Essays on the Tale of Genji

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Storytelling Practices in the New Millennium a Snake and Dragon Lore Case Study

Storytelling Practices in the New Millennium A Snake and Dragon Lore Case Study MA Thesis Asian Studies (60 ECTS) History, Art and Culture of Asia Martina Ferrara s1880624 Supervisor Professor Ivo Smits December 2017 1 2 Abstract In this new millennium, the world is facing many drastic changes. Technology has revolutionized our lives and we are still trying to grasp the essence of this new age. Many traditions are fading, one of them being the practice of oral storytelling, used in pre modern societies by common folks to amuse themselves and to educate children at the same time. This essay analyzes the transition from traditional storytelling to mass communication, and its implications, through the case study of Japanese snake and dragon lore. The dragon, a well established symbol of Eastern Asian cultures, is the mythical evolution of a snake, considered to belong to the same species. The two animals are treated, however, in very different ways: the first is venerated as a kami, a god, while the second, even though object of worship too, is so feared that speaking about it is still considered a taboo. During the last century oral storytelling practice has been fading out, overpowered by the attractiveness of new medias. However, while the traditional practice is slowly dying out, storytelling itself is, I argue, just changed media. This essay will look into modern portraying of snakes and dragons, comparing tradition with new media. Through the example of Oscar winner movie Spirited Away (2001) and especially through the character of the white dragon Haku, it will be shown how anime and manga can represent a new way for the transmission and preservation of folk tales and beliefs. -

Full Download

VOLUME 1: BORDERS 2018 Published by National Institute of Japanese Literature Tokyo EDITORIAL BOARD Chief Editor IMANISHI Yūichirō Professor Emeritus of the National Institute of Japanese 今西祐一郎 Literature; Representative Researcher Editors KOBAYASHI Kenji Professor at the National Institute of Japanese Literature 小林 健二 SAITō Maori Professor at the National Institute of Japanese Literature 齋藤真麻理 UNNO Keisuke Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese 海野 圭介 Literature KOIDA Tomoko Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese 恋田 知子 Literature Didier DAVIN Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese ディディエ・ダヴァン Literature Kristopher REEVES Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese クリストファー・リーブズ Literature ADVISORY BOARD Jean-Noël ROBERT Professor at Collège de France ジャン=ノエル・ロベール X. Jie YANG Professor at University of Calgary 楊 暁捷 SHIMAZAKI Satoko Associate Professor at University of Southern California 嶋崎 聡子 Michael WATSON Professor at Meiji Gakuin University マイケル・ワトソン ARAKI Hiroshi Professor at International Research Center for Japanese 荒木 浩 Studies Center for Collaborative Research on Pre-modern Texts, National Institute of Japanese Literature (NIJL) National Institutes for the Humanities 10-3 Midori-chō, Tachikawa City, Tokyo 190-0014, Japan Telephone: 81-50-5533-2900 Fax: 81-42-526-8883 e-mail: [email protected] Website: https//www.nijl.ac.jp Copyright 2018 by National Institute of Japanese Literature, all rights reserved. PRINTED IN JAPAN KOMIYAMA PRINTING CO., TOKYO CONTENTS -

Supernatural Elements in No Drama Setsuico

SUPERNATURAL ELEMENTS IN NO DRAMA \ SETSUICO ITO ProQuest Number: 10731611 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731611 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 Supernatural Elements in No Drama Abstract One of the most neglected areas of research in the field of NS drama is its use of supernatural elements, in particular the calling up of the spirit or ghost of a dead person which is found in a large number (more than half) of the No plays at present performed* In these 'spirit plays', the summoning of the spirit is typically done by a travelling priest (the waki)* He meets a local person (the mae-shite) who tells him the story for which the place is famous and then reappears in the second half of the.play.as the main person in the story( the nochi-shite ), now long since dead. This thesis sets out to show something of the circumstances from which this unique form of drama v/as developed. -

The Myth of the Goddess of the Undersea World and the Tale of Empress Jingu’S Subjugation of Silla

