Grendel Thesis Actual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uncovering the Origins of Grendel's Mother by Jennifer Smith 1

Smith 1 Ides, Aglæcwif: That’s No Monster, That’s My Wife! Uncovering the Origins of Grendel’s Mother by Jennifer Smith 14 May 1999 Grendel’s mother has often been relegated to a secondary role in Beowulf, overshadowed by the monstrosity of her murderous son. She is not even given a name of her own. As Keith Taylor points out, “none has received less critical attention than Grendel’s mother, whom scholars of Beowulf tend to regard as an inherently evil creature who like her son is condemned to a life of exile because she bears the mark of Cain” (13). Even J. R. R. Tolkien limits his ground-breaking critical treatment of the poem and its monsters to a discussion of Grendel and the dragon. While Tolkien does touch upon Grendel’s mother, he does so only in connection with her infamous son. Why is this? It seems likely from textual evidence and recent critical findings that this reading stems neither from authorial intention nor from scribal error, but rather from modern interpretations of the text mistakenly filtered through twentieth-century eyes. While outstanding debates over the religious leanings of the Beowulf poet and the dating of the poem are outside the scope of this essay, I do agree with John D. Niles that “if this poem can be attributed to a Christian author composing not earlier than the first half of the tenth century […] then there is little reason to read it as a survival from the heathen age that came to be marred by monkish interpolations” (137). -

Constructing the Witch in Contemporary American Popular Culture

"SOMETHING WICKED THIS WAY COMES": CONSTRUCTING THE WITCH IN CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN POPULAR CULTURE Catherine Armetta Shufelt A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2007 Committee: Dr. Angela Nelson, Advisor Dr. Andrew M. Schocket Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Donald McQuarie Dr. Esther Clinton © 2007 Catherine A. Shufelt All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Angela Nelson, Advisor What is a Witch? Traditional mainstream media images of Witches tell us they are evil “devil worshipping baby killers,” green-skinned hags who fly on brooms, or flaky tree huggers who dance naked in the woods. A variety of mainstream media has worked to support these notions as well as develop new ones. Contemporary American popular culture shows us images of Witches on television shows and in films vanquishing demons, traveling back and forth in time and from one reality to another, speaking with dead relatives, and attending private schools, among other things. None of these mainstream images acknowledge the very real beliefs and traditions of modern Witches and Pagans, or speak to the depth and variety of social, cultural, political, and environmental work being undertaken by Pagan and Wiccan groups and individuals around the world. Utilizing social construction theory, this study examines the “historical process” of the construction of stereotypes surrounding Witches in mainstream American society as well as how groups and individuals who call themselves Pagan and/or Wiccan have utilized the only media technology available to them, the internet, to resist and re- construct these images in order to present more positive images of themselves as well as build community between and among Pagans and nonPagans. -

Beowulf Timeline

Beowulf Timeline Retell the key events in Beowulf in chronological order. Background The epic poem, Beowulf, is over 3000 lines long! The main events include the building of Heorot, Beowulf’s battle with the monster, Grendel, and his time as King of Geatland. Instructions 1. Cut out the events. 2. Put them in the correct order to retell the story. 3. Draw a picture to illustrate each event on your story timeline. Beowulf returned Hrothgar built Beowulf fought Grendel attacked home to Heorot. Grendel’s mother. Heorot. Geatland. Beowulf was Beowulf’s Beowulf fought Beowulf travelled crowned King of funeral. Grendel. to Denmark the Geats. Beowulf fought Heorot lay silent. the dragon. 1. Stick Text Here 3. Stick Text Here 5. Stick Text Here 7. Stick Text Here 9. Stick Text Here 2. Stick Text Here 4. Stick Text Here 6. Stick Text Here 8. Stick Text Here 10. Stick Text Here Beowulf Timeline Retell the key events in Beowulf in chronological order. Background The epic poem, Beowulf, is over 3000 lines long! The main events include the building of Heorot, Beowulf’s battle with the monster, Grendel, and his time as King of Geatland. Instructions 1. Cut out the events. 2. Put them in the correct order to retell the story. 3. Write an extra sentence or two about each event. 4. Draw a picture to illustrate each event on your story timeline. Beowulf returned Hrothgar built Beowulf fought Grendel attacked home to Geatland. Heorot. Grendel’s mother. Heorot. Beowulf was Beowulf’s funeral. Beowulf fought Beowulf travelled crowned King of Grendel. -

