Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Idea of the Revolution in the Nineteenth Century Pierre-Joseph Proudhon 1851

General Idea of the Revolution in the Nineteenth Century Pierre-Joseph Proudhon 1851 General Idea of the Revolution in the Nineteenth Century, by Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, was first published in French as Idée générale de la révolution au XIXe siècle. This is an electronic transcription of John Beverly Robinson's 1923 English translation, originally published in 1923 by Freedom Press, London. The text is based on Dover Publications' 2003 unabridged reproduction of Robinson's translation (ISBN 0-486-43397-8), with occasional typographical errors corrected. Table of Contents 1. To Business Men 2. General Idea of the Revolution 3. First Study. — Reaction Causes Revolution 1. The Revolutionary Force 2. Parallel Progress of the Reaction and of the Revolution Since February 3. Weakness of the Reaction. Triumph of the Revolution 4. Second Study. — Is there Sufficient Reason for Revolution in the Nineteenth Century? 1. Law of Tendency in Society. The Revolution of 1789 has done only half its work. 2. Chaos of Economic Forces. Tendency of Society toward Poverty. 3. Anomaly of Government. Tendency toward Tyranny and Corruption. 5. Third Study. — The Principle of Association 6. Fourth Study. — The Principle of Authority 1. Traditional Denial of Government. Emergence of the Idea which succeeds it. 2. General Criticism of the Idea of Authority 1. Thesis. Absolute Authority 2. Laws 3. The Constitutional Monarchy 4. Universal Suffrage 5. Direct Legislation 6. Direct Government or the Constitution of '93. Reduction to Absurdity of the Governmental Idea. 7. Fifth Study. — Social Liquidation 1. National Bank 2. The State Debt 3. Debts secured by Mortgage. Simple Obligations. -

EMMA GOLDMAN, ANARCHISM, and the “AMERICAN DREAM” by Christina Samons

AN AMERICA THAT COULD BE: EMMA GOLDMAN, ANARCHISM, AND THE “AMERICAN DREAM” By Christina Samons The so-called “Gilded Age,” 1865-1901, was a period in American his tory characterized by great progress, but also of great turmoil. The evolving social, political, and economic climate challenged the way of life that had existed in pre-Civil War America as European immigration rose alongside the appearance of the United States’ first big businesses and factories.1 One figure emerges from this era in American history as a forerunner of progressive thought: Emma Goldman. Responding, in part, to the transformations that occurred during the Gilded Age, Goldman gained notoriety as an outspoken advocate of anarchism in speeches throughout the United States and through published essays and pamphlets in anarchist newspapers. Years later, she would synthe size her ideas in collections of essays such as Anarchism and Other Essays, first published in 1917. The purpose of this paper is to contextualize Emma Goldman’s anarchist theory by placing it firmly within the economic, social, and 1 Alan M. Kraut, The Huddled Masses: The Immigrant in American Society, 1880 1921 (Wheeling, IL: Harlan Davidson, 2001), 14. 82 Christina Samons political reality of turn-of-the-twentieth-century America while dem onstrating that her theory is based in a critique of the concept of the “American Dream.” To Goldman, American society had drifted away from the ideal of the “American Dream” due to the institutionalization of exploitation within all aspects of social and political life—namely, economics, religion, and law. The first section of this paper will give a brief account of Emma Goldman’s position within American history at the turn of the twentieth century. -

What Is Counter-Economics?

What is counter-economics? Should the State cease to exist, the • Drivers in some states who do not Counter-Economy would simply be The run in front of their cars with lanterns so The Counter-Economy is the sum of all Economy. as not to scare horses; non-aggressive Human Action which is for- Other names for practicing counter- and many others. Did you find yourself on bidden by the State. Counter-economics is economists (other than black marketeers) the list? the study of the Counter-Economy andits are practices. The Counter-Economy includes • Tax evader, tax rebel, tax resister; How counter-economics works the free market, the Black Market, the • Smuggler (of Bibles to Saudi Arabia, “underground economy,” all acts of civil and drugs to New York, or humans to Califor- Suppose you can make $10,000 for social disobedience, all acts of forbidden nia); each shipment (or whatever counter-eco- association (sexual, racial, cross-religious), • Trucker convoys; nomic act), and you can perform ten a and anything else the State, at any place or • Pornographers, prostitutes, procur- month. Once a month, someone in your line time, chooses to prohibit, control, regulate, ers, and other sexual entrepreneurs; gets arrested. You have 23 competitors. Half tax, or tariff. The Counter-Economy ex- • Gold bugs, food hoarders, windfall are convicted, half of them lose all their cludes all State-approved action (the “White profiteers, and others who refuse to believe appeals and are forced to pay a fine of half Market”) and the Red Market (violence and official economic mysticism; a million dollars and spend six months in theftnotapproved by the State). -

UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Making Popular and Solidarity Economies in Dollarized Ecuador: Money, Law, and the Social After Neoliberalism Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3xx5n43g Author Nelms, Taylor Campbell Nahikian Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Making Popular and Solidarity Economies in Dollarized Ecuador: Money, Law, and the Social After Neoliberalism DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Anthropology by Taylor Campbell Nahikian Nelms Dissertation Committee: Professor Bill Maurer, Chair Associate Professor Julia Elyachar Professor George Marcus 2015 Portion of Chapter 1 © 2015 John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All other materials © 2015 Taylor Campbell Nahikian Nelms TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv CURRICULUM VITAE vii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION xi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: “The Problem of Delimitation”: Expertise, Bureaucracy, and the Popular 51 and Solidarity Economy in Theory and Practice CHAPTER 2: Saving Sucres: Money and Memory in Post-Neoliberal Ecuador 91 CHAPTER 3: Dollarization, Denomination, and Difference 139 INTERLUDE: On Trust 176 CHAPTER 4: Trust in the Social 180 CHAPTER 5: Law, Labor, and Exhaustion 216 CHAPTER 6: Negotiable Instruments and the Aesthetics of Debt 256 CHAPTER 7: Interest and Infrastructure 300 WORKS CITED 354 ii LIST OF FIGURES Page Figure 1 Field Sites and Methods 49 Figure 2 Breakdown of Interviewees 50 Figure 3 State Institutions of the Popular and Solidarity Economy in Ecuador 90 Figure 4 A Brief Summary of Four Cajas (and an Association), as of January 2012 215 Figure 5 An Emic Taxonomy of Debt Relations (Bárbara’s Portfolio) 299 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Every anthropologist seems to have a story like this one. -

Making Sense of the Barro-Ricardo Equivalence in a Financialized World

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Esposito, Lorenzo; Mastromatteo, Giuseppe Working Paper Defaultnomics: Making sense of the Barro-Ricardo equivalence in a financialized world Working Paper, No. 933 Provided in Cooperation with: Levy Economics Institute of Bard College Suggested Citation: Esposito, Lorenzo; Mastromatteo, Giuseppe (2019) : Defaultnomics: Making sense of the Barro-Ricardo equivalence in a financialized world, Working Paper, No. 933, Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, NY This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/209176 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen -

Liberty Magazine January 1995.Pdf Mime Type

The Bell Curve, Stupidity, and January 1995 Vol. 8, No.3 $4.00 You ~ ,.';.\, . ~00 . c Libertarian Bestsellers autographed by their authors - the ideal holiday gift! Investment Biker The story of a legendary Wall Street investor's·travels around the world by motorcycle, searching out new investments and adventures. "One of the most broadly appealing libertarian books ever published." -R.W. Bradford, LffiERTY ... autographed by the author, Jim Rogers. (402 pp.) $25.00 hard cover. Crisis Investing for the Rest of the '90s This perceptive classic updated for today's investor! "Creative metaphors; hilarious, pithy anecdotes; innovative graphic analyses." -Victor Niederhoffer, LffiERTY ... autographed by the author, Douglas Casey. (444 pp.) $22.50 hard cover. It Carne froIn Arkansas David Boaz, Karl Hess, Douglas Casey, Randal O'Toole, Harry Browne, Durk Pearson, Sandy Shaw, and others skewer the Clinton administration ... autographed by the editor, R.W. Bradford. (180 pp.) $12.95 soft cover. We the Living (First Russian Edition) Ayn Rand's classic novel ofRussia translated into Russian. A collector's item ... autographed by the translator, Dimitry Costygin. (542 pp.) $19.95 hard cover. The God of the Machine Isabel Paterson's classic defense of freedom, with a new introduction by Stephen Cox. Autographed by the editor. (366 pp.) $21.95 soft cover. Fuzzy Thinking: The New Science of Fuzzy Logic A mind-bending meditation on the new revolution in computer intelligence - and on the nature of science, philosophy, and reality ... autographed by the author, Bart Kosko. (318 pp.) $12.95 soft cover. Freedorn of Informed Choice: The FDA vs Nutrient Supplements A well-informed expose of America's pharmaceutical "fearocracy." The authors' "'split label' proposal makes great r----------------------------,sense." -Milton Friedman .. -

