The Common Ownership Hypothesis: Theory and Evidence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Collective Ownership of the Earth Anna Stilz

BOOK SYMPOSIUM: ON GLOBAL JUSTICE On Collective Ownership of the Earth Anna Stilz n appealing and original aspect of Mathias Risse’s book On Global Justice is his argument for humanity’s collective ownership of the A earth. This argument focuses attention on states’ claims to govern ter- ritory, to control the resources of that territory, and to exclude outsiders. While these boundary claims are distinct from private ownership claims, they too are claims to control scarce goods. As such, they demand evaluation in terms of dis- tributive justice. Risse’s collective ownership approach encourages us to see the in- ternational system in terms of property relations, and to evaluate these relations according to a principle of distributive justice that could be justified to all humans as the earth’s collective owners. This is an exciting idea. Yet, as I argue below, more work needs to be done to develop plausible distribution principles on the basis of this approach. Humanity’s collective ownership of the earth is a complex notion. This is because the idea performs at least three different functions in Risse’s argument: first, as an abstract ideal of moral justification; second, as an original natural right; and third, as a continuing legitimacy constraint on property conventions. At the first level, collective ownership holds that all humans have symmetrical moral status when it comes to justifying principles for the distribution of earth’s original spaces and resources (that is, excluding what has been man-made). The basic thought is that whatever claims to control the earth are made, they must be compatible with the equal moral status of all human beings, since none of us created these resources, and no one specially deserves them. -

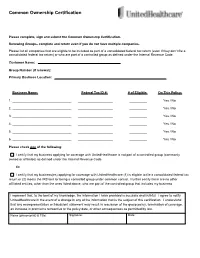

Common Ownership Form

Common Ownership Certification Please complete, sign and submit the Common Ownership Certification. Renewing Groups- complete and return even if you do not have multiple companies. Please list all companies that are eligible to be included as part of a consolidated federal tax return (even if they don’t file a consolidated federal tax return) or who are part of a controlled group as defined under the Internal Revenue Code. Customer Name: Group Number (if renewal): Primary Business Location: Business Name: Federal Tax ID #: # of Eligible: On This Policy: 1. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 2. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 3. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 4. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 5. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 6. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No Please check one of the following: I certify that my business applying for coverage with UnitedHealthcare is not part of a controlled group (commonly owned or affiliates) as defined under the Internal Revenue Code. Or I certify that my business(es) applying for coverage with UnitedHealthcare (1) is eligible to file a consolidated federal tax return or (2) meets the IRS test for being a controlled group under common control. I further certify there are no other affiliated entities, other than the ones listed above, who are part of the controlled group that includes my business. I represent that, to the best of my knowledge, the information I have provided is accurate and truthful. I agree to notify UnitedHealthcare in the event of a change in any of the information that is the subject of this certification. -

Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse

John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University Faculty Research Working Papers Series Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse Nov 2003 RWP03-044 The views expressed in the KSG Faculty Research Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or Harvard University. All works posted here are owned and copyrighted by the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism1 Mathias Risse John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University October 25, 2003 1. Left-libertarianism is not a new star on the sky of political philosophy, but it was through the recent publication of Peter Vallentyne and Hillel Steiner’s anthologies that it became clearly visible as a contemporary movement with distinct historical roots. “Left- libertarian theories of justice,” says Vallentyne, “hold that agents are full self-owners and that natural resources are owned in some egalitarian manner. Unlike most versions of egalitarianism, left-libertarianism endorses full self-ownership, and thus places specific limits on what others may do to one’s person without one’s permission. Unlike right- libertarianism, it holds that natural resources may be privately appropriated only with the permission of, or with a significant payment to, the members of society. Like right- libertarianism, left-libertarianism holds that the basic rights of individuals are ownership rights. Left-libertarianism is promising because it coherently underwrites both some demands of material equality and some limits on the permissible means of promoting this equality” (Vallentyne and Steiner (2000a), p 1; emphasis added). -

