The Making of a Legend

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apus De Los Cuatro Suyos

! " " !# "$ ! %&' ()* ) "# + , - .//0 María Cleofé que es sangre, tierra y lenguaje. Silvia, Rodolfo, Hamilton Ernesto y Livia Rosa. A ÍNDICE Pág. Sumario 5 Introducción 7 I. PLANTEAMIENTO Y DISEÑO METODOLÓGICO 13 1.1 Aproximación al estado del arte 1.2 Planteamiento del problema 1.3 Propuesta metodológica para un nuevo acercamiento y análisis II. UN MODELO EXPLICATIVO SOBRE LA COSMOVISIÓN ANDINA 29 2.1 El ritmo cósmico o los ritmos de la naturaleza 2.2 La configuración del cosmos 2.3 El dominio del espacio 2.4 El ciclo productivo y el calendario festivo en los Andes 2.5 Los dioses montaña: intermediarios andinos III. LAS IDENTIDADES EN LOS MITOS DE APU AWSANGATE 57 3.1 Al pie del Awsangate 3.2 Awsangate refugio de wakas 3.3 De Awsangate a Qhoropuna: De los apus de origen al mundo de los muertos IV. PITUSIRAY Y EL TINKU SEXUAL: UNA CONJUNCIÓN SIMBÓLICA CON EL MUNDO DE LOS MUERTOS 93 4.1 El mito de las wakas Sawasiray y Pitusiray 4.2 El mito de Aqoytapia y Chukillanto 4.3 Los distintos modelos de la relación Sawasiray-Pitusiray 4.4 Pitusiray/ Chukillanto y los rituales del agua 4.5 Las relaciones urko-uma en el ciclo de Sawasiray-Pitusiray 4.6 Una homologación con el mito de Los Hermanos Ayar Anexos: El pastor Aqoytapia y la ñusta Chukillanto según Murúa El festival contemporáneo del Unu Urco o Unu Horqoy V. EL PODEROSO MALLMANYA DE LOS YANAWARAS Y QOTANIRAS 143 5.1 En los dominios de Mallmanya 5.2 Los atributos de Apu Mallmanya 5.3 Rivales y enemigos 5.4 Redes de solidaridad y alianzas VI. -

Sistematización Escoma Este Documento Está En Fase De

SISTEMATIZACIÓN ESCOMA ESTE DOCUMENTO ESTÁ EN FASE DE CONSTRUCCIÓN Sistematización Suches • Carátula • Créditos Índice Siglas Presentación 1. Ubicación y contexto del municipio de Escoma 1.1. Contexto ambiental 1.2. Municipio de Escoma 2. Mapeo de actores 3. Intervención 1. Pasos de la intervención 1.1. Paso 1: Socialización del proceso en territorio 1.2. Paso 2: Identificación de actores claves 1.3. Paso 3: Análisis de vulnerabilidad 1.4. Paso 4: Desarrollo de mapas comunitarios de riesgos 1.5. Paso 5: Desarrollo de protocolos de respuesta 1.6. Paso 6: Ejecución del simulacro 4. Lecciones aprendidas 5. Siguientes pasos Bibliografía Siglas y acrónimos ALT: Autoridad Binacional del Lago Tititaca CIIFEN: Centro Internacional para la Investigación del Fenómeno del Niño COE: Comité de Operaciones de Emergencia COEM: Comité de Operaciones de Emergencia Municipal COMURADE: Comités Municipales de Reducción de Riesgo y Atención de Desastres INE: Instituto Nacional de Estadística de Bolivia MMAyA: Ministerio de Medio Ambiente y Agua POA: Plan Operativo Anual PRASDES: Programa Regional Andino para el Fortalecimiento de los Servicios Meteorológicos, Hidrológicos, Climáticos y el Desarrollo SAT: Sistema de Alerta Temprana SENAMHI: Servicio Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología SIG: Sistema de Información Geográfica TDPS: Sistema Titicaca-Desaguadero-Poopó-Salar de Coipasa UE: Unidad Educativa UGR: Unidad de Gestión de Riesgos VIDECI: Viceministerio de Defensa Civil Presentación Desde noviembre de 2015 el Programa Regional Andino para el Fortalecimiento -

