The Imperial College Expedition, 1959 I75

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apus De Los Cuatro Suyos

! " " !# "$ ! %&' ()* ) "# + , - .//0 María Cleofé que es sangre, tierra y lenguaje. Silvia, Rodolfo, Hamilton Ernesto y Livia Rosa. A ÍNDICE Pág. Sumario 5 Introducción 7 I. PLANTEAMIENTO Y DISEÑO METODOLÓGICO 13 1.1 Aproximación al estado del arte 1.2 Planteamiento del problema 1.3 Propuesta metodológica para un nuevo acercamiento y análisis II. UN MODELO EXPLICATIVO SOBRE LA COSMOVISIÓN ANDINA 29 2.1 El ritmo cósmico o los ritmos de la naturaleza 2.2 La configuración del cosmos 2.3 El dominio del espacio 2.4 El ciclo productivo y el calendario festivo en los Andes 2.5 Los dioses montaña: intermediarios andinos III. LAS IDENTIDADES EN LOS MITOS DE APU AWSANGATE 57 3.1 Al pie del Awsangate 3.2 Awsangate refugio de wakas 3.3 De Awsangate a Qhoropuna: De los apus de origen al mundo de los muertos IV. PITUSIRAY Y EL TINKU SEXUAL: UNA CONJUNCIÓN SIMBÓLICA CON EL MUNDO DE LOS MUERTOS 93 4.1 El mito de las wakas Sawasiray y Pitusiray 4.2 El mito de Aqoytapia y Chukillanto 4.3 Los distintos modelos de la relación Sawasiray-Pitusiray 4.4 Pitusiray/ Chukillanto y los rituales del agua 4.5 Las relaciones urko-uma en el ciclo de Sawasiray-Pitusiray 4.6 Una homologación con el mito de Los Hermanos Ayar Anexos: El pastor Aqoytapia y la ñusta Chukillanto según Murúa El festival contemporáneo del Unu Urco o Unu Horqoy V. EL PODEROSO MALLMANYA DE LOS YANAWARAS Y QOTANIRAS 143 5.1 En los dominios de Mallmanya 5.2 Los atributos de Apu Mallmanya 5.3 Rivales y enemigos 5.4 Redes de solidaridad y alianzas VI. -

Sistematización Escoma Este Documento Está En Fase De

SISTEMATIZACIÓN ESCOMA ESTE DOCUMENTO ESTÁ EN FASE DE CONSTRUCCIÓN Sistematización Suches • Carátula • Créditos Índice Siglas Presentación 1. Ubicación y contexto del municipio de Escoma 1.1. Contexto ambiental 1.2. Municipio de Escoma 2. Mapeo de actores 3. Intervención 1. Pasos de la intervención 1.1. Paso 1: Socialización del proceso en territorio 1.2. Paso 2: Identificación de actores claves 1.3. Paso 3: Análisis de vulnerabilidad 1.4. Paso 4: Desarrollo de mapas comunitarios de riesgos 1.5. Paso 5: Desarrollo de protocolos de respuesta 1.6. Paso 6: Ejecución del simulacro 4. Lecciones aprendidas 5. Siguientes pasos Bibliografía Siglas y acrónimos ALT: Autoridad Binacional del Lago Tititaca CIIFEN: Centro Internacional para la Investigación del Fenómeno del Niño COE: Comité de Operaciones de Emergencia COEM: Comité de Operaciones de Emergencia Municipal COMURADE: Comités Municipales de Reducción de Riesgo y Atención de Desastres INE: Instituto Nacional de Estadística de Bolivia MMAyA: Ministerio de Medio Ambiente y Agua POA: Plan Operativo Anual PRASDES: Programa Regional Andino para el Fortalecimiento de los Servicios Meteorológicos, Hidrológicos, Climáticos y el Desarrollo SAT: Sistema de Alerta Temprana SENAMHI: Servicio Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología SIG: Sistema de Información Geográfica TDPS: Sistema Titicaca-Desaguadero-Poopó-Salar de Coipasa UE: Unidad Educativa UGR: Unidad de Gestión de Riesgos VIDECI: Viceministerio de Defensa Civil Presentación Desde noviembre de 2015 el Programa Regional Andino para el Fortalecimiento -

Las Relaciones Entre El Perú Y Bolivia (1826-2013)

