Cop13 Analyses Cover 29 Jul 04.Qxd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparative Study of NZ Pine & Selected SE Asian Species

(FRONT COVER) A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF NEW ZEALAND PINE AND SELECTED SOUTH EAST ASIAN SPECIES (INSIDE FRONT COVER) NEW ZEALAND PINE - A RENEWABLE RESOURCE NZ pine (Pinus radiata D. Don) was introduced to New Zealand (NZ) from the USA about 150 years ago and has gained a dominant position in the New Zealand forest industry - gradually replacing timber from natural forests and establishing a reputation in international trade. The current log production from New Zealand forests (1998) is 17 million m3, of which a very significant proportion (40%) is exported as wood products of some kind. Estimates of future production indicate that by the year 2015 the total forest harvest could be about 35 million m3. NZ pine is therefore likely to be a major source of wood for Asian wood manufacturers. This brochure has been produced to give prospective wood users an appreciation of the most important woodworking characteristics for high value uses. Sponsored by: Wood New Zealand Ltd. Funded by: New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade Written by: New Zealand Forest Research Institute Ltd. (Front page - First sheet)) NEW ZEALAND PINE - A VERSATILE TIMBER NZ pine (Pinus radiata D.Don) from New Zealand is one of the world’s most versatile softwoods - an ideal material for a wide range of commercial applications. Not only is the supply from sustainable plantations increasing, but the status of the lumber as a high quality resource has been endorsed by a recent comparison with six selected timber species from South East Asia. These species were chosen because they have similar end uses to NZ pine. -

Blumgart Et Al 2017- Herpetological Survey Nosy Komba

Journal of Natural History ISSN: 0022-2933 (Print) 1464-5262 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tnah20 Herpetological diversity across intact and modified habitats of Nosy Komba Island, Madagascar Dan Blumgart, Julia Dolhem & Christopher J. Raxworthy To cite this article: Dan Blumgart, Julia Dolhem & Christopher J. Raxworthy (2017): Herpetological diversity across intact and modified habitats of Nosy Komba Island, Madagascar, Journal of Natural History, DOI: 10.1080/00222933.2017.1287312 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00222933.2017.1287312 Published online: 28 Feb 2017. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 23 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tnah20 Download by: [BBSRC] Date: 21 March 2017, At: 02:56 JOURNAL OF NATURAL HISTORY, 2017 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00222933.2017.1287312 Herpetological diversity across intact and modified habitats of Nosy Komba Island, Madagascar Dan Blumgart a, Julia Dolhema and Christopher J. Raxworthyb aMadagascar Research and Conservation Institute, BP 270, Hellville, Nosy Be, Madagascar; bDivision of Vertebrate Zoology, American, Museum of Natural History, New York, NY, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY A six month herpetological survey was undertaken between March Received 16 August 2016 and September 2015 on Nosy Komba, an island off of the north- Accepted 17 January 2017 west coast of mainland Madagascar which has undergone con- KEYWORDS fi siderable anthropogenic modi cation. A total of 14 species were Herpetofauna; conservation; found that have not been previously recorded on Nosy Komba, Madagascar; Nosy Komba; bringing the total island diversity to 52 (41 reptiles and 11 frogs). -

Biosynthesis of Indigo Using Recombinant E. Coli: Development of a Biological System for the Cost Effective Production of a Large Volume Chemical

BIOSYNTHESIS OF INDIGO USING RECOMBINANT E. COLI: DEVELOPMENT OF A BIOLOGICAL SYSTEM FOR THE COST EFFECTIVE PRODUCTION OF A LARGE VOLUME CHEMICAL Alan Berry, Ph.D., Senior Scientist; Scott Battist, B.S., Ch.E., Development Engineer; Gopal Chotani, Ph.D., Ch.E., Senior Staff Scientist; Tim Dodge, M.S., Ch.E., Senior Scientist; Steve Peck, B.S., Ch.E., Development Engineer; Scott Power, Ph.D., Vice President and Research Fellow; and Walter Weyler, Ph.D., Senior Scientist Genencor International. Rochester, NY. 14618-3916. Abstract Cost-effective production of any large-volume chemical by fermentation requires extensive manipulation ofboth the production organism and the fermentation and recovery processes. We have developed a recombinant E. coli system for the production of tryptophan and several other products derived from the aromatic amino acid pathway. By linking our technology for low-cost production oftryptophan from glucose with the enzyme naphthalene dioxygenase (NOO), we have achieved an overall process for the production ofindigo dye from glucose. To successfully join these two technologies, both the tryptophan pathway and NOD were extensively modified via genetic engineering. In addition, systems were developed to remove deleterious by-products generated during the chemical oxidations leading to indigo formation. Low-cost fermentation processes were developed that utilized minimal-salts media containing glucose as the sole carbon source. Finally, economical recovery processes were used that preserved the environmental friendliness ofthe biosynthetic route to indigo. 1121 Introduction Two major problems facing the U.S. chemical industry are dependence on foreign petroleum and mounting environmental concerns and regulations (for review, see reference [1]). This has led to consideration ofbiosynthetic routes for production of aromatic compounds. -

