Cree, Naskapi, Innu) with Julie Brittain and Marguerite Mackenzie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Death and Life for Inuit and Innu

skin for skin Narrating Native Histories Series editors: K. Tsianina Lomawaima Alcida Rita Ramos Florencia E. Mallon Joanne Rappaport Editorial Advisory Board: Denise Y. Arnold Noenoe K. Silva Charles R. Hale David Wilkins Roberta Hill Juan de Dios Yapita Narrating Native Histories aims to foster a rethinking of the ethical, methodological, and conceptual frameworks within which we locate our work on Native histories and cultures. We seek to create a space for effective and ongoing conversations between North and South, Natives and non- Natives, academics and activists, throughout the Americas and the Pacific region. This series encourages analyses that contribute to an understanding of Native peoples’ relationships with nation- states, including histo- ries of expropriation and exclusion as well as projects for autonomy and sovereignty. We encourage collaborative work that recognizes Native intellectuals, cultural inter- preters, and alternative knowledge producers, as well as projects that question the relationship between orality and literacy. skin for skin DEATH AND LIFE FOR INUIT AND INNU GERALD M. SIDER Duke University Press Durham and London 2014 © 2014 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Heather Hensley Typeset in Arno Pro by Copperline Book Services, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Sider, Gerald M. Skin for skin : death and life for Inuit and Innu / Gerald M. Sider. pages cm—(Narrating Native histories) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978- 0- 8223- 5521- 2 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn 978- 0- 8223- 5536- 6 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Naskapi Indians—Newfoundland and Labrador—Labrador— Social conditions. -

Jtc1/Sc2/Wg2 N3427 L2/08-132

JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3427 L2/08-132 2008-04-08 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Proposal to encode 39 Unified Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics in the UCS Source: Michael Everson and Chris Harvey Status: Individual Contribution Action: For consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC Date: 2008-04-08 1. Summary. This document requests 39 additional characters to be added to the UCS and contains the proposal summary form. 1. Syllabics hyphen (U+1400). Many Aboriginal Canadian languages use the character U+1428 CANADIAN SYLLABICS FINAL SHORT HORIZONTAL STROKE, which looks like the Latin script hyphen. Algonquian languages like western dialects of Cree, Oji-Cree, western and northern dialects of Ojibway employ this character to represent /tʃ/, /c/, or /j/, as in Plains Cree ᐊᓄᐦᐨ /anohc/ ‘today’. In Athabaskan languages, like Chipewyan, the sound is /d/ or an alveolar onset, as in Sayisi Dene ᐨᕦᐣᐨᕤ /t’ąt’ú/ ‘how’. To avoid ambiguity between this character and a line-breaking hyphen, a SYLLABICS HYPHEN was developed which resembles an equals sign. Depending on the typeface, the width of the syllabics hyphen can range from a short ᐀ to a much longer ᐀. This hyphen is line-breaking punctuation, and should not be confused with the Blackfoot syllable internal-w final proposed for U+167F. See Figures 1 and 2. 2. DHW- additions for Woods Cree (U+1677..U+167D). ᙷᙸᙹᙺᙻᙼᙽ/ðwē/ /ðwi/ /ðwī/ /ðwo/ /ðwō/ /ðwa/ /ðwā/. The basic syllable structure in Cree is (C)(w)V(C)(C). -

Native American Languages, Indigenous Languages of the Native Peoples of North, Middle, and South America

Native American Languages, indigenous languages of the native peoples of North, Middle, and South America. The precise number of languages originally spoken cannot be known, since many disappeared before they were documented. In North America, around 300 distinct, mutually unintelligible languages were spoken when Europeans arrived. Of those, 187 survive today, but few will continue far into the 21st century, since children are no longer learning the vast majority of these. In Middle America (Mexico and Central America) about 300 languages have been identified, of which about 140 are still spoken. South American languages have been the least studied. Around 1500 languages are known to have been spoken, but only about 350 are still in use. These, too are disappearing rapidly. Classification A major task facing scholars of Native American languages is their classification into language families. (A language family consists of all languages that have evolved from a single ancestral language, as English, German, French, Russian, Greek, Armenian, Hindi, and others have all evolved from Proto-Indo-European.) Because of the vast number of languages spoken in the Americas, and the gaps in our information about many of them, the task of classifying these languages is a challenging one. In 1891, Major John Wesley Powell proposed that the languages of North America constituted 58 independent families, mainly on the basis of superficial vocabulary resemblances. At the same time Daniel Brinton posited 80 families for South America. These two schemes form the basis of subsequent classifications. In 1929 Edward Sapir tentatively proposed grouping these families into superstocks, 6 in North America and 15 in Middle America. -