Libra Dissertation.Pdf

! ! ! ! ! On the Origin of Commons: Understanding Divergent State Preferences Over Property Rights in New Frontiers ! Catherine Shea Sanger ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy ! ! Department of Politics University of Virginia ! ! ! ! !1 of !195 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! “The first person who, having fenced off a plot of ground, took it into his head to say this is mine and found people simple enough to believe him, was the true founder of civil society.”1 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 1 Jean-Jacques Rousseau, "Discourse on the Origins and Foundations of Inequality among Men" in The First and Second Discourses, ed. Roger D. Masters, trans. Roger D. Masters and Judith Masters (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1964), p. 141 cited in Wendy Brown, Walled States, Waning Sovereignty (Cambridge, Mass.: Zone Books; Distributed by the MIT Press, 2010). 43. !2 of !195 Table of Contents ! Introduction: International Frontiers and Property Rights 5 Alternative Explanations for Variance in States’ Property Preferences 8 Methodology and Research Design 22 The First Frontier: Three Phases of High Seas Preference Formation 35 The Age of Discovery: Iberian Appropriation and Dutch-English Resistance, Late-15th – Early 17th Centuries 39 Making International Law: Anglo-Dutch Competition over the Status of European Seas, 17th Century 54 British Hegemony and Freedom of the Seas, 18th – 20th Centuries 63 Conclusion: What We’ve Learned from the Long -

Self-Ownership, Social Justice and World-Ownership Fabien Tarrit

Self-Ownership, Social Justice and World-Ownership Fabien Tarrit To cite this version: Fabien Tarrit. Self-Ownership, Social Justice and World-Ownership. Buletinul Stiintific Academia de Studii Economice di Bucuresti, Editura A.S.E, 2008, 9 (1), pp.347-355. hal-02021060 HAL Id: hal-02021060 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02021060 Submitted on 15 Feb 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Self-Ownership, Social Justice and World-Ownership TARRIT Fabien Lecturer in Economics OMI-LAME Université de Reims Champagne-Ardenne France Abstract: This article intends to demonstrate that the concept of self-ownership does not necessarily imply a justification of inequalities of condition and a vindication of capitalism, which is traditionally the case. We present the reasons of such an association, and then we specify that the concept of self-ownership as a tool in political philosophy can be used for condemning the capitalist exploitation. Keywords: Self-ownership, libertarianism, capitalism, exploitation JEL : A13, B49, B51 2 The issue of individual freedom as a stake went through the philosophical debate since the Greek antiquity. We deal with that issue through the concept of self-ownership. -

Common Ownership Community “COC”

So, are you a good neighbor? Do you know your association’s Board of Directors? Do you … ? Are you aware of when and where your association • Pay your assessments on time? meets? Have you reviewed your association’s • Abide by the rules, regulations and bylaws? bylaws? • Attend Board of Directors meetings? • Vote in elections and on critical matters? How to be a Consider getting involved. Get engaged and be aware! For additional information on Common GOOD NEIGHBOR in a Ownership Communities, please contact the • Browse your Association’s newsletter and email following: blasts, so that you have an idea of what’s going on and, so that you’ll be able to participate Office of Community Relations Common if there’s something you strongly agree or Ownership Communities disagree with. Phone: 301-952-4729 http://www.princegeorgescountymd.gov/921/ • Attend Association meetings. This will help Common-Ownership-Communities you find out what’s going on in your community and will help you become informed. You’ll FHA Resource Center have a greater influence over what happens https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/housing/ in your building or neighborhood and it’s an sfh/fharesourcectr opportunity to meet your neighbors. Office of the Attorney General Consumer At the end of the day, there is a difference between Protection Division living in a community and being a part of that Phone: 877-261-8807 particular community. While being part of an http://www.marylandattorneygeneral.gov/ Common Association can be a bit of extra work, it’s worth CPD%20Documents/Tips-Publications/ putting some effort into being a good member. -