Cartography and the Conception, Conquest and Control of Eastern Africa, 1844-1914

Delineating Dominion: Cartography and the Conception, Conquest and Control of Eastern Africa, 1844-1914 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Robert H. Clemm Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin, Advisor Alan Beyerchen Ousman Kobo Copyright by Robert H Clemm 2012 Abstract This dissertation documents the ways in which cartography was used during the Scramble for Africa to conceptualize, conquer and administer newly-won European colonies. By comparing the actions of two colonial powers, Germany and Britain, this study exposes how cartography was a constant in the colonial process. Using a three-tiered model of “gazes” (Discoverer, Despot, and Developer) maps are analyzed to show both the different purposes they were used for as well as the common appropriative power of the map. In doing so this study traces how cartography facilitated the colonial process of empire building from the beginnings of exploration to the administration of the colonies of German and British East Africa. During the period of exploration maps served to make the territory of Africa, previously unknown, legible to European audiences. Under the gaze of the Despot the map was used to legitimize the conquest of territory and add a permanence to the European colonies. Lastly, maps aided the capitalist development of the colonies as they were harnessed to make the land, and people, “useful.” Of special highlight is the ways in which maps were used in a similar manner by both private and state entities, suggesting a common understanding of the power of the map. -

The Lost Ordnance Survey Two-Inch

Sheetlines The journal of THE CHARLES CLOSE SOCIETY for the Study of Ordnance Survey Maps “Unfinished business: the lost Ordnance Survey two- inch mapping of Scotland, 1819-1828 and 1852” Richard Oliver Sheetlines, 78 (April 2007), pp.9-31 Stable URL: http://www.charlesclosesociety.org/files/Issue78page9.pdf This article is provided for personal, non-commercial use only. Please contact the Society regarding any other use of this work. Published by THE CHARLES CLOSE SOCIETY for the Study of Ordnance Survey Maps www.CharlesCloseSociety.org The Charles Close Society was founded in 1980 to bring together all those with an interest in the maps and history of the Ordnance Survey of Great Britain and its counterparts in the island of Ireland. The Society takes its name from Colonel Sir Charles Arden-Close, OS Director General from 1911 to 1922, and initiator of many of the maps now sought after by collectors. The Society publishes a wide range of books and booklets on historic OS map series and its journal, Sheetlines, is recognised internationally for its specialist articles on Ordnance Survey-related topics. 9 Unfinished business: the lost Ordnance Survey two-inch mapping of Scotland, 1819-1828 and 1852 Richard Oliver An obscure episode, and nothing to show for it It is perhaps understandable that maps that exist and can be seen tend to excite more general interest than those that do not, and that the Charles Close Society receives its support for studying what the Ordnance Survey has produced, rather than what is has not. Therefore the indulgence of at least some readers is craved for this exploration of two of the less-known episodes of OS history. -

Las Relaciones Entre El Perú Y Bolivia (1826-2013)

Fabián Novak Sandra Namihas SERIE: POLÍTICA EXTERIOR PERUANA LAS RELACIONES ENTRE EL PERÚ Y BOLIVIA ( 1826-2013 ) SERIE: POLÍTICA EXTERIOR PERUANA LAS RELACIONES ENTRE EL PERÚ Y BOLIVIA (1826-2013) Serie: Política Exterior Peruana LAS RELACIONES ENTRE EL PERÚ Y BOLIVIA (1826-2013) Fabián Novak Sandra Namihas 2013 Serie: Política Exterior Peruana Las relaciones entre el Perú y Bolivia (1826-2013) Primera edición, octubre de 2013 © Konrad Adenauer Stiftung General Iglesias 630, Lima 18 – Perú Email: [email protected] URL: <www.kas.de/peru> Telf: (51-1) 208-9300 Fax: (51-1) 242-1371 © Instituto de Estudios Internacionales (IDEI) Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú Plaza Francia 1164, Lima 1 – Perú Email: [email protected] URL: <www.pucp.edu.pe/idei> Telf: (51-1) 626-6170 Fax: (51-1) 626-6176 Diseño de cubierta: Eduardo Aguirre / Sandra Namihas Derechos reservados, prohibida la reproducción de este libro por cualquier medio, total o parcialmente, sin permiso expreso de los editores. Hecho el depósito legal en la Biblioteca Nacional del Perú Registro: Nº 2013-14683 ISBN Nº 978-9972-671-18-0 Impreso en: EQUIS EQUIS S.A. RUC: 20117355251 Jr. Inca 130, Lima 34 – Perú Impreso en el Perú – Printed in Peru A la memoria de mi padre y hermano, F.N. A mis padres, Jorge y María Luisa S.N. Índice Introducción …………………………….……...…………….…… 17 CAPÍTULO 1: El inicio de ambas repúblicas y los grandes temas bilaterales en el siglo XIX ……………………….………..……… 19 1 El inicio de las relaciones diplomáticas y el primer intento de federación peruano-boliviana ……………............. 22 2 El comienzo del largo camino para la definición de los límites ……………………………………………...…. -

