Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Collective Ownership of the Earth Anna Stilz

BOOK SYMPOSIUM: ON GLOBAL JUSTICE On Collective Ownership of the Earth Anna Stilz n appealing and original aspect of Mathias Risse’s book On Global Justice is his argument for humanity’s collective ownership of the A earth. This argument focuses attention on states’ claims to govern ter- ritory, to control the resources of that territory, and to exclude outsiders. While these boundary claims are distinct from private ownership claims, they too are claims to control scarce goods. As such, they demand evaluation in terms of dis- tributive justice. Risse’s collective ownership approach encourages us to see the in- ternational system in terms of property relations, and to evaluate these relations according to a principle of distributive justice that could be justified to all humans as the earth’s collective owners. This is an exciting idea. Yet, as I argue below, more work needs to be done to develop plausible distribution principles on the basis of this approach. Humanity’s collective ownership of the earth is a complex notion. This is because the idea performs at least three different functions in Risse’s argument: first, as an abstract ideal of moral justification; second, as an original natural right; and third, as a continuing legitimacy constraint on property conventions. At the first level, collective ownership holds that all humans have symmetrical moral status when it comes to justifying principles for the distribution of earth’s original spaces and resources (that is, excluding what has been man-made). The basic thought is that whatever claims to control the earth are made, they must be compatible with the equal moral status of all human beings, since none of us created these resources, and no one specially deserves them. -

Ideological Contributions of Celtic Freedom and Individualism to Human Rights

chapter 4 Ideological Contributions of Celtic Freedom and Individualism to Human Rights This chapter emphasizes the importance of the often-overlooked contribu- tions of indigenous European cultures to the development of human rights. Attention is given to the ancient Celtic culture, the ideas of Celtic freedom and individualism, the distinctive role of the Scottish theologian, John Dunn Scotus and the Scottish Arbroath Declaration of Freedom (1320).1 It is from the Scottish Enlightenment and its subsequent influence on the late 18th century revolutions that we see an affirmative declaration of the Rights of Man, which is a precursor to the development of modern human rights. The importance of the Celtic-Irish-Scottish contribution to human rights is that it was the foun- dation for individual liberty and dignity in Western civilization. Indigenous Celtic culture staked an original and critical claim to the ideal of universal hu- man dignity. This is an important insight because it broadens the ideals that promote human rights, including within them those ideals of the indigenous cultures of the world, whose voices are oftentimes forgotten. It strengthens the universality of human rights. i The Intellectual and Philosophical Origins of International Law and Human Rights The intellectual and philosophical origins of human rights rhetoric and law, democracy, freedom and ideas supporting “consent of the governed” are in- tertwined in this composite explanation that attempts to explain all of these themes with the historical themes of Roman natural law, Athenian democracy and later the modern political philosophy of John Locke and his followers. The absence of a medieval connection between the alleged ancient Roman and Greek sources and the modern developments of human rights indicates that this perspective is faulty. -

Analysis Note: the Economic Case for Gender Equality

Analysis Note: the Economic Case for Gender Equality Mark SMITH and Francesca BETTIO August 2008 This analysis note was financed by and prepared for the use of the European Commission, Directorate- General for Employment, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities. It does not necessarily reflect the opinion or position of the European Commission, Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities. Neither the Commission nor any person acting on its behalf is responsible for the use that might be made of the information contained in this publication. EGGE – European Commission's Network of Experts on Employment and Gender Equality issues – Fondazione Giacomo Brodolini EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Although gender equality is widely regarded as a worthwhile goal it is also seen as having potential costs or even acting as a constraint on economic growth and while this view may not be evident in official policy it remains implicit in policy decisions. For example, where there is pressure to increase the quantity of work or promote growth, progress towards gender equality may be regarded as something that can be postponed. However, it is possible to make an Economic Case for gender equality, as an investment, such that it can be regarded as a means to promote growth and employment rather than act as a cost or constraint. As such equality policies need to be seen in a wider perspective with a potentially greater impact on individuals, firms, regions and nations. The Economic Case for gender equality can be regarded as going a step further than the so- called Business Case. While the Business Case emphasises the need for equal treatment to reflect the diversity among potential employees and an organisation’s customers the Economic Case stresses economic benefits at a macro level. -