Downloaded from Elgar Online at 09/26/2021 10:10:51PM Via Free Access

JOBNAME: EE3 Hodgson PAGE: 2 SESS: 3 OUTPUT: Thu Jun 27 12:00:07 2019 1. What does socialism mean? Under capitalism, man exploits his fellow man. Under socialism it is precisely the opposite. Eastern European joke from the Communist era1 The word socialism is modern, but the impulse behind it is ancient. The idea of holding property in common goes back to Ancient Greece and is found in the Bible.2 It has been harboured by some religions and it has been the call of radicals for centuries. In his 1516 book Utopia, Sir Thomas More imagined a system where everything was held in common ownership and internal trade was abolished. Unlike most other proposals for common ownership before the 1840s, More’s Utopia envisioned cities of between 60 000 and 100 000 adults. It is the first known proposal for what I call big socialism. Before the rise of Marxism, the predominant vision of common ownership was small-scale, rural and agricultural. It was often motivated by religious doctrine. In Germany in the 1520s the radical Protestant Thomas Müntzer proposed a Christian communism. From 1649 to 1650, during the English Civil War, the Diggers set up religious communes whose members worked together on the soil and shared its produce. There are other examples of socialism before the word was coined.3 This chapter is about the origins, meaning and evolution of the words socialism and communism. They are virtual synonyms, both largely referring to common ownership of the means of production and to the abolition of private property. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. A LeftLeft----LibertarianLibertarian Theory of Rights Arabella Millett Fisher PhD University of Edinburgh 2011 Contents Abstract....................................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements.......................................................................................................v Declaration.................................................................................................................. vi Introduction..................................................................................................................1 Part I: A Libertarian Theory of Justice...................................................................11 -

The Virtues of Common Ownership

THE VIRTUES OF COMMON OWNERSHIP ANNA DI ROBILANT∗ INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 1359 I. SANDEL’S THEORY OF JUSTICE: A “THICK REPUBLICANISM” ........... 1361 II. COMMON OWNERSHIP: LIBERAL AUTONOMY OR SUBSTANTIVE VALUES?............................................................................................ 1363 III. A NEW APPROACH TO THE COMMONS: RESOURCES, VALUES, AND ENTITLEMENTS .................................................................................. 1370 INTRODUCTION Professor Michael Sandel’s theory of justice is attractive and inspirational for lawyers interested in social change. Sandel’s call to go beyond egalitarian liberalism has real and important implications for legal and institutional engineering. For Sandel, liberal neutrality is not enough.1 To argue for equality of freedom – i.e. freedom from external coercion, freedom to materially pursue one’s ends, and freedom to form and revise one’s ends in an interpersonal context, independent of any particular conception of the good life – is not enough.2 Progressives need dare to rest their arguments for equality and their policy proposals on their substantive vision of the common good. If we agree with Sandel, we should be thinking about designing and proposing legal institutions that decidedly advance the substantive goals we care about, solidarity and fraternity for example, rather than endlessly strive to achieve liberal neutrality. Attractive and inspirational, Sandel’s theory of justice is parsimonious of recommendations for medium level institutional design. It offers little detailed guidance to private lawyers called upon to design background rules for the allocation of scarce resources and necessary burdens. In this essay, I will discuss how Sandel’s theory of justice may help orient the work of lawyers and policymakers interested in a question that is central to recent property debates: the question of the potential of common ownership for social change. -