Fabián Novak Sandra Namihas SERIE: POLÍTICA EXTERIOR PERUANA LAS RELACIONES ENTRE EL PERÚ Y BOLIVIA ( 1826-2013 ) SERIE: POLÍTICA EXTERIOR PERUANA LAS RELACIONES ENTRE EL PERÚ Y BOLIVIA (1826-2013) Serie: Política Exterior Peruana LAS RELACIONES ENTRE EL PERÚ Y BOLIVIA (1826-2013) Fabián Novak Sandra Namihas 2013 Serie: Política Exterior Peruana Las relaciones entre el Perú y Bolivia (1826-2013) Primera edición, octubre de 2013 © Konrad Adenauer Stiftung General Iglesias 630, Lima 18 – Perú Email: [email protected] URL: <www.kas.de/peru> Telf: (51-1) 208-9300 Fax: (51-1) 242-1371 © Instituto de Estudios Internacionales (IDEI) Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú Plaza Francia 1164, Lima 1 – Perú Email: [email protected] URL: <www.pucp.edu.pe/idei> Telf: (51-1) 626-6170 Fax: (51-1) 626-6176 Diseño de cubierta: Eduardo Aguirre / Sandra Namihas Derechos reservados, prohibida la reproducción de este libro por cualquier medio, total o parcialmente, sin permiso expreso de los editores. Hecho el depósito legal en la Biblioteca Nacional del Perú Registro: Nº 2013-14683 ISBN Nº 978-9972-671-18-0 Impreso en: EQUIS EQUIS S.A. RUC: 20117355251 Jr. Inca 130, Lima 34 – Perú Impreso en el Perú – Printed in Peru A la memoria de mi padre y hermano, F.N. A mis padres, Jorge y María Luisa S.N. Índice Introducción …………………………….……...…………….…… 17 CAPÍTULO 1: El inicio de ambas repúblicas y los grandes temas bilaterales en el siglo XIX ……………………….………..……… 19 1 El inicio de las relaciones diplomáticas y el primer intento de federación peruano-boliviana ……………............. 22 2 El comienzo del largo camino para la definición de los límites ……………………………………………...…. -

Bolivia 2006

ERlK MONASTERIO Bolivia 2006 Thanks are due to thejDlfowing contributors to these notes: Lindsay Griffin, John Biggar, Nick Flyvbjerg, Juliette Gehard, Arnaud Guilfaume, Moira Herring, Alain Mesili, Charlie Netherton and Katsutaka Yokoyama. Favourable weather conditions arrived early in the 2006 season with a premature end to the austral summer monsoon. As usual, most climbing activity was on the normal routes on Huayna Potosi, Illimani and Condoriri, but it was gratifying to see more trekking and climbing activity in the northern Cordillera Real, which has been quite neglected in recent years. Glacier conditions on the approaches to the western routes of Ancohuma and Illampu were by far the best seen over the past 10 years, as there were few crevasses and penitents, but the overall trend is still for rapid glacial recession. Unseasonably early snowfall arrived later in the season, substantially increasing the avalanche risk. Local guides say the climbing season is moving earlier each year. In 2005 the weather was almost continuously bad throughout September. The political situation is always important when it comes to planning a trip to Bolivia's Cordillera. The February 2006 democratic elections were unprecedented in terms of voter turnout, and for the first time elected as president an indigenous leader from a non-traditional party. Evo Morales won by a clear majority and formed a government with strong ideological affiliations to Venezuela and Cuba, rejecting US influence. This brought initial stability to the nation and the political demonstrations and strikes that in previous years paralysed the nation were not a problem during the May-September climbing season. -

