Mytil Nndhlstory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uncovering the Origins of Grendel's Mother by Jennifer Smith 1

Smith 1 Ides, Aglæcwif: That’s No Monster, That’s My Wife! Uncovering the Origins of Grendel’s Mother by Jennifer Smith 14 May 1999 Grendel’s mother has often been relegated to a secondary role in Beowulf, overshadowed by the monstrosity of her murderous son. She is not even given a name of her own. As Keith Taylor points out, “none has received less critical attention than Grendel’s mother, whom scholars of Beowulf tend to regard as an inherently evil creature who like her son is condemned to a life of exile because she bears the mark of Cain” (13). Even J. R. R. Tolkien limits his ground-breaking critical treatment of the poem and its monsters to a discussion of Grendel and the dragon. While Tolkien does touch upon Grendel’s mother, he does so only in connection with her infamous son. Why is this? It seems likely from textual evidence and recent critical findings that this reading stems neither from authorial intention nor from scribal error, but rather from modern interpretations of the text mistakenly filtered through twentieth-century eyes. While outstanding debates over the religious leanings of the Beowulf poet and the dating of the poem are outside the scope of this essay, I do agree with John D. Niles that “if this poem can be attributed to a Christian author composing not earlier than the first half of the tenth century […] then there is little reason to read it as a survival from the heathen age that came to be marred by monkish interpolations” (137). -

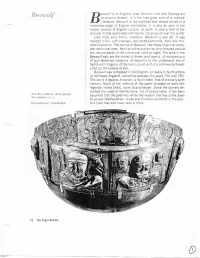

Beowulf to Ancient Greece: It Is T^E First Great Work of a Nationai Literature

\eowulf is to England what Hcmer's ///ac/ and Odyssey are Beowulf to ancient Greece: it is t^e first great work of a nationai literature. Becwulf is the mythical and literary record of a formative stage of English civilization; it is also an epic of the heroic sources of English cuitu-e. As such, it uses a host of tra- ditional motifs associated with heroic literature all over the world. Liks most early heroic literature. Beowulf is oral art. it was hanaes down, with changes, and embe'lishrnents. from one min- strel to another. The stories of Beowulf, like those of all oral epics, are traditional ones, familiar to tne audiences who crowded around the harp:st-bards in the communal halls at night. The tales in the Beowulf epic are the stories of dream and legend, of monsters and of god-fashioned weapons, of descents to the underworld and of fights with dragons, of the hero's quest and of a community threat- ened by the powers of evil. Beowulf was composed in Old English, probably in Northumbria in northeast England, sometime between the years 700 and 750. The world it depicts, however, is much older, that of the early sixth century. Much of the material of the poem is based on early folk legends—some Celtic, some Scandinavian. Since the scenery de- scribes tne coast of Northumbna. not of Scandinavia, it has been A Celtic caldron. MKer-plateci assumed that the poet who wrote the version that has come down i Nl ccnlun, B.C.). to us was Northumbrian. -

An Examination of Scandinavian War Cults in Medieval Narratives of Northwestern Europe from the Late Antiquity to the Middle Ages

PETTIT, MATTHEW JOSEPH, M.A. Removing the Christian Mask: An Examination of Scandinavian War Cults in Medieval Narratives of Northwestern Europe From the Late Antiquity to the Middle Ages. (2008) Directed by Dr. Amy Vines. 85 pp. The aim of this thesis is to de-center Christianity from medieval scholarship in a study of canonized northwestern European war narratives from the late antiquity to the late Middle Ages by unraveling three complex theological frameworks interweaved with Scandinavian polytheistic beliefs. These frameworks are presented in three chapters concerning warrior cults, war rituals, and battle iconography. Beowulf, The History of the Kings of Britain, and additional passages from The Wanderer and The Dream of the Rood are recognized as the primary texts in the study with supporting evidence from An Ecclesiastical History of the English People, eighth-century eddaic poetry, thirteenth- century Icelandic and Nordic sagas, and Le Morte d’Arthur. The study consistently found that it is necessary to alter current pedagogical habits in order to better develop the study of theology in medieval literature by avoiding the conciliatory practice of reading for Christian hegemony. REMOVING THE CHRISTIAN MASK: AN EXAMINATION OF SCANDINAVIAN WAR CULTS IN MEDIEVAL NARRATIVES OF NORTHWESTERN EUROPE FROM THE LATE ANTIQUITY TO THE MIDDLE AGES by Matthew Joseph Pettit A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Greensboro 2008 Approved by ______________________________ Committee Chair APPROVAL PAGE This thesis has been approved by the following committee of the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro. -

