This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Ideas and Movements That Created the Modern World

harri+b.cov 27/5/03 4:15 pm Page 1 UNDERSTANDINGPOLITICS Understanding RITTEN with the A2 component of the GCE WGovernment and Politics A level in mind, this book is a comprehensive introduction to the political ideas and movements that created the modern world. Underpinned by the work of major thinkers such as Hobbes, Locke, Marx, Mill, Weber and others, the first half of the book looks at core political concepts including the British and European political issues state and sovereignty, the nation, democracy, representation and legitimacy, freedom, equality and rights, obligation and citizenship. The role of ideology in modern politics and society is also discussed. The second half of the book addresses established ideologies such as Conservatism, Liberalism, Socialism, Marxism and Nationalism, before moving on to more recent movements such as Environmentalism and Ecologism, Fascism, and Feminism. The subject is covered in a clear, accessible style, including Understanding a number of student-friendly features, such as chapter summaries, key points to consider, definitions and tips for further sources of information. There is a definite need for a text of this kind. It will be invaluable for students of Government and Politics on introductory courses, whether they be A level candidates or undergraduates. political ideas KEVIN HARRISON IS A LECTURER IN POLITICS AND HISTORY AT MANCHESTER COLLEGE OF ARTS AND TECHNOLOGY. HE IS ALSO AN ASSOCIATE McNAUGHTON LECTURER IN SOCIAL SCIENCES WITH THE OPEN UNIVERSITY. HE HAS WRITTEN ARTICLES ON POLITICS AND HISTORY AND IS JOINT AUTHOR, WITH TONY BOYD, OF THE BRITISH CONSTITUTION: EVOLUTION OR REVOLUTION? and TONY BOYD WAS FORMERLY HEAD OF GENERAL STUDIES AT XAVERIAN VI FORM COLLEGE, MANCHESTER, WHERE HE TAUGHT POLITICS AND HISTORY. -

On Collective Ownership of the Earth Anna Stilz

BOOK SYMPOSIUM: ON GLOBAL JUSTICE On Collective Ownership of the Earth Anna Stilz n appealing and original aspect of Mathias Risse’s book On Global Justice is his argument for humanity’s collective ownership of the A earth. This argument focuses attention on states’ claims to govern ter- ritory, to control the resources of that territory, and to exclude outsiders. While these boundary claims are distinct from private ownership claims, they too are claims to control scarce goods. As such, they demand evaluation in terms of dis- tributive justice. Risse’s collective ownership approach encourages us to see the in- ternational system in terms of property relations, and to evaluate these relations according to a principle of distributive justice that could be justified to all humans as the earth’s collective owners. This is an exciting idea. Yet, as I argue below, more work needs to be done to develop plausible distribution principles on the basis of this approach. Humanity’s collective ownership of the earth is a complex notion. This is because the idea performs at least three different functions in Risse’s argument: first, as an abstract ideal of moral justification; second, as an original natural right; and third, as a continuing legitimacy constraint on property conventions. At the first level, collective ownership holds that all humans have symmetrical moral status when it comes to justifying principles for the distribution of earth’s original spaces and resources (that is, excluding what has been man-made). The basic thought is that whatever claims to control the earth are made, they must be compatible with the equal moral status of all human beings, since none of us created these resources, and no one specially deserves them. -

Ryley, Peter. "The English Individualists." Making Another World Possible: Anarchism, Anti- Capitalism and Ecology in Late 19Th and Early 20Th Century Britain

Ryley, Peter. "The English individualists." Making Another World Possible: Anarchism, Anti- Capitalism and Ecology in Late 19th and Early 20th Century Britain. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013. 51–86. Contemporary Anarchist Studies. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 24 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501306754.ch-003>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 24 September 2021, 12:22 UTC. Copyright © Peter Ryley 2013. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 3 The English individualists There is a conventional historical narrative that portrays the incremental growth of collectivist political economy as something promoted and fought for by popular movements, an almost inevitable part of the process of industrial modernization. Whether described in class terms as the ‘forward march of labour’ or ideologically as the rise of socialism, the narrative is broadly the same. The old certainties had to give way in the face of modern mass societies. This poses no problem for anarcho-communism. It can be accommodated comfortably on the libertarian wing of collectivism. But what of individualism? It seems out of place, a curiosity; the last gasp of a liberal England that was about to die. Perhaps that explains its comparative neglect. Yet seen as part of the radical milieu of the time, it seems neither anomalous nor a fringe movement. It stood firmly in the tradition of a left libertarian radicalism that was a serious competitor of the collectivist left. There were two main groupings of individualists in late Victorian Britain. -

