Downloaded from Elgar Online at 09/26/2021 10:10:51PM Via Free Access

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Ideas and Movements That Created the Modern World

harri+b.cov 27/5/03 4:15 pm Page 1 UNDERSTANDINGPOLITICS Understanding RITTEN with the A2 component of the GCE WGovernment and Politics A level in mind, this book is a comprehensive introduction to the political ideas and movements that created the modern world. Underpinned by the work of major thinkers such as Hobbes, Locke, Marx, Mill, Weber and others, the first half of the book looks at core political concepts including the British and European political issues state and sovereignty, the nation, democracy, representation and legitimacy, freedom, equality and rights, obligation and citizenship. The role of ideology in modern politics and society is also discussed. The second half of the book addresses established ideologies such as Conservatism, Liberalism, Socialism, Marxism and Nationalism, before moving on to more recent movements such as Environmentalism and Ecologism, Fascism, and Feminism. The subject is covered in a clear, accessible style, including Understanding a number of student-friendly features, such as chapter summaries, key points to consider, definitions and tips for further sources of information. There is a definite need for a text of this kind. It will be invaluable for students of Government and Politics on introductory courses, whether they be A level candidates or undergraduates. political ideas KEVIN HARRISON IS A LECTURER IN POLITICS AND HISTORY AT MANCHESTER COLLEGE OF ARTS AND TECHNOLOGY. HE IS ALSO AN ASSOCIATE McNAUGHTON LECTURER IN SOCIAL SCIENCES WITH THE OPEN UNIVERSITY. HE HAS WRITTEN ARTICLES ON POLITICS AND HISTORY AND IS JOINT AUTHOR, WITH TONY BOYD, OF THE BRITISH CONSTITUTION: EVOLUTION OR REVOLUTION? and TONY BOYD WAS FORMERLY HEAD OF GENERAL STUDIES AT XAVERIAN VI FORM COLLEGE, MANCHESTER, WHERE HE TAUGHT POLITICS AND HISTORY. -

On Collective Ownership of the Earth Anna Stilz

BOOK SYMPOSIUM: ON GLOBAL JUSTICE On Collective Ownership of the Earth Anna Stilz n appealing and original aspect of Mathias Risse’s book On Global Justice is his argument for humanity’s collective ownership of the A earth. This argument focuses attention on states’ claims to govern ter- ritory, to control the resources of that territory, and to exclude outsiders. While these boundary claims are distinct from private ownership claims, they too are claims to control scarce goods. As such, they demand evaluation in terms of dis- tributive justice. Risse’s collective ownership approach encourages us to see the in- ternational system in terms of property relations, and to evaluate these relations according to a principle of distributive justice that could be justified to all humans as the earth’s collective owners. This is an exciting idea. Yet, as I argue below, more work needs to be done to develop plausible distribution principles on the basis of this approach. Humanity’s collective ownership of the earth is a complex notion. This is because the idea performs at least three different functions in Risse’s argument: first, as an abstract ideal of moral justification; second, as an original natural right; and third, as a continuing legitimacy constraint on property conventions. At the first level, collective ownership holds that all humans have symmetrical moral status when it comes to justifying principles for the distribution of earth’s original spaces and resources (that is, excluding what has been man-made). The basic thought is that whatever claims to control the earth are made, they must be compatible with the equal moral status of all human beings, since none of us created these resources, and no one specially deserves them. -

