Self-Ownership, Social Justice and World-Ownership Fabien Tarrit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Collective Ownership of the Earth Anna Stilz

BOOK SYMPOSIUM: ON GLOBAL JUSTICE On Collective Ownership of the Earth Anna Stilz n appealing and original aspect of Mathias Risse’s book On Global Justice is his argument for humanity’s collective ownership of the A earth. This argument focuses attention on states’ claims to govern ter- ritory, to control the resources of that territory, and to exclude outsiders. While these boundary claims are distinct from private ownership claims, they too are claims to control scarce goods. As such, they demand evaluation in terms of dis- tributive justice. Risse’s collective ownership approach encourages us to see the in- ternational system in terms of property relations, and to evaluate these relations according to a principle of distributive justice that could be justified to all humans as the earth’s collective owners. This is an exciting idea. Yet, as I argue below, more work needs to be done to develop plausible distribution principles on the basis of this approach. Humanity’s collective ownership of the earth is a complex notion. This is because the idea performs at least three different functions in Risse’s argument: first, as an abstract ideal of moral justification; second, as an original natural right; and third, as a continuing legitimacy constraint on property conventions. At the first level, collective ownership holds that all humans have symmetrical moral status when it comes to justifying principles for the distribution of earth’s original spaces and resources (that is, excluding what has been man-made). The basic thought is that whatever claims to control the earth are made, they must be compatible with the equal moral status of all human beings, since none of us created these resources, and no one specially deserves them. -

Libertarianism, Culture, and Personal Predispositions

Undergraduate Journal of Psychology 22 Libertarianism, Culture, and Personal Predispositions Ida Hepsø, Scarlet Hernandez, Shir Offsey, & Katherine White Kennesaw State University Abstract The United States has exhibited two potentially connected trends – increasing individualism and increasing interest in libertarian ideology. Previous research on libertarian ideology found higher levels of individualism among libertarians, and cross-cultural research has tied greater individualism to making dispositional attributions and lower altruistic tendencies. Given this, we expected to observe positive correlations between the following variables in the present research: individualism and endorsement of libertarianism, individualism and dispositional attributions, and endorsement of libertarianism and dispositional attributions. We also expected to observe negative correlations between libertarianism and altruism, dispositional attributions and altruism, and individualism and altruism. Survey results from 252 participants confirmed a positive correlation between individualism and libertarianism, a marginally significant positive correlation between libertarianism and dispositional attributions, and a negative correlation between individualism and altruism. These results confirm the connection between libertarianism and individualism observed in previous research and present several intriguing questions for future research on libertarian ideology. Key Words: Libertarianism, individualism, altruism, attributions individualistic, made apparent -

Diogenes Laertius, Vitae Philosophorum, Book Five

Binghamton University The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB) The Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy Newsletter 12-1986 The Lives of the Peripatetics: Diogenes Laertius, Vitae Philosophorum, Book Five Michael Sollenberger Mount St. Mary's University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://orb.binghamton.edu/sagp Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Ancient Philosophy Commons, and the History of Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Sollenberger, Michael, "The Lives of the Peripatetics: Diogenes Laertius, Vitae Philosophorum, Book Five" (1986). The Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy Newsletter. 129. https://orb.binghamton.edu/sagp/129 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in The Society for Ancient Greek Philosophy Newsletter by an authorized administrator of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. f\îc|*zx,e| lîâ& The Lives of the Peripatetics: Diogenes Laertius, Vitae Philosoohorum Book Five The biographies of six early Peripatetic philosophers are con tained in the fifth book of Diogenes Laertius* Vitae philosoohorum: the lives of the first four heads of the sect - Aristotle, Theophras tus, Strato, and Lyco - and those of two outstanding members of the school - Demetrius of Phalerum and Heraclides of Pontus, For the history of two rival schools, the Academy and the Stoa, we are for tunate in having not only Diogenes' versions in 3ooks Four and Seven, but also the Index Academicorum and the Index Stoicorum preserved among the papyri from Herculaneum, But for the Peripatos there-is no such second source. -

The Costs and Benefits of Government Control: Evidence from China's Collectively-Owned Enterprises Jiangyong Lu /Peking Unive