The Making of a Legend

The Making of a Legend Colonel Fawcett in Bolivia 2 Rob Hawke THE MAKING OF A LEGEND: COLONEL FAWCETT IN BOLIVIA CONTENTS Introduction 4 PART ONE (1867-1914) 1. Early Life 5 2. Pathway to Adventure 6 3. Lawless Frontiers 7 4. A Lost World 18 5. An International Incident 24 6. In Search of Lost Cities 31 PART TWO (1915-1925 and Beyond) 7. The Final Curtain 36 8. Living Legend 38 9. Conclusions 41 APPENDIX 44 BIBLIOGRAPHY 45 PHOTO INDEX 46 3 “The jungle… it knows the secret of our fate. It makes no sign.” HM.Tomlinson, The Sea and the Jungle The original map for Exploration Fawcett, edited by Brian Fawcett 4 Introduction When the English Colonel Percy Harrison Fawcett failed to return from his 1925 expedition into the unexplored forests of the Brazilian interior, he vanished into the realm of legend. Fawcett was looking to make contact with a lost civilisation of highly advanced American Indians. The uncertainty of his fate, even 77 years on, has led to a number of hypotheses, some fantastical, some mundane, yet all shrouded in mystery. It is therefore not the purpose of this study to speculate upon his fate. The body of work on Fawcett is wafer thin in comparison to other explorers who became heroic through dying, such as Scott and Franklin, though his story is hardly less remarkable. Subsequent writing about Fawcett has naturally tended to focus on his disappearance, with little attention paid to his long and distinguished career as an explorer in Bolivia, which will provide the main focus of this study. -

Problemas Juridicos Que Plantea

PONTifiCIA UNIVE.R51UAD CATOLICA DEL PERU TE S 1 S EL APROVECHAMIENTP DE~ LAS .~GUAS DEL LAGO TITICACA Y LOS PROBLEMAS JURIDICOS QUE PLANTEA CARLOS RODRIGUEZ PASTOR MENDOZA LIMA - PERU 1 9 S 8 Ef aprovec~amíento· de (as aguas de( Lago Títícaca y (os prob(emas jurídicos que pían tea Los Gobiernos del Perú y de Bolivia han reconocido formal y s:>lem nemente, por virtud del Convenio suscrito en 1957 para el estudio del apro -vechamiento de las aguas del Lago Titicaca, el "condominio indivisible y exclusivo" que ambos países ejercen sobre ellas. Así las cosas, el presente trabajo encuentra su explicación tanto en la trascendencia jurídica dei problema y en la firme convicción del autor de que la realización de la obra en él tratada tiene insospechados alcances An lo que atañe al desarrollo industrial y al progreso del país, cuanto en la finaHdad práctica de borrar todo rezago de duda, de suspicacia o de vacilación que pudiera quedar en la opinión pública boliviana frente a~ Convenio aludido. Esto último, a raíz de determinada campaña presumible ·mente de buena fe, pero de tinte inocultablemente obstruccionista, llevada a cabo en esa República hermana bajo la invocación de un sentimiento nacio nalista, quizá estrecho y no siempre acertadamente inspirado. Creo que más que un compromiso oficial -ya felizmente logrado urge un acuerdo unánime de los pueblos, único medio de romper las barre _ras del prejuicio y de la indolencia que amenazan negativamente el éxito de la obra. Ni la revolución socio-económica planteada en Bolivia es, por sí sola, suficiente para resolver el grave problema de una masa indígena pauperi zada. -

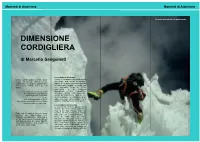

Dimensione Cordigliera

Momenti di Alpinismo Momenti di Alpinismo Scalata sui penitentes di Apolobamba DIMENSIONE CORDIGLIERA di Marcello Sanguineti La cordigliera del silenzio Dedico queste pagine a Yossi Brain, Provate a immaginare un mondo di valli caduto il 25 settembre 1999 sul Nevado dimenticate, una catena di montagne El Presidente (Cordigliera Apolobamba). glaciali che separa il desertico altopiano Il suo sorriso beffardo non è poi così boliviano dalle “yungas”, le umide gole lontano. che degradano verso la foresta amazzonica: è la Cordigliera ...non voglio vincere queste pareti, Apolobamba. Carte topografiche ma aggirarmi fra i loro precipizi incomplete e a volte errate, isolamento e e naufragare nei loro silenzi. scarsa documentazione caratterizzano Lo so, queste montagne, che offrono pareti mai sarà come riprendere un gioco: salite sulle quali aprire eleganti vie di dimenticato nelle pieghe della memoria, ghiaccio: un fantastico terreno di gioco. ma ancora ben vivo nel cuore... La cordigliera Apolobamba E’ una catena montuosa glaciale che si estende per circa ottanta chilometri a nord-est del lago Titicaca, vicino alla Dopo anni di vacanze estive in gruppi frontiera tra Perù e Bolivia; la maggior montuosi che rappresentano mete parte delle vette si trova in Bolivia o nei classiche dell’alpinismo extraeuropeo, pressi del confine fra i due Paesi. nel ’98 ho scelto con Alessandro Bianchi Diversamente dalle mete classiche delle (CAI ULE, Genova) due angoli appartati spedizioni alpinistiche in Sud America, è delle Ande Boliviane. Si è rivelata una poco frequentata e poco conosciuta, scelta davvero azzeccata… nonostante abbia caratteristiche simili a quelle delle cordigliere più famose (ad esempio, la Cordigliera Blanca e la Real). -

