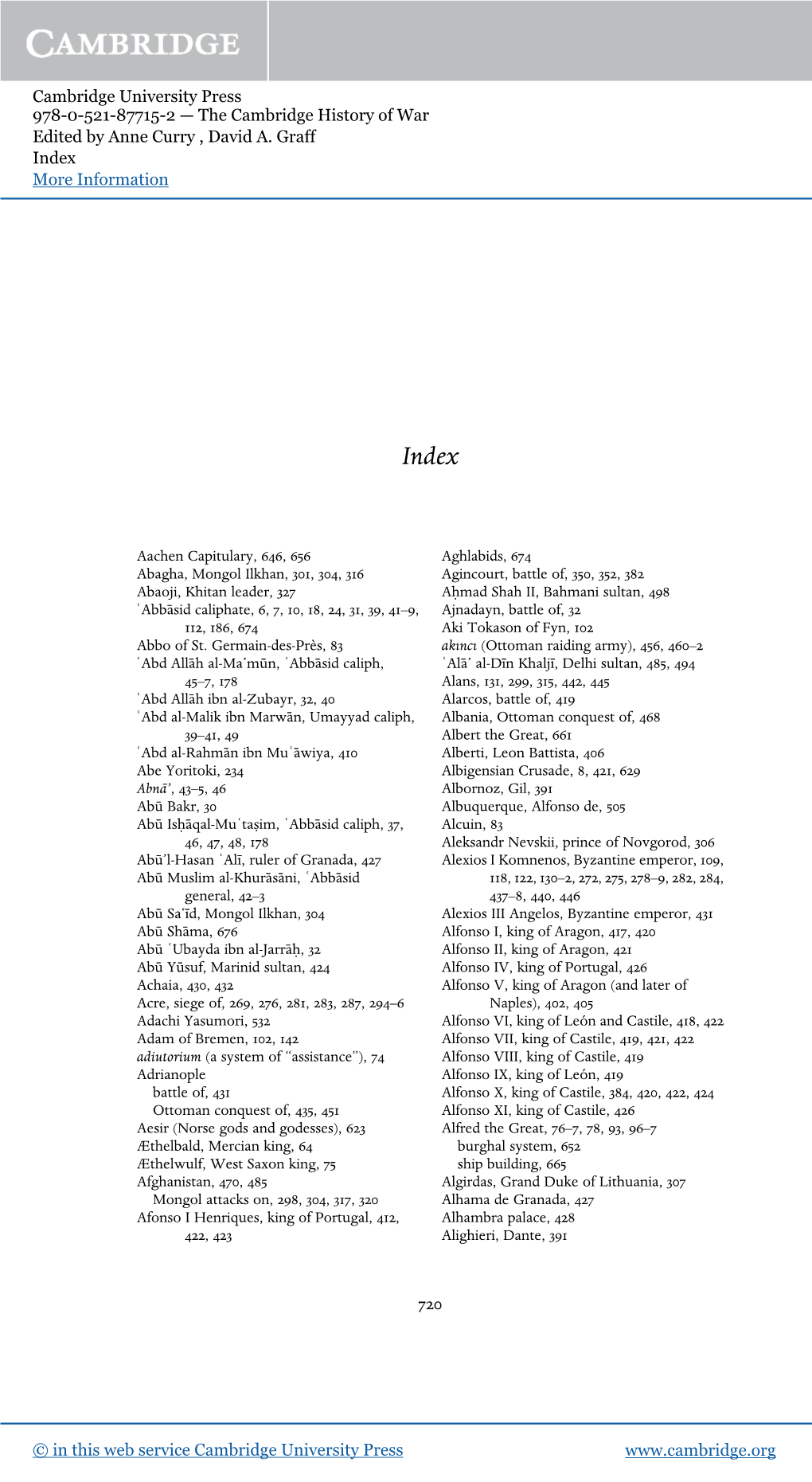

The Cambridge History of War Edited by Anne Curry , David A. Graff Index More Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANDEAN PREHISTORY – Online Course ANTH 396-003 (3 Credits