Agentive and Patientive Verb Bases in North Alaskan Inupiaq

AGENTTVE AND PATIENTIVE VERB BASES IN NORTH ALASKAN INUPIAQ A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the University of Alaska Fairbanks in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By TadatakaNagai, B.Litt, M.Litt. Fairbanks, Alaska May 2006 © 2006 Tadataka Nagai Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3229741 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UMI Microform 3229741 Copyright 2006 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. AGENTIVE AND PATIENTIYE VERB BASES IN NORTH ALASKAN INUPIAQ By TadatakaNagai ^ /Z / / RECOMMENDED: -4-/—/£ £ ■ / A l y f l A £ y f 1- -A ;cy/TrlHX ,-v /| /> ?AL C l *- Advisory Committee Chair Chair, Linguistics Program APPROVED: A a r// '7, 7-ooG Date Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. iii Abstract This dissertation is concerned with North Alaskan Inupiaq Eskimo. -

3. Naskapi Women: Words, Narratives, and Knowledge

chapter three Naskapi Women Words, Narratives, and Knowledge Carole Lévesque, Denise Geoffroy, and Geneviève Polèse By sharing their stories and knowledge, Naskapi women have played a key role in the reconstruction of the cultural and ecological heritage of their people. The Naskapi, who live in the subarctic region of the province of Québec, today represent about nine hundred people, most of whom reside in the village of Kawawachikamach, located about fifteen kilometres from the former mining town of Schefferville, along the 55th parallel (see map 3.1). The first written reports of the Naskapi date from the late eighteenth century. It appears that, at the time of the Europeans’ arrival, the peoples to whom these reports refer did not form a single, integrated group rather they were several groups of hunters who ranged across the northern portion of the Québec Labrador peninsula (Lévesque, Rains, and de Juriew 2001). The evidence suggests that these were families or groups of hunters of Innu origin who, sometime around the mid-eighteenth century, had apparently migrated to the hinterland of the subarctic region from the North Shore of the St. Lawrence (where several Innu bands had settled). Initially few in number, the Naskapi are said to have comprised about three hundred people around 1830 (Lévesque et al. 2001). 59 doi:10.15215/aupress/9781771990417.01 Ungava Bay Québec Fort Chimo Fort McKenzie Kawawachikamach Newfoundland and Labrador Québec Map 3.1 Location of the Naskapi village of Kawawachikamach, northern Québec. Source: Laboratoire d’analyse spatiale et d’économie urbaine et régionale, Institut national de la recherche scientifique, Montréal. -

Eskimo Language and Eskimo Song in Alaska: a Sociolinguistics of Deglobalisation in Endangered Language