Ancap Conversion Therapy

AnCap Conversion Therapy By @ C ats A nd K alash Introduction This is a list of videos, essays, and books to introduce AnCaps and other Right-Libertarians to Left- Libertarianism. Not ALL opinions held by the listed authors and creators reflect my personal beliefs. My intention with this document is to provide enough introductory resources to dispel misconceptions Right- Libertarians may have about the left and allow them to see things from a more left-wing perspective. Yes the title is a little cheeky but it’s all in good fun. I ask any Right-Libertarians who come across this document view the listed content with an open mind. I think it’s important we all try to scrutinize our own beliefs and ask ourselves if our current positions are truly consistent with the values we hold, values of liberty, justice, etc. I also ask that you don’t watch just one video and come to a conclusion, this is a list for a reason. You don’t have to read/watch everything in one sitting, you can bookmark or download the list and come back to different parts of it later. What is Left-Libertarianism? “Left-Libertarianism” can be used to refer to different things, but in the context of this document it refers to a specific group of ideologies or tendencies which heavily revolve around Libertarian values and to varying extents, free markets. Mutualism, Individualist-Anarchism, and Agorism can all be considered “Left-Libertarian” tendencies. Some may also include Georgism and Left-Rothbardianism in that list as well. -

Download As a PDF File

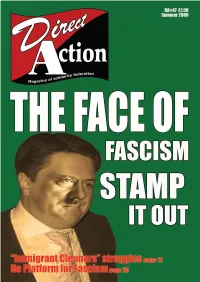

Direct Action www.direct-action.org.uk Summer 2009 Direct Action is published by the Aims of the Solidarity Federation Solidarity Federation, the British section of the International Workers he Solidarity Federation is an organi- isation in all spheres of life that conscious- Association (IWA). Tsation of workers which seeks to ly parallel those of the society we wish to destroy capitalism and the state. create; that is, organisation based on DA is edited & laid out by the DA Col- Capitalism because it exploits, oppresses mutual aid, voluntary cooperation, direct lective & printed by Clydeside Press and kills people, and wrecks the environ- democracy, and opposed to domination ([email protected]). ment for profit worldwide. The state and exploitation in all forms. We are com- Views stated in these pages are not because it can only maintain hierarchy and mitted to building a new society within necessarily those of the Direct privelege for the classes who control it and the shell of the old in both our workplaces Action Collective or the Solidarity their servants; it cannot be used to fight and the wider community. Unless we Federation. the oppression and exploitation that are organise in this way, politicians – some We do not publish contributors’ the consequences of hierarchy and source claiming to be revolutionary – will be able names. Please contact us if you want of privilege. In their place we want a socie- to exploit us for their own ends. to know more. ty based on workers’ self-management, The Solidarity Federation consists of locals solidarity, mutual aid and libertarian com- which support the formation of future rev- munism. -

Why America Needs a Second Party by Harold Meyerson INSIDE DEMOCRATIC LEFT Dsaction

PUBLISHED BY THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALISTS OF AMERICA Why America Needs A Second Party By Harold Meyerson INSIDE DEMOCRATIC LEFT DSAction ... 11 Why We Need a Second Party Jimmy Higgins Reports ... 16 by Harold Meyerson ... 3 Turning Rage Into Action: Daring To Be Ambitious: New York City DSA Commentary on the Clarence Thomas Hearings Organizes to Elect a Progressive City Council by Suzanne Crowell ... 13 by Miriam Bensman ... 6 Book Review: Guy Molyneux reviews E.J. Dionne's Why Americans Hate Politics ... 14 On TheLefJ Canadian Health Care Speakers Tour Report ... 8 Cover photo by Robert Fox/Impact Visuals EDITORIAL West European social democracies. In bachev is correct to want those "inter SOVI ET the Soviet Union, he'd like to see similar esting results" in democracy, economic welfare state guarantees, active labor development, and human rights that market policies, and government in- are inspired by the socialist idea. In tervention in the economy for both this respect, he's in tune with the DREAMER growth and equity. In his heart of citizens of his country since polls con hearts, Gorby wants his country to sistently show widespread support by Joanne Barkan look like Sweden in good times. among them for welfare state guaran- Dream on -- James Baker would tees. If George Bush would stop ex The coup in the Soviet Union fails. certainly respond. And democratic so- porting his models of misery, what's The train of history is back on the cialists everywhere would have to admit worked best for the West Europeans reform track -- for the moment. Re that the economic resources and insti- might -- with time and aid -- work for publics of the former empire declare tutional mechanisms just don't exist the East. -

Libertarian Feminism: Can This Marriage Be Saved? Roderick Long Charles Johnson 27 December 2004