Deus Ex Machina? Witchcraft and the Techno-World Venetia Robertson

Deus Ex Machina? Witchcraft and the Techno-World Venetia Robertson Introduction Sociologist Bryan R. Wilson once alleged that post-modern technology and secularisation are the allied forces of rationality and disenchantment that pose an immense threat to traditional religion.1 However, the flexibility of pastiche Neopagan belief systems like ‘Witchcraft’ have creativity, fantasy, and innovation at their core, allowing practitioners of Witchcraft to respond in a unique way to the post-modern age by integrating technology into their perception of the sacred. The phrase Deus ex Machina, the God out of the Machine, has gained a multiplicity of meanings in this context. For progressive Witches, the machine can both possess its own numen and act as a conduit for the spirit of the deities. It can also assist the practitioner in becoming one with the divine by enabling a transcendent and enlightening spiritual experience. Finally, in the theatrical sense, it could be argued that the concept of a magical machine is in fact the contrived dénouement that saves the seemingly despondent situation of a so-called ‘nature religion’ like Witchcraft in the techno-centric age. This paper explores the ways two movements within Witchcraft, ‘Technopaganism’ and ‘Technomysticism’, have incorporated man-made inventions into their spiritual practice. A study of how this is related to the worldview, operation of magic, social aspect and development of self within Witchcraft, uncovers some of the issues of longevity and profundity that this religion will face in the future. Witchcraft as a Religion The categorical heading ‘Neopagan’ functions as an umbrella that covers numerous reconstructed, revived, or invented religious movements, that have taken inspiration from indigenous, archaic, and esoteric traditions. -

Surviving and Thriving in a Hostile Religious Culture Michelle Mitchell Florida International University, [email protected]

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 11-14-2014 Surviving and Thriving in a Hostile Religious Culture Michelle Mitchell Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI14110747 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the New Religious Movements Commons Recommended Citation Mitchell, Michelle, "Surviving and Thriving in a Hostile Religious Culture" (2014). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1639. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/1639 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida SURVIVING AND THRIVING IN A HOSTILE RELIGIOUS CULTURE: CASE STUDY OF A GARDNERIAN WICCAN COMMUNITY A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in RELIGIOUS STUDIES by Michelle Irene Mitchell 2014 To: Interim Dean Michael R. Heithaus College of Arts and Sciences This thesis, written by Michelle Irene Mitchell, and entitled Surviving and Thriving in a Hostile Religious Culture: Case Study of a Gardnerian Wiccan Community, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. _______________________________________ Lesley Northup _______________________________________ Dennis Wiedman _______________________________________ Whitney A. Bauman, Major Professor Date of Defense: November 14, 2014 The thesis of Michelle Irene Mitchell is approved. -

Episode #030 – the Inspiring Wendy Rule

“The Infinite and the Beyond” hosted by Chris Orapello Episode #030 – The Inspiring Wendy Rule 1 Episode #030 – The Inspiring Wendy Rule The Infinite and the Beyond An esoteric podcast for the introspective pagan mind hosted by Chris Orapello www.infinite-beyond.com Underline Theme: Awen and Inspiration Show Introduction MM, BB, 93, Hello and Welcome to the 30th Episode of “The Infinite and the Beyond,” an esoteric podcast for the introspective pagan mind. Where we explore a variety of topics which relate to life and one’s unique spiritual journey. I am your host Chris Orapello. Intro music by George Wood. In this episode… We speak with Australian Visionary Songstress Wendy Rule and get to enjoy some of her music. “Creator Destroyer” from her album The Wolf Sky “Guided by Venus” from her album Guided by Venus “My Sister the Moon” from her album Guided by Venus “The Wolf Sky (Live)” from her album Live at the Castle on the Hill “Circle Open (Live)” from her album Live at the Castle on the Hill We learn about the controversial, “King of the Witches,” Alex Sanders in A Corner in the Occult. In the spirit of creativity we learn about the Awen in The Essence of Magic, but first lets hear “Creator Destroyer” a haunting track by Wendy Rule. Featured Artist “Creator Destroyer” by Wendy Rule Interview Part 1 : Wendy Rule ➢ Wild, passionate and empowering, Australian Visionary Songstress Wendy Rule, weaves together music, mythology and ritual to take her audience on an otherworldly journey of depth and passion. Drawing on her deep love of Nature and lifelong fascination with the worlds of Faerie and Magic, Wendy’s songs combine irresistible melodies with rich aural textures and a rare personal honesty. -

