Capitalism, Socialism and Utopia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A New Politics of the Commons

Published in Renewal magazine, December 17, 2007. Renewal is a Labour-oriented political journal dedicated to social democracy” published in London. A New Politics of the Commons By David Bollier One of the most stubborn problems in confronting the pathologies of the neoliberal political order is the limitations of our language. We do not have an adequate public vocabulary to describe the plunder of globalized markets. We have trouble highlighting the social inequities that are built into conventional economics and political discourse. We do not have a grand narrative with compelling sub-plots to set forth an alternative vision, one that can both stir the blood and show intellectual sophistication. That’s the bad news. The good news is that there is a brave, decentralized movement on the march that is addressing these problems with ingenuity and patience. The focus of this movement is the commons. The commons is still an embryonic vision. It will require time to evolve. But it is a vision with great potential, perhaps because it is not being advanced by an intellectual elite or a political party, but by a hardy band of resourceful irregulars on the periphery of conventional politics. (That’s always where the most interesting new things originate.) These commoners are now starting to find each other, a convergence that augurs great things. To be a bit more concrete: This proto-commons movement consists of environmentalists trying to protect wilderness areas and win fair compensation for the corporate use of public lands. It includes local communities trying to prevent multinational water companies from privatizing public water works and converting groundwater into over- priced, branded bottles of water. -

On Collective Ownership of the Earth Anna Stilz

BOOK SYMPOSIUM: ON GLOBAL JUSTICE On Collective Ownership of the Earth Anna Stilz n appealing and original aspect of Mathias Risse’s book On Global Justice is his argument for humanity’s collective ownership of the A earth. This argument focuses attention on states’ claims to govern ter- ritory, to control the resources of that territory, and to exclude outsiders. While these boundary claims are distinct from private ownership claims, they too are claims to control scarce goods. As such, they demand evaluation in terms of dis- tributive justice. Risse’s collective ownership approach encourages us to see the in- ternational system in terms of property relations, and to evaluate these relations according to a principle of distributive justice that could be justified to all humans as the earth’s collective owners. This is an exciting idea. Yet, as I argue below, more work needs to be done to develop plausible distribution principles on the basis of this approach. Humanity’s collective ownership of the earth is a complex notion. This is because the idea performs at least three different functions in Risse’s argument: first, as an abstract ideal of moral justification; second, as an original natural right; and third, as a continuing legitimacy constraint on property conventions. At the first level, collective ownership holds that all humans have symmetrical moral status when it comes to justifying principles for the distribution of earth’s original spaces and resources (that is, excluding what has been man-made). The basic thought is that whatever claims to control the earth are made, they must be compatible with the equal moral status of all human beings, since none of us created these resources, and no one specially deserves them. -

The Politics of Indian Property Rights

Property rights, selective enforcement, and the destruction of wealth on Indian lands Ilia Murtazashvili* University of Pittsburgh Abstract This paper reconceptualizes the nature of property institutions in the United States. Conventional economic analysis suggests that the U.S. established private property rights protection as a public good by the end of the nineteenth century. The experience of Indians suggests otherwise. During the mid-nineteenth century, the economic fortunes of settlers on public lands owned by the United States government and Indians diverged. Settlers secured legal property rights and self-governance, while members of Indian nations were forced into an inequitable property system in which the federal government established an institutionalized system to discriminate against reservation Indians. The property system is most appropriately described as a selective enforcement regime in which some groups enjoy credible and effective property rights at the expense of others who confront a predatory state and institutionalized property insecurity. The persistence of the selective enforcement regime explains the persistence of poverty among reservation Indians. * Email: [email protected]. Paper prepared for the Searle Workshop on “Indigenous Capital, Growth, and Property Rights: The Legacy of Colonialism,” Hoover Institution, Stanford University. Many thanks to Terry Anderson and Nick Parker for organizing the workshop. 1 2 Introduction The United States is often used as an example to illustrate the beneficial consequences of private property rights for economic growth and development. Sokoloff and Engerman (2000) use differences in land policy to explain the reversal of economic fortunes of the U.S. and Spanish America, which started with a similar per capita GDP around 1800 but diverged substantially by the twentieth century. -

