First Reported Case of Thrombocytopenia from a Heterodon Nasicus Envenomation T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Snake Bite Protocol

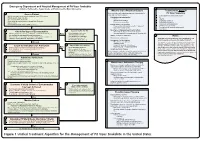

Lavonas et al. BMC Emergency Medicine 2011, 11:2 Page 4 of 15 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-227X/11/2 and other Rocky Mountain Poison and Drug Center treatment of patients bitten by coral snakes (family Ela- staff. The antivenom manufacturer provided funding pidae), nor by snakes that are not indigenous to the US. support. Sponsor representatives were not present dur- At the time this algorithm was developed, the only ing the webinar or panel discussions. Sponsor represen- antivenom commercially available for the treatment of tatives reviewed the final manuscript before publication pit viper envenomation in the US is Crotalidae Polyva- ® for the sole purpose of identifying proprietary informa- lent Immune Fab (ovine) (CroFab , Protherics, Nash- tion. No modifications of the manuscript were requested ville, TN). All treatment recommendations and dosing by the manufacturer. apply to this antivenom. This algorithm does not con- sider treatment with whole IgG antivenom (Antivenin Results (Crotalidae) Polyvalent, equine origin (Wyeth-Ayerst, Final unified treatment algorithm Marietta, Pennsylvania, USA)), because production of The unified treatment algorithm is shown in Figure 1. that antivenom has been discontinued and all extant The final version was endorsed unanimously. Specific lots have expired. This antivenom also does not consider considerations endorsed by the panelists are as follows: treatment with other antivenom products under devel- opment. Because the panel members are all hospital- Role of the unified treatment algorithm -

Western Hognose Snake Care Sheet (Heterodon Nasicus)

Western Hognose Snake Care Sheet (Heterodon nasicus) The western hognose snake is a small, stout bodied colubrid indigenous to north-central Mexico, central North America, and into south-central Canada. Hognose snakes are so named due to their pointed, upturned rostral (nose) scale that enable them to dig through sandy or other loose substrate in search of prey. Hognose snakes are well known for their defensive behaviors. When first encountered, they will produce a loud raspy hiss, flatten their heads and necks to mimic a cobra, and will mock strike in order to appear larger and more intimidating. If that display fails, hognose snakes will often flip themselves upside down and writhe about in the substrate with their mouth open in order to appear dead and lifeless to the predator while excluding a foul smelling musk. Western hognose snakes have become increasingly popular in the reptile industry due to their small size, and rodent eating habits when compared to other species of hognose. *Overall Difficulty Level: Novice Western hognose are a species that are suitable for the beginning reptile owner due to their small size and ease of care provided that one has a general knowledge of reptile, and specifically, snake husbandry. Unlike other North American hognose, captive born and well established western species adapt far more readily to eating rodents making them the most commonly and easily kept species of hognose. Given the proper care, western hognose snakes can attain longevity of 15-25 years on average in captivity. Western Hognose Taxonomy Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Reptilia Order: Squamata Suborder: Serpentes Family: Colubridae Subfamily: Xenodontinae Genus: Heterodon Species Epithet: Heterodon nasicus Size and Description Hatchling western hognose snakes typically range from five to nine inches in length. -

Approach and Management of Spider Bites for the Primary Care Physician

Osteopathic Family Physician (2011) 3, 149-153 Approach and management of spider bites for the primary care physician John Ashurst, DO,a Joe Sexton, MD,a Matt Cook, DOb From the Departments of aEmergency Medicine and bToxicology, Lehigh Valley Health Network, Allentown, PA. KEYWORDS: Summary The class Arachnida of the phylum Arthropoda comprises an estimated 100,000 species Spider bite; worldwide. However, only a handful of these species can cause clinical effects in humans because many Black widow; are unable to penetrate the skin, whereas others only inject prey-specific venom. The bite from a widow Brown recluse spider will produce local symptoms that include muscle spasm and systemic symptoms that resemble acute abdomen. The bite from a brown recluse locally will resemble a target lesion but will develop into an ulcerative, necrotic lesion over time. Spider bites can be prevented by several simple measures including home cleanliness and wearing the proper attire while working outdoors. Although most spider bites cause only local tissue swelling, early species identification coupled with species-specific man- agement may decrease the rate of morbidity associated with bites. © 2011 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. More than 100,000 species of spiders are found world- homes and yards in the southwestern United States, and wide. Persons seeking medical attention as a result of spider related species occur in the temperate climate zones across bites is estimated at 50,000 patients per year.1,2 Although the globe.2,5 The second, Lactrodectus, or the common almost all species of spiders possess some level of venom, widow spider, are found in both temperate and tropical 2 the majority are considered harmless to humans. -

