The Mental Factors Involved in the Practice of Mindfulness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

18 Phases Or Realms

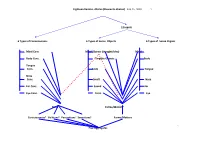

Eighteen Realms- dhatus (Elements-dhatus) Feb.16, 2020 1. 12 inputs 6 Types of Consciousness 6 Types of Sense Objects 6 Types of Sense Organs Mind Cons. Mind Objects (thought/idea) Mind Body Cons. Tangible Objects Body Tongue Cons. Taste Tongue Nose Cons. Smell Nose Ear Cons. Sound Ear Eye Cons. Form Eye Mind Forms/Matters1 Consciousness5 Volitions4 Perceptions3 Sensations2 Forms/Matters . Five Aggregates P2. 1. Rupa: Form or (Matter) Aggregate: the Four Great Elements: 1) Solidity, 2) Fluidity, 3) Heat, 4) Wind/Motion which include the five physical sense-organs i.e. the faculties of the eye, ear, nose, tongue, body besides the brain/mind (note: the brain is an organ, not the mind which is an abstract noun). These sense organs are in contact with the external objects of visible form, sound, odor, taste and tangible things and the mind faculty which corresponds to the intangible objects such as thoughts, ideas, and conceptions. 2. Vedana: Sensations- Feelings (generated by the 6 sense organs eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, brain/mind) 3. Samjna: Perception (Conception): The mental function of shape, color, length, pain, pleasure, un-pleasure, neutral. 4. Samskara: Volition-Mental formation: i.e. flashback, will, intention, or the mental function that accounts for craving. 5. Vijnana : Consciousness( Cognition, discrimination-Mano consciousness): the respective consciousness arises when 6 sense organs eye , ear, nose, tongue, body, brain/mind are in contact with the 6 sense objects form , sound, smell, taste, tangible objects , and mental objects. Please be note that Vijnana Consciousness can be further classified into the 6th, 7th and the 8th according to the Vijhanavada (Mere-Mind) School: Mano Consciousness (6th Consciousness): The front 5 senses report to and co-ordinate by the 6th senses in reaction to the 6 sense objects, gather sense data, discriminate, recall it’s the active, coarse and manifest portion of the Manas Vijnanna. -

Lankavatara-Sutra.Pdf

Table of Contents Other works by Red Pine Title Page Preface CHAPTER ONE: - KING RAVANA’S REQUEST CHAPTER TWO: - MAHAMATI’S QUESTIONS I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XIII XIV XV XVI XVII XVIII XIX XX XXI XXII XXIII XXIV XXV XXVI XXVII XXVIII XXIX XXX XXXI XXXII XXXIII XXXIV XXXV XXXVI XXXVII XXXVIII XXXIX XL XLI XLII XLIII XLIV XLV XLVI XLVII XLVIII XLIX L LI LII LIII LIV LV LVI CHAPTER THREE: - MORE QUESTIONS LVII LVII LIX LX LXI LXII LXII LXIV LXV LXVI LXVII LXVIII LXIX LXX LXXI LXXII LXXIII LXXIVIV LXXV LXXVI LXXVII LXXVIII LXXIX CHAPTER FOUR: - FINAL QUESTIONS LXXX LXXXI LXXXII LXXXIII LXXXIV LXXXV LXXXVI LXXXVII LXXXVIII LXXXIX XC LANKAVATARA MANTRA GLOSSARY BIBLIOGRAPHY Copyright Page Other works by Red Pine The Diamond Sutra The Heart Sutra The Platform Sutra In Such Hard Times: The Poetry of Wei Ying-wu Lao-tzu’s Taoteching The Collected Songs of Cold Mountain The Zen Works of Stonehouse: Poems and Talks of a 14th-Century Hermit The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma P’u Ming’s Oxherding Pictures & Verses TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE Zen traces its genesis to one day around 400 B.C. when the Buddha held up a flower and a monk named Kashyapa smiled. From that day on, this simplest yet most profound of teachings was handed down from one generation to the next. At least this is the story that was first recorded a thousand years later, but in China, not in India. Apparently Zen was too simple to be noticed in the land of its origin, where it remained an invisible teaching. -

