Liberty, Property and Rationality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Causes and Consequences of the Inflation Taxi

Causes and Consequences of the Inflation Taxi Abstract: While ethical implications of direct taxation systems have recently received renewed attention, a more veiled scheme remains unnoticed: the inflation tax. We overview the causes of inflation, and assess its consequences. Salient wealth redistributions are a defining feature of inflation, as savers and fixed income individuals see a relative wealth reduction. While evasion of this tax is difficult in many instances due to the primacy of money in a monetary economy, the tax codes of most developed countries allow avoidance techniques to be employed. We analyze the ways that inflation taxes may be avoided in an attempt to preserve personal wealth, as well as the consequences of such practices. 1 Causes and Consequences of the Inflation Tax Introduction Much recent literature focuses on the ethics of direct taxation (Joel Slemrod 2007; Bagus et al. 2011; Robert W. McGee 2012c). Whether income and consumption taxes are coercively imposed on both consumers and producers has long been contested. Being this as it may, taxes can be, and often are, remitted to the government voluntarily as if they were not reliant on their coercive imposition. In this case we are led to believe that there is no difference between taxation and voluntarily donations of money to the government –both will result in spending that is consistent with taxpayers’ desires. The curiosity that arises is that if people did not donate money voluntarily to the government, neither coercion nor taxation would be necessary.ii However, the degree of “voluntariness” of the governing process implementing taxation cannot affect the core nature of the problem (Robert McGee 1994). -

Chapter 4 Freedom and Progress

Chapter 4 Freedom and Progress The best road to progress is freedom’s road. John F. Kennedy The only freedom which deserves the name, is that of pursuing our own good in our own way, so long as we do not attempt to deprive others of theirs, or impeded their efforts to obtain it. John Stuart Mill To cull the inestimable benefits assured by freedom of the press, it is necessary to put up with the inevitable evils springing therefrom. Alexis de Tocqueville Freedom is necessary to generate progress; people also value freedom as an important component of progress. This chapter will contend that both propositions are correct. Without liberty, there will be little or no progress; most people will consider an expansion in freedom as progress. Neither proposition would win universal acceptance. Some would argue that a totalitarian state can marshal the resources to generate economic growth. Many will contend that too much liberty induces libertine behavior and is destructive of society, peace, and the family. For better or worse, the record shows that freedom has increased throughout the world over the last few centuries and especially over the last few decades. There are of course many examples of non-free, totalitarian, ruthless government on the globe, but their number has decreased and now represents a smaller proportion of the world’s population. Perhaps this growth of freedom is partially responsible for the breakdown of the family and the rise in crime, described in the previous chapter. Dictators do tolerate less crime and are often very repressive of deviant sexual behavior, but, as the previous chapter reported, divorce and illegitimacy are more connected with improved income of women than with a permissive society. -

Economic Freedom” and Economic Growth: Questioning the Claim That Freer Markets Make Societies More Prosperous

Munich Personal RePEc Archive “Economic freedom” and economic growth: questioning the claim that freer markets make societies more prosperous Cohen, Joseph N City University of New York, Queens College 27 September 2011 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/33758/ MPRA Paper No. 33758, posted 27 Sep 2011 18:38 UTC “Economic Freedom” and Economic Growth: Questioning the Claim that Freer Markets Make Societies More Prosperous Joseph Nathan Cohen Department of Sociology City University of New York, Queens College 65-30 Kissena Blvd. Flushing, New York 11367 [email protected] Abstract A conventional reading of economic history implies that free market reforms rescued the world’s economies from stagnancy during the 1970s and 1980s. I reexamine a well-established econometric literature linking economic freedom to growth, and argue that their positive findings hinge on two problems: conceptual conflation and ahistoricity. When these criticisms are taken seriously, a very different view of the historical record emerges. There does not appear to be enduring relationship between economic liberalism and growth. Much of the observed relationship between these two variables involves a one-shot transition to freer markets around the Cold War’s end. Several concurrent changes took place in this historical context, and it is hasty to conclude that it was market liberalization alone that produced the economic turnaround of the 1990s and early-2000s. I also question market fundamentalists’ view that all forms of liberalization are helpful, arguing that the data show little to no benefit from reforms that did not attract foreign investment. Word Count: 6,698 (excl. -