Chapter 4 Freedom and Progress

Chapter 4 Freedom and Progress The best road to progress is freedom’s road. John F. Kennedy The only freedom which deserves the name, is that of pursuing our own good in our own way, so long as we do not attempt to deprive others of theirs, or impeded their efforts to obtain it. John Stuart Mill To cull the inestimable benefits assured by freedom of the press, it is necessary to put up with the inevitable evils springing therefrom. Alexis de Tocqueville Freedom is necessary to generate progress; people also value freedom as an important component of progress. This chapter will contend that both propositions are correct. Without liberty, there will be little or no progress; most people will consider an expansion in freedom as progress. Neither proposition would win universal acceptance. Some would argue that a totalitarian state can marshal the resources to generate economic growth. Many will contend that too much liberty induces libertine behavior and is destructive of society, peace, and the family. For better or worse, the record shows that freedom has increased throughout the world over the last few centuries and especially over the last few decades. There are of course many examples of non-free, totalitarian, ruthless government on the globe, but their number has decreased and now represents a smaller proportion of the world’s population. Perhaps this growth of freedom is partially responsible for the breakdown of the family and the rise in crime, described in the previous chapter. Dictators do tolerate less crime and are often very repressive of deviant sexual behavior, but, as the previous chapter reported, divorce and illegitimacy are more connected with improved income of women than with a permissive society. -

A Critique of John Stuart Mill Chris Daly

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Honors Theses University Honors Program 5-2002 The Boundaries of Liberalism in a Global Era: A Critique of John Stuart Mill Chris Daly Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/uhp_theses Recommended Citation Daly, Chris, "The Boundaries of Liberalism in a Global Era: A Critique of John Stuart Mill" (2002). Honors Theses. Paper 131. This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the University Honors Program at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. r The Boundaries of Liberalism in a Global Era: A Critique of John Stuart Mill Chris Daly May 8, 2002 r ABSTRACT The following study exanunes three works of John Stuart Mill, On Liberty, Utilitarianism, and Three Essays on Religion, and their subsequent effects on liberalism. Comparing the notion on individual freedom espoused in On Liberty to the notion of the social welfare in Utilitarianism, this analysis posits that it is impossible for a political philosophy to have two ultimate ends. Thus, Mill's liberalism is inherently flawed. As this philosophy was the foundation of Mill's progressive vision for humanity that he discusses in his Three Essays on Religion, this vision becomes paradoxical as well. Contending that the neo-liberalist global economic order is the contemporary parallel for Mill's religion of humanity, this work further demonstrates how these philosophical flaws have spread to infect the core of globalization in the 21 st century as well as their implications for future international relations. -

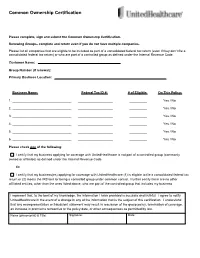

Common Ownership Form

Common Ownership Certification Please complete, sign and submit the Common Ownership Certification. Renewing Groups- complete and return even if you do not have multiple companies. Please list all companies that are eligible to be included as part of a consolidated federal tax return (even if they don’t file a consolidated federal tax return) or who are part of a controlled group as defined under the Internal Revenue Code. Customer Name: Group Number (if renewal): Primary Business Location: Business Name: Federal Tax ID #: # of Eligible: On This Policy: 1. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 2. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 3. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 4. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 5. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 6. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No Please check one of the following: I certify that my business applying for coverage with UnitedHealthcare is not part of a controlled group (commonly owned or affiliates) as defined under the Internal Revenue Code. Or I certify that my business(es) applying for coverage with UnitedHealthcare (1) is eligible to file a consolidated federal tax return or (2) meets the IRS test for being a controlled group under common control. I further certify there are no other affiliated entities, other than the ones listed above, who are part of the controlled group that includes my business. I represent that, to the best of my knowledge, the information I have provided is accurate and truthful. I agree to notify UnitedHealthcare in the event of a change in any of the information that is the subject of this certification. -