ANTH 396-003 1 Andean Prehistory Summer 2017 Syllabus ANDEAN PREHISTORY – Online Course ANTH 396-003 (3 credits) – Summer 2017 Meeting Place and Time: Robinson Hall A, Room A410, Tuesdays, 4:30 – 7:10 PM Instructor: Dr. Haagen Klaus Office: Robinson Hall B Room 437A E-Mail: [email protected] Phone: (703) 993-6568 Office Hours: T,R: 1:15- 3PM, or by appointment Web: http://soan.gmu.edu/people/hklaus - Required Textbook: Quilter, Jeffrey (2014). The Ancient Central Andes. Routledge: New York. - Other readings available on Blackboard as PDFs. COURSE OBJECTIVES AND CONTENTS This seminar offers an updated synthesis of the development, achievements, and the material, organizational and ideological features of pre-Hispanic cultures of the Andean region of western South America. Together, they constituted one of the most remarkable series of civilizations of the pre-industrial world. Secondary objectives involve: appreciation of (a) the potential and limitations of the singular Andean environment and how human inhabitants creatively coped with them, (b) economic and political dynamism in the ancient Andes (namely, the coast of Peru, the Cuzco highlands, and the Titicaca Basin), (c) the short and long-term impacts of the Spanish conquest and how they relate to modern-day western South America, and (d) factors and conditions that have affected the nature, priorities, and accomplishments of scientific Andean archaeology. The temporal coverage of the course span some 14,000 years of pre-Hispanic cultural developments, from the earliest hunter-gatherers to the Spanish conquest. The primary spatial coverage of the course roughly coincides with the western half (coast and highlands) of the modern nation of Peru – with special coverage and focus on the north coast of Peru. -

The Crimean Khanate, Ottomans and the Rise of the Russian Empire*

STRUGGLE FOR EAST-EUROPEAN EMPIRE: 1400-1700 The Crimean Khanate, Ottomans and the Rise of the Russian Empire* HALİL İNALCIK The empire of the Golden Horde, built by Batu, son of Djodji and the grand son of Genghis Khan, around 1240, was an empire which united the whole East-Europe under its domination. The Golden Horde empire comprised ali of the remnants of the earlier nomadic peoples of Turkic language in the steppe area which were then known under the common name of Tatar within this new political framework. The Golden Horde ruled directly över the Eurasian steppe from Khwarezm to the Danube and över the Russian principalities in the forest zone indirectly as tribute-paying states. Already in the second half of the 13th century the western part of the steppe from the Don river to the Danube tended to become a separate political entity under the powerful emir Noghay. In the second half of the 14th century rival branches of the Djodjid dynasty, each supported by a group of the dissident clans, started a long struggle for the Ulugh-Yurd, the core of the empire in the lower itil (Volga) river, and for the title of Ulugh Khan which meant the supreme ruler of the empire. Toktamish Khan restored, for a short period, the unity of the empire. When defeated by Tamerlane, his sons and dependent clans resumed the struggle for the Ulugh-Khan-ship in the westem steppe area. During ali this period, the Crimean peninsula, separated from the steppe by a narrow isthmus, became a refuge area for the defeated in the steppe. -

Steppe Nomads in the Eurasian Trade1

Volumen 51, N° 1, 2019. Páginas 85-93 Chungara Revista de Antropología Chilena STEPPE NOMADS IN THE EURASIAN TRADE1 NÓMADAS DE LA ESTEPA EN EL COMERCIO EURASIÁTICO Anatoly M. Khazanov2 The nomads of the Eurasian steppes, semi-deserts, and deserts played an important and multifarious role in regional, interregional transit, and long-distance trade across Eurasia. In ancient and medieval times their role far exceeded their number and economic potential. The specialized and non-autarchic character of their economy, provoked that the nomads always experienced a need for external agricultural and handicraft products. Besides, successful nomadic states and polities created demand for the international trade in high value foreign goods, and even provided supplies, especially silk, for this trade. Because of undeveloped social division of labor, however, there were no professional traders in any nomadic society. Thus, specialized foreign traders enjoyed a high prestige amongst them. It is, finally, argued that the real importance of the overland Silk Road, that currently has become a quite popular historical adventure, has been greatly exaggerated. Key words: Steppe nomads, Eurasian trade, the Silk Road, caravans. Los nómadas de las estepas, semidesiertos y desiertos euroasiáticos desempeñaron un papel importante y múltiple en el tránsito regional e interregional y en el comercio de larga distancia en Eurasia. En tiempos antiguos y medievales, su papel superó con creces su número de habitantes y su potencial económico. El carácter especializado y no autárquico de su economía provocó que los nómadas siempre experimentaran la necesidad de contar con productos externos agrícolas y artesanales. Además, exitosos Estados y comunidades nómadas crearon una demanda por el comercio internacional de bienes exóticos de alto valor, e incluso proporcionaron suministros, especialmente seda, para este comercio. -