Review of Murray N. Rothbard's an Austrian

Reason Papers 97 Murray N. Rothbard, An Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic Thought, Vol. i & ii (Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publ., Ltd., 1995), pp.576 & 544; Index; $99.95 each. Parth Shah, University of Michigan, Dearborn I have always enjoyed Professor Rothbard's talks at various Austrian conferences and seminars, especially the ones on the history of economic thought. That subject itself, I think, brought out all the qualities that made Professor Rothbard such a loving and towering figure in Austrian and libertarian circles; his incredible breadth of knowledge, diligent scholarship, disarming sense of humor, perspective coalescing of personal with social and intellectual history, genuine respect for a worthy adversary, and yes, his unwavering dedication to praxeology and liberty. Professor Rothbard's two volumes on the history of thought more than meet the expectations; they encapsulate all those unique qualities of his. It makes it all the more unfortunate that the volumes cover the period only up to about 1870. Taking his cue from his mentor Joseph Dorfman, Professor Rothbard eschews the "Few Great Men approach" (talking about the already anointed), and focuses on the "'lesser' figures... emphasizing the importance of their religious and social philosophies as well as their narrower strictly 'economic' views" (1, p.xii). With Thomas Kuhn's realistic appraisal of the path of progress in science in terms of paradigm shifts, Professor Rothbard dismisses the Whig theory of history and works with no presumption that "later thought is better than earlier" (1, p.x). The acceptance of the zig-zag path of the progress of the discipline promises us "far more human drama than is usually offered in histories of economic thought." (1, p.xiii). -

Free to Choose Video Tape Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt1n39r38j No online items Inventory to the Free to Choose video tape collection Finding aid prepared by Natasha Porfirenko Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2008 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Inventory to the Free to Choose 80201 1 video tape collection Title: Free to Choose video tape collection Date (inclusive): 1977-1987 Collection Number: 80201 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 10 manuscript boxes, 10 motion picture film reels, 42 videoreels(26.6 Linear Feet) Abstract: Motion picture film, video tapes, and film strips of the television series Free to Choose, featuring Milton Friedman and relating to laissez-faire economics, produced in 1980 by Penn Communications and television station WQLN in Erie, Pennsylvania. Includes commercial and master film copies, unedited film, and correspondence, memoranda, and legal agreements dated from 1977 to 1987 relating to production of the series. Digitized copies of many of the sound and video recordings in this collection, as well as some of Friedman's writings, are available at http://miltonfriedman.hoover.org . Creator: Friedman, Milton, 1912-2006 Creator: Penn Communications Creator: WQLN (Television station : Erie, Pa.) Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 1980, with increments received in 1988 and 1989. -