Libertarianism, Culture, and Personal Predispositions

Undergraduate Journal of Psychology 22 Libertarianism, Culture, and Personal Predispositions Ida Hepsø, Scarlet Hernandez, Shir Offsey, & Katherine White Kennesaw State University Abstract The United States has exhibited two potentially connected trends – increasing individualism and increasing interest in libertarian ideology. Previous research on libertarian ideology found higher levels of individualism among libertarians, and cross-cultural research has tied greater individualism to making dispositional attributions and lower altruistic tendencies. Given this, we expected to observe positive correlations between the following variables in the present research: individualism and endorsement of libertarianism, individualism and dispositional attributions, and endorsement of libertarianism and dispositional attributions. We also expected to observe negative correlations between libertarianism and altruism, dispositional attributions and altruism, and individualism and altruism. Survey results from 252 participants confirmed a positive correlation between individualism and libertarianism, a marginally significant positive correlation between libertarianism and dispositional attributions, and a negative correlation between individualism and altruism. These results confirm the connection between libertarianism and individualism observed in previous research and present several intriguing questions for future research on libertarian ideology. Key Words: Libertarianism, individualism, altruism, attributions individualistic, made apparent -

Diogenes Laertius, Vitae Philosophorum, Book Five

Binghamton University The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB) The Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy Newsletter 12-1986 The Lives of the Peripatetics: Diogenes Laertius, Vitae Philosophorum, Book Five Michael Sollenberger Mount St. Mary's University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://orb.binghamton.edu/sagp Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Ancient Philosophy Commons, and the History of Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Sollenberger, Michael, "The Lives of the Peripatetics: Diogenes Laertius, Vitae Philosophorum, Book Five" (1986). The Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy Newsletter. 129. https://orb.binghamton.edu/sagp/129 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in The Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy Newsletter by an authorized administrator of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. f\îc|*zx,e| lîâ& The Lives of the Peripatetics: Diogenes Laertius, Vitae Philosoohorum Book Five The biographies of six early Peripatetic philosophers are con tained in the fifth book of Diogenes Laertius* Vitae philosoohorum: the lives of the first four heads of the sect - Aristotle, Theophras tus, Strato, and Lyco - and those of two outstanding members of the school - Demetrius of Phalerum and Heraclides of Pontus, For the history of two rival schools, the Academy and the Stoa, we are for tunate in having not only Diogenes' versions in 3ooks Four and Seven, but also the Index Academicorum and the Index Stoicorum preserved among the papyri from Herculaneum, But for the Peripatos there-is no such second source. -

What Is There in Anarchy for Woman?

Interview in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch Sunday Magazine, October 24, 1897 What Is There in Anarchy for Woman? By Emma Goldman. "What does anarchy hold out to me--a woman?" "More to woman than to anyone else--everything which she has not--freedom and equality." Quickly, earnestly Emma Goldman, the priestess of anarchy, exiled from Russia, feared by police, and now a guest of St. Louis Anarchists,1 gave this answer to my question. I found her at No. 1722 Oregon avenue, an old-style two-story brick house, the home of a sympathizer2-- not a relative as has been stated. I was received by a good-natured, portly German woman, and taken back to a typical German dining- room--everything clean and neat as soap and water could make them. After carefully dusting a chair for me with her apron, she took my name back to the bold little free-thinker. I was welcome. I found Emma Goldman sipper her coffee and partaking of bread and jelly, as her morning's repast. She was neatly clad in a percale shirt waist and skirt, with white collar and cuffs, her feet encased in a loose pair of cloth slippers. She doesn't look like a Russian Nihilist who will be sent to Siberia if she ever crosses the frontier of her native land. "Do you believe in marriage?" I asked. "I do not," answered the fair little Anarchist, as promptly as before. "I believe that when two people love each other that no judge, minister, or court, or body of people, have anything to do with it. -