Pragmatics 20:2.171-189 (2010) International Pragmatics Association ESKIMO LANGUAGE AND ESKIMO SONG IN ALASKA: A SOCIOLINGUISTICS OF DEGLOBALISATION IN ENDANGERED LANGUAGE Hiroko Ikuta Abstract Across Alaska, the popularity of indigenous forms of dance has risen, particularly in indigenous communities in which English dominates the heritage languages and Native youth have become monolingual English speakers. Some indigenous people say that Native dance accompanied by indigenous song is a way of preserving their endangered languages. With two case studies from Alaskan Eskimo communities, Yupiget on St. Lawrence Island and Iñupiat in Barrow, this article explores how use of endangered languages among Alaskan Eskimos is related to the activity of performing Eskimo dance. I suggest that practice of Eskimo dancing and singing that local people value as an important linguistic resource can be considered as a de-globalised sociolinguistic phenomenon, a process of performance and localisation in which people construct a particular linguistic repertoire withdrawn from globalisable circulation in multilingualism. Keywords: Deglobalisation; Globalisation; ‘Truncated multilingualism’; Endangered languages; Dance and song; Eskimo; Alaska. 1. Introduction In her excellent paper, Charlyn Dyers examines the development of multilingual repertoires among township dwellers in the Cape Town area of South Africa (Dyers 2008). While the situation can be seen upon superficial inspection as cases of language shift in South Africa, where speakers of various African languages shift to Afrikaans and to English, Dryers’s analysis reveals the emergence of ‘truncated multilingualism’ (see also Blommaert, Collins & Slembrouck 2005; and Blommaert 2010). Township dwellers do not entirely shift from one language to the other; instead, the different ingredients of their emerging multilingual repertoire are functionally developed in and distributed over separate domains of usage. -

ABOIUGINAL Comlmunity RELOCATION: the NASKAPI OF

ABOIUGINAL COMlMUNITY RELOCATION: THE NASKAPI OF NORTHEASTERN QUEBEC A Thesis Presented to The Facnlty of Graduate Studies of The University of Gnelph by REINE OLZVER In partial fulnllment of requirements for the degee of Master of Arts August, 1998 O Reine Oliver, 1998 National Library Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. nie W&ngton Ottawa ON K1A ON4 OttawaON K1AW canada canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Libray of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distniute or sell reproduire, prêter, distn'buer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni Ia thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT ABORIGINAL COMMUNM'Y RELOCATION: THE NASKAPI OF NORTBEASTERN QUEBEC Reine Oliver Advisor: University of Guelph, 1998 Professor David B. Knight This thesis is an investigation of the long term impacts of voluntary or community-initiated abonginal commdty relocations. The focw of the papa is the Naskapi relocation fkom Matimekosh to Kawawachikamach, concentrating on the social, cultural, politic& economic and health impacts the relocation has had on the community. -

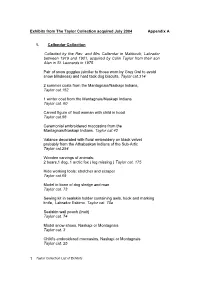

1 Exhibits from the Taylor Collection Acquired July 2004 Appendix a 1

Exhibits from The Taylor Collection acquired July 2004 Appendix A 1. Callendar Collection Collected by the Rev. and Mrs Callendar in Makkovik, Labrador between 1919 and 1921, acquired by Colin Taylor from their son Alan in St. Leonards in 1975 Pair of snow goggles (similar to those worn by Grey Owl to avoid snow blindness) and hard tack dog biscuits, Taylor cat.314 2 summer coats from the Mantagnais/Naskapi Indians, Taylor cat.152 1 winter coat from the Mantagnais/Naskapi Indians Taylor cat. 60 Carved figure of Inuit woman with child in hood Taylor cat.58 Ceremonial embroidered moccasins from the Mantagnais/Naskapi Indians, Taylor cat.42 Valance decorated with floral embroidery on black velvet probably from the Athabaskan Indians of the Sub-Artic Taylor cat.294 Wooden carvings of animals: 2 bears,1 dog, 1 arctic fox ( leg missing ) Taylor cat. 175 Hide working tools: stretcher and scraper Taylor cat.69 Model in bone of dog sledge and man Taylor cat. 73 Sewing kit in sealskin holder containing awls, hook and marking knife, Labrador Eskimo, Taylor cat. 70a Sealskin wall pouch (Inuit) Taylor cat. 74 Model snow shoes, Naskapi or Montagnais Taylor cat. 3 Child’s embroidered moccasins, Naskapi or Montagnais Taylor cat. 25 1 Taylor Collection List of Exhibits Man’s embroidered moccasins, Naskapi or Montagnais Taylor cat. 62 Child’s single embroidered moccasin, Naskapi or Montagnais Taylor cat. 234 Man’s embroidered moccasins, Naskapi or Montagnais Taylor cat. 143ii Woman’s embroidered moccasins, Naskapi or Montagnais, Taylor cat. 143i Woman’s embroidered moccasins, Taylor cat.202b Beaded pouch from the Mantagnais/Naskapi Indians Taylor cat. -