Bolivia 2006

ERlK MONASTERIO Bolivia 2006 Thanks are due to thejDlfowing contributors to these notes: Lindsay Griffin, John Biggar, Nick Flyvbjerg, Juliette Gehard, Arnaud Guilfaume, Moira Herring, Alain Mesili, Charlie Netherton and Katsutaka Yokoyama. Favourable weather conditions arrived early in the 2006 season with a premature end to the austral summer monsoon. As usual, most climbing activity was on the normal routes on Huayna Potosi, Illimani and Condoriri, but it was gratifying to see more trekking and climbing activity in the northern Cordillera Real, which has been quite neglected in recent years. Glacier conditions on the approaches to the western routes of Ancohuma and Illampu were by far the best seen over the past 10 years, as there were few crevasses and penitents, but the overall trend is still for rapid glacial recession. Unseasonably early snowfall arrived later in the season, substantially increasing the avalanche risk. Local guides say the climbing season is moving earlier each year. In 2005 the weather was almost continuously bad throughout September. The political situation is always important when it comes to planning a trip to Bolivia's Cordillera. The February 2006 democratic elections were unprecedented in terms of voter turnout, and for the first time elected as president an indigenous leader from a non-traditional party. Evo Morales won by a clear majority and formed a government with strong ideological affiliations to Venezuela and Cuba, rejecting US influence. This brought initial stability to the nation and the political demonstrations and strikes that in previous years paralysed the nation were not a problem during the May-September climbing season. -

Coğrafya: Geçmiş-Kavramlar- Coğrafyacilar

COĞRAFYA: GEÇMİŞ-KAVRAMLAR- COĞRAFYACILAR COĞRAFYA LİSANS PROGRAMI DR. ÖĞR. ÜYESİ ATİLLA KARATAŞ İSTANBUL ÜNİVERSİTESİ AÇIK VE UZAKTAN EĞİTİM FAKÜLTESİ Yazar Notu Elinizdeki bu eser, İstanbul Üniversitesi Açık ve Uzaktan Eğitim Fakültesi’nde okutulmak için hazırlanmış bir ders notu niteliğindedir. İSTANBUL ÜNİVERSİTESİ AÇIK VE UZAKTAN EĞİTİM FAKÜLTESİ COĞRAFYA LİSANS PROGRAMI COĞRAFYA: GEÇMİŞ-KAVRAMLAR- COĞRAFYACILAR Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Atilla KARATAŞ ÖNSÖZ İstanbul Üniversitesi Açık ve Uzaktan Eğitim Fakültesi Coğrafya programı kapsamında, Coğrafya: Geçmiş-Kavramlar-Coğrafyacılar dersi için hazırlanmış olan bu notlar, ders içeriğinin daha iyi anlaşılması amacıyla internet üzerinde erişime açık görsellerle zenginleştirilmiş ve “Ders Notu” formunda düzenlenmiştir. Bu sebeple kurallarına uygun olarak yapılmakla birlikte metin içerisindeki alıntılar için ilgili bölümlerde referans verilmemiş, ancak çalışmanın sonundaki “Kaynakça” bölümünde faydalanılan kaynaklara ait bilgiler sıralanmıştır. Bu çalışmaya konu olmuş bütün bilim insanlarını minnet ve şükranla yâd eder, muhtemel eksik ve hatalar için okuyucunun anlayışına muhtaç olduğumuzun ikrarını elzem addederim. Öğrencilerimiz ve Coğrafya bilimine gönül vermiş herkes için faydalı olması ümidiyle… Dr. Öğr. Üyesi Atilla KARATAŞ 20.07.2017 1 İÇİNDEKİLER ÖNSÖZ .............................................................................................................................................. 1 İÇİNDEKİLER ................................................................................................................................. -