John Stuart Mill's Evaluations of Poetry

JOHN STUART MILL'S EVALUATIONS OF POETRY AND THEIR INFLUENCE UPON HIS INTELLECTUAL DEVELOPMENT by MILLO RUNDLE THOMPSON SHAW B.A., University of British Columbia, 1949 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of English We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1971 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of ENGLISH The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada Date October 1970 i JOHN STUART MILL'S EVALUATIONS OF POETRY AND THEIR INFLUENCE UPON HIS INTELLECTUAL DEVELOPMENT ABSTRACT The education of John Stuart Mill was one of the most unusual ever planned or experienced. Beginning with his learning Greek at the age of three and con• tinuing without a break of any kind to the age of four• teen, it constituted an almost total control of Mill's every waking activity, with the important exception of his visit to France at fourteen, until his appoint• ment to the East India Company in 1823. It emphasized the "tabula rasa" theory, the effect of external cir• cumstances on the developing mind, Hartley's Associa- tionist theory, and the judicious use of the Utilitarian theories of the "pleasure-pain" principle. -

Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse

John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University Faculty Research Working Papers Series Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse Nov 2003 RWP03-044 The views expressed in the KSG Faculty Research Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or Harvard University. All works posted here are owned and copyrighted by the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism1 Mathias Risse John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University October 25, 2003 1. Left-libertarianism is not a new star on the sky of political philosophy, but it was through the recent publication of Peter Vallentyne and Hillel Steiner’s anthologies that it became clearly visible as a contemporary movement with distinct historical roots. “Left- libertarian theories of justice,” says Vallentyne, “hold that agents are full self-owners and that natural resources are owned in some egalitarian manner. Unlike most versions of egalitarianism, left-libertarianism endorses full self-ownership, and thus places specific limits on what others may do to one’s person without one’s permission. Unlike right- libertarianism, it holds that natural resources may be privately appropriated only with the permission of, or with a significant payment to, the members of society. Like right- libertarianism, left-libertarianism holds that the basic rights of individuals are ownership rights. Left-libertarianism is promising because it coherently underwrites both some demands of material equality and some limits on the permissible means of promoting this equality” (Vallentyne and Steiner (2000a), p 1; emphasis added). -

Libra Dissertation.Pdf

! ! ! ! ! On the Origin of Commons: Understanding Divergent State Preferences Over Property Rights in New Frontiers ! Catherine Shea Sanger ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy ! ! Department of Politics University of Virginia ! ! ! ! !1 of !195 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! “The first person who, having fenced off a plot of ground, took it into his head to say this is mine and found people simple enough to believe him, was the true founder of civil society.”1 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 1 Jean-Jacques Rousseau, "Discourse on the Origins and Foundations of Inequality among Men" in The First and Second Discourses, ed. Roger D. Masters, trans. Roger D. Masters and Judith Masters (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1964), p. 141 cited in Wendy Brown, Walled States, Waning Sovereignty (Cambridge, Mass.: Zone Books; Distributed by the MIT Press, 2010). 43. !2 of !195 Table of Contents ! Introduction: International Frontiers and Property Rights 5 Alternative Explanations for Variance in States’ Property Preferences 8 Methodology and Research Design 22 The First Frontier: Three Phases of High Seas Preference Formation 35 The Age of Discovery: Iberian Appropriation and Dutch-English Resistance, Late-15th – Early 17th Centuries 39 Making International Law: Anglo-Dutch Competition over the Status of European Seas, 17th Century 54 British Hegemony and Freedom of the Seas, 18th – 20th Centuries 63 Conclusion: What We’ve Learned from the Long -