Libertarian Feminism: Can This Marriage Be Saved? Roderick Long Charles Johnson 27 December 2004 Let's start with what this essay will do, and what it will not. We are both convinced of, and this essay will take more or less for granted, that the political traditions of libertarianism and feminism are both in the main correct, insightful, and of the first importance in any struggle to build a just, free, and compassionate society. We do not intend to try to justify the import of either tradition on the other's terms, nor prove the correctness or insightfulness of the non- aggression principle, the libertarian critique of state coercion, the reality and pervasiveness of male violence and discrimination against women, or the feminist critique of patriarchy. Those are important conversations to have, but we won't have them here; they are better found in the foundational works that have already been written within the feminist and libertarian traditions. The aim here is not to set down doctrine or refute heresy; it's to get clear on how to reconcile commitments to both libertarianism and feminism—although in reconciling them we may remove some of the reasons that people have had for resisting libertarian or feminist conclusions. Libertarianism and feminism, when they have encountered each other, have most often taken each other for polar opposites. Many 20th century libertarians have dismissed or attacked feminism—when they have addressed it at all—as just another wing of Left-wing statism; many feminists have dismissed or attacked libertarianism—when they have addressed it at all—as either Angry White Male reaction or an extreme faction of the ideology of the liberal capitalist state. -

Libertarian Party at Sea on Land

Libertarian Party at Sea on Land To Mom who taught me the Golden Rule and Henry George 121 years ahead of his time and still counting Libertarian Party at Sea on Land Author: Harold Kyriazi Book ISBN: 978-1-952489-02-0 First Published 2000 Robert Schalkenbach Foundation Official Publishers of the works of Henry George The Robert Schalkenbach Foundation (RSF) is a private operating foundation, founded in 1925, to promote public awareness of the social philosophy and economic reforms advocated by famed 19th century thinker and activist, Henry George. Today, RSF remains true to its founding doctrine, and through efforts focused on education, communities, outreach, and publishing, works to create a world in which all people are afforded the basic necessities of life and the natural world is protected for generations to come. ROBERT SCHALKENBACH FOUND ATION Robert Schalkenbach Foundation [email protected] www.schalkenbach.org Libertarian Party at Sea on Land By Harold Kyriazi ROBERT SCHALKENBACH FOUNDATION New York City 2020 Acknowledgments Dan Sullivan, my longtime fellow Pittsburgher and geo-libertarian, not only introduced me to this subject about seven years ago, but has been a wonderful teacher and tireless consultant over the years since then. I’m deeply indebted to him, and appreciative of his steadfast efforts to enlighten his fellow libertarians here in Pittsburgh and elsewhere. Robin Robertson, a fellow geo-libertarian whom I met at the 1999 Council of Georgist Organizations Conference, gave me detailed constructive criticism on an early draft, brought Ayn Rand’s essay on the broadcast spectrum to my attention, helped conceive the cover illustration, and helped in other ways too numerous to mention. -

Filósofos O Viajeros: El Pensamiento Como Extravío

Astrolabio. Revista internacional de filosofía Año 2009. Núm. 8. ISSN 1699-7549. 16-32 pp. Towards a Reconciliation of Public and Private Autonomy in Thoreau’s ‘Hybrid’ Politics Antonio Casado da Rocha1 Resumen: Tras una revisión bibliográfica, el artículo proporciona una presentación de la filosofía política de Henry D. Thoreau, enfatizando en su obra un concepto de autodeterminación cívica que Habermas descompone en una autonomía pública y otra privada. Sostengo que Thoreau no era un anarquista antisocial, ni tampoco un mero liberal individualista, sino que su liberalismo presenta elementos propios de la teoría democrática e incluso del comunitarismo político. Finalmente, identifico y describo una tensión entre esos temas liberales y democráticos, tanto en la obra de Thoreau como en la vida política de las sociedades occidentales, mostrando así la relevancia de este autor. Palabras clave: Filosofía política, democracia, liberalismo, literatura norteamericana del siglo XIX Abstract: After a literature review, this paper provides an overview of Henry D. Thoreau’s political philosophy, with emphasis on the concept of civil self-determination, which Habermas sees as comprised of both private and public autonomy, and which is present in Thoreau’s own work. I argue that he was not an anti-social anarchist, or even a pure liberal individualist, but that along with the main liberal themes of his thought there is also a democratic, even communitarian strand. Finally, I identify and describe a tension between democratic and liberal themes in both his work and contemporary Western politics, thus highlighting Thoreau’s relevance. Key-words: Political philosophy, democracy, liberalism, 19th century North American literature According to Stanley Cavell (2005, pp.