An Examination of Societal Impacts on Gender Roles in American and English Witchcraft

Illinois Wesleyan University Digital Commons @ IWU Honors Projects Religion 4-18-2006 Who's in Charge? An Examination of Societal Impacts on Gender Roles in American and English Witchcraft Austin J. Buscher '06 Illinois Wesleyan University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/religion_honproj Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Buscher '06, Austin J., "Who's in Charge? An Examination of Societal Impacts on Gender Roles in American and English Witchcraft" (2006). Honors Projects. 6. https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/religion_honproj/6 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by faculty at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Who's In Charge? An Examination of Societal Impacts on Gender Roles in American and English Witchcraft Austin J. Buscher Senior Honors Research Carole Myscofski, Advisor th Received Research Honors April 18 , 2006 Ie INTRODUCTION Since its genesis in the 1970s, American Witchcraftl has shown itself to be one ofthe most forward-looking and tolerant religions in the area ofwomen's roles and gender theory. -

13 Reflections on Tolkien's Use of Beowulf

13 Reflections on Tolkien’s Use of Beowulf Arne Zettersten University of Copenhagen Beowulf, the famous Anglo-Saxon heroic poem, and The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien, “The Author of the Century”, 1 have been thor- oughly analysed and compared by a variety of scholars.2 It seems most appropriate to discuss similar aspects of The Lord of the Rings in a Festschrift presented to Nils-Lennart Johannesson with a view to his own commentaries on the language of Tolkien’s fiction. The immediate pur- pose of this article is not to present a problem-solving essay but instead to explain how close I was to Tolkien’s own research and his activities in Oxford during the last thirteen years of his life. As the article unfolds, we realise more and more that Beowulf meant a great deal to Tolkien, cul- minating in Christopher Tolkien’s unexpected edition of the translation of Beowulf, completed by J.R.R. Tolkien as early as 1926. Beowulf has always been respected in its position as the oldest Germanic heroic poem.3 I myself accept the conclusion that the poem came into existence around 720–730 A.D. in spite of the fact that there is still considerable debate over the dating. The only preserved copy (British Library MS. Cotton Vitellius A.15) was most probably com- pleted at the beginning of the eleventh century. 1 See Shippey, J.R.R. Tolkien: Author of the Century, 2000. 2 See Shippey, T.A., The Road to Middle-earth, 1982, Pearce, Joseph, Tolkien. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY Archives Doreen Valiente Papers, The Keep Archival Centre, Brighton. Feminist Archive North, Brotherton Library, University of Leeds. Feminist Archive South, Bristol University Library. Feminist Library, South London. Library of Avalon, Glastonbury. Museum of Witchcraft’s Library, Boscastle, England. Peter Redgrove Papers, University of Sheffeld’s Library. Robert Graves Papers, St. John’s College Library, Oxford University. Sisterhood and After: The Women’s Liberation Oral History Project, The British Library. Starhawk Collection, Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley. Women’s Library, London School of Economics Library. Primary Sources Amanda, “Greenham Festival of Life,” Pipes of PAN 7 (1982): 3. Anarchist Feminist Newsletter 3 (September 1977). Anon., You Can’t Kill the Spirit: Yorkshire Women Go to Greenham (S.L.: Bretton Women’s Book Fund, 1983). Anon., “Becoming a Pagan,” Greenleaf (5 November 1992). © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive 277 license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2020 S. Feraro, Women and Gender Issues in British Paganism, 1945–1990, Palgrave Historical Studies in Witchcraft and Magic, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-46695-4 278 BIBLIOGRAPHY “Aquarian Pagans,” The Cauldron 22 (Beltane 1981): 5. Arachne 1 (May Eve 1983). Arachne Collective, “Arachne Reborn,” Arachne 2 (1985): 1. Ariadne, “Progressive Wicca: The New Tradition,” Dragon’s Brew 3 (January 1991): 12–16. Asphodel, “Letter,” Revolutionary and Radical Feminist Newsletter 8 (1981). Asphodel, “Letters,” Wood and Water 2:1 (Samhain 1981): 24–25. Asphodel, “Womanmagic,” Spare Rib 110 (September 1981): 50–53. Asphodel, “Letter,” Matriarchy Research and Reclaim Network Newsletter 9 (Halloween 1982). Asphodel, “Feminism and Spirituality: A Review of Recent Publications 1975– 1981,” Women’s Studies International Forum 5:1 (1982): 103–108. -