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1993 20/2-3 The Myth of the Goddess of the Undersea World and the Tale of Empress Jingu’s Subjugation of Silla Akima Toshio In prewar Japan, the mythical tale of Empress Jingii’s 神功皇后 conquest of the Korean kingdoms comprised an important part of elementary school history education, and was utilized to justify Japan5s coloniza tion of Korea. After the war the same story came to be interpreted by some Japanese historians—most prominently Egami Namio— as proof or the exact opposite, namely, as evidence of a conquest of Japan by a people of nomadic origin who came from Korea. This theory, known as the horse-rider theory, has found more than a few enthusiastic sup porters amone Korean historians and the Japanese reading public, as well as some Western scholars. There are also several Japanese spe cialists in Japanese history and Japan-Korea relations who have been influenced by the theory, although most have not accepted the idea (Egami himself started as a specialist in the history of northeast Asia).1 * The first draft of this essay was written during my fellowship with the International Research Center for Japanese Studies, and was read in a seminar organized by the institu tion on 31 January 199丄. 1 am indebted to all researchers at the center who participated in the seminar for their many valuable suggestions. I would also like to express my gratitude to Umehara Takeshi, the director general of the center, and Nakanism Susumu, also of the center, who made my research there possible. -

Ore Giapponesi: Giorgio Bernari E Adriano Somigli Lia Beretta

COLLANA DI STUDI GIAPPONESI RICErcHE 4 Direttore Matilde Mastrangelo Sapienza Università di Roma Comitato scientifico Giorgio Amitrano Università degli Studi di Napoli “L’Orientale” Gianluca Coci Università di Torino Silvana De Maio Università degli Studi di Napoli “L’Orientale” Chiara Ghidini Fondazione Bruno Kessler Andrea Maurizi Università degli Studi di Milano–Bicocca Maria Teresa Orsi Sapienza Università di Roma Ikuko Sagiyama Università degli Studi di Firenze Virginia Sica Università degli Studi di Milano Comitato di redazione Chiara Ghidini Fondazione Bruno Kessler Luca Milasi Sapienza Università di Roma Stefano Romagnoli Sapienza Università di Rom COLLANA DI STUDI GIAPPONESI RICErcHE La Collana di Studi Giapponesi raccoglie manuali, opere di saggistica e traduzioni con cui diffondere lo studio e la rifles- sione su diversi aspetti della cultura giapponese di ogni epoca. La Collana si articola in quattro Sezioni (Ricerche, Migaku, Il Ponte, Il Canto). I testi presentati all’interno della Collana sono sottoposti a una procedura anonima di referaggio. La Sezione Ricerche raccoglie opere collettanee e monografie di studiosi italiani e stranieri specialisti di ambiti disciplinari che coprono la realtà culturale del Giappone antico, moder- no e contemporaneo. Il rigore scientifico e la fruibilità delle ricerche raccolte nella Sezione rendono i volumi presentati adatti sia per gli specialisti del settore che per un pubblico di lettori più ampio. Variazioni su temi di Fosco Maraini a cura di Andrea Maurizi Bonaventura Ruperti Copyright © MMXIV Aracne editrice int.le S.r.l. www.aracneeditrice.it [email protected] via Quarto Negroni, 15 00040 Ariccia (RM) (06) 93781065 isbn 978-88-548-8008-5 I diritti di traduzione, di memorizzazione elettronica, di riproduzione e di adattamento anche parziale, con qualsiasi mezzo, sono riservati per tutti i Paesi. -

The Symbol of the Dragon and Ways to Shape Cultural Identities in Institute Working Vietnam and Japan Paper Series