25 Mill on Justice and Rights DAVID O

25 Mill on Justice and Rights DAVID O. BRINK Mill develops his account of the juridical concepts of justice and rights in several d ifferent contexts and works. He discusses both the logic of these juridical concepts – what rights and justice are and how they are related to each other and to utility – and their substance – what rights we have and what justice demands. Though the logic and substance of these juridical concepts are distinct, they are related. An account of the logic of rights and justice should constrain how one justifies claims about their substance, and ways of defending what rights we have and what justice demands pre- suppose claims about the logic of these concepts. We would do well to examine Mill’s central claims about the substance of justice and rights before turning to his views about their logic. Mill links demands of justice and individual rights. He defends rights to basic liberties in On Liberty (1859), women’s rights to sexual equality as a matter of justice in The Subjection of Women (1869), and rights to fair equality opportunity in Principles of Political Economy (1848) and The Subjection of Women. While these are Mill’s central claims about the substance of rights and justice, he is attracted to three different conceptions of the logic of rights and justice. His most explicit discussion occurs in Chapter V of Utilitarianism (1861) in response to the worry that justice is a moral con- cept independent of considerations of utility. There, Mill develops claims about justice and rights that treat them as related parts of an indirect utilitarian conception of duty that explains fundamental moral notions in terms of expedient sanctioning responses. -

Anarchy Alive! Anti-Authoritarian Politics from Practice to Theory

Anarchy Alive! Anti-authoritarian Politics from Practice to Theory URI GORDON Pluto P Press LONDON • ANN ARBOR, MI GGordonordon 0000 pprere iiiiii 225/9/075/9/07 113:04:293:04:29 First published 2008 by Pluto Press 345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA and 839 Greene Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48106 www.plutobooks.com Copyright © Uri Gordon 2008 The right of Uri Gordon to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Hardback ISBN-13 978 0 7453 2684 9 ISBN-10 0 7453 2684 6 Paperback ISBN-13 978 0 7453 2683 2 ISBN-10 0 7453 2683 8 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data applied for This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Designed and produced for Pluto Press by Chase Publishing Services Ltd, Fortescue, Sidmouth, EX10 9QG, England Typeset from disk by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England Printed and bound in the European Union by CPI Antony Rowe Ltd, Chippenham and Eastbourne, England GGordonordon 0000 pprere iivv 225/9/075/9/07 113:04:293:04:29 Contents Acknowledgements vi Introduction 1 1 What Moves the Movement? Anarchism as a Political Culture 11 2 Anarchism Reloaded Network Convergence and Political Content 28 3 Power and Anarchy In/equality + In/visibility in Autonomous Politics 47 4 Peace, Love and Petrol Bombs Anarchism and Violence Revisited 78 5 Luddites, Hackers and Gardeners Anarchism and the Politics of Technology 109 6 HomeLand Anarchy and Joint Struggle in Palestine/Israel 139 7 Conclusion 163 Bibliography 165 Index 180 GGordonordon 0000 pprere v 225/9/075/9/07 113:04:293:04:29 Acknowledgements This book began its unlikely life as my doctoral project at Oxford University. -