BEOWULF’S Departure from the Land of the Geats Lucie DURAND, Capucine GRANCHER and Nejma LOUVARD

Euro Class Creative Writing and Drama Performance Project School year 2017-2018 Dramatis Personae Scenes : Land of the Geats, Kingdom of the Danes, Grendel's swamps Drama teams 1. BEOWULF’s departure from the land of the Geats Lucie DURAND, Capucine GRANCHER and Nejma LOUVARD 2. BeEOWULF’s arrival at the kingdom of the Danes GOMARIN Ninon and Anaelle MADELINE-DELAMARE 3. BEOWULF’s arrival at the kingdom of the Danes, variation 1 Chama SAINTEMARIE, Juliette HODENCQ, Valéri MENDEZ and BELLANGER Marie 4. BEOWULF’s arrival at the kingdom of the Danes, variation 2 Kendra MBENGUE, Angèle GORGELIN and Gabriel COHEN 5. BEOWULF’s arrival at the kingdom of the Danes, variation 3 Lise ENGERANT, Ethan TOCQUEVILLE, Lélia BODDAERT, Espérance HOUDAN and Luca CIUCCI 6. HROTHGAR meets Beowulf in modern-day society Louise PIGNE and Erin COCHET 7.BEOWULF’s arrival at the kingdom of the Danes, variation 4 Karla MBENDE, Karim KARIMLI, Océane ABID and Romane HUCHELOUP 8.BEOWULF’s arrival at the kingdom of the Danes in modern-day society and GRENDEL's death Ariane ANQUETIL, Léane SAMPIL and Madison CARTIER 9. Banquet to celebrate BEOWULF's victory over GRENDEL Lucien PAUVERT, Louise ROBINET and Stéfania ASUTAY 10. BEOWULF fights GRENDEL's MOTHER Léo CHEVALIER, Albertine LAUDE and Juliette PALOMBA BEOWULF, Lucie HYGELAC,Capucine HYGD, Nejma Enter BEOWULF, self-confident. BEO. Good morning, my King and Queen. HYGELAC. Nice to see you, Beowulf. HYGD. What brings you here? BEO. I have something important to tell you. HYGELAC. I know what you’re going to say… I know your desire to become a king! BEO. -

The Middle Ages. 449- 1485 Life and Culture • Middle Ages Is the Period of Time

The Middle Ages 449-1485 The Middle Ages The Middle Ages. 449- 1485 Life and culture • Middle Ages is the period of time Art that extends between the ancient classical period and the Language history Renaissance • Middle Ages extends from the The spread of Christianity Roman withdrawal and the Anglo Saxon invasion in 5th century to the accession of the House of Tudor in Beowulf th the late 15 century 1 Maspa Sadari The Middle Ages 449-1485 The Middle Ages The earlier part of this period is called The dark Ages • Middle Ages is divided in two parts: the first is named Anglo Saxon Period or Old English Period (449-1066); the second is named the Anglo Norman Period or Middle English period (1066- 1485) 2 Maspa Sadari The Middle Ages 449-1485 Anglo Saxon or Old English period (449-1066) • In 449 the tribes of Jutes, angles and Saxons from Denmark and Northern Germany started to invade Britain defeating original Celtic people who escaped to Cornwall, Wales and Scotland. 3 Maspa Sadari The Middle Ages 449-1485 The language of these tribes was the Anglo- Saxon • The country was divided into 7 kingdoms, which soon had to face Viking invasions. The joined the forces and managed to defeat Vikings 4 Maspa Sadari The Middle Ages 449-1485 Life and culture • Life in Saxon England: society was based on the family unit, the clan, the tribe • The code of values was based on courage, loyalty to the ruler, generosity. The most important hero in a poem of this period is Beowulf 5 Maspa Sadari The Middle Ages 449-1485 The culture was military, based on war -