Proyecto De Grado

UNIVERSIDAD MAYOR DE SAN ANDRÉS FACULTAD DE HUMANIDADES Y CIENCIAS DE LA EDUCACIÓN CARRERA DE TURISMO MODELO DE GESTION ADMINISTRATIVA PARA EL DESARROLLO DEL TURISMO COMUNITARIO MENDIANTE LA IMPLEMENTACION DEL ALBERGUE HILO HILO PROYECTO DE GRADO POR: PAMELA MONTERO LOROÑO MIGUEL ANGEL TARIFA TUTOR : LIC. CARLOS PEREZ La Paz – Bolivia Febrero, 2012 1 Modelo de Gestión Administrativa para el Desarrollo de Turismo Comunitario mediante la Implementación del Albergue Turístico Hilo Hilo. Proyecto de Grado Índice General MARCO METODOLÓGICO 1. Introducción 1 2. Antecedentes 2 3. Justificación 6 4. Marco Conceptual 8 5. Marco Metodológico 32 DIAGNOSTICO 1. Análisis Externo 42 2. Análisis Interno 45 2.1 Ubicación Geográfica del Proyecto 45 2.2 Latitud y Longitud 45 2.3 Límites Territoriales 45 2.4 División Política Administrativa 45 2.5 Acceso a la zona del Proyecto 47 2.6 Administración y Gestión 47 3. Aspectos Físico-Naturales 48 3.1 Relieve y Topografía 48 3.2 Unidades Fisiográficas 48 3.3 Pisos Ecológicos 48 3.4 Clima 49 3.5 Flora y Vegetación 50 3.6 Fauna 52 3.7 Recursos Hídricos 54 3.8 Recursos Forestales 55 4. Aspectos Socio-Culturales 56 4.1 Aspectos Históricos 56 4.2 Demografía 58 4.2.1 Migración 59 4.2.2 Principales Indicadores Demográficos de la Población 59 4.3 Idioma 60 4.4 Identidad Cultural 62 4.5 Religiones y Creencias 62 4.6 Educación 63 4.6.1 N° de Matriculados por Sexo, Grado y Establecimiento 63 4.6.2 Deserción Escolar, Taza y principales causas 64 4.7 Salud 64 4.7.1 Medicina Tradicional 65 4.8 Aspecto Organizativo Institucional 65 2 Modelo de Gestión Administrativa para el Desarrollo de Turismo Comunitario mediante la Implementación del Albergue Turístico Hilo Hilo. -