The Costs and Benefits of Government Control: Evidence from China’s Collectively-Owned Enterprises Jiangyong Lu /Peking Universitya Zhigang Tao/University of Hong Kongb Zhi Yang/Hua Zhong University of Science & Technologyc May 2009 Abstract: China’s collectively-owned enterprises are unconventional, as they are nominally owned by those people residing in the areas where the enterprises are located but effectively controlled by the local governments. This study finds that collectively-owned enterprises, once being privatized, encounter an increase in the cost of goods sold to sales ratio but manage to lower down the managerial expenses to sales ratio. The findings imply that local government officials may help collectively-owned enterprises gain access to cheaper production inputs, but they may use those enterprises to pursue private benefits, thereby shedding lights on the costs and benefits of government control. JEL classification codes: L33, P31, D23 Keywords: China’s collectively-owned enterprises, costs and benefits of government control, managerial expenses, and cost of goods sold a Department of Strategic Management, Guanghua School of Management, Peking University, Beijing, P.R.China. Email: [email protected] b School of Business, and School of Economics and Finance, University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam Road, Hong Kong. Email: [email protected] c School of Management, Huazhong University of Science & Technology, Wuhan, P.R. China. Email: [email protected] The Costs and Benefits of Government Control: Evidence from China’s Collectively-Owned Enterprises May 2009 Abstract: China’s collectively-owned enterprises are unconventional, as they are nominally owned by those people residing in the areas where the enterprises are located but effectively controlled by the local governments. -

Self-Reliance by Ralph Waldo Emerson in His Essay

Self-Reliance by Ralph Waldo Emerson In his essay “Self-Reliance,” Emerson begins with a definition of genius, a quality which he says he recently encountered in a poem written by an eminent painter. Genius is to “believe your own thought, to believe that what is true for you in your private heart is true for all men.” Moses, Plato, and Milton had this quality of disregarding tradition and speaking their own thoughts, but most people dismiss these thoughts, only to recognize them later in works of acknowledged genius. At some point, every individual realizes that “imitation is suicide.” One’s own powers of perception and creativity are the most important gifts, and one can only be happy by putting one’s heart into the work at hand. Great individuals have always accepted their position in the age in which they lived and trusted their own ability to make the best of it. Children, and even animals, also have this enviable power of certitude in their undivided minds. Society requires conformity from its citizens, but to be a self-reliant individual is to be a nonconformist. “Nothing is at last sacred but the integrity of your own mind.” Concepts such as good and evil, with which many people are accustomed to label their thoughts, are meaningless so long as people are true to themselves. Most people are swayed by irrelevant matters, such as how their conduct appears to others. The appearance of virtue is often a penance, which people perform because they think it makes them fit to live in the world, not because it expresses their true natures. -

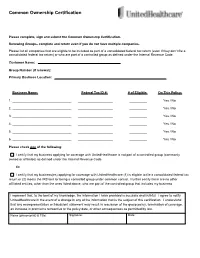

Common Ownership Form

Common Ownership Certification Please complete, sign and submit the Common Ownership Certification. Renewing Groups- complete and return even if you do not have multiple companies. Please list all companies that are eligible to be included as part of a consolidated federal tax return (even if they don’t file a consolidated federal tax return) or who are part of a controlled group as defined under the Internal Revenue Code. Customer Name: Group Number (if renewal): Primary Business Location: Business Name: Federal Tax ID #: # of Eligible: On This Policy: 1. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 2. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 3. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 4. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 5. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 6. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No Please check one of the following: I certify that my business applying for coverage with UnitedHealthcare is not part of a controlled group (commonly owned or affiliates) as defined under the Internal Revenue Code. Or I certify that my business(es) applying for coverage with UnitedHealthcare (1) is eligible to file a consolidated federal tax return or (2) meets the IRS test for being a controlled group under common control. I further certify there are no other affiliated entities, other than the ones listed above, who are part of the controlled group that includes my business. I represent that, to the best of my knowledge, the information I have provided is accurate and truthful. I agree to notify UnitedHealthcare in the event of a change in any of the information that is the subject of this certification. -