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

Liberty Magazine January 1995.Pdf Mime Type

The Bell Curve, Stupidity, and January 1995 Vol. 8, No.3 $4.00 You ~ ,.';.\, . ~00 . c Libertarian Bestsellers autographed by their authors - the ideal holiday gift! Investment Biker The story of a legendary Wall Street investor's·travels around the world by motorcycle, searching out new investments and adventures. "One of the most broadly appealing libertarian books ever published." -R.W. Bradford, LffiERTY ... autographed by the author, Jim Rogers. (402 pp.) $25.00 hard cover. Crisis Investing for the Rest of the '90s This perceptive classic updated for today's investor! "Creative metaphors; hilarious, pithy anecdotes; innovative graphic analyses." -Victor Niederhoffer, LffiERTY ... autographed by the author, Douglas Casey. (444 pp.) $22.50 hard cover. It Carne froIn Arkansas David Boaz, Karl Hess, Douglas Casey, Randal O'Toole, Harry Browne, Durk Pearson, Sandy Shaw, and others skewer the Clinton administration ... autographed by the editor, R.W. Bradford. (180 pp.) $12.95 soft cover. We the Living (First Russian Edition) Ayn Rand's classic novel ofRussia translated into Russian. A collector's item ... autographed by the translator, Dimitry Costygin. (542 pp.) $19.95 hard cover. The God of the Machine Isabel Paterson's classic defense of freedom, with a new introduction by Stephen Cox. Autographed by the editor. (366 pp.) $21.95 soft cover. Fuzzy Thinking: The New Science of Fuzzy Logic A mind-bending meditation on the new revolution in computer intelligence - and on the nature of science, philosophy, and reality ... autographed by the author, Bart Kosko. (318 pp.) $12.95 soft cover. Freedorn of Informed Choice: The FDA vs Nutrient Supplements A well-informed expose of America's pharmaceutical "fearocracy." The authors' "'split label' proposal makes great r----------------------------,sense." -Milton Friedman .. -

Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas Sargent, ,, ^ Neil Wallace (P

Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas Sargent, ,, ^ Neil Wallace (p. 1) District Conditions (p.18) Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review vol. 5, no 3 This publication primarily presents economic research aimed at improving policymaking by the Federal Reserve System and other governmental authorities. Produced in the Research Department. Edited by Arthur J. Rolnick, Richard M. Todd, Kathleen S. Rolfe, and Alan Struthers, Jr. Graphic design and charts drawn by Phil Swenson, Graphic Services Department. Address requests for additional copies to the Research Department. Federal Reserve Bank, Minneapolis, Minnesota 55480. Articles may be reprinted if the source is credited and the Research Department is provided with copies of reprints. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis or the Federal Reserve System. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Quarterly Review/Fall 1981 Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic Thomas J. Sargent Neil Wallace Advisers Research Department Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis and Professors of Economics University of Minnesota In his presidential address to the American Economic in at least two ways. (For simplicity, we will refer to Association (AEA), Milton Friedman (1968) warned publicly held interest-bearing government debt as govern- not to expect too much from monetary policy. In ment bonds.) One way the public's demand for bonds particular, Friedman argued that monetary policy could constrains the government is by setting an upper limit on not permanently influence the levels of real output, the real stock of government bonds relative to the size of unemployment, or real rates of return on securities. -

Forms of Government

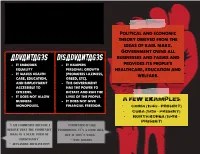

communism An economic ideology Political and economic theory derived from the ideas of karl marx. Government owns all Advantages DISAdvantages businesses and farms and - It embodies - It hampers provides its people's equality personal growth healthcare, education and - It makes health (promotes laziness, welfare. care, education, greed, etc). and employment - The government accessible to has the power to citizens. dictate and run the - It does not allow lives of the people. business - It does not give A Few Examples: monopolies. financial freedom. - China (1949 – Present) - Cuba (1959 – Present) - North Korea (1948 – Present) “I am communist because I “Communism is like believe that the comMunist prohibition. It’s a good idea, ideal is a state form of but it won’t work.” christianity” - will Rogers - Alexander Zhuravlyovv Socialism Government owns many of An Economic Ideology the larger industries and provide education, health and welfare services while Advantages DISAdvantages allowing citizens some - There is a balance - Bureaucracy hampers economic choices between wealth and the delivery of earnings services. - There is equal access - People are to health care and unmotivated to A Few Examples: education develop Vietnam - It breaks down social entrepreneurial skills. Laos barriers - The government has Denmark too much control Finland “The meaning of peace is “Socialism is workable only the absence of opposition to in heaven where it isn’t need socialism” and in where they’ve got it.” - Karl Marx - Cecil Palmer Capitalism Free-market -

Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse

John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University Faculty Research Working Papers Series Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse Nov 2003 RWP03-044 The views expressed in the KSG Faculty Research Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or Harvard University. All works posted here are owned and copyrighted by the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism1 Mathias Risse John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University October 25, 2003 1. Left-libertarianism is not a new star on the sky of political philosophy, but it was through the recent publication of Peter Vallentyne and Hillel Steiner’s anthologies that it became clearly visible as a contemporary movement with distinct historical roots. “Left- libertarian theories of justice,” says Vallentyne, “hold that agents are full self-owners and that natural resources are owned in some egalitarian manner. Unlike most versions of egalitarianism, left-libertarianism endorses full self-ownership, and thus places specific limits on what others may do to one’s person without one’s permission. Unlike right- libertarianism, it holds that natural resources may be privately appropriated only with the permission of, or with a significant payment to, the members of society. Like right- libertarianism, left-libertarianism holds that the basic rights of individuals are ownership rights. Left-libertarianism is promising because it coherently underwrites both some demands of material equality and some limits on the permissible means of promoting this equality” (Vallentyne and Steiner (2000a), p 1; emphasis added). -

Libertarian Feminism: Can This Marriage Be Saved? Roderick Long Charles Johnson 27 December 2004

Libertarian Feminism: Can This Marriage Be Saved? Roderick Long Charles Johnson 27 December 2004 Let's start with what this essay will do, and what it will not. We are both convinced of, and this essay will take more or less for granted, that the political traditions of libertarianism and feminism are both in the main correct, insightful, and of the first importance in any struggle to build a just, free, and compassionate society. We do not intend to try to justify the import of either tradition on the other's terms, nor prove the correctness or insightfulness of the non- aggression principle, the libertarian critique of state coercion, the reality and pervasiveness of male violence and discrimination against women, or the feminist critique of patriarchy. Those are important conversations to have, but we won't have them here; they are better found in the foundational works that have already been written within the feminist and libertarian traditions. The aim here is not to set down doctrine or refute heresy; it's to get clear on how to reconcile commitments to both libertarianism and feminism—although in reconciling them we may remove some of the reasons that people have had for resisting libertarian or feminist conclusions. Libertarianism and feminism, when they have encountered each other, have most often taken each other for polar opposites. Many 20th century libertarians have dismissed or attacked feminism—when they have addressed it at all—as just another wing of Left-wing statism; many feminists have dismissed or attacked libertarianism—when they have addressed it at all—as either Angry White Male reaction or an extreme faction of the ideology of the liberal capitalist state. -

Libertarian Party at Sea on Land

Libertarian Party at Sea on Land To Mom who taught me the Golden Rule and Henry George 121 years ahead of his time and still counting Libertarian Party at Sea on Land Author: Harold Kyriazi Book ISBN: 978-1-952489-02-0 First Published 2000 Robert Schalkenbach Foundation Official Publishers of the works of Henry George The Robert Schalkenbach Foundation (RSF) is a private operating foundation, founded in 1925, to promote public awareness of the social philosophy and economic reforms advocated by famed 19th century thinker and activist, Henry George. Today, RSF remains true to its founding doctrine, and through efforts focused on education, communities, outreach, and publishing, works to create a world in which all people are afforded the basic necessities of life and the natural world is protected for generations to come. ROBERT SCHALKENBACH FOUND ATION Robert Schalkenbach Foundation [email protected] www.schalkenbach.org Libertarian Party at Sea on Land By Harold Kyriazi ROBERT SCHALKENBACH FOUNDATION New York City 2020 Acknowledgments Dan Sullivan, my longtime fellow Pittsburgher and geo-libertarian, not only introduced me to this subject about seven years ago, but has been a wonderful teacher and tireless consultant over the years since then. I’m deeply indebted to him, and appreciative of his steadfast efforts to enlighten his fellow libertarians here in Pittsburgh and elsewhere. Robin Robertson, a fellow geo-libertarian whom I met at the 1999 Council of Georgist Organizations Conference, gave me detailed constructive criticism on an early draft, brought Ayn Rand’s essay on the broadcast spectrum to my attention, helped conceive the cover illustration, and helped in other ways too numerous to mention.