Sheetlines the Journal of the CHARLES CLOSE SOCIETY for the Study of Ordnance Survey Maps

Sheetlines The journal of THE CHARLES CLOSE SOCIETY for the Study of Ordnance Survey Maps “Charles Frederick Arden-Close” anon Sheetlines, 2 (December 1981), pp.3-5 Stable URL: http://www.charlesclosesociety.org/files/Issue2page3.pdf This article is provided for personal, non-commercial use only. Please contact the Society regarding any other use of this work. Published by THE CHARLES CLOSE SOCIETY for the Study of Ordnance Survey Maps www.CharlesCloseSociety.org The Charles Close Society was founded in 1980 to bring together all those with an interest in the maps and history of the Ordnance Survey of Great Britain and its counterparts in the island of Ireland. The Society takes its name from Colonel Sir Charles Arden-Close, OS Director General from 1911 to 1922, and initiator of many of the maps now sought after by collectors. The Society publishes a wide range of books and booklets on historic OS map series and its journal, Sheetlines, is recognised internationally for its specialist articles on Ordnance Survey-related topics. [Unsigned Article] CHARLES FREDERICK ARDEN-CLOSE 1865-1952 Colonel Sir Charles Arden-Close died 29 years ago, on 19th December 1952. For many of us today his name is kept alive principally by the republication of his book 'The early years of the Ordnance Survey' 1 of which it has been said that 'in writing these historical and individual notes, Close performed a service to the Ordnance Survey as well as to British geodesy and British surveyors'. In fact the book also provides more of a service to historians than Close could have realised at the time he wrote it. -

Brigadier EM Jack, CB

No. 4273 September 22, 1951 NATURE 495 Born on April 27, 1882, at Wimbledon, Agar pa,ised work of others, Agar played an important part in from his preparatory school to Sedbergh and then substantiating the view that environmental or to King's College, Cambridge, where his tutor w&S 'acquired' characters are not inherited and are S. F. Harmer. He went through the regular courses therefore not available for the process of racial of instruction for the Natural Sciences Tripos, Parts I evolution. and II, in both of which he obtained a first cla,is. In its third phase, Agar's work diverged from the Of all his teachers he looked back with special realm of pure science, in which things are observed, gratitude to Harmer, for his inculcation of precise accurately recorded and when possible seriated into and orderly method, and to Bateson, then in the a general expression, into the realm of 'philosophy', flood tide of Mendelism, for turning his mind in the which deals rather with ide&S or opinions, and is free direction of his future research in genetics. from the constraints to which purely scientific I had been impressed by Agar as the most out research is subject. In this phase Agar was, above all, standing member of the Tripos class in zoology influenced by the philosophy of A. N. Whitehead during my last year as demonstrator ; so when he primarily a mathematician, not a biologist-as had completed his Tripos, I invited him to join the expounded in his "Process and Reality". According staff of the Zoology Department in the University of to this philosophy, reality consists not in substance Glasgow, on which he remained until 1920, holding but in process, and the difference between living and latterly the position of senior lecturer. -

