The Right to Private Property

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Collective Ownership of the Earth Anna Stilz

BOOK SYMPOSIUM: ON GLOBAL JUSTICE On Collective Ownership of the Earth Anna Stilz n appealing and original aspect of Mathias Risse’s book On Global Justice is his argument for humanity’s collective ownership of the A earth. This argument focuses attention on states’ claims to govern ter- ritory, to control the resources of that territory, and to exclude outsiders. While these boundary claims are distinct from private ownership claims, they too are claims to control scarce goods. As such, they demand evaluation in terms of dis- tributive justice. Risse’s collective ownership approach encourages us to see the in- ternational system in terms of property relations, and to evaluate these relations according to a principle of distributive justice that could be justified to all humans as the earth’s collective owners. This is an exciting idea. Yet, as I argue below, more work needs to be done to develop plausible distribution principles on the basis of this approach. Humanity’s collective ownership of the earth is a complex notion. This is because the idea performs at least three different functions in Risse’s argument: first, as an abstract ideal of moral justification; second, as an original natural right; and third, as a continuing legitimacy constraint on property conventions. At the first level, collective ownership holds that all humans have symmetrical moral status when it comes to justifying principles for the distribution of earth’s original spaces and resources (that is, excluding what has been man-made). The basic thought is that whatever claims to control the earth are made, they must be compatible with the equal moral status of all human beings, since none of us created these resources, and no one specially deserves them. -

Modern-Day Slavery & Human Rights

& HUMAN RIGHTS MODERN-DAY SLAVERY MODERN SLAVERY What do you think of when you think of slavery? For most of us, slavery is something we think of as a part of history rather than the present. The reality is that slavery still thrives in our world today. There are an estimated 21-30 million slaves in the world today. Today’s slaves are not bought and sold at public auctions; nor do their owners hold legal title to them. Yet they are just as surely trapped, controlled and brutalized as the slaves in our history books. What does slavery look like today? Slaves used to be a long-term economic investment, thus slaveholders had to balance the violence needed to control the slave against the risk of an injury that would reduce profits. Today, slaves are cheap and disposable. The sick, injured, elderly and unprofitable are dumped and easily replaced. The poor, uneducated, women, children and marginalized people who are trapped by poverty and powerlessness are easily forced and tricked into slavery. Definition of a slave: A person held against his or her will and controlled physically or psychologically by violence or its threat for the purpose of appropriating their labor. What types of slavery exist today? Bonded Labor Trafficking A person becomes bonded when their labor is demanded This involves the transport and/or trade of humans, usually as a means of repayment of a loan or money given in women and children, for economic gain and involving force advance. or deception. Often migrant women and girls are tricked and forced into domestic work or prostitution. -

The Right to Reparations for Acts of Torture: What Right, What Remedies?*

96 STATE OF THE ART The right to reparations for acts of torture: what right, what remedies?* Dinah Shelton** 1. Introduction international obligation must cease and the In all legal systems, one who wrongfully wrong-doing state must repair the harm injures another is held responsible for re- caused by the illegal act. In the 1927 Chor- dressing the injury caused. Holding the zow Factory case, the PCIJ declared dur- wrongdoer accountable to the victim serves a ing the jurisdictional phase of the case that moral need because, on a practical level, col- “reparation … is the indispensable comple- lective insurance might just as easily provide ment of a failure to apply a convention and adequate compensation for losses and for fu- there is no necessity for this to be stated in ture economic needs. Remedies are thus not the convention itself.”1 Thus, when rights only about making the victim whole; they are created by international law and a cor- express opprobrium to the wrongdoer from relative duty imposed on states to respect the perspective of society as a whole. This those rights, it is not necessary to specify is incorporated in prosecution and punish- the obligation to afford remedies for breach ment when the injury stems from a criminal of the obligation, because the duty to repair offense, but moral outrage also may be ex- emerges automatically by operation of law; pressed in the form of fines or exemplary or indeed, the PCIJ has called the obligation of punitive damages awarded the injured party. reparation part of the general conception of Such sanctions express the social convic- law itself.2 tion that disrespect for the rights of others In a later phase of the same case, the impairs the wrongdoer’s status as a moral Court specified the nature of reparations, claimant. -