The Image of the Cumans in Medieval Chronicles

Caroline Gurevich THE IMAGE OF THE CUMANS IN MEDIEVAL CHRONICLES: OLD RUSSIAN AND GEORGIAN SOURCES IN THE TWELFTH AND THIRTEENTH CENTURIES MA Thesis in Medieval Studies CEU eTD Collection Central European University Budapest May 2017 THE IMAGE OF THE CUMANS IN MEDIEVAL CHRONICLES: OLD RUSSIAN AND GEORGIAN SOURCES IN THE TWELFTH AND THIRTEENTH CENTURIES by Caroline Gurevich (Russia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner ____________________________________________ CEU eTD Collection Examiner Budapest May 2017 THE IMAGE OF THE CUMANS IN MEDIEVAL CHRONICLES: OLD RUSSIAN AND GEORGIAN SOURCES IN THE TWELFTH AND THIRTEENTH CENTURIES by Caroline Gurevich (Russia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Reader CEU eTD Collection Budapest May 2017 THE IMAGE OF THE CUMANS IN MEDIEVAL CHRONICLES: OLD RUSSIAN AND GEORGIAN SOURCES IN THE TWELFTH AND THIRTEENTH CENTURIES by Caroline Gurevich (Russia) Thesis -

The Faces of History. the Imagined Portraits of the Merovingian Kings at Versailles (1837-1842)

The faces of history. The imagined portraits of the Merovingian kings at Versailles (1837-1842) Margot Renard, University of Grenoble ‘One would expect people to remember the past and imagine the future. But in fact, when discoursing or writing about history, they imagine it in terms of their own experience, and when trying to gauge the future they cite supposed analogies from the past; till, by a double process of repeti- tion, they imagine the past and remember the future’. (Namier 1942, 70) The historian Christian Amalvi observes that during the first half of the nine- teenth century, most of the time history books presented a ‘succession of dyn- asties (Merovingians, Carolingians, Capetians), an endless row of reigns put end to end (those of the ‘rois fainéants’1 and of the last Carolingians especially), without any hierarchy, as a succession of fanciful portraits of monarchs, almost interchangeable’ (Amalvi 2006, 57). The Merovingian kings’ portraits, exhib- ited in the Museum of French History at the palace of Versailles, could be de- scribed similarly: they represent a succession of kings ‘put end to end’, with imagined ‘fanciful’ appearances, according to Amalvi. However, this vision dis- regards their significance for early nineteenth-century French society. Replac- ing these portraits in the broader context of contemporary history painting, they appear characteristic of a shift in historical apprehension. The French history painting had slowly drifted away from the great tradition established by Jacques-Louis David’s moralistic and heroic vision of ancient history. The 1820s saw a new formation of the historical genre led by Paul De- laroche's sentimental vision and attention to a realistic vision of history, restored to picturesqueness. -

Albanian Families' History and Heritage Making at the Crossroads of New

Voicing the stories of the excluded: Albanian families’ history and heritage making at the crossroads of new and old homes Eleni Vomvyla UCL Institute of Archaeology Thesis submitted for the award of Doctor in Philosophy in Cultural Heritage 2013 Declaration of originality I, Eleni Vomvyla confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signature 2 To the five Albanian families for opening their homes and sharing their stories with me. 3 Abstract My research explores the dialectical relationship between identity and the conceptualisation/creation of history and heritage in migration by studying a socially excluded group in Greece, that of Albanian families. Even though the Albanian community has more than twenty years of presence in the country, its stories, often invested with otherness, remain hidden in the Greek ‘mono-cultural’ landscape. In opposition to these stigmatising discourses, my study draws on movements democratising the past and calling for engagements from below by endorsing the socially constructed nature of identity and the denationalisation of memory. A nine-month fieldwork with five Albanian families took place in their domestic and neighbourhood settings in the areas of Athens and Piraeus. Based on critical ethnography, data collection was derived from participant observation, conversational interviews and participatory techniques. From an individual and family group point of view the notion of habitus led to diverse conceptions of ethnic identity, taking transnational dimensions in families’ literal and metaphorical back- and-forth movements between Greece and Albania. -

Illyrian-Albanian Continuity on the Areal of Kosova 29 Illyrian-Albanian Continuity on the Areal of Kosova