Long-Term Effects of Snake Envenoming

toxins Review Long-Term Effects of Snake Envenoming Subodha Waiddyanatha 1,2, Anjana Silva 1,2 , Sisira Siribaddana 1 and Geoffrey K. Isbister 2,3,* 1 Faculty of Medicine and Allied Sciences, Rajarata University of Sri Lanka, Saliyapura 50008, Sri Lanka; [email protected] (S.W.); [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (S.S.) 2 South Asian Clinical Toxicology Research Collaboration, Faculty of Medicine, University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya 20400, Sri Lanka 3 Clinical Toxicology Research Group, University of Newcastle, Callaghan, NSW 2308, Australia * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +612-4921-1211 Received: 14 March 2019; Accepted: 29 March 2019; Published: 31 March 2019 Abstract: Long-term effects of envenoming compromise the quality of life of the survivors of snakebite. We searched MEDLINE (from 1946) and EMBASE (from 1947) until October 2018 for clinical literature on the long-term effects of snake envenoming using different combinations of search terms. We classified conditions that last or appear more than six weeks following envenoming as long term or delayed effects of envenoming. Of 257 records identified, 51 articles describe the long-term effects of snake envenoming and were reviewed. Disability due to amputations, deformities, contracture formation, and chronic ulceration, rarely with malignant change, have resulted from local necrosis due to bites mainly from African and Asian cobras, and Central and South American Pit-vipers. Progression of acute kidney injury into chronic renal failure in Russell’s viper bites has been reported in several studies from India and Sri Lanka. Neuromuscular toxicity does not appear to result in long-term effects. -

Venom Evolution Widespread in Fishes: a Phylogenetic Road Map for the Bioprospecting of Piscine Venoms

Journal of Heredity 2006:97(3):206–217 ª The American Genetic Association. 2006. All rights reserved. doi:10.1093/jhered/esj034 For permissions, please email: [email protected]. Advance Access publication June 1, 2006 Venom Evolution Widespread in Fishes: A Phylogenetic Road Map for the Bioprospecting of Piscine Venoms WILLIAM LEO SMITH AND WARD C. WHEELER From the Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Environmental Biology, Columbia University, 1200 Amsterdam Avenue, New York, NY 10027 (Leo Smith); Division of Vertebrate Zoology (Ichthyology), American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, NY 10024-5192 (Leo Smith); and Division of Invertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, NY 10024-5192 (Wheeler). Address correspondence to W. L. Smith at the address above, or e-mail: [email protected]. Abstract Knowledge of evolutionary relationships or phylogeny allows for effective predictions about the unstudied characteristics of species. These include the presence and biological activity of an organism’s venoms. To date, most venom bioprospecting has focused on snakes, resulting in six stroke and cancer treatment drugs that are nearing U.S. Food and Drug Administration review. Fishes, however, with thousands of venoms, represent an untapped resource of natural products. The first step in- volved in the efficient bioprospecting of these compounds is a phylogeny of venomous fishes. Here, we show the results of such an analysis and provide the first explicit suborder-level phylogeny for spiny-rayed fishes. The results, based on ;1.1 million aligned base pairs, suggest that, in contrast to previous estimates of 200 venomous fishes, .1,200 fishes in 12 clades should be presumed venomous. -

The Venomous Snakes of Texas Health Service Region 6/5S

The Venomous Snakes of Texas Health Service Region 6/5S: A Reference to Snake Identification, Field Safety, Basic Safe Capture and Handling Methods and First Aid Measures for Reptile Envenomation Edward J. Wozniak DVM, PhD, William M. Niederhofer ACO & John Wisser MS. Texas A&M University Health Science Center, Institute for Biosciences and Technology, Program for Animal Resources, 2121 W Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77030 (Wozniak) City Of Pearland Animal Control, 2002 Old Alvin Rd. Pearland, Texas 77581 (Niederhofer) 464 County Road 949 E Alvin, Texas 77511 (Wisser) Corresponding Author: Edward J. Wozniak DVM, PhD, Texas A&M University Health Science Center, Institute for Biosciences and Technology, Program for Animal Resources, 2121 W Holcombe Blvd, Houston, TX 77030 [email protected] ABSTRACT: Each year numerous emergency response personnel including animal control officers, police officers, wildlife rehabilitators, public health officers and others either respond to calls involving venomous snakes or are forced to venture into the haunts of these animals in the scope of their regular duties. North America is home to two distinct families of native venomous snakes: Viperidae (rattlesnakes, copperheads and cottonmouths) and Elapidae (coral snakes) and southeastern Texas has indigenous species representing both groups. While some of these snakes are easily identified, some are not and many rank amongst the most feared and misunderstood animals on earth. This article specifically addresses all of the native species of venomous snakes that inhabit Health Service Region 6/5s and is intended to serve as a reference to snake identification, field safety, basic safe capture and handling methods and the currently recommended first aide measures for reptile envenomation. -