2015 - HARVARD-YENCHING THE SYMBOL OF THE DRAGON AND WAYS TO SHAPE CULTURAL IDENTITIES IN INSTITUTE WORKING VIETNAM AND JAPAN PAPER SERIES Nguyen Ngoc Tho | University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Vietnam National University – Ho Chi Minh City THE SYMBOL OF THE DRAGON AND WAYS TO SHAPE 1 CULTURAL IDENTITIES IN VIETNAM AND JAPAN Nguyen Ngoc Tho University of Social Sciences and Humanities Vietnam National University – Ho Chi Minh City Abstract Vietnam, a member of the ASEAN community, and Japan have been sharing Han- Chinese cultural ideology (Confucianism, Mahayana Buddhism etc.) and pre-modern history; therefore, a great number of common values could be found among the diverse differences. As a paddy-rice agricultural state of Southeast Asia, Vietnam has localized Confucianism and absorbed it into Southeast Asian culture. Therefore, Vietnamese Confucianism has been decentralized and horizontalized after being introduced and accepted. Beside the local uniqueness of Shintoism, Japan has shared Confucianism, the Indian-originated Mahayana Buddhism and other East Asian philosophies; therefore, both Confucian and Buddhist philosophies should be wisely laid as a common channel for cultural exchange between Japan and Vietnam. This semiotic research aims to investigate and generalize the symbol of dragons in Vietnam and Japan, looking at their Confucian and Buddhist absorption and separate impacts in each culture, from which the common and different values through the symbolic significances of the dragons are obviously generalized. The comparative study of Vietnamese and Japanese dragons can be enlarged as a study of East Asian dragons and the Southeast Asian legendary naga snake/dragon in a broader sense. The current and future political, economic and cultural exchanges between Japan and Vietnam could be sped up by applying a starting point at these commonalities. -

Panthéon Japonais

Liste des divinités et des héros des légendes et de la mythologie japonaises Divinité Kami (m) Kami (f) Esprit Bouddhisme Monstre Animal Humain Acala Déité bouddhique du mikkyo, maître immuable associé au feu et à la colère; il est l'un des cinq rois du savoir. Agyo-zo Dans le bouddhisme japonais, Agyo-zo et Ungyo-zo se tiennent à la porte des édifices pour les protéger. Aizen myo-o Déité du bouddhisme japonais qui purifie les hommes des désirs terrestres et les libère de l'illusion. Il est représenté en rouge vif (passion), avec trois yeux, six bras et un air irritée, Il tient à la main un arc et des flèches ou un crochet. Ajisukitakahikone ou Aji-Shiki ou Kamo no Omikami Kami de l'agriculture, de la foudre et des serpents. Il créa la montagne Moyama dans la province de Mino en piétinant une maison de deuil parce qu'on l'avait pris pour le défunt. Akashagarbha Un des treize bouddhas de l’école tantrique japonaise Shingon Ama no Fuchigoma Cheval mythique de Susanoo qui est décrit dans le Nihon-Shoki . Ama no Kagaseo Autre nom de Amatsu Mikaboshi le kami du mal Ame no Tajikarao Kami des exercices physiques et de la force brutale qui dégagea l'entrée de la grotte où Amatersu s'était réfugiée. Amakuni Forgeron légendaire qui forgea le tachi, l'épée courbe ancêtre de Takana. Ama no Zako Monstrueuse kami née des vomissures de Susanoo Amaterasu Kami du soleil et reine des Hautes Plaines Célestes Amatsu mikaboshi Kami du mal Ame no Oshido Mimi Fils d'Amaterasu qui refusa d'aller gouverner la terre qu'il trouvait trop pleine de cMhaos. -

Ōwatatsumi , Was the Tutelary Deity of the Sea in Japanese Mythology

Ry ūjin - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ryujin Ry ūjin From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia (Redirected from Ryujin) Ry ūjin or Ry ōjin (龍神 "dragon god" ), also known as Ōwatatsumi , was the tutelary deity of the sea in Japanese mythology. This Japanese dragon symbolized the power of the ocean, had a large mouth, and was able to transform into a human shape. Ry ūjin lived in Ry ūgū-j ō, his palace under the sea built out of red and white coral, from where he controlled the tides with magical tide jewels. Sea turtles, fish and jellyfish are often depicted as Ry ūjin's servants. Ry ūjin was the father of the beautiful goddess Otohime who married the hunter prince Hoori. The first Emperor of Japan, Emperor Jimmu, is said to have been a grandson of Otohime and Hoori's. Thus, Ry ūjin is said to be one of the ancestors of the Japanese imperial dynasty. Contents 1 Alternative legends ū 2 In Shinto Princess Tamatori steals Ry jin's jewel, by Utagawa Kuniyoshi. 3 In popular culture 4 References 5 External links Alternative legends According to legend, the Empress Jing ū was able to carry out her attack into Korea with the help of Ry ūjin's tide jewels. Upon confronting the Korean navy, Jing ū threw the kanju (干珠 "tide-ebbing jewel" ) into the sea, and the tide receded. The Korean fleet was stranded, and the men got out of their ships. Jing ū then threw down the manju (満珠 "tide-flowing jewel" ) and the water rose, drowning the Korean soldiers. -

