the Netherlands Federal Agency for Nature Conservation, Germany Federal Veterinary Office, Switzerland Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, Dirección General para la Biodiversidad (Spain) Ministère de l'écologie et du développement durable, Direction de la nature et des paysages (France) IUCN-The World Conservation Union IUCN-The World Conservation Union brings together states, government agencies and a diverse range of non-governmental organizations in a unique global partnership - over 1 000 members in some 140 countries. As a Union, IUCN seeks to influence, encourage and assist societies throughout the world to conserve the integrity and diversity of nature and to ensure that any use of natural resources is equitable and ecologically sustainable. IUCN builds on the strengths of its members, networks and partners to enhance their capacity and to support global alliances to safeguard natural resources at local, regional and global levels. The Species Survival Commission (SSC) is the largest of IUCN’s six volunteer commissions. With 8 000 scientists, field researchers, government officials and conservation leaders, the SSC membership is an unmatched source of information about biodiversity conservation. SSC members provide technical and scientific advice to conservation activities throughout the world and to governments, international conventions and conservation organizations. -

PNA Couleuvre De Mayotte 2021-2030 Consultation

Plan national d’actions 2021 - 2030 En faveur de la Couleuvre de Mayotte Liophidium mayottensis Avril 2021 PLAN NATIONAL D’ACTIONS | Couleuvre de Mayotte 2021-2030 Remerciements pour leur contribution : Abassi Dimassi (Conservatoire Botanique de Mascarin) Anna Roger (RNN M’Bouzi) Annabelle Morcrette (ONF) Antoine Baglan (Eco-Med Océan Indien) Axel Marchelie (photographe indépendant) Emilien Dautrey (GEPOMAY) Gaspard Bernard (naturaliste indépendant) Ivan Ineich (MNHN) Julien Paillusseau (ZOSTEROPS Créations) Laurent Barthe (Société Herpétologique de France) Mathieu Booghs (DAAF Mayotte) Michel Charpentier (association des Naturalistes de Mayotte) Norbert Verneau (naturaliste indépendant) Oliver Hawlitschek (Université de Hambourg) Patrick Ingremeau (naturaliste indépendant) Raïma Fadul (Conseil départemental de Mayotte) Rémy Eudeline (naturaliste indépendant) Romain Delarue (GAL Nord et Centre de Mayotte) Stéphanie Thienpont (Société Herpétologique de France) Thomas Ferrari (GEPOMAY) Yohann Legraverant (Conservatoire du littoral) Citation 2021. Augros S. et al. (Coord.) Plan National d’Actions en faveur de la Couleuvre de Mayotte (Liophidium mayottensis) 2021-2030. DEAL Mayotte. 111 p. Couverture : Liophidium mayottensis, photo réalisée par Patrick Ingremeau Ministère de la transition écologique et solidaire 2 PLAN NATIONAL D’ACTIONS | Couleuvre de Mayotte 2021-2030 Table des matières RESUME / ABSTRACT ......................................................................................................................... 6 1. BILAN DES -

Ancestral Reconstruction of Diet and Fang Condition in the Lamprophiidae: Implications for the Evolution of Venom Systems in Snakes

Journal of Herpetology, Vol. 55, No. 1, 1–10, 2021 Copyright 2021 Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles Ancestral Reconstruction of Diet and Fang Condition in the Lamprophiidae: Implications for the Evolution of Venom Systems in Snakes 1,2 1 1 HIRAL NAIK, MIMMIE M. KGADITSE, AND GRAHAM J. ALEXANDER 1School of Animal, Plant and Environmental Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. PO Wits, 2050, Gauteng, South Africa ABSTRACT.—The Colubroidea includes all venomous and some nonvenomous snakes, many of which have extraordinary dental morphology and functional capabilities. It has been proposed that the ancestral condition of the Colubroidea is venomous with tubular fangs. The venom system includes the production of venomous secretions by labial glands in the mouth and usually includes fangs for effective delivery of venom. Despite significant research on the evolution of the venom system in snakes, limited research exists on the driving forces for different fang and dental morphology at a broader phylogenetic scale. We assessed the patterns of fang and dental condition in the Lamprophiidae, a speciose family of advanced snakes within the Colubroidea, and we related fang and dental condition to diet. The Lamprophiidae is the only snake family that includes front-fanged, rear-fanged, and fangless species. We produced an ancestral reconstruction for the family and investigated the pattern of diet and fangs within the clade. We concluded that the ancestral lamprophiid was most likely rear-fanged and that the shift in dental morphology was associated with changes in diet. This pattern indicates that fang loss, and probably venom loss, has occurred multiple times within the Lamprophiidae. -