U-I-313/13-91 27 March 2014 Concurring Opinion of Judge Jan

U-I-313/13-91 27 March 2014 Concurring Opinion of Judge Jan Zobec 1. Although I voted for the Decision in its entirety and also concur to a certain degree with its underlying reasons, I wish to express, in my concurring opinion, my view on property taxes from the viewpoint of the constitutional guarantee of private property, especially the private property of residential real property. The applicants namely also referred to the fact that the real property tax excessively interferes with the constitutional guarantee of private property, and the Decision does not contain answers to these allegations. A few brief introductory thoughts on the importance of private property in the circle of civilisation to which we belong 2. Private property entails one of the central constitutional values and one of the pillars of western civilisation. Already the Magna Carta Libertatum or The Great Charter of the Liberties of England of 1215, which made the king's power subject to law and which entails the first step towards the implementation of the idea of the rule of law, contained numerous important safeguards of ownership – e.g. the principle that in order to increase the budget of the state it is necessary to obtain the approval of the representative body; the provision that the crown's officials must not seize anyone's movable property without immediate payment – unless the seller voluntarily agrees that the payment be postponed; it also ensured protection from unlawful deprivation of possession or (arbitrary) deprivation without a judicial decision.[1] The theory on property rights also occupies the central position in the political philosophy of John Locke, which inspired the American Revolution and was reflected in the Declaration of Independence. -

Teacher Lesson Plan an Introduction to Human Rights and Responsibilities

Teacher Lesson Plan An Introduction to Human Rights and Responsibilities Lesson 2: Introduction to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights Note: The Introduction to Human Rights and Responsibilities resource has been designed as two unique lesson plans. However, depending on your students’ level of engagement and the depth of content that you wish to explore, you may wish to divide each lesson into two. Each lesson consists of ‘Part 1’ and ‘Part 2’ which could easily function as entire lessons on their own. Key Learning Areas Humanities and Social Sciences (HASS); Health and Physical Education Year Group Years 5 and 6 Student Age Range 10-12 year olds Resources/Props • Digital interactive lesson - Introduction to Human Rights and Responsibilities https://www.humanrights.gov.au/introhumanrights/ • Interactive Whiteboard • Note-paper and pens for students • Printer Language/vocabulary Human rights, responsibilities, government, children’s rights, citizen, community, individual, law, protection, values, beliefs, freedom, equality, fairness, justice, dignity, discrimination. Suggested Curriculum Links: Year 6 - Humanities and Social Sciences Inquiry Questions • How have key figures, events and values shaped Australian society, its system of government and citizenship? • How have experiences of democracy and citizenship differed between groups over time and place, including those from and in Asia? • How has Australia developed as a society with global connections, and what is my role as a global citizen?” Inquiry and Skills Questioning • -

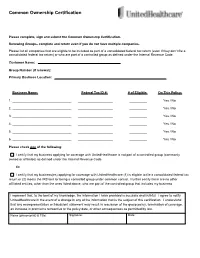

Common Ownership Form

Common Ownership Certification Please complete, sign and submit the Common Ownership Certification. Renewing Groups- complete and return even if you do not have multiple companies. Please list all companies that are eligible to be included as part of a consolidated federal tax return (even if they don’t file a consolidated federal tax return) or who are part of a controlled group as defined under the Internal Revenue Code. Customer Name: Group Number (if renewal): Primary Business Location: Business Name: Federal Tax ID #: # of Eligible: On This Policy: 1. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 2. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 3. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 4. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 5. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No 6. ___________________________ ________________ ________ Yes / No Please check one of the following: I certify that my business applying for coverage with UnitedHealthcare is not part of a controlled group (commonly owned or affiliates) as defined under the Internal Revenue Code. Or I certify that my business(es) applying for coverage with UnitedHealthcare (1) is eligible to file a consolidated federal tax return or (2) meets the IRS test for being a controlled group under common control. I further certify there are no other affiliated entities, other than the ones listed above, who are part of the controlled group that includes my business. I represent that, to the best of my knowledge, the information I have provided is accurate and truthful. I agree to notify UnitedHealthcare in the event of a change in any of the information that is the subject of this certification. -