Cree-Naskapi (Of Quebec) Act Loi Sur Les Cris Et Les Naskapis Du Québec

CANADA CONSOLIDATION CODIFICATION Cree-Naskapi (of Quebec) Act Loi sur les Cris et les Naskapis du Québec S.C. 1984, c. 18 S.C. 1984, ch. 18 Current to November 9, 2016 À jour au 9 novembre 2016 Last amended on May 15, 2014 Dernière modification le 15 mai 2014 Published by the Minister of Justice at the following address: Publié par le ministre de la Justice à l’adresse suivante : http://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca http://lois-laws.justice.gc.ca OFFICIAL STATUS CARACTÈRE OFFICIEL OF CONSOLIDATIONS DES CODIFICATIONS Subsections 31(1) and (2) of the Legislation Revision and Les paragraphes 31(1) et (2) de la Loi sur la révision et la Consolidation Act, in force on June 1, 2009, provide as codification des textes législatifs, en vigueur le 1er juin follows: 2009, prévoient ce qui suit : Published consolidation is evidence Codifications comme élément de preuve 31 (1) Every copy of a consolidated statute or consolidated 31 (1) Tout exemplaire d'une loi codifiée ou d'un règlement regulation published by the Minister under this Act in either codifié, publié par le ministre en vertu de la présente loi sur print or electronic form is evidence of that statute or regula- support papier ou sur support électronique, fait foi de cette tion and of its contents and every copy purporting to be pub- loi ou de ce règlement et de son contenu. Tout exemplaire lished by the Minister is deemed to be so published, unless donné comme publié par le ministre est réputé avoir été ainsi the contrary is shown. -

Historic American Indian Tribes of Ohio 1654-1843

Historic American Indian Tribes of Ohio 1654-1843 Ohio Historical Society www.ohiohistory.org $4.00 TABLE OF CONTENTS Historical Background 03 Trails and Settlements 03 Shelters and Dwellings 04 Clothing and Dress 07 Arts and Crafts 08 Religions 09 Medicine 10 Agriculture, Hunting, and Fishing 11 The Fur Trade 12 Five Major Tribes of Ohio 13 Adapting Each Other’s Ways 16 Removal of the American Indian 18 Ohio Historical Society Indian Sites 20 Ohio Historical Marker Sites 20 Timeline 32 Glossary 36 The Ohio Historical Society 1982 Velma Avenue Columbus, OH 43211 2 Ohio Historical Society www.ohiohistory.org Historic American Indian Tribes of Ohio HISTORICAL BACKGROUND In Ohio, the last of the prehistoric Indians, the Erie and the Fort Ancient people, were destroyed or driven away by the Iroquois about 1655. Some ethnologists believe the Shawnee descended from the Fort Ancient people. The Shawnees were wanderers, who lived in many places in the south. They became associated closely with the Delaware in Ohio and Pennsylvania. Able fighters, the Shawnees stubbornly resisted white pressures until the Treaty of Greene Ville in 1795. At the time of the arrival of the European explorers on the shores of the North American continent, the American Indians were living in a network of highly developed cultures. Each group lived in similar housing, wore similar clothing, ate similar food, and enjoyed similar tribal life. In the geographical northeastern part of North America, the principal American Indian tribes were: Abittibi, Abenaki, Algonquin, Beothuk, Cayuga, Chippewa, Delaware, Eastern Cree, Erie, Forest Potawatomi, Huron, Iroquois, Illinois, Kickapoo, Mohicans, Maliseet, Massachusetts, Menominee, Miami, Micmac, Mississauga, Mohawk, Montagnais, Munsee, Muskekowug, Nanticoke, Narragansett, Naskapi, Neutral, Nipissing, Ojibwa, Oneida, Onondaga, Ottawa, Passamaquoddy, Penobscot, Peoria, Pequot, Piankashaw, Prairie Potawatomi, Sauk-Fox, Seneca, Susquehanna, Swamp-Cree, Tuscarora, Winnebago, and Wyandot. -