Ecosystem Profile Madagascar and Indian

ECOSYSTEM PROFILE MADAGASCAR AND INDIAN OCEAN ISLANDS FINAL VERSION DECEMBER 2014 This version of the Ecosystem Profile, based on the draft approved by the Donor Council of CEPF was finalized in December 2014 to include clearer maps and correct minor errors in Chapter 12 and Annexes Page i Prepared by: Conservation International - Madagascar Under the supervision of: Pierre Carret (CEPF) With technical support from: Moore Center for Science and Oceans - Conservation International Missouri Botanical Garden And support from the Regional Advisory Committee Léon Rajaobelina, Conservation International - Madagascar Richard Hughes, WWF – Western Indian Ocean Edmond Roger, Université d‘Antananarivo, Département de Biologie et Ecologie Végétales Christopher Holmes, WCS – Wildlife Conservation Society Steve Goodman, Vahatra Will Turner, Moore Center for Science and Oceans, Conservation International Ali Mohamed Soilihi, Point focal du FEM, Comores Xavier Luc Duval, Point focal du FEM, Maurice Maurice Loustau-Lalanne, Point focal du FEM, Seychelles Edmée Ralalaharisoa, Point focal du FEM, Madagascar Vikash Tatayah, Mauritian Wildlife Foundation Nirmal Jivan Shah, Nature Seychelles Andry Ralamboson Andriamanga, Alliance Voahary Gasy Idaroussi Hamadi, CNDD- Comores Luc Gigord - Conservatoire botanique du Mascarin, Réunion Claude-Anne Gauthier, Muséum National d‘Histoire Naturelle, Paris Jean-Paul Gaudechoux, Commission de l‘Océan Indien Drafted by the Ecosystem Profiling Team: Pierre Carret (CEPF) Harison Rabarison, Nirhy Rabibisoa, Setra Andriamanaitra, -

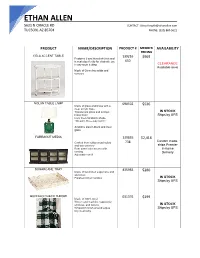

Ethan Allen 5621 N Oracle Rd

ETHAN ALLEN 5621 N ORACLE RD. CONTACT: [email protected] TUCSON, AZ 85704 PHONE: (520) 887-5621 PRODUCT NAME/DESCRIPTION PRODUCT # MEMBER AVAILABILITY PRICING CELA ACCENT TABLE 139216 $969 Features 3 oval tiered shelves and is scaled perfectly for chairside use 650 CLEARANCE in any room setting Available as-is Made of Gemelina solids and veneers NOLAN TABLE LAMP 090502 Made of glass and brass with a $536 clear acrylic base Translucent glass and antique IN STOCK brass finish Ships by UPS Ivory linen hardback shade 100-watt, three-way switch Available also in black and clear glass FARRAGUT MEDIA 139855 $2,416 Custom made, Crafted from rubberwood solids 738 ships Premier and oak veneers* Rear panel wire access with In-home venting Delivery Adjustable shelf SUGARCANE TRAY 435983 Made of laminated sugarcane and $280 aluminum Polished nickel handles IN STOCK Ships by UPS BUFFALO CHECK THROW 031376 Made of 100% wool $199 Woven and machine napped for softness, and texture IN STOCK Whipstitch finish around edges Ships by UPS Dry clean only ETHAN ALLEN 5621 N ORACLE RD. CONTACT: [email protected] TUCSON, AZ 85704 PHONE: (520) 887-5621 GREEN LIDDED JAR 430511 $184 Made of porcelain IN STOCK Hand-painted finish Removable lid Ships by UPS Not for food use BAILEY ISLAND BASKET 430507 $232 Made of seagrass and leather IN STOCK Natural finish Some variations are to be expected Ships by UPS DARK ABACA STORAGE BASKET 439833 $96 Made of madras rope IN STOCK Natural finish Ships by UPS MARA BLACK BOWL Large $89 Made of ceramic 430562A IN STOCK Black glaze Not food safe Ships by UPS Small 430562B $69 WHITE SNOWBALL GARDEN 446634A $928 • White snowball hydrangeas with IN STOCK leaves Ships by UPS • Clear glass cylinder • Container dimensions: 8" dia. -