Download 1 File

Qfacnell UtttDcratty SIthratg Jlll;aca, UStm Snrk CHARLES WILLIAM WASON COLLECTION CHINA AND THE CHINESE THE GIFT OF CHARLES WILLIAM WASON CLASS OF 1876 1918 Digitized by Microsoft® Library Cornell University GR 830 .D7V83 China and Jaoanv Digitized by Microsoft® This book was digitized by Microsoft Corporation in cooperation witli Cornell University Libraries, 2007. You may use and print this copy in limited quantity for your personal purposes, but may not distribute or provide access to it (or modified or partial versions of it) for revenue-generating or other commercial purposes. Digitized by Microsoft® ^\ Cornell University y m Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924021444728 Digitized by Microsoft® Digitized by Microsoft® THE DRAGON IN CHINA AND JAPAN Digitized by Microsoft® Digitized by Microsoft® PREFACE. The student of Chinese and Japanese religion and folklore soon discovers the mighty influence of Indian thought upon the Far-Eastern mind. Buddhism introduced a great number of Indian, not especially Buddhist, conceptions and legends, clad in a Bud- dhist garb, into the eastern countries. In China Taoism was ready to gratefully take up these foreign elements which in many respects resembled its own ideas or were of the same nature; In this way the store of ancient Chinese legends was not only largely enriched, but they were also mixed up with the Indian fables. The same process took place in Japan, when Buddhism, after having conquered Korea, in the sixth century of our era reached Dai Nippon's shores. -

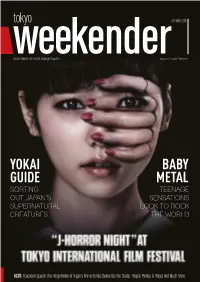

Yokai Guide Baby Metal

OCTOBER 2015 Japan’s number one English language magazine Image © 2015 “Gekijorei” Film Partners YOKAI BABY GUIDE METAL SORTING TEENAGE OUT JAPAN’S SENSATIONS SUPERNATURAL LOOK TO ROCK CREATURES THE WORLD ALSO: Education Special, the Hoop Nation of Nippon, Marie Kondo Cleans Out the Clutter, People, Parties, & Placeswww.tokyoweekender.com and Much MoreOCTOBER 2015 OCTOBER 2015 www.tokyoweekender.com OCTOBER 2015 CONTENTS 15 MASTERS OF J-HORROR The Tokyo International Film Festival brings plenty of screams to the screen © 2015 “Gekijorei” Film Partners 14 16 20 BABYMETAL YOKAI GUIDE EDUCATION SPECIAL Awww...These teenagers are on a rock- Don’t know your kappa from your kirin? Autumn is filled with new developments fueled musical rampage Turn to page 16, dear friends at Tokyo’s international schools 6 The Guide 13 Akita-Style Teppanyaki 34 Previews Our recommendations for hot fall looks, Get ready for some of Japan’s finest The back story of Peter Pan, Keanu takes plus a snack that’s worth a train ride ingredients, artfully prepared at Gomei revenge, and the Not-So-Fantastic Four 8 Gallery Guide 28 Marie Kondo 36 Agenda Edo period adult art, the College Women’s Reclaiming joy by getting rid of clutter? Shimokita Curry Festival, Tokyo Design Association of Japan Print Show, and more Sounds like a win-win Week, and other October happenings 10 Japan Hoops It Up 30 People, Parties, Places 38 Back in the Day Lace ‘em up and get fired up for the A very French soirée, a tasty evening for Looking back at a look ahead to the CWAJ coming season of NBA action Peru, and Bill back in the Studio 54 days Print Show, circa 1974 www.tokyoweekender.com OCTOBER 2015 THIS MONTH IN THE WEEKENDER and domestic for decades, and this year the Tokyo International Film Festival OCTOBER 2015 has decided to take a walk on the spooky side, celebrating the work of three masters of “J-Horror,” including Hideo Nakata, whose upcoming release “Ghost Theater” gets the cover this month. -