Solidarity Co-Operatives

Solidarity co-operatives : an embedded historical communitarian pluralist approach to social enterprise development?(Keynote to RMIT Research Colloquium) RIDLEY-DUFF, Rory <http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5560-6312> and BULL, Mike Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/9890/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version RIDLEY-DUFF, Rory and BULL, Mike (2014). Solidarity co-operatives : an embedded historical communitarian pluralist approach to social enterprise development? (Keynote to RMIT Research Colloquium). In: 2014 Social Innovation and Entrepreneurship Research Colloquium, Melbourne, RMIT Building 80, 26th - 28th November 2014. (Unpublished) Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk Solidarity co-operatives: An embedded historical communitarian pluralist approach to social enterprise development? Rory Ridley-Duff and Mike Bull Rory Ridley-Duff, Reader in Co-operative and Social Enterprise, Sheffield Business School. Sheffield Hallam University, Arundel Gate, Sheffield, S1 1WB. Mike Bull, Senior Lecturer, Manchester Metropolitan University Business School, Oxford Road, Manchester M1 3GH. Rory Ridley-Duff. Sheffield Hallam University, Sheffield, S1 1WB. [email protected] Rory Ridley-Duff is Reader in Co-operative and Social Enterprise at Sheffield Business School, Sheffield Hallam University. Dr Ridley-Duff’s primary research interest is the process by which democratic relations develop in both informal and formal organisations and affect governing processes. He has authored two books, 32 scholarly papers and two novels. The first book, Emotion, Seduction and Intimacy examines relationship development at work, and the second, Understanding Social Enterprise: Theory and Practice has helped to establish the field of social enterprise studies in four continents. -

Socialism Introduction

SOS POLITICAL SCIENCE & PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION M.A POLITICAL SCIENCE II SEM POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY: MORDAN POLITICAL THOUGHT, THEORY & CONTEMPORARY IDEOLOGIES UNIT-III Topic Name-Socialism Introduction ◦Socialism is a political, social and economic philosophy encompassing a range of economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production and workers' self- management of enterprises. ... Social ownership can be public, collective, cooperative or of equity Definition ◦ In the simplest language democratic socialism means the blending of socialist and democratic methods together in order to build up an acceptable and viable political and economic structure. To put it in other words, to arrive at socialist goals through democratic means. It also denotes that as an ideology socialism is preferable to any other form such as capitalism or communism. ◦ The word socialism has been defined as “such type of socialist economy under which economic system is not only regulated by the government to ensure, welfare equity of opportunity and social justice to the people.” Who invented socialism? ◦The Communist Manifesto was written by Karl Marxand Friedrich Engels in 1848 just before the Revolutions of 1848 swept Europe, expressing what they termed scientific socialism. In the last third of the 19th century, social democratic parties arose in Europe, drawing mainly from Marxism. Types of socialism ◦ Anarcho-socialism ◦ Utopian socialism ◦ State-Communism ◦ Democratic socialism ◦ Libertarian socialism ◦ Social democratic socialism ◦ Christian socialism What is the main purpose of socialism? ◦ Socialism is a political movement that centers on changing the economic means of ownership and production. Its main objective is to foster a cooperative economy through the creation of cooperative enterprises, common ownership, state ownership or shared equity. -

New Market Socialism: a Case for Rejuvenation Or Inspired Alchemy?

NEW MARKET SOCIALISM: A CASE FOR REJUVENATION OR INSPIRED ALCHEMY? DIMITRIS MILONAKIS * ÍNDICE I. INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................................................. 2 I. EARLY MARKET SOCIALISM: THE LANGE MODEL ................................................................................... 4 II. MARKET SOCIALISM AND THE QUESTION OF KNOWLEDGE: THE AUSTRIAN CHALLENGE ............. 6 III. THE QUESTION OF INCENTIVES: MARKET SOCIALISM AND ‘NEW INFORMATION ECONOMICS’.... 7 IV. MODERN VERSIONS OF MARKET SOCIALISM ..................................................................................... 10 V. NEW MARKET SOCIALISM: A CRITIQUE FROM WITHIN........................................................................ 14 VI. TOWARDS A MORE RADICAL CRITIQUE ............................................................................................... 17 VII. BY WAY OF CONCLUSION...................................................................................................................... 21 VIII. REFERENCES ......................................................................................................................................... 22 *Department of Economics, University of Crete. I would like to thank Ben Fine for his painstaking critique of an earlier draft of this paper. My thanks also go to Costas Lapavitsas, George Argitis, the participants of the Fourth Annual Conference of the European Society for the History of Economic Thought,