Estrategias De Promocion Al

UNIVERSIDAD MAYOR DE SAN ANDRÉS FACULTAD DE HUMANIDADES Y CIENCIAS DE LA EDUCACIÓN CARRERA DE TURISMO PROYECTO DE GRADO “ESTRATEGIAS DE PROMOCION DEL TREK PELECHUCO-CURVA PARA EL DESARROLLO SOSTENIBLE EN EL ANMIN APOLOBAMBA” POSTULANTES: ROCIO MARTHA GUTIERREZ LLOTA JEANETT ALISON JALIRI QUISPE TUTOR: LIC. DANTE CAERO MIRANDA La Paz-Bolivia 2008 ESTRATEGIAS DE PROMOCION DEL TREKK PELUCHUCO-CURVA PARA EL DESARROLLO SOSTENIBLE EN EL ANMIN APOLOBAMBA INDICE CAPITULO I 1. ANTECEDENTES 2. DEFINICION CONCEPTUAL DEL AREA DE INVESTIGACION 3. FORMULACION DEL PROBLEMA DE LA INVESTIGACION 4. JUSTIFICACION 5. OBJETIVOS 6. MARCO METODOLOGICO 7. INSTRUMENTOS CAPTULO II MARCO CONCEPTUAL 2.1 PROMOCION 2.1.1. Marketing 2.1.2. Marketing Turístico 2.1.3. Estrategias 2.2 TURISMO 2.2.1 Turismo de Aventura 2.2.1.1 Trekking 2.3. SOSTENIBILIDAD 2.3.1. Turismo Sostenible ESTRATEGIAS DE PROMOCION DEL TREKK PELUCHUCO-CURVA PARA EL DESARROLLO SOSTENIBLE EN EL ANMIN APOLOBAMBA 2.3.2. Desarrollo Sostenible 2.3.2.1. Áreas Protegidas 2.3.3. Patrimonio Natural CAPITULO III DIAGNOSTICO 3.1 ANALISIS EXTERNO 3.1.1 Análisis Situacional Del Turismo 3.1.2. Turismo A Nivel Internacional. 3.1.3. Turismo En Latinoamérica. 3.1.4 Turismo En Bolivia. 3.1.5. Turismo En El Departamento De La Paz 3.1.6. Áreas Protegidas y el Turismo 3.2 ANALISIS INTERNO 3.2.1. Área Natural de Manejo Integrado Apolobamba 3.2.2 Aspectos Espaciales 3.2.2.1 Ubicación Geográfica 3.2.3. Aspectos físicos naturales 3.2.3.1. Clima. 3.2.3.2. Fauna. 3.2.3.3. -

486-496 Index AAJ-Lh1

INDEX COMPILED BY RALPH FERRARA AND EVE TALLMAN Mountains are listed by their official names and ranges; quotation marks indicate unofficial names. Ranges and geographic locations are also indexed. Unnamed peaks (e.g. Peak 2,340) are listed under P. Abbreviations are used for some states and countries and for the following: Article: art.; Cordillera: C.; Mountains: Mts.; National Park: Nat’l Park; Obituary: obit. Most per- sonnel are listed for major articles. Expedition leaders and persons supplying information in Climbs and Expeditions are also cited here. Indexed photographs are listed in bold type. Reviewed books are listed alphabetically under Book Reviews. Araiz, Iñaki 288 A Arbones, Toni 362-3 Aberger, Johann 227 Arch Canyon (UT) 176 Abi Gamin (Central Garhwal, India) 381 Arches Nat’l Park (UT) 175 Achey, Jeff 181, 271 Ares Tower (WA) 157 Ackroyd, Peter 391-3, 476-7 Argan Kangri (Ladakh, India) 369-70 Aconcagua (Argentina) 304-7, 306 Argentiere Peak “P.9,620” (Tordrillo Mts., AK) 210, 210 Acopán Tepui (Venezuela) 296-8 Argentina 302-24 Adamant Group (Selkirk Mts., CAN) 233-4 Arizona 174 Afghanistan 344-6 Armed Forces, P.(Tajikistan) 352-3 Africa 332-9 Arran, Anne 296-8 Agdlerussakasit (Greenland) 266-9 Arran, John 296-8 Agrada (Siberia, Russia) 343-4 Arunachal Pradesh (India) 386-7 Ak Su (Kyrgyzstan) 350-2, 351 Asgard, Mt. (Baffin Is., CAN) 222 Akela Qilla “CB 46” (Lahul, India) 373-4 Ashagiri (Lahul, India) 374 Aklangam (Kashgar Range, China) 418 Ashlu, Mt. (B.C., CAN) 230 Alaska 186-218 Asnococha (C. Apolobamba, Peru) 295 Alaska Range (AK) 186-211 Athearn, Lloyd 465-7 Alberta, Mt. -