The Hognose Snake: a Prairie Survivor for Ten Million Years

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Programs Information: Nebraska State Museum Museum, University of Nebraska State 1977 The Hognose Snake: A Prairie Survivor for Ten Million Years M. R. Voorhies University of Nebraska State Museum, [email protected] R. G. Corner University of Nebraska State Museum Harvey L. Gunderson University of Nebraska State Museum Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/museumprogram Part of the Higher Education Administration Commons Voorhies, M. R.; Corner, R. G.; and Gunderson, Harvey L., "The Hognose Snake: A Prairie Survivor for Ten Million Years" (1977). Programs Information: Nebraska State Museum. 8. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/museumprogram/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Museum, University of Nebraska State at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Programs Information: Nebraska State Museum by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. University of Nebraska State Museum and Planetarium 14th and U Sts. NUMBER 15JAN 12, 1977 ognose snake hunting in sand. The snake uses its shovel-like snout to loosen the soil. Hognose snakes spend most of their time above ground, but burrow in search of food, primarily toads. Even when toads are buried a foot or more in sand, hog nose snakes can detect them and dig them out. (Photos by Harvey L. Gunderson) Heterodon platyrhinos. The snout is used in digging; :tivities THE HOG NOSE SNAKE hognose snakes are expert burrowers, the western species being nicknamed the "prairie rooter" by Sand hills ranchers. The snakes burrow in pursuit of food which consists Prairie Survivor for almost entirely of toads, although occasionally frogs or small birds and mammals may be eaten. -

Snakes of Durban

SNakes of durban Brown House Snake Herald Snake Non - venomous Boaedon capensis Crotaphopeltis hotamboeia Often found near human habitation where they Also referred to as the Red-lipped herald. hunt rodents, lizards and small birds. This nocturnal (active at night) snake feeds They are active at night and often collected mainlyly on frogs and is one of the more common for the pet trade. snakes found around human dwellings. SPOTTED BUSH Snake Eastern Natal Green Snake Southern Brown Egg eater Philothamnus semivariegatus Philothamnus natalensis natalensis Dasypeltis inornata Probably the most commonly found snake in This green snake is often confused with the This snake has heavily keeled body scales and urban areas. They are very good climbers, Green mamba. This diurnal species, (active during is nocturnal (active at night) . Although harmless, often seen hunting geckos and lizards the day) actively hunts frogs and geckos. they put up an impressive aggression display, in the rafters of homes. Max length 1.1 metres. with striking and open mouth gaping. Can reach This diurnal species (active during the day) over 1 metre in length and when they are that big is often confused with the Green mamba. they can eat chicken eggs. Habitat includes Max length 1.1 metres. grasslands, coastal forests and it frequents suburban gardens where they are known to enter aviaries in search of eggs. night adder Causus rhombeatus A common snake often found near ponds and dams because they feed exclusively on amphibians. They have a cytotoxic venom and bite symptoms will include pain and swelling. Max length 1 metre. -

Reptile and Amphibian Enforcement Applicable Law Sections

Reptile and Amphibian Enforcement Applicable Law Sections Environmental Conservation Law 11-0103. Definitions. As used in the Fish and Wildlife Law: 1. a. "Fish" means all varieties of the super-class Pisces. b. "Food fish" means all species of edible fish and squid (cephalopoda). c. "Migratory fish of the sea" means both catadromous and anadromous species of fish which live a part of their life span in salt water streams and oceans. d. "Fish protected by law" means fish protected, by law or by regulations of the department, by restrictions on open seasons or on size of fish that may be taken. e. Unless otherwise indicated, "Trout" includes brook trout, brown trout, red-throat trout, rainbow trout and splake. "Trout", "landlocked salmon", "black bass", "pickerel", "pike", and "walleye" mean respectively, the fish or groups of fish identified by those names, with or without one or more other common names of fish belonging to the group. "Pacific salmon" means coho salmon, chinook salmon and pink salmon. 2. "Game" is classified as (a) game birds; (b) big game; (c) small game. a. "Game birds" are classified as (1) migratory game birds and (2) upland game birds. (1) "Migratory game birds" means the Anatidae or waterfowl, commonly known as geese, brant, swans and river and sea ducks; the Rallidae, commonly known as rails, American coots, mud hens and gallinules; the Limicolae or shorebirds, commonly known as woodcock, snipe, plover, surfbirds, sandpipers, tattlers and curlews; the Corvidae, commonly known as jays, crows and magpies. (2) "Upland game birds" (Gallinae) means wild turkeys, grouse, pheasant, Hungarian or European gray-legged partridge and quail. -