Quantifying the Conservation Value of Plantation Forests for a Madagascan Herpetofauna

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 14(1):269–287. Submitted: 6 March 2018; Accepted: 28 March 2019; Published: 30 April 2019. QUANTIFYING THE CONSERVATION VALUE OF PLANTATION FORESTS FOR A MADAGASCAN HERPETOFAUNA BETH EVANS Madagascar Research and Conservation Institute, Nosy Komba, Madagascar current address: 121 Heathway, Erith, Kent DA8 3LZ, UK, email: [email protected] Abstract.—Plantations are becoming a dominant component of the forest landscape of Madagascar, yet there is very little information available regarding the implications of different forms of plantation agriculture for Madagascan reptiles and amphibians. I determined the conservation value of bamboo, secondary, open-canopy plantation, and closed-canopy plantation forests for reptiles and amphibians on the island of Nosy Komba, in the Sambirano region of north-west Madagascar. Assistants and I conducted 220 Visual Encounter Surveys between 29 January 2016 and 5 July 2017 and recorded 3,113 reptiles (32 species) and 751 amphibians (nine species). Closed-canopy plantation supported levels of alpha diversity and community compositions reflective of natural forest, including several threatened and forest-specialist species. Open-canopy plantation exhibited diminished herpetofaunal diversity and a distinct community composition dominated by disturbance-resistant generalist species. Woody tree density and bamboo density were positively correlated with herpetofaunal species richness, and plantation species richness, plantation species density, sapling density, and the proportion of wood ground cover were negatively associated with herpetofaunal diversity. I recommend the integration of closed-canopy plantations on Nosy Komba, and across wider Madagascar, to help mitigate the negative effects of secondary forest conversion for agriculture on Madagascan herpetofauna; however, it will be necessary to retain areas of natural forest to act as sources of biodiversity for agroforestry plantations. -

NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Pharmacol Ther

NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Pharmacol Ther. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2010 August 1. NIH-PA Author ManuscriptPublished NIH-PA Author Manuscript in final edited NIH-PA Author Manuscript form as: Pharmacol Ther. 2009 August ; 123(2): 239±254. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.04.002. Ethnobotany as a Pharmacological Research Tool and Recent Developments in CNS-active Natural Products from Ethnobotanical Sources Will C. McClatcheya,*, Gail B. Mahadyb, Bradley C. Bennettc, Laura Shielsa, and Valentina Savod a Department of Botany, University of Hawaìi at Manoa, Honolulu, HI 96822, U.S.A b Department of Pharmacy Practice, University of Illinois at Chicago, Chicago, IL 60612, U.S.A c Department of Biological Sciences, Florida International University, Miami, FL 33199, U.S.A d Dipartimento di Biologia dì Roma Trè, Viale Marconi, 446, 00146, Rome, Italy Abstract The science of ethnobotany is reviewed in light of its multidisciplinary contributions to natural product research for the development of pharmaceuticals and pharmacological tools. Some of the issues reviewed involve ethical and cultural perspectives of healthcare and medicinal plants. While these are not usually part of the discussion of pharmacology, cultural concerns potentially provide both challenges and insight for field and laboratory researchers. Plant evolutionary issues are also considered as they relate to development of plant chemistry and accessing this through ethnobotanical methods. The discussion includes presentation of a range of CNS-active medicinal plants that have been recently examined in the field, laboratory and/or clinic. Each of these plants is used to illustrate one or more aspects about the valuable roles of ethnobotany in pharmacological research. -