Illyrian-Albanian Continuity on the Areal of Kosova 29 Illyrian-Albanian Continuity on the Areal of Kosova Jahja Drançolli* Abstract In the present study it is examined the issue of Illyrian- Albanian continuity in the areal of Kosova, a scientific problem, which, due to the reasons of daily policy, has extremely become exploited (harnessed) until the present days. The politicisation of the ancient history of Kosova begins with the Eastern Crisis, a time when the programmes of Great-Serb aggression for the Balkans started being drafted. These programmes, inspired by the extra-scientific history dressed in myths, legends and folk songs, expressed the Serb aspirations to look for their cradle in Kosova, Vojvodina. Croatia, Dalmatia, Bosnia and Hercegovina and Montenegro. Such programmes, based on the instrumentalized history, have always been strongly supported by the political circles on the occasion of great historical changes, that have overwhelmed the Balkans. Key Words: Dardania and Dardans in antiquity, Arbers and Kosova during the Middle Ages, geopolitical, ethnic, religious and cultural concepts, which are known in the sources of that time followed by a chronological development. The region of Kosova preserves archeological monuments from the beginnings of Neolith (6000-2600 B.C.). Since that time the first settlements were constructed, including Tjerrtorja (Prishtinë), Glladnica (Graçanicë), Rakoshi (Istog), Fafos and Lushta (Mitrovicë), Reshtan and Hisar (Suharekë), Runik (Skenderaj) etc. The region of Kosova has since the Bronze Age been inhabited by Dardan Illyrians; the territory of extension of this region was much larger than the present-day territory of Kosova. * Prof. Jahja Drançolli Ph. D., Departament of History, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Pristina, Republic of Kosova, [email protected] Thesis Kosova, nr. -

The Eurasian Transformation of the 10Th to 13Th Centuries: the View from Song China, 906-1279

Haverford College Haverford Scholarship Faculty Publications History 2004 The Eurasian Transformation of the 10th to 13th centuries: The View from Song China, 906-1279 Paul Jakov Smith Haverford College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.haverford.edu/history_facpubs Repository Citation Smith, Paul Jakov. “The Eurasian Transformation of the 10th to 13th centuries: The View from the Song.” In Johann Arneson and Bjorn Wittrock, eds., “Eurasian transformations, tenth to thirteenth centuries: Crystallizations, divergences, renaissances,” a special edition of the journal Medieval Encounters (December 2004). This Journal Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History at Haverford Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Haverford Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Medieval 10,1-3_f12_279-308 11/4/04 2:47 PM Page 279 EURASIAN TRANSFORMATIONS OF THE TENTH TO THIRTEENTH CENTURIES: THE VIEW FROM SONG CHINA, 960-1279 PAUL JAKOV SMITH ABSTRACT This essay addresses the nature of the medieval transformation of Eurasia from the perspective of China during the Song dynasty (960-1279). Out of the many facets of the wholesale metamorphosis of Chinese society that characterized this era, I focus on the development of an increasingly bureaucratic and autocratic state, the emergence of a semi-autonomous local elite, and the impact on both trends of the rise of the great steppe empires that encircled and, under the Mongols ultimately extinguished the Song. The rapid evolution of Inner Asian state formation in the tenth through the thirteenth centuries not only swayed the development of the Chinese state, by putting questions of war and peace at the forefront of the court’s attention; it also influenced the evolution of China’s socio-political elite, by shap- ing the context within which elite families forged their sense of coorporate identity and calibrated their commitment to the court. -