Unit 5 Equality

UNIT 5 EQUALITY Structure 5.1 Introduction 5.2 Equality vs. Inequality 5.2.1 Struggle for Equality 5.3 What is Equality? 5.4 Dimensions of Equality 5.4.1 Legal Equality 5.4.2 Political Equality 5.4.3 Economic Equality 5.4.4 Social Equality 5.5 Relation of Equality with Liberty and Justice 5.5.1 Equality and Liberty As Opposed To Each Other 5.5.2 Equality and Liberty Are Complementary To Each Other 5.5.3 Equality and Justice 5.6 Towards Equality 5.7 Plea for Inequality in the Contemporary World 5.8 Marxist Concept of Equality 5.9 Summary 5.10 Exercises 5.1 INTRODUCTION Of all the basic concepts of social, economic, moral and political philosophy, none is more confusing and baffling than the concept of equality because it figures in all other concepts like justice, liberty, rights, property, etc. During the last two thousand years, many dimensions of equality have been elaborated by Greeks, Stoics, Christian fathers who separately and collectively stressed on its one or the other aspect. Under the impact of liberalism and Marxism, equality acquired an altogether different connotation. Contemporary social movements like feminism, environmentalism are trying to give a new meaning to this concept. Basically, equality is a value and a principle essentially modern and progressive. Though the debate about equality has been going on for centuries, the special feature of modern societies is that we no longer take inequality for granted or something natural. Equality is also used as a measure of what is modern and the whole process of modernisation in the form of political egalitarianism. -

Participatory Economics & the Next System

Created by Matt Caisley from the Noun Project Participatory Economics & the Next System By Robin Hahnel Introduction It is increasingly apparent that neoliberal capitalism is not working well for most of us. Grow- ing inequality of wealth and income is putting the famous American middle class in danger of becoming a distant memory as American children, for the first time in our history, now face economic prospects worse than what their parents enjoyed. We suffer from more frequent financial “shocks” and linger in recession far longer than in the past. Education and health care systems are being decimated. And if all this were not enough, environmental destruction continues to escalate as we stand on the verge of triggering irreversible, and perhaps cataclys- mic, climate change. yst w s em p e s n s o l s a s i s b o i l p iCreated by Matt Caisley o fromt the Noun Project r ie s & p However, in the midst of escalating economic dysfunction, new economic initia- tives are sprouting up everywhere. What these diverse “new” or “future” economy initiatives have in common is that they reject the economics of competition and greed and aspire instead to develop an economics of equitable cooperation that is environmentally sustainable. What they also have in common is that they must survive in a hostile economic environment.1 Helping these exciting and hopeful future economic initiatives grow and stay true to their principles will require us to think more clearly about what kind of “next system” these initiatives point toward. It is in this spirit -

Me, Myself & Mine: the Scope of Ownership

ME, MYSELF & MINE The Scope of Ownership _________________________________ PETER MARTIN JAWORSKI _________________________________ May, 2012 Committee: Fred Miller (Chair) David Shoemaker, Steven Wall, Daniel Jacobson, Neil Englehart ii ABSTRACT This dissertation is an attempt to defend the following thesis: The scope of legitimate ownership claims is much more narrow than what Lockean liberals have traditionally thought. Firstly, it is more narrow with respect to the particular claims that are justified by Locke’s labour- mixing argument. It is more difficult to come to own things in the first place. Secondly, it is more narrow with respect to the kinds of things that are open to the ownership relation. Some things, like persons and, maybe, cultural artifacts, are not open to the ownership relation but are, rather, fit objects for the guardianship, in the case of the former, and stewardship, in the case of the latter, relationship. To own, rather than merely have a property in, some object requires the liberty to smash, sell, or let spoil the object owned. Finally, the scope of ownership claims appear to be restricted over time. We can lose our claims in virtue of a change in us, a change that makes it the case that we are no longer responsible for some past action, like the morally interesting action required for justifying ownership claims. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: Much of this work has benefited from too many people to list. However, a few warrant special mention. My committee, of course, deserves recognition. I’m grateful to Fred Miller for his many, many hours of pouring over my various manuscripts and rough drafts. -