The Right to the Whole Produce of Labour

1RNIA SAN DIEGO THE EIGHT TO THE WHOLE PRODUCE OF LABOUR THE EIGHT TO THE WHOLE PBODUCE OF LABOUK THE ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE THEORY OF LABOUR'S CLAIM TO THE WHOLE PRODUCT OF INDUSTRY BY DK. ANTON MENGEK PROFESSOR OF JURISPRUDENCE IN THE UNIVERSITY OF VIENNA TRANSLATED BY M. E. TANNER WITH AN INTRODUCTION AND BIBLIOGRAPHY BY H. S. FOXWELL, M.A. PROFESSOR OF ECONOMICS AT UNIVERSITY COLLEGE, LONDON ; LECTURER AND LATE FELLOW OF ST. JOHN'S COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE Hontion MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 1899 A II rights reserved INTRODUCTION DR. ANTON MENGER'S remarkable study of the cardinal Dr doctrine of revolutionary socialism, now for the first W time published in English, has long enjoyed a wide reputation on the Continent; and English students of social philosophy, whether or not they are familiar with the original, will welcome its appearance in this trans- lation. The interest and importance of the subject will not be disputed, either by the opponents or the advocates of socialism ; and those who know how exceptionally Dr. Menger is qualified for work of this kind, by his juristic eminence, and his profound know- ledge of socialistic literature, will not need to be told that it has been executed with singular vigour and ability. Hitherto, perhaps because it was not generally accessible to English readers, the book has not received in this country the notice that it has met with elsewhere. Yet there are reasons why it should be of peculiar interest to English economists. The particular method of criticism adopted by Dr. -

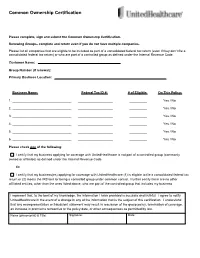

Common Ownership Form

Common Ownership Certification Please complete, sign and submit the Common Ownership Certification. Renewing Groups- complete and return even if you do not have multiple companies. Please list all companies that are eligible to be included as part of a consolidated federal tax return (even if they don’t file a consolidated federal tax return) or who are part of a controlled group as defined under the Internal Revenue Code. Customer Name: Group Number (if renewal): Primary Business Location: Business Name: Federal Tax ID #: # of Eligible: On This Policy: 1. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 2. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 3. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 4. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 5. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 6. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No Please check one of the following: I certify that my business applying for coverage with UnitedHealthcare is not part of a controlled group (commonly owned or affiliates) as defined under the Internal Revenue Code. Or I certify that my business(es) applying for coverage with UnitedHealthcare (1) is eligible to file a consolidated federal tax return or (2) meets the IRS test for being a controlled group under common control. I further certify there are no other affiliated entities, other than the ones listed above, who are part of the controlled group that includes my business. I represent that, to the best of my knowledge, the information I have provided is accurate and truthful. I agree to notify UnitedHealthcare in the event of a change in any of the information that is the subject of this certification. -

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse

John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University Faculty Research Working Papers Series Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse Nov 2003 RWP03-044 The views expressed in the KSG Faculty Research Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or Harvard University. All works posted here are owned and copyrighted by the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism1 Mathias Risse John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University October 25, 2003 1. Left-libertarianism is not a new star on the sky of political philosophy, but it was through the recent publication of Peter Vallentyne and Hillel Steiner’s anthologies that it became clearly visible as a contemporary movement with distinct historical roots. “Left- libertarian theories of justice,” says Vallentyne, “hold that agents are full self-owners and that natural resources are owned in some egalitarian manner. Unlike most versions of egalitarianism, left-libertarianism endorses full self-ownership, and thus places specific limits on what others may do to one’s person without one’s permission. Unlike right- libertarianism, it holds that natural resources may be privately appropriated only with the permission of, or with a significant payment to, the members of society. Like right- libertarianism, left-libertarianism holds that the basic rights of individuals are ownership rights. Left-libertarianism is promising because it coherently underwrites both some demands of material equality and some limits on the permissible means of promoting this equality” (Vallentyne and Steiner (2000a), p 1; emphasis added). -

Thomas Hodgskin and Economic Progress; a Radical Reconstruction of His Endogenous Growth Theory

THOMAS HODGSKIN AND ECONOMIC PROGRESS; A RADICAL RECONSTRUCTION OF HIS ENDOGENOUS GROWTH THEORY F.G. Day PhD 2009 THOMAS HODGSKIN AND ECONOMIC PROGRESS; A RADICAL RECONSTRUCTION OF HIS ENDOGENOUS GROWTH THEORY Frederick George Day A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Economics The Manchester Metropolitan University June 2009 1 Declaration I confirm that no part of this thesis has been submitted for the award of a qualification at this or any other university. 2 Abstract By means of a close reading of early 19th century economic works, and by reconstructing aspects of Thomas Hodgskin‘s political economy, this thesis presents an exposition of those parts of his work that contributed to his position on growth. Rather than concentrating on his ideas on capital, we have centred on his concept of political economy as a science concerned with labour as the sole creator of wealth. We present his political economy as having labour as its focal point within a hypothetical pure market economy. From here he sought a foundation to economic growth derived from human action rather than capital or other material circumstances. Hodgskin saw human knowledge and the use of technology as the starting point that would, from his perspective, lead inevitably to those economic conditions that produce improvements in economic welfare and by doing so allow for an increase in population. In order to demonstrate his ideas on growth, we reconstruct his concepts of what was natural and artificial to equate to the modern notions of endogenous and exogenous. -