Hoodia Gordonii (Masson) Sweet Ex Decne., 1844

Hoodia gordonii (Masson) Sweet ex Decne., 1844 Identifiants : 16192/hoogor Association du Potager de mes/nos Rêves (https://lepotager-demesreves.fr) Fiche réalisée par Patrick Le Ménahèze Dernière modification le 02/10/2021 Classification phylogénétique : Clade : Angiospermes ; Clade : Dicotylédones vraies ; Clade : Astéridées ; Clade : Lamiidées ; Ordre : Gentianales ; Famille : Apocynaceae ; Classification/taxinomie traditionnelle : Règne : Plantae ; Sous-règne : Tracheobionta ; Division : Magnoliophyta ; Classe : Magnoliopsida ; Ordre : Gentianales ; Famille : Apocynaceae ; Genre : Hoodia ; Synonymes : Hoodia husabensis Nel, Hoodia langii Oberm. & Letty, Hoodia longispina Plowes, Hoodia pillansii N. E. Br, Hoodia rosea Oberm. & Letty, Hoodia whitsloaneana Dinter ex A. C. White & B. Sloane, Hoodia barklyi Dyer, Hoodia burkei N. E. Br, Hoodia bainii Dyer, Hoodia albispina N. E. Br ; Nom(s) anglais, local(aux) et/ou international(aux) : queen of the Namib, African hats , Bitterghaap, Ghoba, Wilde ghaap ; Rapport de consommation et comestibilité/consommabilité inférée (partie(s) utilisable(s) et usage(s) alimentaire(s) correspondant(s)) : Feuille (tiges0(+x) [nourriture/aliment{{{0(+x) et/ou{{{(dp*) masticatoire~~0(+x)]) comestible0(+x). Détails : Les tiges sont mâchées pour{{{0(+x) rassasier et entrainer la satiété{{{(dp*), par exemple dans le cas de régimes{{{(dp*) ; elles sont consommées fraîches comme un aliment ; elles ont un goût amer{{{0(+x). Les tiges sont mâchées pour réduire le désir de nourriture. Ils sont consommés frais comme aliment. Ils ont un goût amer néant, inconnus ou indéterminés.néant, inconnus ou indéterminés. Illustration(s) (photographie(s) et/ou dessin(s)): Curtis´s Botanical Magazine (vol. 102 [ser. 3, vol. 32]: t. 6228, 1876) [W.H. Fitch], via plantillustrations.org Page 1/2 Autres infos : dont infos de "FOOD PLANTS INTERNATIONAL" : Distribution : Une plante tropicale. -

Journal of the East Africa Natural History Society and National Museum

JOURNAL OF THE EAST AFRICA NATURAL HISTORY SOCIETY AND NATIONAL MUSEUM 15 October, 1978 Vol. 31 No. 167 A CHECKLIST OF mE SNAKES OF KENYA Stephen Spawls 35 WQodland Rise, Muswell Hill, London NIO, England ABSTRACT Loveridge (1957) lists 161 species and subspecies of snake from East Mrica. Eighty-nine of these belonging to some 41 genera were recorded from Kenya. The new list contains some 106 forms of 46 genera. - Three full species have been deleted from Loveridge's original checklist. Typhlops b. blanfordii has been synonymised with Typhlops I. lineolatus, Typhlops kaimosae has been synonymised with Typhlops angolensis (Roux-Esteve 1974) and Co/uber citeroii has been synonymised with Meizodon semiornatus (Lanza 1963). Of the 20 forms added to the list, 12 are forms collected for the first time in Kenya but occurring outside its political boundaries and one, Atheris desaixi is a new species, the holotype and paratypes being collected within Kenya. There has also been a large number of changes amongst the 89 original species as a result of revisionary systematic studies. This accounts for the other additions to the list. INTRODUCTION The most recent checklist dealing with the snakes of Kenya is Loveridge (1957). Since that date there has been a significant number of developments in the Kenyan herpetological field. This paper intends to update the nomenclature in the part of the checklist that concerns the snakes of Kenya and to extend the list to include all the species now known to occur within the political boundaries of Kenya. It also provides the range of each species within Kenya with specific locality records . -

Apocynaceae of Namibia

S T R E L I T Z I A 34 The Apocynaceae of Namibia P.V. Bruyns Bolus Herbarium Department of Biological Sciences University of Cape Town Rondebosch 7701 Pretoria 2014 S T R E L I T Z I A This series has replaced Memoirs of the Botanical Survey of South Africa and Annals of the Kirstenbosch Botanic Gardens, which the South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI) inherited from its predecessor organisa- tions. The plant genus Strelitzia occurs naturally in the eastern parts of southern Africa. It comprises three arbores- cent species, known as wild bananas, and two acaulescent species, known as crane flowers or bird-of-paradise flowers. The logo of SANBI is partly based on the striking inflorescence of Strelitzia reginae, a native of the Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal that has become a garden favourite worldwide. It symbolises the commitment of SANBI to champion the exploration, conservation, sustainable use, appreciation and enjoyment of South Africa’s excep- tionally rich biodiversity for all people. EDITOR: Alicia Grobler PROOFREADER: Yolande Steenkamp COVER DESIGN & LAYOUT: Elizma Fouché FRONT COVER PHOTOGRAPH: Peter Bruyns BACK COVER PHOTOGRAPHS: Colleen Mannheimer (top) Peter Bruyns (bottom) Citing this publication BRUYNS, P.V. 2014. The Apocynaceae of Namibia. Strelitzia 34. South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria. ISBN: 978-1-919976-98-3 Obtainable from: SANBI Bookshop, Private Bag X101, Pretoria, 0001 South Africa Tel.: +27 12 843 5000 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.sanbi.org Printed by: Seriti Printing, Tel.: +27 12 333 9757, Website: www.seritiprinting.co.za Address: Unit 6, 49 Eland Street, Koedoespoort, Pretoria, 0001 South Africa Copyright © 2014 by South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI) All rights reserved. -

