Mere Common Ownership and the Antitrust Laws

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Collective Ownership of the Earth Anna Stilz

BOOK SYMPOSIUM: ON GLOBAL JUSTICE On Collective Ownership of the Earth Anna Stilz n appealing and original aspect of Mathias Risse’s book On Global Justice is his argument for humanity’s collective ownership of the A earth. This argument focuses attention on states’ claims to govern ter- ritory, to control the resources of that territory, and to exclude outsiders. While these boundary claims are distinct from private ownership claims, they too are claims to control scarce goods. As such, they demand evaluation in terms of dis- tributive justice. Risse’s collective ownership approach encourages us to see the in- ternational system in terms of property relations, and to evaluate these relations according to a principle of distributive justice that could be justified to all humans as the earth’s collective owners. This is an exciting idea. Yet, as I argue below, more work needs to be done to develop plausible distribution principles on the basis of this approach. Humanity’s collective ownership of the earth is a complex notion. This is because the idea performs at least three different functions in Risse’s argument: first, as an abstract ideal of moral justification; second, as an original natural right; and third, as a continuing legitimacy constraint on property conventions. At the first level, collective ownership holds that all humans have symmetrical moral status when it comes to justifying principles for the distribution of earth’s original spaces and resources (that is, excluding what has been man-made). The basic thought is that whatever claims to control the earth are made, they must be compatible with the equal moral status of all human beings, since none of us created these resources, and no one specially deserves them. -

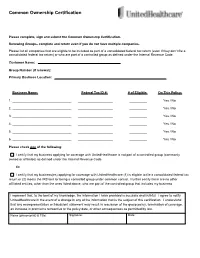

Common Ownership Form

Common Ownership Certification Please complete, sign and submit the Common Ownership Certification. Renewing Groups- complete and return even if you do not have multiple companies. Please list all companies that are eligible to be included as part of a consolidated federal tax return (even if they don’t file a consolidated federal tax return) or who are part of a controlled group as defined under the Internal Revenue Code. Customer Name: Group Number (if renewal): Primary Business Location: Business Name: Federal Tax ID #: # of Eligible: On This Policy: 1. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 2. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 3. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 4. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 5. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 6. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No Please check one of the following: I certify that my business applying for coverage with UnitedHealthcare is not part of a controlled group (commonly owned or affiliates) as defined under the Internal Revenue Code. Or I certify that my business(es) applying for coverage with UnitedHealthcare (1) is eligible to file a consolidated federal tax return or (2) meets the IRS test for being a controlled group under common control. I further certify there are no other affiliated entities, other than the ones listed above, who are part of the controlled group that includes my business. I represent that, to the best of my knowledge, the information I have provided is accurate and truthful. I agree to notify UnitedHealthcare in the event of a change in any of the information that is the subject of this certification. -

Will Sci-Hub Kill the Open Access Citation Advantage and (At Least for Now) Save Toll Access Journals?

Will Sci-Hub Kill the Open Access Citation Advantage and (at least for now) Save Toll Access Journals? David W. Lewis October 2016 © 2016 David W. Lewis. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license. Introduction It is a generally accepted fact that open access journal articles enjoy a citation advantage.1 This citation advantage results from the fact that open access journal articles are available to everyone in the word with an Internet collection. Thus, anyone with an interest in the work can find it and use it easily with no out-of-pocket cost. This use leads to citations. Articles in toll access journals on the other hand, are locked behind paywalls and are only available to those associated with institutions who can afford the subscription costs, or who are willing and able to purchase individual articles for $30 or more. There has always been some slippage in the toll access journal system because of informal sharing of articles. Authors will usually send copies of their work to those who ask and sometime post them on their websites even when this is not allowable under publisher’s agreements. Stevan Harnad and his colleagues proposed making this type of author sharing a standard semi-automated feature for closed articles in institutional repositories.2 The hashtag #ICanHazPDF can be used to broadcast a request for an article that an individual does not have access to.3 Increasingly, toll access articles are required by funder mandates to be made publically available, though usually after an embargo period. -

Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse

John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University Faculty Research Working Papers Series Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse Nov 2003 RWP03-044 The views expressed in the KSG Faculty Research Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or Harvard University. All works posted here are owned and copyrighted by the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism1 Mathias Risse John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University October 25, 2003 1. Left-libertarianism is not a new star on the sky of political philosophy, but it was through the recent publication of Peter Vallentyne and Hillel Steiner’s anthologies that it became clearly visible as a contemporary movement with distinct historical roots. “Left- libertarian theories of justice,” says Vallentyne, “hold that agents are full self-owners and that natural resources are owned in some egalitarian manner. Unlike most versions of egalitarianism, left-libertarianism endorses full self-ownership, and thus places specific limits on what others may do to one’s person without one’s permission. Unlike right- libertarianism, it holds that natural resources may be privately appropriated only with the permission of, or with a significant payment to, the members of society. Like right- libertarianism, left-libertarianism holds that the basic rights of individuals are ownership rights. Left-libertarianism is promising because it coherently underwrites both some demands of material equality and some limits on the permissible means of promoting this equality” (Vallentyne and Steiner (2000a), p 1; emphasis added). -

Libra Dissertation.Pdf

! ! ! ! ! On the Origin of Commons: Understanding Divergent State Preferences Over Property Rights in New Frontiers ! Catherine Shea Sanger ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy ! ! Department of Politics University of Virginia ! ! ! ! !1 of !195 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! “The first person who, having fenced off a plot of ground, took it into his head to say this is mine and found people simple enough to believe him, was the true founder of civil society.”1 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 1 Jean-Jacques Rousseau, "Discourse on the Origins and Foundations of Inequality among Men" in The First and Second Discourses, ed. Roger D. Masters, trans. Roger D. Masters and Judith Masters (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1964), p. 141 cited in Wendy Brown, Walled States, Waning Sovereignty (Cambridge, Mass.: Zone Books; Distributed by the MIT Press, 2010). 43. !2 of !195 Table of Contents ! Introduction: International Frontiers and Property Rights 5 Alternative Explanations for Variance in States’ Property Preferences 8 Methodology and Research Design 22 The First Frontier: Three Phases of High Seas Preference Formation 35 The Age of Discovery: Iberian Appropriation and Dutch-English Resistance, Late-15th – Early 17th Centuries 39 Making International Law: Anglo-Dutch Competition over the Status of European Seas, 17th Century 54 British Hegemony and Freedom of the Seas, 18th – 20th Centuries 63 Conclusion: What We’ve Learned from the Long -

Piracy of Scientific Papers in Latin America: an Analysis of Sci-Hub Usage Data

Developing Latin America Piracy of scientific papers in Latin America: An analysis of Sci-Hub usage data Juan D. Machin-Mastromatteo Alejandro Uribe-Tirado Maria E. Romero-Ortiz This article was originally published as: Machin-Mastromatteo, J.D., Uribe-Tirado, A., and Romero-Ortiz, M. E. (2016). Piracy of scientific papers in Latin America: An analysis of Sci-Hub usage data. Information Development, 32(5), 1806–1814. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0266666916671080 Abstract Sci-Hub hosts pirated copies of 51 million scientific papers from commercial publishers. This article presents the site’s characteristics, it criticizes that it might be perceived as a de-facto component of the Open Access movement, it replicates an analysis published in Science using its available usage data, but limiting it to Latin America, and presents implications caused by this site for information professionals, universities and libraries. Keywords: Sci-Hub, piracy, open access, scientific articles, academic databases, serials crisis Scientific articles are vital for students, professors and researchers in universities, research centers and other knowledge institutions worldwide. When academic publishing started, academies, institutions and professional associations gathered articles, assessed their quality, collected them in journals, printed and distributed its copies; with the added difficulty of not having digital technologies. Producing journals became unsustainable for some professional societies, so commercial scientific publishers started appearing and assumed printing, sales and distribution on their behalf, while academics retained the intellectual tasks. Elsevier, among the first publishers, emerged to cover operations costs and profit from sales, now it is part of an industry that grew from the process of scientific communication; a 10 billion US dollar business (Murphy, 2016). -

Practical Anonymous Networking?