Aristotle's Economic Defence of Private Property

ECONOMIC HISTORY ARISTOTLE ’S ECONOMIC DEFENCE OF PRIVATE PROPERTY CONOR MCGLYNN Senior Sophister Are modern economic justifications of private property compatible with Aristotle’s views? Conor McGlynn deftly argues that despite differences, there is much common ground between Aristotle’s account and contemporary economic conceptions of private property. The paper explores the concepts of natural exchange and the tragedy of the commons in order to reconcile these divergent views. Introduction Property rights play a fundamental role in the structure of any economy. One of the first comprehensive defences of the private ownership of property was given by Aristotle. Aris - totle’s defence of private property rights, based on the role private property plays in pro - moting virtue, is often seen as incompatible with contemporary economic justifications of property, which are instead based on mostly utilitarian concerns dealing with efficiency. Aristotle defends private ownership only insofar as it plays a role in promoting virtue, while modern defenders appeal ultimately to the efficiency gains from private property. However, in spite of these fundamentally divergent views, there are a number of similar - ities between the defence of private property Aristotle gives and the account of private property provided by contemporary economics. I will argue that there is in fact a great deal of overlap between Aristotle’s account and the economic justification. While it is true that Aristotle’s theory is quite incompatible with a free market libertarian account of pri - vate property which defends the absolute and inalienable right of an individual to their property, his account is compatible with more moderate political and economic theories of private property. -

Mill's "Very Simple Principle": Liberty, Utilitarianism And

MILL'S "VERY SIMPLE PRINCIPLE": LIBERTY, UTILITARIANISM AND SOCIALISM MICHAEL GRENFELL submitted for degree of Ph.D. London School of Economics and Political Science UMI Number: U048607 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U048607 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I H^S £ S F 6SI6 ABSTRACT OF THESIS MILL'S "VERY SIMPLE PRINCIPLE'*: LIBERTY. UTILITARIANISM AND SOCIALISM 1 The thesis aims to examine the political consequences of applying J.S. Mill's "very simple principle" of liberty in practice: whether the result would be free-market liberalism or socialism, and to what extent a society governed in accordance with the principle would be free. 2 Contrary to Mill's claims for the principle, it fails to provide a clear or coherent answer to this "practical question". This is largely because of three essential ambiguities in Mill's formulation of the principle, examined in turn in the three chapters of the thesis. 3 First, Mill is ambivalent about whether liberty is to be promoted for its intrinsic value, or because it is instrumental to the achievement of other objectives, principally the utilitarian objective of "general welfare". -

Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse

John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University Faculty Research Working Papers Series Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism Mathias Risse Nov 2003 RWP03-044 The views expressed in the KSG Faculty Research Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the John F. Kennedy School of Government or Harvard University. All works posted here are owned and copyrighted by the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. Can There be “Libertarianism without Inequality”? Some Worries About the Coherence of Left-Libertarianism1 Mathias Risse John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University October 25, 2003 1. Left-libertarianism is not a new star on the sky of political philosophy, but it was through the recent publication of Peter Vallentyne and Hillel Steiner’s anthologies that it became clearly visible as a contemporary movement with distinct historical roots. “Left- libertarian theories of justice,” says Vallentyne, “hold that agents are full self-owners and that natural resources are owned in some egalitarian manner. Unlike most versions of egalitarianism, left-libertarianism endorses full self-ownership, and thus places specific limits on what others may do to one’s person without one’s permission. Unlike right- libertarianism, it holds that natural resources may be privately appropriated only with the permission of, or with a significant payment to, the members of society. Like right- libertarianism, left-libertarianism holds that the basic rights of individuals are ownership rights. Left-libertarianism is promising because it coherently underwrites both some demands of material equality and some limits on the permissible means of promoting this equality” (Vallentyne and Steiner (2000a), p 1; emphasis added). -