Review of the Malagasy Tree Snakes of the Genus Stenophis (Colubridae)

Review of the Malagasy tree snakes of the genus Stenophis (Colubridae) Review of the Malagasy tree snakes of the genus Stenophis (Colubridae) MIGUEL VENCES, FRANK GLAW, VINCENZO MERCURIO & FRANCO ANDREONE Abstract We provide a review of the tree snakes in the Malagasy genus Stenophis, based on examination of types, additional voucher specimens, and field observations. We document live colouration for eight species. The validity of several recently described taxa is considered as questionable here, and three of these are treated as junior synonyms: Stenophis capuroni as synonym of S. granuliceps, S. jaosoloa of S. arctifasciatus, and S. tulearensis of S. variabilis. Also the status of S. carleti is uncertain; this taxon is similar to S. gaimardi. In contrast, some additional species may be recognized in the future. The available material of S. betsileanus contains large and small specimens with a distinct size gap (275-315 vs. 920-985 mm snout-vent length). A specimen from Benavony in north-western Madagascar is characterized by a unique combination of meristic and chromatic characters, probably indicating taxonomic distinctness. Stenophis inopinae shares more characters with species classified in the subgenus Stenophis (17 dorsal scale rows, relatively short tail, low number of subcaudal scales, iris colouration) than with the subgenus Phisalixella, indicating that its current classification should be evaluated. Some species seem to be closely related species pairs with allopatric distributions: Stenophis gaimardi (east) and S. carleti (south-east), S. granuliceps (north-west) and S. pseudogranuliceps (west), S. arctifasciatus (east) and S. variabilis (west). Key words: Squamata: Serpentes: Colubridae: Stenophis; taxonomy; distribution; Madagascar. 1 Introduction The colubrid snakes of Madagascar comprise 18 genera (GLAW & VENCES 1994, CADLE 1999). -

Genetic Diversity Among Eight Egyptian Snakes (Squamata-Serpents: Colubridae) Using RAPD-PCR

Life Science Journal, 2012;9(1) http://www.lifesciencesite.com Genetic Diversity among Eight Egyptian Snakes (Squamata-Serpents: Colubridae) Using RAPD-PCR Nadia H. M. Sayed Zoology Dept., College for Women for Science, Arts and Education, Ain Shams University, Heliopolis, Cairo, Egypt. [email protected] Abstract: Genetic variations between 8 Egyptian snake species, Psammophis sibilans sibilans, Psammophis Sudanensis, Psammophis Schokari Schokari, Psammophis Schokari aegyptiacus, Spalerosophis diadema, Lytorhynchus diadema, , Coluber rhodorhachis, Coluber nummifer were conducted using RAPD-PCR. Animals were captured from several locality of Egypt (Abu Rawash-Giza, Sinai and Faiyum). Obtained results revealed a total of 59 bands which were amplified by the five primers OPB-01, OPB-13, OPB-14, OPB-20 and OPE-05 with an average 11.8 bands per primer at molecular weights ranged from 3000-250 bp. The polymorphic loci between both species were 54 with percentage 91.5 %. The mean band frequency was 47% ranging from 39% to 62% per primer .The similarity matrix value between the 8 Snakes species was ranged from 0.35 (35%) to 0.71 (71%) with an average of 60%. The genetic distance between the 8 colubrid species was ranged from 0.29 (29%) to 0.65 (65%) with an average of 40 %. Dendrogram showed that, the 8 snake species are separated from each other into two clusters .The first cluster contain 4 species of the genus Psammophis. The second cluster includes the 4 species of the genera, Spalerosophis; Coluber and Lytorhynchus. Psammophis sibilans is sister to Psammophis Sudanensis with high genetic similarity (71%) and Psammophis Schokari Schokari is sister to Psammophis Schokari aegyptiacus with high genetic similarity (70%). -