gap – practical anonymous networking? Krista Bennett Christian Grothoff S3 lab and CERIAS, Department of Computer Sciences, Purdue University [email protected], [email protected] http://www.gnu.org/software/GNUnet/ Abstract. This paper describes how anonymity is achieved in gnunet, a framework for anonymous distributed and secure networking. The main focus of this work is gap, a simple protocol for anonymous transfer of data which can achieve better anonymity guarantees than many traditional indirection schemes and is additionally more efficient. gap is based on a new perspective on how to achieve anonymity. Based on this new perspective it is possible to relax the requirements stated in traditional indirection schemes, allowing individual nodes to balance anonymity with efficiency according to their specific needs. 1 Introduction In this paper, we present the anonymity aspect of gnunet, a framework for secure peer-to-peer networking. The gnunet framework provides peer discovery, link encryption and message-batching. At present, gnunet’s primary application is anonymous file-sharing. The anonymous file-sharing application uses a content encoding scheme that breaks files into 1k blocks as described in [1]. The 1k blocks are transmitted using gnunet’s anonymity protocol, gap. This paper describes gap and how it attempts to achieve privacy and scalability in an environment with malicious peers and actively participating adversaries. The gnunet core API offers node discovery, authentication and encryption services. All communication between nodes in the network is confidential; no host outside the network can observe the actual contents of the data that flows through the network. Even the type of the data cannot be observed, as all packets are padded to have identical size. -

Self-Ownership, Social Justice and World-Ownership Fabien Tarrit

Self-Ownership, Social Justice and World-Ownership Fabien Tarrit To cite this version: Fabien Tarrit. Self-Ownership, Social Justice and World-Ownership. Buletinul Stiintific Academia de Studii Economice di Bucuresti, Editura A.S.E, 2008, 9 (1), pp.347-355. hal-02021060 HAL Id: hal-02021060 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02021060 Submitted on 15 Feb 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Self-Ownership, Social Justice and World-Ownership TARRIT Fabien Lecturer in Economics OMI-LAME Université de Reims Champagne-Ardenne France Abstract: This article intends to demonstrate that the concept of self-ownership does not necessarily imply a justification of inequalities of condition and a vindication of capitalism, which is traditionally the case. We present the reasons of such an association, and then we specify that the concept of self-ownership as a tool in political philosophy can be used for condemning the capitalist exploitation. Keywords: Self-ownership, libertarianism, capitalism, exploitation JEL : A13, B49, B51 2 The issue of individual freedom as a stake went through the philosophical debate since the Greek antiquity. We deal with that issue through the concept of self-ownership. -

Resource-Sharing Computer Communications Networks

PROCEEDISGS OF THE IEEE, VOL. 60, NO. 11, NOVEMBER 1972 1397 ington. D. C.: Spartan, 1970, pp. 569-579. [47] L. G. Roberts and B. Wessler, “The ARP.4 computer network de- [34] D. Klejtman,“Methods of investigatingconnectivity of large velopmentto achieve resource sharing, in Spring Joint Compztfer graphs, IEEE Trans.Circuit Theory (Corresp.),vol. CT-16, pp. Conf., AFIPS Conf. Proc., 1970, pp. 543-519. 232-233, May 1969. [48] --, “The ARPA computer network,” in Computer Communication [35] P. Krolak, IV. Felts,and G. Marble,“A man-machine approach Networks, F. Kuo and X. .‘\bramson, Eds.Iiew York: Prentice- towardsolving the traveling salesman problem,’! Commun.Ass. Hall, 1973, to be published. Comput. Mach., vol. 14, pp. 327-335, May 1971. [49] B. Rothfarb and M. Goldstein, ‘The one terminal Telpak problem,” [36] S. Lin,“Computer solutions of thetraveling salesman problem,” Oper. Res., vol. 19, pp. 156-169, Jan.-Feb. 1971. Bell Sysf. Tech. J., vol. 44, pp. 2245-2269, 1965. [SO] R. L. Sharma and M.T. El Bardai, “Suboptimal communications [37] T. Marilland L. G. Roberts, “Toward a cooperative netwotk of network synthesis,” in Proc. Int. Conf. Communications, vol. 7, pp. time-shared computers,” in Fall Joint Computer Conf.?AFIPS Conf. 19-11-19-16, 1970. Proc. Washington, D.C.: Spartan, 1966. ..[Sl] K. Steiglitz, P. Weiner, and D.J. Kleitman, “The design of minimum [38] B. Meister,H. R. Muller, and H. R.Rudin, “Sew optimization cost survivable networks,’! IEEE Trans. Circuit Theory, vol. CT-16, criteriafor message-switching networks,’ IEEE Trans.Commun. pp. 455-260, Nov. -

Common Ownership Community “COC”