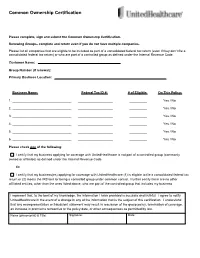

Common Ownership Form

Common Ownership Certification Please complete, sign and submit the Common Ownership Certification. Renewing Groups- complete and return even if you do not have multiple companies. Please list all companies that are eligible to be included as part of a consolidated federal tax return (even if they don’t file a consolidated federal tax return) or who are part of a controlled group as defined under the Internal Revenue Code. Customer Name: Group Number (if renewal): Primary Business Location: Business Name: Federal Tax ID #: # of Eligible: On This Policy: 1. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 2. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 3. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 4. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 5. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 6. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No Please check one of the following: I certify that my business applying for coverage with UnitedHealthcare is not part of a controlled group (commonly owned or affiliates) as defined under the Internal Revenue Code. Or I certify that my business(es) applying for coverage with UnitedHealthcare (1) is eligible to file a consolidated federal tax return or (2) meets the IRS test for being a controlled group under common control. I further certify there are no other affiliated entities, other than the ones listed above, who are part of the controlled group that includes my business. I represent that, to the best of my knowledge, the information I have provided is accurate and truthful. I agree to notify UnitedHealthcare in the event of a change in any of the information that is the subject of this certification. -

Political Science 270 Mechanisms of International Relations

Political Science 270 Mechanisms of International Relations Hein Goemans Course Information: Harkness 337 Spring 2016 Office Hours: Wed. 2 { 3 PM 16:50{19:30 Wednesday [email protected] Meliora 203 The last fifteen years or so saw a major revolution in the social sciences. Instead of trying to discover and test grand \covering laws" that have universal validity and tremendous scope| think Newton's gravity or Einstein's relativity|the social sciences are in the process of switch- ing to more narrow and middle-range theories and explanations, often referred to as causal mechanisms. Recently, however, a new so-called \behavioral" approach { often but not always complementary { is currently sweeping the field. Since mechanisms remain the core theoretical building blocks in our field, we will continue to focus on them. In the bulk of this course students will be introduced to a range of such causal mechanisms with applications in international relations. Although these causal mechanisms can loosely be described in prose, explicit formalization { e.g., math { allows for a much deeper and richer understanding of the phenomena of study. In other words, formalization enables simplification and thus a better understanding of what is \really" going on. To set us on that path, we begin with some very basic rational choice fundamentals to introduce you to formal models in a rigorous way to show the power and potential of this approach. In other words, there will be some *gasp* Algebra. For much of the very brief but essential introduction to game theory we will use William Spaniel's Channel (http://gametheory101.com/courses/game-theory-101/, also on YouTube), as well as his cheap but very highly rated introductory book Game Theory 101: The Complete Textbook available at Amazon (http://www.amazon.com). -

Chapter 18 County Budgets and Fiscal Control

CHAPTER 18 COUNTY BUDGETS AND FISCAL CONTROL Last Revision September, 2010 18.01 INTRODUCTION Balancing the Budget Ohio counties and other local political subdivisions are required by state law to adopt a budget resolution annually. Along with other local governmental entities, Ohio’s counties should adopt proper financial accounting, budgeting, and taxing standards as part of the requirement to maintain their fiscal integrity. 1 The basic outline of the county budget process is set by state law. Each board of county commissioners is required to pass an annual appropriation measure based on a “tax budget” that certifies that tax revenues and other receipts and resources will be sufficient to meet planned expenditures. It should be noted that ORC Section 5705.281 allows the county budget commission to waive the tax budget, and a number of counties have implemented this authority. For those counties that have waived the tax budget, the county budget commission may require the commissioners to provide other information during the budget process. See Section 18.10 for additional information. Counties maintain a variety of funds that support their programs and services. Budgeting by fund is a distinguishing feature of the public sector. State law recognizes 1 The roles and responsibilities of county offices are discussed in Section 18.02 of this Chapter, as well as in Chapter 1, and in the respective chapters of this Handbook , which are referred to in Chapter 1. 1 that balancing a county’s operating budget for each fund is at the heart of sound fiscal management. The following passage from the Ohio Revised Code (ORC) contains this fundamental requirement of balancing each fund within a county’s budget: The total appropriations from each fund shall not exceed the total of the estimated revenue available for expenditure therefrom, as certified by the budget commission, or in case of appeal, by the board of tax appeals. -

Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse

John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University Faculty Research Working Papers Series Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse Nov 2003 RWP03-044 The views expressed in the KSG Faculty Research Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or Harvard University. All works posted here are owned and copyrighted by the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism1 Mathias Risse John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University October 25, 2003 1. Left-libertarianism is not a new star on the sky of political philosophy, but it was through the recent publication of Peter Vallentyne and Hillel Steiner’s anthologies that it became clearly visible as a contemporary movement with distinct historical roots. “Left- libertarian theories of justice,” says Vallentyne, “hold that agents are full self-owners and that natural resources are owned in some egalitarian manner. Unlike most versions of egalitarianism, left-libertarianism endorses full self-ownership, and thus places specific limits on what others may do to one’s person without one’s permission. Unlike right- libertarianism, it holds that natural resources may be privately appropriated only with the permission of, or with a significant payment to, the members of society. Like right- libertarianism, left-libertarianism holds that the basic rights of individuals are ownership rights. Left-libertarianism is promising because it coherently underwrites both some demands of material equality and some limits on the permissible means of promoting this equality” (Vallentyne and Steiner (2000a), p 1; emphasis added). -

A History of Maryland's Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016

A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 Published by: Maryland State Board of Elections Linda H. Lamone, Administrator Project Coordinator: Jared DeMarinis, Director Division of Candidacy and Campaign Finance Published: October 2016 Table of Contents Preface 5 The Electoral College – Introduction 7 Meeting of February 4, 1789 19 Meeting of December 5, 1792 22 Meeting of December 7, 1796 24 Meeting of December 3, 1800 27 Meeting of December 5, 1804 30 Meeting of December 7, 1808 31 Meeting of December 2, 1812 33 Meeting of December 4, 1816 35 Meeting of December 6, 1820 36 Meeting of December 1, 1824 39 Meeting of December 3, 1828 41 Meeting of December 5, 1832 43 Meeting of December 7, 1836 46 Meeting of December 2, 1840 49 Meeting of December 4, 1844 52 Meeting of December 6, 1848 53 Meeting of December 1, 1852 55 Meeting of December 3, 1856 57 Meeting of December 5, 1860 60 Meeting of December 7, 1864 62 Meeting of December 2, 1868 65 Meeting of December 4, 1872 66 Meeting of December 6, 1876 68 Meeting of December 1, 1880 70 Meeting of December 3, 1884 71 Page | 2 Meeting of January 14, 1889 74 Meeting of January 9, 1893 75 Meeting of January 11, 1897 77 Meeting of January 14, 1901 79 Meeting of January 9, 1905 80 Meeting of January 11, 1909 83 Meeting of January 13, 1913 85 Meeting of January 8, 1917 87 Meeting of January 10, 1921 88 Meeting of January 12, 1925 90 Meeting of January 2, 1929 91 Meeting of January 4, 1933 93 Meeting of December 14, 1936 -

Concepts of Inequality Development Issues No

Development Strategy and Policy Analysis Unit w Development Policy and Analysis Division Department of Economic and Social Affairs Concepts of Inequality Development Issues No. 1 21 October 2015 Inequality—the state of not being equal, especially in status, rights, and opportunities1—is a concept very much at the heart Summary of social justice theories. However, it is prone to confusion in public debate as it tends to mean different things to different The understanding of inequality has evolved from the people. Some distinctions are common though. Many authors traditional outcome-oriented view, whereby income is distinguish “economic inequality”, mostly meaning “income used as a proxy for well-being. The opportunity-oriented inequality”, “monetary inequality” or, more broadly, inequality perspective acknowledges that circumstances of birth are in “living conditions”. Others further distinguish a rights-based, essential to life outcomes and that equality of opportunity legalistic approach to inequality—inequality of rights and asso- requires a fair starting point for all. ciated obligations (e.g. when people are not equal before the law, or when people have unequal political power). Concerning economic inequality, much of the discussion has on poverty reduction. Pro-poor growth approaches made their boiled down to two views. One is chiefly concerned with the debut and growth and equity (through income redistribution) inequality of outcomes in the material dimensions of well-being were seen as separate policy instruments, each capable of address- and that may be the result of circumstances beyond one’s control ing poverty. The central concern was in raising the incomes of (ethnicity, family background, gender, and so on) as well as talent poor households.