Reptiles & Amphibians of Kirindy

REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS OF KIRINDY KIRINDY FOREST is a dry deciduous forest covering about 12,000 ha and is managed by the Centre National de Formation, dʹEtudes et de Recherche en Environnement et Foresterie (CNFEREF). Dry deciduous forests are among the world’s most threatened ecosystems, and in Madagascar they have been reduced to 3 per cent of their original extent. Located in Central Menabe, Kirindy forms part of a conservation priority area and contains several locally endemic animal and plant species. Kirindy supports seven species of lemur and Madagascarʹs largest predator, the fossa. Kirindy’s plants are equally notable and include two species of baobab, as well as the Malagasy endemic hazomalany tree (Hazomalania voyroni). Ninety‐nine per cent of Madagascar’s known amphibians and 95% of Madagascar’s reptiles are endemic. Kirindy Forest has around 50 species of reptiles, including 7 species of chameleons and 11 species of snakes. This guide describes the common amphibians and reptiles that you are likely to see during your stay in Kirindy forest and gives some field notes to help towards their identification. The guide is specifically for use on TBA’s educational courses and not for commercial purposes. This guide would not have been possible without the photos and expertise of Marius Burger. Please note this guide is a work in progress. Further contributions of new photos, ids and descriptions to this guide are appreciated. This document was developed during Tropical Biology Association field courses in Kirindy. It was written by Rosie Trevelyan and designed by Brigid Barry, Bonnie Metherell and Monica Frisch. -

Natural History and Taxonomic Notes On

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 9(2):406–416. Submitted: 27 March 2014; Accepted: 25 May 2014; Published: 12 October 2014. NATURAL HISTORY AND TAXONOMIC NOTES ON LIOPHOLIDOPHIS GRANDIDIERI MOCQUARD, AN UPLAND RAIN FOREST SNAKE FROM MADAGASCAR (SERPENTES: LAMPROPHIIDAE: PSEUDOXYRHOPHIINAE) JOHN E. CADLE1, 2 1Centre ValBio, B.P. 33, 312 Ranomafana-Ifanadiana, Madagascar 2Department of Herpetology, California Academy of Sciences, Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, California 94118, USA, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract.––Few observations on living specimens of the Malagasy snake Liopholidophis grandidieri Mocquard have been previously reported. New field observations and specimens from Ranomafana National Park amplify knowledge of the natural history of this species. Liopholidophis grandidieri is known from above 1200 m elevation in pristine rain forests with a high diversity of hardwoods and bamboo. In some areas of occurrence, the forests are of short stature (15–18 m) as a result of lying atop well-drained boulder fields with a thin soil layer. Dietary data show that this species consumes relatively small mantellid and microhylid frogs obtained on the ground or in phytotelms close to the ground. A female collected in late December contained four oviductal eggs with leathery shells. One specimen formed a rigid, loose set of coils and body loops, and hid the head as presumed defensive behaviors; otherwise, all individuals were complacent when handled and showed no tendency to bite. I describe coloration and present photographs of living specimens from Ranomafana National Park. The ventral colors of L. grandidieri were recently said to be aposematic, but I discuss other plausible alternatives. Key Words.––conservation; diet; habitat; reproduction; snakes; systematics exhibits the greatest sexual dimorphism in tail length and INTRODUCTION the greatest reported relative tail length of any snake (tails average 18% longer than body length in males; The natural history and systematics of many snake Cadle 2009). -

Revisión Periódica De Reservas De La Biosfera

2 REVISIÓN PERIÓDICA DE RESERVAS DE LA BIOSFERA [Enero de 2013] INTRODUCCIÓN La Conferencia General de la UNESCO, en su 28ª sesión, adoptó la Resolución 28 C/2.4 en el Marco Estatutario de la Red Mundial de Reservas de la Biosfera. Este texto define en particular, los criterios para que un área esté cualificada para ser designada como reserva de la biosfera (Artículo 4). Además, el Artículo 9 contempla una revisión periódica cada 10 años, que consiste en un informe que debe preparar la autoridad competente, en base a los criterios del Artículo 4 y enviarlo al secretariado del Estado correspondiente. El texto del Marco Estatutario se recoge en el tercer anexo. El formulario que se facilita a continuación sirve para ayudar a los Estados a preparar su informe nacional, de acuerdo con el Artículo 9, y para actualizar en la Secretaria los datos disponibles de la reserva de la biosfera correspondiente. Este informe deber permitir al Consejo Internacional de Coordinación (CIC) del Programa MAB, revisar cómo cada reserva de la biosfera está cumpliendo con los criterios del Artículo 4 del Marco Estatutario y en particular con las tres funciones. Cabe señalar que en la última parte del formulario (Criterios y Avances Logrados), se pide que se indique cómo las reservas de la biosfera cumplen con cada uno de estos criterios. La UNESCO utilizará de diversas maneras la información presentada en esta revisión periódica: (a) para la evaluación de la reserva de la biosfera por parte del Comité Consultivo Internacional de las Reservas de Biosfera y por la Mesa del Consejo Internacional de Coordinación del MAB; (b) para utilizarla en un sistema de información accesible a nivel mundial, en particular la red UNESCO-MAB y publicaciones, facilitando así la comunicación y la interacción entre personas interesadas en las reservas de la biosfera en todo el mundo.