Intellectual Property, Globalization, and Left-Libertarianism*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Collective Ownership of the Earth Anna Stilz

BOOK SYMPOSIUM: ON GLOBAL JUSTICE On Collective Ownership of the Earth Anna Stilz n appealing and original aspect of Mathias Risse’s book On Global Justice is his argument for humanity’s collective ownership of the A earth. This argument focuses attention on states’ claims to govern ter- ritory, to control the resources of that territory, and to exclude outsiders. While these boundary claims are distinct from private ownership claims, they too are claims to control scarce goods. As such, they demand evaluation in terms of dis- tributive justice. Risse’s collective ownership approach encourages us to see the in- ternational system in terms of property relations, and to evaluate these relations according to a principle of distributive justice that could be justified to all humans as the earth’s collective owners. This is an exciting idea. Yet, as I argue below, more work needs to be done to develop plausible distribution principles on the basis of this approach. Humanity’s collective ownership of the earth is a complex notion. This is because the idea performs at least three different functions in Risse’s argument: first, as an abstract ideal of moral justification; second, as an original natural right; and third, as a continuing legitimacy constraint on property conventions. At the first level, collective ownership holds that all humans have symmetrical moral status when it comes to justifying principles for the distribution of earth’s original spaces and resources (that is, excluding what has been man-made). The basic thought is that whatever claims to control the earth are made, they must be compatible with the equal moral status of all human beings, since none of us created these resources, and no one specially deserves them. -

Libertarianism, Culture, and Personal Predispositions

Undergraduate Journal of Psychology 22 Libertarianism, Culture, and Personal Predispositions Ida Hepsø, Scarlet Hernandez, Shir Offsey, & Katherine White Kennesaw State University Abstract The United States has exhibited two potentially connected trends – increasing individualism and increasing interest in libertarian ideology. Previous research on libertarian ideology found higher levels of individualism among libertarians, and cross-cultural research has tied greater individualism to making dispositional attributions and lower altruistic tendencies. Given this, we expected to observe positive correlations between the following variables in the present research: individualism and endorsement of libertarianism, individualism and dispositional attributions, and endorsement of libertarianism and dispositional attributions. We also expected to observe negative correlations between libertarianism and altruism, dispositional attributions and altruism, and individualism and altruism. Survey results from 252 participants confirmed a positive correlation between individualism and libertarianism, a marginally significant positive correlation between libertarianism and dispositional attributions, and a negative correlation between individualism and altruism. These results confirm the connection between libertarianism and individualism observed in previous research and present several intriguing questions for future research on libertarian ideology. Key Words: Libertarianism, individualism, altruism, attributions individualistic, made apparent -

Up from Individualism (The Brennan Center Symposium On

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Articles Faculty Scholarship 1998 Up from Individualism (The rB ennan Center Symposium on Constitutional Law)." Donald J. Herzog University of Michigan Law School, [email protected] Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles/141 Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles Part of the Jurisprudence Commons, Law and Society Commons, and the Public Law and Legal Theory Commons Recommended Citation Herzog, Donald J. "Up from Individualism (The rB ennan Center Symposium on Constitutional Law)." Cal. L. Rev. 86, no. 3 (1998): 459-67. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Up from Individualism Don Herzogt I was sitting, ruefully contemplating the dilemmas of being a com- mentator, wondering whether I had the effrontery to rise and offer a dreadful confession: the first time I encountered the counter- majoritarian difficulty, I didn't bite. I didn't say, "Wow, that's a giant problem." I didn't immediately start casting about for ingenious ways to solve or dissolve it. I just shrugged. Now I don't think that's because my commitments to either democracy or constitutionalism are somehow faulty or suspect. Nor do I think it's that they obviously cohere. It's rather that the framing, "look, these nine unelected characters can strike down a statute passed in procedurally valid ways by a democratically elected legislature," struck me as unhelpful. -