141557-Sample.Pdf

Sample file ALP-CS06: Cerulean Seas CCeladoneladon Shores SampleRole Playing Game Supplement file New Undersea “Far East” Guide for use with the Pathfinder® Roleplaying Game* Written by Emily Ember Kubisz, Sam G. Hing, & Cameron Mount ! Credits ! Lead Designer: Emily E. Kubisz Artistic Director & Layout: Tim Adams Authors: Emily Ember Kubisz, Sam G. Hing, & Cameron Mount Editing and Development: Margaret Hawkswood, Patricia Hisakawa & Steven O'Neal Legal Consultant: Marcia McCarthy Cover Artist: Fabio Porfidia; Interior Artists: Tim Adams, Brian Brinlee, Israel Alvarez Carrion, Nicholas Cloister (of www.monstersbyemail.com), Alex Dedy, Thomas Duffy, Hoàng Dũng, Gary Dupuis, Kern Einheit, Mee-Yon Gyeong, Sonya Hallett, Margaret Hawkswood, Pascal Heinzelmann, Ashlee Hynes, Jill Johansen, Bob Kehl, Emily Kubisz, Jakub Kucera, Pauline Melad, Pablo Morales, Matt Morrow, R. J. Palmer, Kathrin Polikeit, Fabio Porfidia, Randall Powell, Sandy Purbacipta, Andreas Rabenstein, Hector Rodriguez, Michael Shears, Stephanie Small, Nirut Tamchoo, Sandara Tang, Andy P. Timm, J. Vahns, John Wigley, Vasilis Zikos Special Thanks to Our Kickstarter Contributors: Adam Windsor, Andrew (ZenDragon), Andrew J. Hayford, Andrew Maizels, Ben Lash, Bill Birchler, Bob Runnicles, Brian Guerrero, Carl Hatfield, Annette B, Chris Kenney, Chris Michael Jahn, Craig Johnston (flash_cxxi), Curtis Edwards, Daniel Craig, Daniel P. Shaefer, Daniyel Mills, Dark Mistress, David Corcoran, Jr., Davin Perry, Dawn Fischer, Dean M. Perez, Douglas Limmer, Douglas Snyder, Ed Courtroul, Ed McLean, Endzeitgeist, Francois Michel, Frank Dyck, Franz Georg Roesel, GLNS, Henry Wong, Herman Duyker, James "Jimbojones" Robertson, James Wood, Jason "Hierax" Verbitsky, Jason "Mikaze" Garrett, Jeremy Wildie, Jon Moore, Joseph "UserClone" Le May, Julien A. 0Féraud, Karen J. Grant, Karl The Good, Kevin Mayz, Kyle Bentley, Lewis Crown, Mark Moreland, Matthew Parker Winn, Michael D. -

Representation of Dinosaurs in 20Th Century Cinema

DARWIN'S DAIKAIJU: REPRESENTATIONS OF DINOSAURS IN 20TH CENTURY CINEMA Nicholas B. Clark A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2018 Committee: Jeremy Wallach, Advisor Esther Clinton Erin Labbie © 2018 Nicholas B. Clark All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jeremy Wallach, Advisor The archetypal dragon, a composite of different living animals, has been popular for centuries, and we still tell stories about it today. One other monster seems to match the dragon in popularity, though it is not among the ranks of the traditional or legendary. Since their discovery in the late 18th century, dinosaurs have been wildly popular in both science and mass culture. The scientific status of dinosaurs as animals has not prevented people from viewing them as monsters, and in some cases, treating these prehistoric reptiles like dragons. This thesis investigates the relationship between the dragon and the dinosaur and the interplay between dragon iconography and dinosaur imagery in five dinosaur monster films from the mid-20th century: The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953), Gojira (1954), Godzilla Raids Again (1955), Gorgo (1961), and Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster (1964). In addressing the arguments other critics have made against equating the dragon with the dinosaur, I will show that the two monstrous categories are treated as similar entities in specific instances, such as in monster- slaying narratives. The five films analyzed in this thesis are monster-slaying narratives that use the dinosaur in place of the dragon, thus “draconifying” the dinosaur.