Capital As Process and the History of Capitalism

Jonathan Levy Capital as Process and the History of Capitalism In the wake of the Great Recession, a new cycle of scholarship opened on the history of American capitalism. This occurred, however, without much specification of the subject at hand. In this essay, I offer a conceptualization of capitalism, by focus- ing on its root—capital. Much historical writing has treated capital as a physical factor of production. Against such a “mate- rialist” capital concept, I define capital as a pecuniary process of forward-looking valuation, associated with investment. Engag- ing recent work across literatures, I try to show how this con- ceptualization of capital and capitalism helps illuminate many core dynamics of modern economic life. Keywords: capitalism, capital theory, economic thought, finance, Industrial Revolution, Keynes, money, slavery, Veblen ecently, the so-called new history of capitalism has helped bring Reconomic life back closer to the center of the professional historical agenda. But what further point might it now serve—especially for schol- ars toiling in the fields of business and economic history all the while independent of historiographical fashion and trend? In the wake of the U.S. financial panic of 2008 and the Great Reces- sion that followed, in the field of U.S. history a new cycle of scholarship on the history of American capitalism opened, but without all that much conceptualization of the subject at hand—capitalism. If there has been one shared impulse, it is probably the study of commodification. Follow the commodity wherever it may lead, across thresholds of space, time, and the ever-expanding boundaries of the market. -

UC Riverside Cliodynamics

UC Riverside Cliodynamics Title Capitalist Systems are Societal Constructs: Not “Clouds” or “Clocks,” but “City States”: A Review of Does Capitalism Have a Future? by Immanuel Wallerstein, Randall Collins, Michael Mann, Georgi Derluguian, and Craig Calhoun (Oxford University Press,... Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7z63z6jt Journal Cliodynamics, 6(2) Author Scott, Bruce Publication Date 2015 DOI 10.21237/C7clio6229140 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Cliodynamics: The Journal of Quantitative History and Cultural Evolution Capitalist Systems are Societal Constructs: Not “Clouds” or “Clocks,” but “City States” A Review of Does Capitalism Have a Future? by Immanuel Wallerstein, Randall Collins, Michael Mann, Georgi Derluguian, and Craig Calhoun (Oxford University Press, 2013) Bruce Scott Harvard University Does Capitalism Have a Future? is the work of five distinguished senior authors addressing the future of capitalism and its recent past. Their book warns that “something big looms on the horizon: a structural crisis much bigger than the recent great recession. Over the next three or four decades, capitalists of the world may simply find it impossible to make their usual investment decisions due to overcrowding of world markets and inadequate accounting for rising social costs. In this situation, capitalism would end in the frustration of the capitalists themselves.” The authors have chosen a very broad and important topic -

The Contradiction of Classical Liberalism and Libertarianism

The contradiction of classical liberalism and libertarianism blogs.lse.ac.uk/businessreview/2017/02/01/the-contradiction-of-classical-liberalism-and-libertarianism/ 2/1/2017 A standard assumption in policy analyses and political debates is that classical liberal or libertarian views represent a radical alternative to a progressive or egalitarian agenda. In the political arena, classical liberalism and libertarianism often inform the policy agenda of centre-right and far- right parties. They underpin laissez-faire policies and reject any redistributive action, including welfare state provisions and progressive taxation. This is motivated by a fundamental belief in the value of personal autonomy and protection from (unjustified) external interference, including from the state. It is difficult to overestimate the philosophical and political relevance of classical liberalism and libertarianism. President Trump’s proposal to repeal the “Affordable Care Act (Obamacare)”, for example, is clearly inspired by a libertarian philosophical outlook whereby “No person should be required to buy insurance unless he or she wants to” (Healthcare Reform to Make America Great Again ). More generally, in the last four decades the political consensus, and the spectrum of policy proposals and outcomes, has significantly moved in a less interventionist, more laissez faire direction. The centrality of classical liberal and libertarian views has been such that the historical period after the end of the 1970s – following the election of Margaret Thatcher in the UK and Ronald Reagan in the US – has come to be known as the “Neoliberal era”. Yet the very coherence of the classical liberal and libertarian view of society, and its consistency with the fundamental tenets of modern democracies, have been questioned.