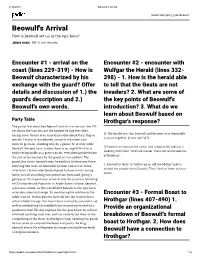

Beowulf's Arrival

2/16/2018 Beowulf's Arrival padlet.com/jenny_ryan/beowulf Beowulf's Arrival How is Beowulf set up as the epic hero? JENNY RYAN FEB 15, 2018 09:30AM Encounter #1 - arrival on the Encounter #2 - encounter with coast (lines 229-319) - How is Wulfgar the Herald (lines 332- Beowulf characterized by his 398) - 1. How is the herald able exchange with the guard? Offer to tell that the Geats are not details and discussion of 1.) the invaders? 2. What are some of guard's description and 2.) the key points of Beowulf's Beowulf's own words. introduction? 3. What do we learn about Beowulf based on Party Table Hrothgar's response? The guard rst describes Beowulf and his warriors on line 247. He claims the warriors are the boldest he had ever seen, 1) The herald saw that Beowulf and his men were honorable having never before seen armed men disembark their ship so and put together. (Lines 342-347). quickly. He also is immediately aware of the noble aura Beowulf gives off, claiming only by a glance he is truly noble. 2) Beowulf announces his name, and respectfully asks for a Beowulf, the epic hero, is described as so mighty that he is meeting with their “lord and master, the most renowned son easily recognizable as a great warrior, even distinguished from of Halfdane”. the rest of his warriors by the guard as true nobility. The guard also trusts Beowulf after he explains his business there, 3. Beowulf is there to “follow up an old friendship” and to believing him to be an honorable person who is true in his defend the people from Grendel. -

Mytil Nndhlstory

212 / Robert E. Bjork I chayter tt and Herebeald, the earlier swedish wars, and Daeghrefn, 242g-250ga; (26) weohstan,s slaying Eanmund in the second Swedish-wars-,2611-25a; of (27-29)Hygelac's fall, and the battle at Ravenswood in the earlier Swedish war, 2910b-98. 8. For a full discussion, see chapter I l. 9. The emendation was first suggested by Max Rieger (lg7l,4l4). MytIL nndHlstory D. Niles W loh, SU*Uryt Nineteenth-century interpret ations of B eowutf , puticululy mythology that was then in vogue' in Germany, fell underthe influence of the nature or Indo- More recently, some critics have related the poem to ancient Germanic feature b*op"un rnyih -O cult or to archetypes that are thought to be a universal of nu-un clnsciousness. Alternatively, the poem has been used as a source of the poem' knowledge concerning history. The search for either myth or history in useful however,-is attended by severe and perhaps insurmountable difficulties' More may be attempts to identify the poem as a "mythistory" that confirmed a set of fabulous values amongthe Anglo-saxons by connecting their current world to a ancesfral past. /.1 Lhronology 1833: Iohn Mitchell Kemble, offering a historical preface to his edition of the poem' locates the Geats in Schleswig. 1837: Kemble corrects his preface to reflect the influence of Jakob Grimm; he identifies the first "Beowulf" who figures in the poem as "Beaw," the agricultural deity. Karl Miillenhoff (1849b), also inspired by Grimm, identifies the poem as a Germanic meteorological myth that became garbled into a hero tale on being transplanted to England. -

Religion and the Return of Magic: Wicca As Esoteric Spirituality

RELIGION AND THE RETURN OF MAGIC: WICCA AS ESOTERIC SPIRITUALITY A thesis submitted for the degree of PhD March 2000 Joanne Elizabeth Pearson, B.A. (Hons.) ProQuest Number: 11003543 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11003543 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 AUTHOR’S DECLARATION The thesis presented is entirely my own work, and has not been previously presented for the award of a higher degree elsewhere. The views expressed here are those of the author and not of Lancaster University. Joanne Elizabeth Pearson. RELIGION AND THE RETURN OF MAGIC: WICCA AS ESOTERIC SPIRITUALITY CONTENTS DIAGRAMS AND ILLUSTRATIONS viii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ix ABSTRACT xi INTRODUCTION: RELIGION AND THE RETURN OF MAGIC 1 CATEGORISING WICCA 1 The Sociology of the Occult 3 The New Age Movement 5 New Religious Movements and ‘Revived’ Religion 6 Nature Religion 8 MAGIC AND RELIGION 9 A Brief Outline of the Debate 9 Religion and the Decline o f Magic? 12 ESOTERICISM 16 Academic Understandings of