So, are you a good neighbor? Do you know your association’s Board of Directors? Do you … ? Are you aware of when and where your association • Pay your assessments on time? meets? Have you reviewed your association’s • Abide by the rules, regulations and bylaws? bylaws? • Attend Board of Directors meetings? • Vote in elections and on critical matters? How to be a Consider getting involved. Get engaged and be aware! For additional information on Common GOOD NEIGHBOR in a Ownership Communities, please contact the • Browse your Association’s newsletter and email following: blasts, so that you have an idea of what’s going on and, so that you’ll be able to participate Office of Community Relations Common if there’s something you strongly agree or Ownership Communities disagree with. Phone: 301-952-4729 http://www.princegeorgescountymd.gov/921/ • Attend Association meetings. This will help Common-Ownership-Communities you find out what’s going on in your community and will help you become informed. You’ll FHA Resource Center have a greater influence over what happens https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/housing/ in your building or neighborhood and it’s an sfh/fharesourcectr opportunity to meet your neighbors. Office of the Attorney General Consumer At the end of the day, there is a difference between Protection Division living in a community and being a part of that Phone: 877-261-8807 particular community. While being part of an http://www.marylandattorneygeneral.gov/ Common Association can be a bit of extra work, it’s worth CPD%20Documents/Tips-Publications/ putting some effort into being a good member. -

Downloaded from Elgar Online at 09/26/2021 10:10:51PM Via Free Access

JOBNAME: EE3 Hodgson PAGE: 2 SESS: 3 OUTPUT: Thu Jun 27 12:00:07 2019 1. What does socialism mean? Under capitalism, man exploits his fellow man. Under socialism it is precisely the opposite. Eastern European joke from the Communist era1 The word socialism is modern, but the impulse behind it is ancient. The idea of holding property in common goes back to Ancient Greece and is found in the Bible.2 It has been harboured by some religions and it has been the call of radicals for centuries. In his 1516 book Utopia, Sir Thomas More imagined a system where everything was held in common ownership and internal trade was abolished. Unlike most other proposals for common ownership before the 1840s, More’s Utopia envisioned cities of between 60 000 and 100 000 adults. It is the first known proposal for what I call big socialism. Before the rise of Marxism, the predominant vision of common ownership was small-scale, rural and agricultural. It was often motivated by religious doctrine. In Germany in the 1520s the radical Protestant Thomas Müntzer proposed a Christian communism. From 1649 to 1650, during the English Civil War, the Diggers set up religious communes whose members worked together on the soil and shared its produce. There are other examples of socialism before the word was coined.3 This chapter is about the origins, meaning and evolution of the words socialism and communism. They are virtual synonyms, both largely referring to common ownership of the means of production and to the abolition of private property. -

Measuring Freenet in the Wild: Censorship-Resilience Under Observation

Measuring Freenet in the Wild: Censorship-resilience under Observation Stefanie Roosy, Benjamin Schillerz, Stefan Hackerz, Thorsten Strufey yTechnische Universität Dresden, <firstname.lastname>@tu-dresden.de zTechnische Universität Darmstadt, <lastname>@cs.tu-darmstadt.de Abstract. Freenet, a fully decentralized publication system designed for censorship-resistant communication, exhibits long delays and low success rates for finding and retrieving content. In order to improve its perfor- mance, an in-depth understanding of the deployed system is required. Therefore, we performed an extensive measurement study accompanied by a code analysis to identify bottlenecks of the existing algorithms and obtained a realistic user model for the improvement and evaluation of new algorithms. Our results show that 1) the current topology control mechanisms are suboptimal for routing and 2) Freenet is used by several tens of thousands of users who exhibit uncharacteristically long online times in comparison to other P2P systems. 1 Introduction Systems that allow users to communicate anonymously, and to publish data without fear of retribution, have become ever more popular in the light of re- cent events1. Freenet [1–3] is a widely deployed completely decentralized system focusing on anonymity and censorship-resilience. In its basic version, the Open- net mode, it provides sender and receiver anonymity but establishes connections between the devices of untrusted users. In the Darknet mode, nodes only con- nect to nodes of trusted parties. Freenet aims to achieve fast message delivery over short routes by arranging nodes in routable small-world network. However, Freenet’s performance has been found to be insufficient, exhibiting long delays and frequent routing failures [4].