"A Critique of the “Common Ownership of the Earth” Thesis "

Article "A Critique of the “Common Ownership of the Earth” Thesis " Arash Abizadeh Les ateliers de l’éthique / The Ethics Forum, vol. 8, n° 2, 2013, p. 33-40. Pour citer cet article, utiliser l'information suivante : URI: http://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1021336ar DOI: 10.7202/1021336ar Note : les règles d'écriture des références bibliographiques peuvent varier selon les différents domaines du savoir. Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d'auteur. L'utilisation des services d'Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d'utilisation que vous pouvez consulter à l'URI http://www.erudit.org/apropos/utilisation.html Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l'Université de Montréal, l'Université Laval et l'Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. Érudit offre des services d'édition numérique de documents scientifiques depuis 1998. Pour communiquer avec les responsables d'Érudit : [email protected] Document téléchargé le 30 juin 2014 03:21 A CRITIQUE OF THE “COMMON OWNERSHIP OF THE EARTH” THESIS 1 ARASH ABIZADEH MCGILL UNIVERSITY 2 0 1 3 ABSTRACT In On Global Justice, Mathias Risse claims that the earth’s original resources are collecti- vely owned by all human beings in common, such that each individual has a moral right to use the original resources necessary for satisfying her basic needs. He also rejects the rival views that original resources are by nature owned by no one, owned by each human in equal shares, or owned and co-managed jointly by all humans. -

Ideologies of Autonomy

Wikipedia @ 20 Ideologies of Autonomy Christopher M. Cox Published on: Jun 11, 2019 Updated on: Jun 21, 2019 Wikipedia @ 20 Ideologies of Autonomy Introduction When I first began routinely using Wikipedia in the early 2000s, my interest owed as much to the model for online curation the site helped to popularize as it did Wikipedia itself. As a model for leveraging the potential of collective online intelligence, emerging modes of online productivity enabled everyday people to help build Wikipedia and, just as importantly for me, proliferated the use of “Wikis” to centralize and curate content ranging from organizational workflows to repositories for the intricacies of pop culture franchises. As a somewhat obsessive devotee of the television series Lost (2004-2011), I was especially enthusiastic about the latter, since the Lostpedia wiki was an essential part of my engagement with the series’ themes, mysteries, and motifs. On an almost daily basis during the show’s run, I found myself plunging ever deeper into Lostpedia, gleaming reminders of previous plot points and character interactions and using this knowledge to piece together ideas about the series’ sprawling mythology. Steadily, as Wikipedia also became a persistent fixture in my online media diet, I found myself using the site in a similar manner, often going down “Wikipedia holes” wherein I bounced from page to page, topic to topic, probing for knowledge of topics both familiar and obscure. This newfound ability to find, consume, and interact with a universe of ideas previously diffuse among various types of sources and institutions made me feel empowered to more readily self- direct my intellectual interests. -

Sovereignty of the Living Individual: Emerson and James on Politics and Religion

religions Article Sovereignty of the Living Individual: Emerson and James on Politics and Religion Stephen S. Bush Department of Religious Studies, Brown University, 59 George Street, Providence, RI 02912, USA; [email protected] Received: 20 July 2017; Accepted: 20 August 2017; Published: 25 August 2017 Abstract: William James and Ralph Waldo Emerson are both committed individualists. However, in what do their individualisms consist and to what degree do they resemble each other? This essay demonstrates that James’s individualism is strikingly similar to Emerson’s. By taking James’s own understanding of Emerson’s philosophy as a touchstone, I argue that both see individualism to consist principally in self-reliance, receptivity, and vocation. Putting these two figures’ understandings of individualism in comparison illuminates under-appreciated aspects of each figure, for example, the political implications of their individualism, the way that their religious individuality is politically engaged, and the importance of exemplarity to the politics and ethics of both of them. Keywords: Ralph Waldo Emerson; William James; transcendentalism; individualism; religious experience 1. Emersonian Individuality, According to James William James had Ralph Waldo Emerson in his bones.1 He consumed the words of the Concord sage, practically from birth. Emerson was a family friend who visited the infant James to bless him. James’s father read Emerson’s essays out loud to him and the rest of the family, and James himself worked carefully through Emerson’s corpus in the 1870’s and then again around 1903, when he gave a speech on Emerson (Carpenter 1939, p. 41; James 1982, p. 241). -