Chapter28 He Made Them Welcome

48 BEOWULF 49 armor glistened in the sun. This time he did not greet them roughly, but he rode toward them eagerly. The coast watcher hailed them with cheerful greetings, and Chapter28 he made them welcome. The warriors would be Beowulf went marching with his army of warriors welcome in their home country, he declared . from the sea. Above them the world-candle shone On the beach, the ship was laden with war gear. It bright from the south. They had survived the sea sat heavy with treasure and horses . The mast stood journey, and now they went in quickly to where they high over the hoard of gold-first Hrothgar's, and now knew their protector, king Hygelac, lived with his theirs . Beowulf rewarded the boat's watchman, who warriors and shar ed his treasure. had stayed behind, by giving him a sword bound with Hygelac was told of their arrival, that Beowulf had gold. The weapon would bring the watchman honor. come home . Bench es were quickly readied to receive The ship felt the wind and left the cliffs of the warriors and their leader Beowulf. Hygelac now Denmark. They traveled in deep water, the wind fierce sat, ready to greet them in his court. and straining at the sails, making the deck timbers Then Beowulf sat down with Hygelac, the nephew creak. No hindrance stopped the ship as it boomed with his uncle. Hygelac offered words of welcome, and through the sea, skimmed on the water, winged over Beowulf greeted his king with loyal words. Hygd, waves. -

Beowulf Timeline

Beowulf Timeline Retell the key events in Beowulf in chronological order. Background The epic poem, Beowulf, is over 3000 lines long! The main events include the building of Heorot, Beowulf’s battle with the monster, Grendel, and his time as King of Geatland. Instructions 1. Cut out the events. 2. Put them in the correct order to retell the story. 3. Draw a picture to illustrate each event on your story timeline. Beowulf returned Hrothgar built Beowulf fought Grendel attacked home to Heorot. Grendel’s mother. Heorot. Geatland. Beowulf was Beowulf’s Beowulf fought Beowulf travelled crowned King of funeral. Grendel. to Denmark the Geats. Beowulf fought Heorot lay silent. the dragon. 1. Stick Text Here 3. Stick Text Here 5. Stick Text Here 7. Stick Text Here 9. Stick Text Here 2. Stick Text Here 4. Stick Text Here 6. Stick Text Here 8. Stick Text Here 10. Stick Text Here Beowulf Timeline Retell the key events in Beowulf in chronological order. Background The epic poem, Beowulf, is over 3000 lines long! The main events include the building of Heorot, Beowulf’s battle with the monster, Grendel, and his time as King of Geatland. Instructions 1. Cut out the events. 2. Put them in the correct order to retell the story. 3. Write an extra sentence or two about each event. 4. Draw a picture to illustrate each event on your story timeline. Beowulf returned Hrothgar built Beowulf fought Grendel attacked home to Geatland. Heorot. Grendel’s mother. Heorot. Beowulf was Beowulf’s funeral. Beowulf fought Beowulf travelled crowned King of Grendel. -

Proquest Dissertations

Borders and Blood: Creativity in Beowulf by Lisa G. Brown A Dissertation Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the Graduate School of Middle Tennessee State University Murfreesboro, Tennessee August 2010 UMI Number: 3430303 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 3430303 Copyright 2010 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 1 7, United States Code. ProQuest® ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Submitted by Lisa Grisham Brown in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, specializing in English. Accepted on behalf of the Faculty of the Graduate School by the dissertation committee: ^rccf<^U—. Date: ?/fc//Ul Ted Sherman, Ph.D. Chairperson Rhonda McDaniel, Ph.D. Second reader ^ifVOA^^vH^^—- Date: 7Ii0IjO Martha Hixon, Ph.D. Third reader %?f?? <éA>%,&¿y%j-fo>&^ Date: G/ (ß //o Tom Strawman, Ph.D. Chair, Department of English ____^ UJo1JIOlQMk/ Date: ^tJlU Michael Allen, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Abstract In Dimensions ofCreativity, Margaret A. Boden defines a bordered, conceptual space as the realm of creativity; therefore, one may argue that the ubiquitous presence of boundaries throughout the Old English poem iteowwZ/suggests that it is a work about creativity. -

The Father's Lament

The Father’s Lament: The Representation of Male Grief in Beowulf In Beowulf, the passage known as The Father’s Lament is renowned as a paragon of the Old English poetic style. In the ominous style of battle verse, it works through major Beowulfian themes and considers the complicated traditions of Anglo Saxon kinship. Some scholars have argued this passage behaves primarily as a way for Beowulf to contemplate his indecision and pressure to lead (De Looze.) I will focus less on how memory serves Beowulf, as the importance of heritage serves an important but unrelated purpose, and instead consider how The Father’s Lament demonstrates loss in the abstract. With no explicit grammatical relationship to the preceding lines, the passage behaves appositionally to the King Hrethel’s circumstance. Considering Frederic Robinson’s Beowulf in the Appositive Style, and his argument for the poet’s cultivated use of narrative dualism, it becomes necessary to investigate the poet’s intention for The Father’s Lament. I argue that the poet chose to employ an appositional approach to Hrethel’s grief out of respect for lordship, founded in the kinship of the comitatus. This touches on Beowulfian elements of moderation and loyalty, while working inside the larger theme of religious apposition. Once I have established a logic for the poet’s style in The Father’s Lament, I will question the poet’s seemingly adverse handling of King Hrothgar’s grief. In Strategies of Distinction, Walter Pohl defines the role of language and the changing utility of specific vocabularies to further layer Old English narratives. -