PNA Couleuvre De Mayotte 2021-2030 Consultation

Plan national d’actions 2021 - 2030 En faveur de la Couleuvre de Mayotte Liophidium mayottensis Avril 2021 PLAN NATIONAL D’ACTIONS | Couleuvre de Mayotte 2021-2030 Remerciements pour leur contribution : Abassi Dimassi (Conservatoire Botanique de Mascarin) Anna Roger (RNN M’Bouzi) Annabelle Morcrette (ONF) Antoine Baglan (Eco-Med Océan Indien) Axel Marchelie (photographe indépendant) Emilien Dautrey (GEPOMAY) Gaspard Bernard (naturaliste indépendant) Ivan Ineich (MNHN) Julien Paillusseau (ZOSTEROPS Créations) Laurent Barthe (Société Herpétologique de France) Mathieu Booghs (DAAF Mayotte) Michel Charpentier (association des Naturalistes de Mayotte) Norbert Verneau (naturaliste indépendant) Oliver Hawlitschek (Université de Hambourg) Patrick Ingremeau (naturaliste indépendant) Raïma Fadul (Conseil départemental de Mayotte) Rémy Eudeline (naturaliste indépendant) Romain Delarue (GAL Nord et Centre de Mayotte) Stéphanie Thienpont (Société Herpétologique de France) Thomas Ferrari (GEPOMAY) Yohann Legraverant (Conservatoire du littoral) Citation 2021. Augros S. et al. (Coord.) Plan National d’Actions en faveur de la Couleuvre de Mayotte (Liophidium mayottensis) 2021-2030. DEAL Mayotte. 111 p. Couverture : Liophidium mayottensis, photo réalisée par Patrick Ingremeau Ministère de la transition écologique et solidaire 2 PLAN NATIONAL D’ACTIONS | Couleuvre de Mayotte 2021-2030 Table des matières RESUME / ABSTRACT ......................................................................................................................... 6 1. BILAN DES -

1995-2006 Activities Report

WILDLIFE WITHOUT BORDERS WILDLIFE WITHOUT BORDERS WITHOUT WILDLIFE M E X I C O The most wonderful mystery of life may well be EDITORIAL DIRECTION Office of International Affairs U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service the means by which it created so much diversity www.fws.gov PRODUCTION from so little physical matter. The biosphere, all Agrupación Sierra Madre, S.C. www.sierramadre.com.mx EDITORIAL REVISION organisms combined, makes up only about one Carole Bullard PHOTOGRAPHS All by Patricio Robles Gil part in ten billion [email protected] Excepting: Fabricio Feduchi, p. 13 of the earth’s mass. [email protected] Patricia Rojo, pp. 22-23 [email protected] Fulvio Eccardi, p. 39 It is sparsely distributed through MEXICO [email protected] Jaime Rojo, pp. 44-45 [email protected] a kilometre-thick layer of soil, Antonio Ramírez, Cover (Bat) On p. 1, Tamul waterfall. San Luis Potosí On p. 2, Lacandon rainforest water, and air stretched over On p. 128, Fisherman. Centla wetlands, Tabasco All rights reserved © 2007, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service a half billion square kilometres of surface. The rights of the photographs belongs to each photographer PRINTED IN Impresora Transcontinental de México EDWARD O. WILSON 1992 Photo: NASA U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE DIVISION OF INTERNATIONAL CONSERVATION WILDLIFE WITHOUT BORDERS MEXICO ACTIVITIES REPORT 1995-2006 U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE At their roots, all things hold hands. & When a tree falls down in the forest, SECRETARÍA DE MEDIO AMBIENTE Y RECURSOS NATURALES MEXICO a star falls down from the sky. CHAN K’IN LACANDON ELDER LACANDON RAINFOREST CHIAPAS, MEXICO FOREWORD onservation of biological diversity has truly arrived significant contributions in time, dedication, and C as a global priority.