June 2017 Draft “A Theory of Cooperation with an Application To

June 2017 draft “A theory of cooperation with an application to market socialism” by John E. Roemer Yale University [email protected] 1 1. Man, the cooperative great ape It has become commonplace to observe that, among the five species of great ape, homo sapiens is by far the most cooperative. Fascinating experiments with infant humans and chimpanzees, by Michael Tomasello and others, give credence to the claim that a cooperative protocol is wired into to the human brain, and not to the chimpanzee brain. Tomasello’s work, summarized in two recent books with similar titles (2014, 2016), grounds the explanation of humans’ ability to cooperate with each other in their capacity to engage in joint intentionality, which is based upon a common knowledge of purpose and trust. There are fascinating evolutionary indications of early cooperative behavior among humans. I mention two: pointing and miming, and the sclera of the eye. Pointing and miming are pre-linguistic forms of communicating, probably having evolved due to their usefulness in cooperative pursuit of prey. If you and I were only competitors, I would have no interest in indicating the appearance of an animal that we, together, could catch and share. Similarly, the sclera (whites of the eyes) allow you to see what I am gazing it: if we cooperate in hunting, it is useful for me that you can see the animal I have spotted, for then we can trap it together and share it. Other great apes do not point and mime, nor do they possess sclera. Biologists have also argued that language would likely not have evolved in a non- cooperative species (Dunbar[2009] ). -

Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse

John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University Faculty Research Working Papers Series Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse Nov 2003 RWP03-044 The views expressed in the KSG Faculty Research Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or Harvard University. All works posted here are owned and copyrighted by the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism1 Mathias Risse John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University October 25, 2003 1. Left-libertarianism is not a new star on the sky of political philosophy, but it was through the recent publication of Peter Vallentyne and Hillel Steiner’s anthologies that it became clearly visible as a contemporary movement with distinct historical roots. “Left- libertarian theories of justice,” says Vallentyne, “hold that agents are full self-owners and that natural resources are owned in some egalitarian manner. Unlike most versions of egalitarianism, left-libertarianism endorses full self-ownership, and thus places specific limits on what others may do to one’s person without one’s permission. Unlike right- libertarianism, it holds that natural resources may be privately appropriated only with the permission of, or with a significant payment to, the members of society. Like right- libertarianism, left-libertarianism holds that the basic rights of individuals are ownership rights. Left-libertarianism is promising because it coherently underwrites both some demands of material equality and some limits on the permissible means of promoting this equality” (Vallentyne and Steiner (2000a), p 1; emphasis added). -

Libra Dissertation.Pdf

! ! ! ! ! On the Origin of Commons: Understanding Divergent State Preferences Over Property Rights in New Frontiers ! Catherine Shea Sanger ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy ! ! Department of Politics University of Virginia ! ! ! ! !1 of !195 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! “The first person who, having fenced off a plot of ground, took it into his head to say this is mine and found people simple enough to believe him, was the true founder of civil society.”1 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 1 Jean-Jacques Rousseau, "Discourse on the Origins and Foundations of Inequality among Men" in The First and Second Discourses, ed. Roger D. Masters, trans. Roger D. Masters and Judith Masters (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1964), p. 141 cited in Wendy Brown, Walled States, Waning Sovereignty (Cambridge, Mass.: Zone Books; Distributed by the MIT Press, 2010). 43. !2 of !195 Table of Contents ! Introduction: International Frontiers and Property Rights 5 Alternative Explanations for Variance in States’ Property Preferences 8 Methodology and Research Design 22 The First Frontier: Three Phases of High Seas Preference Formation 35 The Age of Discovery: Iberian Appropriation and Dutch-English Resistance, Late-15th – Early 17th Centuries 39 Making International Law: Anglo-Dutch Competition over the Status of European Seas, 17th Century 54 British Hegemony and Freedom of the Seas, 18th – 20th Centuries 63 Conclusion: What We’ve Learned from the Long