Conceptual Framework Spring, 2014

Conceptual Framework Spring, 2014 Conceptual Framework University of Arkansas at Monticello School of Education 1 Conceptual Framework Spring, 2014 UNIVERSITY OF ARKANSAS AT MONTICELLO (UAM) SCHOOL OF EDUCATION THE CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK Introduction The University of Arkansas at Monticello (UAM) has a rich educational heritage of teaching and learning that has provided a “Century of Opportunity” for the residents of southeast Arkansas and the state since its humble beginnings as The Fourth District Agricultural School in 1909. To understand the history of teacher education at UAM, the beginnings of the university itself must be explored. Classes began in 1911 with students in the sixth through twelfth grades attending. Freshman and sophomore college courses were added in 1923 and the institution was accredited as a junior college in 1928. Senior college courses were added in 1933 and, the following year, the first degrees were granted by Arkansas A&M College. The campus was established on what was once part of a 6,000 acre cotton plantation owned by Judge and Mrs. William Turner Wells. “Judge Billy” and “Miss Pattie” were prominent figures in southeast Arkansas and the name of Wells is imbedded in the social and political history of the state. Judge and Mrs. Wells lived the idyllic life of Southern planters and entertained frequently in their plantation home that was located on what is now the site of the Fred J. Taylor Library. In April of 1909, the Arkansas General Assembly passed Act 100 which created four district agricultural schools. For the southeast district, descendants of Judge and Mrs. Wells offered the Wells Plantation home site with 200 acres of contiguous land for the new school/experiment farm. -

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK Christian Brothers University

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK Christian Brothers University Christian Brothers University Education Unit Conceptual Framework The conceptual framework of the education unit has been influenced by the mission and core values of the university and the mission statement of the School of Arts. The university’s mission statement is: Educating minds. Touching hearts. Remembering the presence of God. We believe that this mission statement is best represented by the core values of the university. The core values are: Faith: Our belief in God permeates every facet of the University's life. Service: We reach out to serve one another and those beyond our campus. Community: We work to build better communities and a better society. The mission statement for the School of Arts was rewritten in 2013 and states: To advance the Lasallian synthesis of knowledge and service by teaching students to think, to communicate, to evaluate, and to appreciate. Building on the core values and the mission statement are the Department of Education’s candidate proficiencies as identified in the conceptual framework. This conceptual framework includes four themes – Servant- Leader, Effective and Reflective Practitioner, Champion of Individual Learner Potential, and Builder of Vibrant Learning Communities. These themes are outlined below: Theme/Core Concept: Servant-Leader 1. Candidates exhibit moral and ethical responsibility, skills of leadership, service and professionalism that represent concern for the welfare of others above self-concern and self- interest. 2. Candidates express commitment to the human mission of education and to the goals of access, equity, and opportunity. 3. Candidates show respect for others by honoring the worth and dignity of children, families, community, and colleagues. -

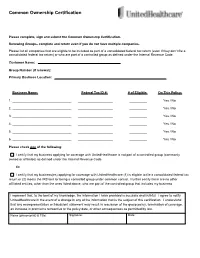

Common Ownership Form

Common Ownership Certification Please complete, sign and submit the Common Ownership Certification. Renewing Groups- complete and return even if you do not have multiple companies. Please list all companies that are eligible to be included as part of a consolidated federal tax return (even if they don’t file a consolidated federal tax return) or who are part of a controlled group as defined under the Internal Revenue Code. Customer Name: Group Number (if renewal): Primary Business Location: Business Name: Federal Tax ID #: # of Eligible: On This Policy: 1. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 2. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 3. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 4. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 5. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 6. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No Please check one of the following: I certify that my business applying for coverage with UnitedHealthcare is not part of a controlled group (commonly owned or affiliates) as defined under the Internal Revenue Code. Or I certify that my business(es) applying for coverage with UnitedHealthcare (1) is eligible to file a consolidated federal tax return or (2) meets the IRS test for being a controlled group under common control. I further certify there are no other affiliated entities, other than the ones listed above, who are part of the controlled group that includes my business. I represent that, to the best of my knowledge, the information I have provided is accurate and truthful. I agree to notify UnitedHealthcare in the event of a change in any of the information that is the subject of this certification. -