(Menziesia Ferruginea Smith): a UNIQUE REPORT of MYCOPHAGY on the CENTRAL and NORTH COASTS of BRITISH COLUMBIA

J. Ethnobiol. 15(1):89-98 Summer 1995 "GHOST'S EARS" (Exobasidium sp. affin. vaccinii) AND FOOL'S HUCKLEBERRIES (Menziesia ferruginea Smith): A UNIQUE REPORT OF MYCOPHAGY ON THE CENTRAL AND NORTH COASTS OF BRITISH COLUMBIA BRIAN D. COMPTON Department of Botany The University of British Columbia Vancouver, B.c., Canada V6T 124 ABSTRACT.-The cultural roles of mycocecidia (fungal galls) of the fungus Exo basidium sp. affin. vaccinii on Menziesia ferruginea Smith (false azalea, or fool's huckleberry) among various Pacific northwest coast cultures are identified and discussed. As many as nine distinct coastal groups named and ate these mycoce cidia. Among at least three coastal groups, the Henaaksiala, Heiltsuk, and Tsimshian, the mycocecidia had mythological importance. RESUMEN.-Se identifica y discute el papel cultural de las agallas producidas por el hongo Exobasidium sp. affin. vaccinii al crecer sobre Menziesia ferruginea (cuyos nombres vernaculos en ingles se traducen como "azalea falsa" y "arandano de tontos") entre las culturas de la costa noroccidental de Norteamerica. Nueve diferentes grupos de la costa nombraban y cornian estas agallas. Entre al menos tres grupos costeros, los Henaaksiala, Heiltsuk y Tsimshian, las agallas fungosas ternan importancia mitoI6gi.ca. RESUME.-Le champignon Exobasidium sp. affin. vaccinii produit des galles sur Menziesia ferruginea Smith ("fausse azalee"). Le role de ces galles dans la culture de differents peuples ou groupes autochtones de la cote nord-ouest du Pacifique est identitie et discute ici. Jusqu'a neuf de ces peuples ont nomme, et utilise les galles d'Exobasidium comme nourriture. Chez au moins trois groupes, les Henaak siala, les Heiltsuk et les Tsimshian, les galles avaient une importance' mytho logique. -

Challenges and Possibilities for St. Lawrence Island Yupik

Language Shift, Language Technology, and Language Revitalization: Challenges and Possibilities for St. Lawrence Island Yupik Lane Schwartz University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Department of Linguistics [email protected] Abstract St. Lawrence Island Yupik is a polysynthetic language indigenous to St. Lawrence Island, Alaska, and the Chukotka Peninsula of Russia. While the vast majority of St. Lawrence Islanders over the age of 40 are fluent L1 Yupik speakers, rapid language shift is underway among younger generations; language shift in Chukotka is even further advanced. This work presents a holistic proposal for language revitalization that takes into account numerous serious challenges, including the remote location of St. Lawrence Island and Chukotka, the high turnover rate among local teachers, socioeconomic challenges, and the lack of existing language learning materials. Keywords: St. Lawrence Island Yupik, language technology, language revitalization Piyuwhaaq Sivuqam akuzipiga akuzitngi qerngughquteghllagluteng ayuqut, Sivuqametutlu pamanillu quteghllagmillu. Akuzipikayuget kiyang 40 year-eneng nuyekliigut, taawangiinaq sukallunteng allanun ulunun lliighaqut nuteghatlu taghnughhaatlu; wataqaaghaq pa- mani quteghllagmi. Una qepghaqaghqaq aaptaquq ulum uutghutelleghqaaneng piyaqnaghngaan uglalghii ilalluku uyavantulanga Sivuqaaamllu Quteghllagemllu, apeghtughistetlu mulungigatulangitnengllu, kiyaghtaallghemllu allangughnenganengllu, enkaam apeghtuusipagitellghanengllu. 1. The Inuit-Yupik language family We therefore forgo the