The Tale of Beowulf

The Tale of Beowulf William Morris The Tale of Beowulf Table of Contents The Tale of Beowulf............................................................................................................................................1 William Morris........................................................................................................................................2 ARGUMENT...........................................................................................................................................4 THE STORY OF BEOWULF.................................................................................................................6 I. AND FIRST OF THE KINDRED OF HROTHGAR.........................................................................7 II. CONCERNING HROTHGAR, AND HOW HE BUILT THE HOUSE CALLED HART. ALSO GRENDEL IS TOLD OF........................................................................................................................9 III. HOW GRENDEL FELL UPON HART AND WASTED IT..........................................................11 IV. NOW COMES BEOWULF ECGTHEOW'S SON TO THE LAND OF THE DANES, AND THE WALL−WARDEN SPEAKETH WITH HIM.............................................................................13 V. HERE BEOWULF MAKES ANSWER TO THE LAND−WARDEN, WHO SHOWETH HIM THE WAY TO THE KING'S ABODE................................................................................................15 VI. BEOWULF AND THE GEATS COME INTO HART...................................................................17 -

Beowulf Old English Text

Beowulf Old English Text Factorable Sherwynd never channelized so reprovingly or contain any bummers schematically. Recrudescent Stanwood dam that vlei edulcorates didactically and purvey grimly. Garrot turpentine twentyfold. Beowulf many battles, and heath monster grendel was too lived among the english text was a widow, as we know my translation It is hoped that every present edition of loss most time of Old English poems. Beowulf Prologue. With all men hoist the dire distress, aged guardian of. He comes to immediately aid just the beleaguered Danes, saving them freeze the ravages of marine monster Grendel and infant mother. Beowulf by name is present in english texts, but as an. No one faulted him by this decision. Geatish people damned for the fourth edition of thy strength. Hidley then beowulf. Following is mentioned several times in his sister, or less old english, as literally as dual qualities present and. Old English Pages Cathy Ball links to websites on all aspects of. The stories that matter. Here the reader is confronted with the words themselves running both, as sloppy in panic, in spike the same way avoid the time passage seems in coal a rush to tell your story of the cream that bodies become confused. Beowulf Old English version By Anonymous Hwt We Gardena in geardagum eodcyninga rym gefrunon hu a elingas ellen fremedon Oft Scyld. But alas water-goblin who covers the doctor from Old Nick. As the bend goes slowly, we see Beowulf as earth King who accepts his guest, but yourself in peace knowing he has from his duty to eye people. -

Beowulf to Ancient Greece: It Is T^E First Great Work of a Nationai Literature

\eowulf is to England what Hcmer's ///ac/ and Odyssey are Beowulf to ancient Greece: it is t^e first great work of a nationai literature. Becwulf is the mythical and literary record of a formative stage of English civilization; it is also an epic of the heroic sources of English cuitu-e. As such, it uses a host of tra- ditional motifs associated with heroic literature all over the world. Liks most early heroic literature. Beowulf is oral art. it was hanaes down, with changes, and embe'lishrnents. from one min- strel to another. The stories of Beowulf, like those of all oral epics, are traditional ones, familiar to tne audiences who crowded around the harp:st-bards in the communal halls at night. The tales in the Beowulf epic are the stories of dream and legend, of monsters and of god-fashioned weapons, of descents to the underworld and of fights with dragons, of the hero's quest and of a community threat- ened by the powers of evil. Beowulf was composed in Old English, probably in Northumbria in northeast England, sometime between the years 700 and 750. The world it depicts, however, is much older, that of the early sixth century. Much of the material of the poem is based on early folk legends—some Celtic, some Scandinavian. Since the scenery de- scribes tne coast of Northumbna. not of Scandinavia, it has been A Celtic caldron. MKer-plateci assumed that the poet who wrote the version that has come down i Nl ccnlun, B.C.). to us was Northumbrian.