The Philosophy of Free Trade and Its Applicability in East Asia

ENCUENTROS ISSN 1692-5858. No. 1. Junio de 2011 • P. 69-82 Is Free Trade a Culture-Bound Ideal? The Philosophy of Free Trade and Its Applicability in East Asia ¿Está ligada la cultura al pensamiento de libre comercio?: su filosofía y aplicabilidad en el Este de Asia Tae Jin Park [email protected] West Virgina State University ABSTRACT Proponents of free trade, especially theorists known as “neo-liberals,” preach free trade as a global ethic and emphasize four great benefits from it: 1) reciprocal economic growth; 2) individual freedom; 3) political democracy; 4) international peace. This review article will examine the validity of these assumptions in East Asia. Although many East Asian states are great beneficiaries of the liberal international trade system that has developed since the end of World War II, their political and economic developments generally do not conform to Western expectations because their cultural values are still “Confucian” and their political economy relied heavily on state leadership. The philosophy of free trade is largely incompatible with East Asian historical experiences. The credibility of the free trade doctrine in East Asia comes from the power and influence of the U.S. rather than from the usefulness of the free trade doctrine. Key words: Free trade, neo-liberalism, East Asia, Confucianism, capitalism, democracy. RESUMEN Los defensores del libre comercio, especialmente los teóricos se conocen como “neo-liberales,” predicar el libre comercio como una ética global y hacer hincapié en cuatro grandes beneficios: 1) crecimiento económico recíproco, 2) la libertad individual, 3) la democracia política, y 4) la paz internacional. -

U.S. POLICY in the AMERICAS and the ROLE of FREE TRADE by Otto J

❏ U.S. POLICY IN THE AMERICAS AND THE ROLE OF FREE TRADE By Otto J. Reich, Assistant Secretary, Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs, U.S. Department of State Freer trade has long been a centerpiece of U.S. policy in the The United States knows that our destiny is tied to the Americas, not only to boost economic growth but also to well-being of our neighbors. We understand that we strengthen the ties that unite the region's 34 democracies, says cannot be safe at home if our neighborhood is not safe. Otto Reich, the United States' top diplomat for the region. We appreciate that our prosperity grows as our neighbors “There is a fundamental and mutually supporting dynamic prosper. We believe that healthy relations between the between political and economic freedom,” he says. Having United States and the other countries of the Western recently obtained a grant of trade promotion authority (TPA) Hemisphere are to our mutual benefit, and this from Congress, Bush Administration officials are poised to perspective informs our policy toward the region. pursue the FTAA talks with renewed vigor as the United States and Brazil prepare to assume joint leadership for the While we in the United States believe that trade is the final phase of the negotiations. Ambassador Reich most beneficial element of our economic relationship acknowledges legitimate concerns — in developed and with the world, we are increasing our foreign aid and its developing countries alike — over the potential disruptions efficacy. For 2002, the U.S. Agency for International of open trade, but says “without change, there is only Development (USAID) foreign aid program for Latin stagnation.” America and the Caribbean amounted to $828 million. -

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

Frontier Culture: the Roots and Persistence of “Rugged Individualism” in the United States Samuel Bazzi, Martin Fiszbein, and Mesay Gebresilasse NBER Working Paper No