IRK BİTİG Ve RUNİK HARFLİ METİNLERİN DİLİ

TC YILDIZ TEKNİK ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TÜRK DİLİ VE EDEBİYATI ANABİLİM DALI TÜRK DİLİ DOKTORA PROGRAMI DOKTORA TEZİ IRK BİTİG ve RUNİK HARFLİ METİNLERİN DİLİ FİKRET YILDIRIM 07725202 TEZ DANIŞMANI PROF. DR. MEHMET ÖLMEZ İSTANBUL 2013 Created by trial version, http://www.pdf-convert.com ÖZ IRK BİTİG ve RUNİK HARFLİ METİNLERİN DİLİ Hazırlayan Fikret Yıldırım Aralık, 2013 Kâğıda yazılı Eski Türkçe runik harfli metinleri ele aldığımız bu çalışmada öncelikle bu metinlerin bir envanteri hazırlanmıştır. Şu an Almanya, İngiltere, Japonya, Rusya ve Fransa’da bulunan toplam 46 adet katalog numaralı yazmanın transliterasyonu, transkripsiyonu ve Türkçe çevirileri verilmiştir. Bu yazmalar içinde en hacimlisi olan fal kitabı Irk Bitig üzerine açıklamalar da yapılmıştır. Bu açıklamalarda hem Irk Bitig’in hem de bununla bağlantılı olarak Eski Türkçenin kimi dil özellikleri üzerinde durulmuştur. Çalışmanın sonunda mevcut bütün kâğıda yazılı Eski Türkçe runik metinlerin sözlüğü verilmiştir. Anahtar Kelimeler : Irk Bitig, Eski Türkçe, Runik Metin, Envanter, Sözlük iii ABSTRACT IRK BİTİG and THE LANGUAGE of RUNIC MANUSCRIPTS Prepared by Fikret Yıldırım December, 2013 In this study, I dealt with Old Turkic runic manuscripts. Firstly, I prepared the inventory of Old Turkic runic manucripts. Now, there are 46 Old Turkic runic manuscripts with catalogue numbers which are preserved in Germany, England, Japan, Russia, and France. Also, I gave the transliteration, transcription and the Turkish translation of these manuscripts. Among these manuscripts, the voluminous one is the omen book, Irk Bitig. I also gave some remarks on this book. In these notes, I dealt with linguistic features of Irk Bitig parallel to Old Turkic. At the end of this study, I gave the vocabulary of Old Turkic runic manuscripts. -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal . -

Opfer Des Tatarenjochs Oder Besatzungsgewinner? Die Moskauer Großfürsten Und Die Goldene Horde in Der Darstellung Der Historiographie

Opfer des Tatarenjochs oder Besatzungsgewinner? Die Moskauer Großfürsten und die Goldene Horde in der Darstellung der Historiographie Diplomarbeit zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Magisters der Philosophie (Mag. Phil.) an der Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz vorgelegt von Bernard NIKOLLA am Institut für Geschichte Begutachter: Ass.-Prof. Mag. Dr. phil. Johannes Gießauf Graz, 2021 Eidesstattliche Erklärung Ich erkläre hiermit an Eides statt, dass ich die vorliegende Diplomarbeit selbständig und ohne Benutzung anderer als der angegebenen Hilfsmittel angefertigt habe. Die aus fremden Quellen direkt oder indirekt übernommenen Gedanken wurden als solche kenntlich gemacht. Diese Arbeit wurde in gleicher oder ähnlicher Form keiner anderen Prüfungsbehörde vorgelegt und auch noch nicht veröffentlicht. 17.05.2021 Datum, Ort Unterschrift Gendererklärung Aus Gründen der besseren Lesbarkeit wird auf die gleichzeitige Verwendung der Sprachformen männlich, weiblich und divers (m/w/d) verzichtet. Sämtliche Personenbezeichnungen gelten gleichermaßen für alle Geschlechter. Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Einleitung ............................................................................................................................... 7 2 Historischer Abriss der Goldenen Horde .......................................................................... 10 2.1 Tschinggis Khan und der Aufstieg des Mongolischen Reiches ..................................... 10 2.2 Der mongolische Vormarsch nach Europa .................................................................... -

Course Overview

COURSE OVERVIEW HISTORY 10 – HUMANITIES Early Medieval History COURSE DESCRIPTION Far from being a time of darkness as many have come to think of the Middle Ages, Medieval history plays a vital role in our understanding of the world today. The Medieval period from the time of Christ through the High Middle Ages is a fascinating world of flourishing culture from art, politics, warfare, literature, education, and science. It is during this age that we see the rise of soaring Cathedrals, new naval engineering, a grand synthesis of faith and reason, and the thriving of new arts and culture. Whether students are exploring the vast world of Byzantium, the Carolingian Dynasty, or the rise of Islam, they will be awed by the events of history and delighted to find just how connected and similar they are to our own world today. WHY WE TEACH IT The Middle Ages were an organic development of the Ancient world and as such, they deepen our understanding not merely of the period studied but everything that came afterward too. It is only by studying the men and cultures that came before us that we can properly interpret and understand our own. students will discover that the people of the Middle Ages are not as distant from our own time as we once thought. In fact, students may even discover that they have a great deal to teach us about how to live and flourish in our own contemporary society. KEY THEMES ● Struggle between Christianity and Paganism ● Developments of Christian Culture ● Flourishing of Art and Sciences as well as the horrible misconceptions caused by ignorance ● How the Medieval world shapes our own ● Wise peace and Just warfare COURSE MATERIALS ● Supplementary readings as handed out by the teacher.