Habitats Bottomland Forests; Interior Rivers and Streams; Mississippi River

hognose snake will excrete large amounts of foul- smelling waste material if picked up. Mating season occurs in April and May. The female deposits 15 to 25 eggs under rocks or in loose soil from late May to July. Hatching occurs in August or September. Habitats bottomland forests; interior rivers and streams; Mississippi River Iowa Status common; native Iowa Range southern two-thirds of Iowa Bibliography Iowa Department of Natural Resources. 2001. Biodiversity of Iowa: Aquatic Habitats CD-ROM. eastern hognose snake Heterodon platirhinos Kingdom: Animalia Division/Phylum: Chordata - vertebrates Class: Reptilia Order: Squamata Family: Colubridae Features The eastern hognose snake typically ranges from 20 to 33 inches long. Its snout is upturned with a ridge on the top. This snake may be yellow, brown, gray, olive, orange, or red. The back usually has dark blotches, but may be plain. A pair of large dark blotches is found behind the head. The underside of the tail is lighter than the belly. The scales are keeled (ridged). Its head shape is adapted for burrowing after hidden toads and it has elongated teeth used to puncture inflated toads so it can swallow them. Natural History The eastern hognose lives in areas with sandy or loose soil such as floodplains, old fields, woods, and hillsides. This snake eats toads and frogs. It is active in the day. It may overwinter in an abandoned small mammal burrow. It will flatten its head and neck, hiss, and inflate its body with air when disturbed, hence its nickname of “puff adder.” It also may vomit, flip over on its back, shudder a few times, and play dead. -

Fatal Boomslang Bite in the Northern Cape

African Journal of Emergency Medicine 9 (2019) 53–55 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect African Journal of Emergency Medicine journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/afjem CASE REPORT Fatal Boomslang bite in the Northern Cape T ⁎ Hendrik Johannes Krügera, Franz Gustav Lemkea,b, a Department of Emergency Medicine, Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe Hospital, Kimberley, South Africa b University of Cape Town, Division of Emergency Medicine, Cape Town, South Africa ABSTRACT Introduction: The authors describe an atypical presentation after a Boomslang bite with rapid progression of symptoms and death. Case report: A young gentleman was bitten and rapidly decompensated before monovalent antivenom could be administered, with fatal results. Conclusion: This case highlights the importance of having monovalent Boomslang antivenom rapidly available in all referral centres that may be involved in the management of Boomslang bite victims. African relevance which stemmed with difficulty. At 20h30, the severed head of the snake was identified by a snake • Boomslang bites are relatively uncommon in South Africa; further- expert as a juvenile female Boomslang (Dispholidus typus) – Fig. 1. more, there is little literature on the management of these poten- Various experts were consulted and concurred that the presentation was tially-fatal bites. atypical, and that, if the symptoms were due to Boomslang en- • This case study stresses the importance of early access to mono- venomation, the rapid onset was a poor prognostic sign. valent antivenom. The following treatment was recommended until monovalent anti- • The authors postulate that Boomslang venom toxicity may be dose venom could be emergently procured; the plan was initiated within 1 dependant, and therefore symptoms may progress more rapidly than hour of presentation at RMS EC: previously thought. -

Overlapping of Ranges of Eastern and Western Hognose Snakes in Southeastern Iowa

Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science Volume 78 Number 1-2 Article 11 1971 Overlapping of Ranges of Eastern and Western Hognose Snakes in Southeastern Iowa J. J. Berberich University of Iowa C. H. Dodge University of Iowa G. E. Folk Jr. University of Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©1971 Iowa Academy of Science, Inc. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pias Recommended Citation Berberich, J. J.; Dodge, C. H.; and Folk, G. E. Jr. (1971) "Overlapping of Ranges of Eastern and Western Hognose Snakes in Southeastern Iowa," Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science, 78(1-2), 25-26. Available at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pias/vol78/iss1/11 This Research is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa Academy of Science at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science by an authorized editor of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Berberich et al.: Overlapping of Ranges of Eastern and Western Hognose Snakes in So 25 Overlapping of Ranges of Eastern and Western Hognose Snakes in Southeastern Iowa J. J. BERBERICH,1 C. H. DODGE and G. E. FOLK, JR. J. J. BERBERICH, C. H . DODGE, & G. E. FOLK, JR. Overlapping ( Heterodon nasicus nasicus Baird and Girrard) is reported from of ranges of eastern and western hognose snakes in southeastern a sand prairie in Muscatine County, Iowa. Iowa. Proc. Iowa Acad. Sci., 78( 1 ) :25-26, 1971. INDEX DESCRIPTORS : hognose snake; Heterodon nasicus; H eterodon SYNOPSIS.