Libra Dissertation.Pdf

! ! ! ! ! On the Origin of Commons: Understanding Divergent State Preferences Over Property Rights in New Frontiers ! Catherine Shea Sanger ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy ! ! Department of Politics University of Virginia ! ! ! ! !1 of !195 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! “The first person who, having fenced off a plot of ground, took it into his head to say this is mine and found people simple enough to believe him, was the true founder of civil society.”1 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 1 Jean-Jacques Rousseau, "Discourse on the Origins and Foundations of Inequality among Men" in The First and Second Discourses, ed. Roger D. Masters, trans. Roger D. Masters and Judith Masters (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1964), p. 141 cited in Wendy Brown, Walled States, Waning Sovereignty (Cambridge, Mass.: Zone Books; Distributed by the MIT Press, 2010). 43. !2 of !195 Table of Contents ! Introduction: International Frontiers and Property Rights 5 Alternative Explanations for Variance in States’ Property Preferences 8 Methodology and Research Design 22 The First Frontier: Three Phases of High Seas Preference Formation 35 The Age of Discovery: Iberian Appropriation and Dutch-English Resistance, Late-15th – Early 17th Centuries 39 Making International Law: Anglo-Dutch Competition over the Status of European Seas, 17th Century 54 British Hegemony and Freedom of the Seas, 18th – 20th Centuries 63 Conclusion: What We’ve Learned from the Long -

Brill's Companion to Anarchism and Philosophy

Brill’s Companion to Anarchism and Philosophy Edited by Nathan Jun LEIDEN | BOSTON For use by the Author only | © 2018 Koninklijke Brill NV Contents Editor’s Preface ix Acknowledgments xix About the Contributors xx Anarchism and Philosophy: A Critical Introduction 1 Nathan Jun 1 Anarchism and Aesthetics 39 Allan Antliff 2 Anarchism and Liberalism 51 Bruce Buchan 3 Anarchism and Markets 81 Kevin Carson 4 Anarchism and Religion 120 Alexandre Christoyannopoulos and Lara Apps 5 Anarchism and Pacifism 152 Andrew Fiala 6 Anarchism and Moral Philosophy 171 Benjamin Franks 7 Anarchism and Nationalism 196 Uri Gordon 8 Anarchism and Sexuality 216 Sandra Jeppesen and Holly Nazar 9 Anarchism and Feminism 253 Ruth Kinna For use by the Author only | © 2018 Koninklijke Brill NV viii CONTENTS 10 Anarchism and Libertarianism 285 Roderick T. Long 11 Anarchism, Poststructuralism, and Contemporary European Philosophy 318 Todd May 12 Anarchism and Analytic Philosophy 341 Paul McLaughlin 13 Anarchism and Environmental Philosophy 369 Brian Morris 14 Anarchism and Psychoanalysis 401 Saul Newman 15 Anarchism and Nineteenth-Century European Philosophy 434 Pablo Abufom Silva and Alex Prichard 16 Anarchism and Nineteenth-Century American Political Thought 454 Crispin Sartwell 17 Anarchism and Phenomenology 484 Joeri Schrijvers 18 Anarchism and Marxism 505 Lucien van der Walt 19 Anarchism and Existentialism 559 Shane Wahl Index of Proper Names 583 For use by the Author only | © 2018 Koninklijke Brill NV CHAPTER 10 Anarchism and Libertarianism Roderick T. Long Introduction -