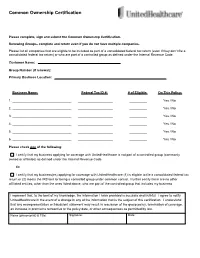

Common Ownership Form

Common Ownership Certification Please complete, sign and submit the Common Ownership Certification. Renewing Groups- complete and return even if you do not have multiple companies. Please list all companies that are eligible to be included as part of a consolidated federal tax return (even if they don’t file a consolidated federal tax return) or who are part of a controlled group as defined under the Internal Revenue Code. Customer Name: Group Number (if renewal): Primary Business Location: Business Name: Federal Tax ID #: # of Eligible: On This Policy: 1. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 2. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 3. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 4. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 5. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 6. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No Please check one of the following: I certify that my business applying for coverage with UnitedHealthcare is not part of a controlled group (commonly owned or affiliates) as defined under the Internal Revenue Code. Or I certify that my business(es) applying for coverage with UnitedHealthcare (1) is eligible to file a consolidated federal tax return or (2) meets the IRS test for being a controlled group under common control. I further certify there are no other affiliated entities, other than the ones listed above, who are part of the controlled group that includes my business. I represent that, to the best of my knowledge, the information I have provided is accurate and truthful. I agree to notify UnitedHealthcare in the event of a change in any of the information that is the subject of this certification. -

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

Individual and Collective Information Acquisition: an Experimental Study

Individual and Collective Information Acquisition: An Experimental Study∗ P¨ellumb Reshidi† Alessandro Lizzeri‡ Leeat Yariv§ Jimmy Chan¶ Wing Suen‖ September 2020 Abstract Many committees|juries, political task forces, etc.|spend time gathering costly information before reaching a decision. We report results from lab experiments focused on such information- collection processes. We consider decisions governed by individuals and groups and compare how voting rules affect outcomes. We also contrast static information collection, as in classical hypothesis testing, with dynamic collection, as in sequential hypothesis testing. Generally, out- comes approximate the theoretical benchmark and sequential information collection is welfare enhancing relative to static collection. Nonetheless, several important departures emerge. Static information collection is excessive, and sequential information collection is non-stationary, pro- ducing declining decision accuracies over time. Furthermore, groups using majority rule yield especially hasty and inaccurate decisions. ∗We thank Roland Benabou, Stephen Morris, Salvo Nunnari, and Wolfgang Pesendorfer for very helpful discussions and feedback. We gratefully acknowledge the support of NSF grants SES-1629613 and SES-1949381. †Department of Economics, Princeton University [email protected] ‡Department of Economics, Princeton University [email protected] §Department of Economics, Princeton University [email protected] ¶Department of Economics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong [email protected] ‖Faculty of Business and Economics, University of Hong Kong [email protected] 1 1 Introduction 1.1 Overview Juries, boards of directors, congressional and university committees, government agencies such as the FDA or the EPA, and many other committees spend time deliberating issues before reaching a decision or issuing a recommendation. An important component of such collective decisions is the acquisition of information. -

ANTI-AUTHORITARIAN INTERVENTIONS in DEMOCRATIC THEORY by BRIAN CARL BERNHARDT B.A., James Madison University, 2005 M.A., University of Colorado at Boulder, 2010

BEYOND THE DEMOCRATIC STATE: ANTI-AUTHORITARIAN INTERVENTIONS IN DEMOCRATIC THEORY by BRIAN CARL BERNHARDT B.A., James Madison University, 2005 M.A., University of Colorado at Boulder, 2010 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Political Science 2014 This thesis entitled: Beyond the Democratic State: Anti-Authoritarian Interventions in Democratic Theory written by Brian Carl Bernhardt has been approved for the Department of Political Science Steven Vanderheiden, Chair Michaele Ferguson David Mapel James Martel Alison Jaggar Date The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. Bernhardt, Brian Carl (Ph.D., Political Science) Beyond the Democratic State: Anti-Authoritarian Interventions in Democratic Theory Thesis directed by Associate Professor Steven Vanderheiden Though democracy has achieved widespread global popularity, its meaning has become increasingly vacuous and citizen confidence in democratic governments continues to erode. I respond to this tension by articulating a vision of democracy inspired by anti-authoritarian theory and social movement practice. By anti-authoritarian, I mean a commitment to individual liberty, a skepticism toward centralized power, and a belief in the capacity of self-organization. This dissertation fosters a conversation between an anti-authoritarian perspective and democratic theory: What would an account of democracy that begins from these three commitments look like? In the first two chapters, I develop an anti-authoritarian account of freedom and power.