Frontier Culture: The Roots and Persistence of “Rugged Individualism” in the United States Samuel Bazzi, Martin Fiszbein, and Mesay Gebresilasse NBER Working Paper No. 23997 November 2017, Revised August 2020 JEL No. D72,H2,N31,N91,P16 ABSTRACT The presence of a westward-moving frontier of settlement shaped early U.S. history. In 1893, the historian Frederick Jackson Turner famously argued that the American frontier fostered individualism. We investigate the Frontier Thesis and identify its long-run implications for culture and politics. We track the frontier throughout the 1790–1890 period and construct a novel, county-level measure of total frontier experience (TFE). Historically, frontier locations had distinctive demographics and greater individualism. Long after the closing of the frontier, counties with greater TFE exhibit more pervasive individualism and opposition to redistribution. This pattern cuts across known divides in the U.S., including urban–rural and north–south. We provide evidence on the roots of frontier culture, identifying both selective migration and a causal effect of frontier exposure on individualism. Overall, our findings shed new light on the frontier’s persistent legacy of rugged individualism. Samuel Bazzi Mesay Gebresilasse Department of Economics Amherst College Boston University 301 Converse Hall 270 Bay State Road Amherst, MA 01002 Boston, MA 02215 [email protected] and CEPR and also NBER [email protected] Martin Fiszbein Department of Economics Boston University 270 Bay State Road Boston, MA 02215 and NBER [email protected] Frontier Culture: The Roots and Persistence of “Rugged Individualism” in the United States∗ Samuel Bazziy Martin Fiszbeinz Mesay Gebresilassex Boston University Boston University Amherst College NBER and CEPR and NBER July 2020 Abstract The presence of a westward-moving frontier of settlement shaped early U.S. -

Libertarianism Karl Widerquist, Georgetown University-Qatar

Georgetown University From the SelectedWorks of Karl Widerquist 2008 Libertarianism Karl Widerquist, Georgetown University-Qatar Available at: https://works.bepress.com/widerquist/8/ Libertarianism distinct ideologies using the same label. Yet, they have a few commonalities. [233] [V1b-Edit] [Karl Widerquist] [] [w6728] Libertarian socialism: Libertarian socialists The word “libertarian” in the sense of the believe that all authority (government or combination of the word “liberty” and the private, dictatorial or democratic) is suffix “-ian” literally means “of or about inherently dangerous and possibly tyrannical. freedom.” It is an antonym of “authoritarian,” Some endorse the motto: where there is and the simplest dictionary definition is one authority, there is no freedom. who advocates liberty (Simpson and Weiner Libertarian socialism is also known as 1989). But the name “libertarianism” has “anarchism,” “libertarian communism,” and been adopted by several very different “anarchist communism,” It has a variety of political movements. Property rights offshoots including “anarcho-syndicalism,” advocates have popularized the association of which stresses worker control of enterprises the term with their ideology in the United and was very influential in Latin American States and to a lesser extent in other English- and in Spain in the 1930s (Rocker 1989 speaking countries. But they only began [1938]; Woodcock 1962); “feminist using the term in 1955 (Russell 1955). Before anarchism,” which stresses person freedoms that, and in most of the rest of the world (Brown 1993); and “eco-anarchism” today, the term has been associated almost (Bookchin 1997), which stresses community exclusively with leftists groups advocating control of the local economy and gives egalitarian property rights or even the libertarian socialism connection with Green abolition of private property, such as and environmental movements. -

Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse

John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University Faculty Research Working Papers Series Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse Nov 2003 RWP03-044 The views expressed in the KSG Faculty Research Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or Harvard University. All works posted here are owned and copyrighted by the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism1 Mathias Risse John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University October 25, 2003 1. Left-libertarianism is not a new star on the sky of political philosophy, but it was through the recent publication of Peter Vallentyne and Hillel Steiner’s anthologies that it became clearly visible as a contemporary movement with distinct historical roots. “Left- libertarian theories of justice,” says Vallentyne, “hold that agents are full self-owners and that natural resources are owned in some egalitarian manner. Unlike most versions of egalitarianism, left-libertarianism endorses full self-ownership, and thus places specific limits on what others may do to one’s person without one’s permission. Unlike right- libertarianism, it holds that natural resources may be privately appropriated only with the permission of, or with a significant payment to, the members of society. Like right- libertarianism, left-libertarianism holds that the basic rights of individuals are ownership rights. Left-libertarianism is promising because it coherently underwrites both some demands of material equality and some limits on the permissible means of promoting this equality” (Vallentyne and Steiner (2000a), p 1; emphasis added).