Political Science – I

Paper code: B.A. LL.B – 110 Subject: Political Science – I Objective: This paper focuses on understanding the basic concepts, theories and functioning of State. The course prepares the student to receive instruction in Constitutional Law and Administrative Law in the context of political forces operative in society. It examines political organization, its principles (State, Law and Sovereignty) and constitutions. UNIT -I: Political Theory a. Introduction i. Political Science: Definition, Aims and Scope ii. State, Government and Law b. Theories of State i. Divine and Force Theory ii. Organic Theory iii. Idealist and Individualist Theory iv. Theory of Social Contract v. Hindu Theory: Contribution of Saptang Theory vi. Islamic Concept of State UNIT -II: Political Ideologies a. Liberalism: Concept, Elements and Criticisms; Types: Classical and Modern b. Totalitarianism: Concept, Elements and Criticisms; Types: Fascism and Nazism c. Socialism: Concept, Elements and Criticisms; Schools of Socialism: Fabianism, Syndicalism and Guild Socialism d. Marxism and Concept of State e. Feminism: Political Dimensions UNIT-III: Machinery of Government a. Constitution: Purpose, Features and classification b. Legislature: Concept, Functions and Types c. Executive: Concept, Functions and Types d. Judiciary: Concepts, Functions, Judicial Review and Independence of Judiciary e. Separation of Powers f. Political Processes UNIT- IV: Sovereignty and Citizenship a. Sovereignty: Definition and Types (Political, Popular and Legal) b. Rights: Concept and Types (Focus on Fundamental and Human Rights) c. Duties: Concept and Types d. Political Thinkers: Plato’s Justice; Aristotle on Government and Citizenship; John Rawls on Distributive Justice; Gandhi’s Concept of State and Swaraj ; Nehruvian Socialism; Jai Prakash Narain’s Total Revolution UNIT I: POLITICAL THEORY a. -

Self-Ownership, Social Justice and World-Ownership Fabien Tarrit

Self-Ownership, Social Justice and World-Ownership Fabien Tarrit To cite this version: Fabien Tarrit. Self-Ownership, Social Justice and World-Ownership. Buletinul Stiintific Academia de Studii Economice di Bucuresti, Editura A.S.E, 2008, 9 (1), pp.347-355. hal-02021060 HAL Id: hal-02021060 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02021060 Submitted on 15 Feb 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Self-Ownership, Social Justice and World-Ownership TARRIT Fabien Lecturer in Economics OMI-LAME Université de Reims Champagne-Ardenne France Abstract: This article intends to demonstrate that the concept of self-ownership does not necessarily imply a justification of inequalities of condition and a vindication of capitalism, which is traditionally the case. We present the reasons of such an association, and then we specify that the concept of self-ownership as a tool in political philosophy can be used for condemning the capitalist exploitation. Keywords: Self-ownership, libertarianism, capitalism, exploitation JEL : A13, B49, B51 2 The issue of individual freedom as a stake went through the philosophical debate since the Greek antiquity. We deal with that issue through the concept of self-ownership. -

Techno-Utopianism, Counterfeit and Real

Techno-Utopianism, Counterfeit and Real Kevin A. Carson Techno-Utopianism, Counterfeit and Real (With Special Regard to Paul Mason's Post-Capitalism) By Kevin A. Carson Center for a Stateless Society Paper No. 20 (Spring 2016) Center for a Stateless Society Too often state socialists and verticalists react dismissively to commons- based peer production and other networked, open-source visions of socialism, either failing to see any significant difference between them and the vulgar '90s dotcom hucksterism of Newt Gingrich, or worse yet seeing them as a Trojan horse for the latter. There is some superficial similarity in the rhetoric and symbols used by those respective movements. But in their essence they are very different indeed. I. Capitalist Techno-Utopianism from Daniel Bell On According to Nick Dyer-Witheford, capitalist techno-utopianism is "the immediate descendant of a concept of the late 1960s -- postindustrial society." And post-industrial society, in turn, was an outgrowth of Daniel Bell's earlier "end of ideology" thesis. Postwar affluence, the institutionalization of collective bargaining, and the welfare state had banished the class conflicts of an earlier era from the scene. [Western industrial] societies presented the successful socioeconomic model toward which other experiments, including those in the "underdeveloped" and "socialist" world, would gradually converge. This was the condition of the "end of ideology" -- which meant, in general, an end of alternatives to liberal capitalism....1 According to Bell, post-industrialism