Problemas Juridicos Que Plantea

PONTifiCIA UNIVE.R51UAD CATOLICA DEL PERU TE S 1 S EL APROVECHAMIENTP DE~ LAS .~GUAS DEL LAGO TITICACA Y LOS PROBLEMAS JURIDICOS QUE PLANTEA CARLOS RODRIGUEZ PASTOR MENDOZA LIMA - PERU 1 9 S 8 Ef aprovec~amíento· de (as aguas de( Lago Títícaca y (os prob(emas jurídicos que pían tea Los Gobiernos del Perú y de Bolivia han reconocido formal y s:>lem nemente, por virtud del Convenio suscrito en 1957 para el estudio del apro -vechamiento de las aguas del Lago Titicaca, el "condominio indivisible y exclusivo" que ambos países ejercen sobre ellas. Así las cosas, el presente trabajo encuentra su explicación tanto en la trascendencia jurídica dei problema y en la firme convicción del autor de que la realización de la obra en él tratada tiene insospechados alcances An lo que atañe al desarrollo industrial y al progreso del país, cuanto en la finaHdad práctica de borrar todo rezago de duda, de suspicacia o de vacilación que pudiera quedar en la opinión pública boliviana frente a~ Convenio aludido. Esto último, a raíz de determinada campaña presumible ·mente de buena fe, pero de tinte inocultablemente obstruccionista, llevada a cabo en esa República hermana bajo la invocación de un sentimiento nacio nalista, quizá estrecho y no siempre acertadamente inspirado. Creo que más que un compromiso oficial -ya felizmente logrado urge un acuerdo unánime de los pueblos, único medio de romper las barre _ras del prejuicio y de la indolencia que amenazan negativamente el éxito de la obra. Ni la revolución socio-económica planteada en Bolivia es, por sí sola, suficiente para resolver el grave problema de una masa indígena pauperi zada. -

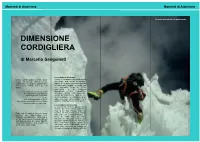

Dimensione Cordigliera

Momenti di Alpinismo Momenti di Alpinismo Scalata sui penitentes di Apolobamba DIMENSIONE CORDIGLIERA di Marcello Sanguineti La cordigliera del silenzio Dedico queste pagine a Yossi Brain, Provate a immaginare un mondo di valli caduto il 25 settembre 1999 sul Nevado dimenticate, una catena di montagne El Presidente (Cordigliera Apolobamba). glaciali che separa il desertico altopiano Il suo sorriso beffardo non è poi così boliviano dalle “yungas”, le umide gole lontano. che degradano verso la foresta amazzonica: è la Cordigliera ...non voglio vincere queste pareti, Apolobamba. Carte topografiche ma aggirarmi fra i loro precipizi incomplete e a volte errate, isolamento e e naufragare nei loro silenzi. scarsa documentazione caratterizzano Lo so, queste montagne, che offrono pareti mai sarà come riprendere un gioco: salite sulle quali aprire eleganti vie di dimenticato nelle pieghe della memoria, ghiaccio: un fantastico terreno di gioco. ma ancora ben vivo nel cuore... La cordigliera Apolobamba E’ una catena montuosa glaciale che si estende per circa ottanta chilometri a nord-est del lago Titicaca, vicino alla Dopo anni di vacanze estive in gruppi frontiera tra Perù e Bolivia; la maggior montuosi che rappresentano mete parte delle vette si trova in Bolivia o nei classiche dell’alpinismo extraeuropeo, pressi del confine fra i due Paesi. nel ’98 ho scelto con Alessandro Bianchi Diversamente dalle mete classiche delle (CAI ULE, Genova) due angoli appartati spedizioni alpinistiche in Sud America, è delle Ande Boliviane. Si è rivelata una poco frequentata e poco conosciuta, scelta davvero azzeccata… nonostante abbia caratteristiche simili a quelle delle cordigliere più famose (ad esempio, la Cordigliera Blanca e la Real). -

The New One-Inch and Quarter-Inch Maps of the Ordnance Survey: Discussion Author(S): Colonel Whitlock, Thomas Holdich, W

The New One-Inch and Quarter-Inch Maps of the Ordnance Survey: Discussion Author(s): Colonel Whitlock, Thomas Holdich, W. J. Johnston, Coote Hedley, Major Mason, Mr. Reynolds, Mr. Hinks, Edward Gleichen and W. Pitt Source: The Geographical Journal, Vol. 55, No. 3 (Mar., 1920), pp. 196-200 Published by: geographicalj Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1781603 Accessed: 28-06-2016 01:27 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Wiley, The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Geographical Journal This content downloaded from 128.197.26.12 on Tue, 28 Jun 2016 01:27:46 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms 196 THE NEW ONE-INCH AND QUARTER-INCH MAPS This year two sheets of the new " Quarter-inch " have been published. This is an entirely new map prepared as follows : (i) The outline, water and contours were drawn on " blues" on the half-inch scale. (2) These were then photographed down to the quarter-inch scale. (3) From the negative a photo-etched copper plate was made of the three drawings?outline, water and contours.