Libra Dissertation.Pdf

! ! ! ! ! On the Origin of Commons: Understanding Divergent State Preferences Over Property Rights in New Frontiers ! Catherine Shea Sanger ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! A Dissertation Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy ! ! Department of Politics University of Virginia ! ! ! ! !1 of !195 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! “The first person who, having fenced off a plot of ground, took it into his head to say this is mine and found people simple enough to believe him, was the true founder of civil society.”1 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! 1 Jean-Jacques Rousseau, "Discourse on the Origins and Foundations of Inequality among Men" in The First and Second Discourses, ed. Roger D. Masters, trans. Roger D. Masters and Judith Masters (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1964), p. 141 cited in Wendy Brown, Walled States, Waning Sovereignty (Cambridge, Mass.: Zone Books; Distributed by the MIT Press, 2010). 43. !2 of !195 Table of Contents ! Introduction: International Frontiers and Property Rights 5 Alternative Explanations for Variance in States’ Property Preferences 8 Methodology and Research Design 22 The First Frontier: Three Phases of High Seas Preference Formation 35 The Age of Discovery: Iberian Appropriation and Dutch-English Resistance, Late-15th – Early 17th Centuries 39 Making International Law: Anglo-Dutch Competition over the Status of European Seas, 17th Century 54 British Hegemony and Freedom of the Seas, 18th – 20th Centuries 63 Conclusion: What We’ve Learned from the Long -

Intergovernmental Fiscal Immunity

BEST BEST & KRIEGER LLP A CALIFORNIA LIMITED LIABILITY PARTNERSHIP INCLUDING PROFESSIONAL CORPORATIONS RIVERSIDE ONTARIO LAWYERS (909) 686-1450 TH (909) 989-8584 WEST BROADWAY FLOOR ,, 402 , 13 ,, INDIAN WELLS SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA 92101-3542 ORANGE COUNTY (760) 568-2611 (619) 525-1300 (949) 263-2600 (619) 233-6118 FAX ,, SACRAMENTO BBKLAW COM . (916) 325-4000 CITY ATTORNEYS DEPARTMENT LEAGUE OF CALIFORNIA CITIES CONTINUING EDUCATION SEMINAR FEBRUARY 2003 WARREN DIVEN OF BEST BEST & KRIEGER LLP INTERGOVERNMENTAL FISCAL IMMUNITY TOPIC OUTLINE TAXES Property Taxes Publicly Owned Property as Generally Exempt from Property Taxation Construction of the Constitutional Exemption Use of Publicly Owned Property Property Owned by a Public Agency Outside its Jurisdictional Boundaries Taxation of Possessory Interest Miscellaneous Statutory Provisions or Decisions Related to Property Taxation Sales and Use Tax Business License Tax Special Taxes Utility Users Tax CAPITAL FACILITIES FEES Capital Facilities Fees - Judicial History Legislative Response to San Marcos USER FEES ASSESSMENTS Pre-Proposition 218 Implied Exemption Public Use Requirement Post Proposition 218 - What Effect Proposition 218? City Attorneys Department League of California Cities Continuing Education Seminar February 2003 Warren Diven Partner INTERGOVERNMENTAL FISCAL IMMUNITY1 The purpose of this paper is to review the concept of intergovernmental fiscal immunity, i.e., the exemption of one governmental entity from liability for the payment of taxes, assessments or fees levied or imposed by another governmental entity: • Where does such immunity exist? • How is such immunity created? • When does it apply? • What is the extent of such immunity? • What are the exceptions to the application of such immunity? This paper shall in turn review the application of intergovernmental fiscal immunity to: • Taxes; • Capital facility fees; • User fees; and • Assessments. -

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Universal Declaration of Human Rights Preamble Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world, Whereas disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind, and the advent of a world in which human beings shall enjoy freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want has been proclaimed as the highest aspiration of the common people, Whereas it is essential, if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human rights should be protected by the rule of law, Whereas it is essential to promote the development of friendly relations between nations, Whereas the peoples of the United Nations have in the Charter reaffirmed their faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person and in the equal rights of men and women and have determined to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom, Whereas Member States have pledged themselves to achieve, in cooperation with the United Nations, the promotion of universal respect for and observance of human rights and fundamental freedoms, Whereas a common understanding of these rights and freedoms is of the greatest importance for the full realization of this pledge, Now, therefore, The General Assembly, Proclaims this Universal Declaration of Human Rights as a common standard of achievement for all peoples and all nations, to the end that every individual and every organ of society, keeping this Declaration constantly in mind, shall strive by teaching and education to promote respect for these rights and freedoms and by progressive measures, national and international, to secure their universal and effective recognition and observance, both among the peoples of Member States themselves and among the peoples of territories under their jurisdiction.