TDPS 0011 Estudio De Hidrologia

COMISION DE ,. « ,. .. REPUBLICAS LAS COMUNIDADES * ,. DE EUROPEAS . ,. * ,. * PERU Y BOLIVIA CONVENIOS ALA /86/03 YALA /87 /23 - PERU YBOLIVIA '--..' PLAN DIRECTOR GLOBAL BINACIONAL DE PROTECCION - PREVENCION DE INUNDACIONES Y APROVECHAMIENTO DE LOS RECURSOS DEL LAGO TITICACA, RIO DESAGUADERO, LAGO POOPO Y LAGO SALAR DE COIPASA (SISTEMA T.D.P.S.) '- ESTUDIOS DE HIDROLOGIA Julio 1993 cnr COMP"CNll N,-,ll(}NAL( DlJ RII()~I I N D ICE o. LA REGION DEL PROYECTO 1. INTRODUCCION 2. ZONIFICACION HIDROLOGICA 2.1. ASPECTOS GENERALES 2.2. INFORMACION CARTOGRAPICA 2.3. DESCRIPCION GENERAL DEL SISTEMA TDPS 2.4. DISCRETIZACION DEL SISTEMA TOPS 2.5. CRITERIOS Y PARAMETROS UTILIZAOOS PARA LA CARACTERIZACION DE LAS ZONAS HIOROLOGICAS. 2.6. DESCRIPCION DE LAS ZONAS HIDROLOGICAS 2.6.1. Zona 1: Ramis 2.6.2. Zona 2: Buancane 2.6.3. Zona 3: Suchez 2.6.4. Zona 4: Coata 2.6.5. Zona 5: I1ave 2.6.6. Zona 6: Titicaca 2.6.6.1. Subzona 6A.: Huaycho 2.6.6.2. Subzona 6B: I11pa 2.6.6.3. Subzona 6C: Keka 2.6.6.4. Subzona 6D: Catari 2.6.6.5. Subzona 6E: Tiahuanacu 2.6.6.6. Subzona 6F: Zapatilla 2.6.7. Zona 7: Alto Desaguadero 2.6.8. Zona 8: Mauri 2.6.9. Zona 9: Media Desaguadero 2.6.10. Zona 10: PoopO-Sa1ares 2.6.10.1. Subzona lOA: Poopo 2.6.10.2. Subzona lOB: Salares 3 . ESTUDIO DE APORTACIONES 3.1. ASPECTOS GENERALES 3.2. ANALISIS DE LA RED FORONOMICA 3.3. DATOS DISPONIBLES 3.4. ELABORACION, CONTRASTE Y CORRECCION DE LAS SERIES HISTORICAS 3.4.1. -

Gaceta Oficial Del Gobierno Autónomo Departamental De La Paz Decreto - 018

GACETA OFICIAL DEL GOBIERNO AUTÓNOMO DEPARTAMENTAL DE LA PAZ DECRETO - 018 DECRETO DEPARTAMENTAL Nro. 018 CESAR HUGO COCARICO YANA GOBERNADOR DEL DEPARTAMENTO DE LA PAZ CONSIDERANDO: Que, la Constitución Política del Estado, en su Artículo 270, dispone que “Los principios que rigen la organización territorial de las entidades territoriales descentralizadas y autónomas son: la unidad, voluntariedad, solidaridad, equidad, bien común, autogobierno…” Que, el Artículo 232, de la Constitución Política del Estado, establece que la Administración Pública se rige por los principios de legitimidad, legalidad, imparcialidad, publicidad, compromiso e interés social, ética, transparencia, igualdad, competencia, eficiencia, calidad, calidez, honestidad, responsabilidad y resultados. Que, la Constitución Política del Estado en su Artículo 300 Par. I. determina que son competencias exclusivas de los gobiernos departamentales autónomos en su jurisdicción: Núm. 20. Políticas de turismo departamental. Que, la Ley No. 031, Marco de Autonomías y Descentralización “Andrés Ibáñez”, en su Artículo 95 (Turismo). Par. II. Dispone que de acuerdo a la competencia del Numeral 20, Parágrafo I del Artículo 300, de la Constitución Política del Estado, los gobiernos departamentales autónomos tendrán las siguientes competencias exclusivas: 2. Establecer políticas de turismo departamental en el marco de la política general de turismo. 3. Promoción de políticas de turismo departamental. Que, la Disposición Transitoria Décima Segunda en su Par. I. Núm. 2 de la Ley Marco de Autonomías y Descentralización, establece que se sustituye en lo que corresponda Prefectura Departamental por Gobierno Autónomo Departamental. Que, la Ley No. 2074 “Ley de Promoción y Desarrollo de la Actividad Turística en Bolivia, en su Artículo 9, Prefecturas, determina que las Prefecturas Departamentales, en tanto representantes del Poder Ejecutivo central, ejecutan y administran programas y proyectos de promoción y desarrollo turístico, emanados por el ente rector en estrecha coordinación con los Gobiernos Municipales.