Some Reflections on the Place of Philosophy in the Study of Buddhism 145

Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies ^-*/^z ' '.. ' ' ->"•""'",g^ x Volume 18 • Number 2 • Winter 1995 ^ %\ \l '»!#;&' $ ?j On Method \>. :''i.m^--l'-' - -'/ ' x:N'' ••• '; •/ D. SEYFORT RUEGG £>~C~ ~«0 . c/g Some Reflections on the Place of Philosophy in the Study of Buddhism 145 LUIS O. G6MEZ Unspoken Paradigms: Meanderings through the Metaphors of a Field 183 JOSE IGNACIO CABEZ6N Buddhist Studies as a Discipline and the Role of Theory 231 TOM TILLEMANS Remarks on Philology 269 C. W. HUNTINGTON, JR. A Way of Reading 279 JAMIE HUBBARD Upping the Ante: [email protected] 309 D. SEYFORT RUEGG Some Reflections on the Place of Philosophy in the Study of Buddhism I It is surely no exaggeration to say that philosophical thinking constitutes a major component in Buddhism. To say this is of course not to claim that Buddhism is reducible to any single philosophy in some more or less restrictive sense but, rather, to say that what can be meaningfully described as philosophical thinking comprises a major part of its proce dures and intentionality, and also that due attention to this dimension is heuristically necessary in the study of Buddhism. If this proposition were to be regarded as problematic, the difficulty would seem to be due to certain assumptions and prejudgements which it may be worthwhile to consider here. In the first place, even though the philosophical component in Bud dhism has been recognized by many investigators since the inception of Buddhist studies as a modern scholarly discipline more than a century and a half ago, it has to be acknowledged that the main stream of these studies has, nevertheless, quite often paid little attention to the philosoph ical. -

A Buddhist Inspiration for a Contemporary Psychotherapy

1 A BUDDHIST INSPIRATION FOR A CONTEMPORARY PSYCHOTHERAPY Gay Watson Thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the School of Oriental & African Studies, University of London. 1996 ProQuest Number: 10731695 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731695 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT It is almost exactly one hundred years since the popular and not merely academic dissemination of Buddhism in the West began. During this time a dialogue has grown up between Buddhism and the Western discipline of psychotherapy. It is the contention of this work that Buddhist philosophy and praxis have much to offer a contemporary psychotherapy. Firstly, in general, for its long history of the experiential exploration of mind and for the practices of cultivation based thereon, and secondly, more specifically, for the relevance and resonance of specific Buddhist doctrines to contemporary problematics. Thus, this work attempts, on the basis of a three-way conversation between Buddhism, psychotherapy and various themes from contemporary discourse, to suggest a psychotherapy that may be helpful and relevant to the current horizons of thought and contemporary psychopathologies which are substantially different from those prevalent at the time of psychotherapy's early years. -

The Selfless Mind: Personality, Consciousness and Nirvāṇa In

PEI~SONALITY, CONSCIOUSNESS ANI) NII:tVANA IN EAI:tLY BUI)l)HISM PETER HARVEY THE SELFLESS MIND Personality, Consciousness and Nirv3J}.a in Early Buddhism Peter Harvey ~~ ~~~~!;"~~~~urzon LONDON AND NEW YORK First published in 1995 by Curzon Press Reprinted 2004 By RoutledgeCurzon 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Transferred to Digital Printing 2004 RoutledgeCurzon is an imprint ofthe Taylor & Francis Group © 1995 Peter Harvey Typeset in Times by Florencetype Ltd, Stoodleigh, Devon Printed and bound in Great Britain by Biddies Ltd, King's Lynn, Norfolk AU rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any fonn or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any infonnation storage or retrieval system, without pennission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress in Publication Data A catalog record for this book has been requested ISBN 0 7007 0337 3 (hbk) ISBN 0 7007 0338 I (pbk) Ye dhammd hetuppabhavti tesaf{l hetUf{l tathiigato aha Tesaii ca yo norodho evQf{lvtidi mahiisamaf10 ti (Vin.l.40) Those basic processes which proceed from a cause, Of these the tathiigata has told the cause, And that which is their stopping - The great wandering ascetic has such a teaching ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr Karel Werner, of Durham University (retired), for his encouragement and help in bringing this work to publication. I would also like to thank my wife Anne for her patience while I was undertaking the research on which this work is based. -

The Seventy-Five Dharmas (Elements of Existence) in the Abhidharmakosa of Vasubandhu

The Seventy-Five Dharmas (Elements of Existence) in the Abhidharmakosa of Vasubandhu Created Elements, Samskrta-dharma (Dharmas 1-72) I. Forms, Rupani Sense Organs 1. eye, caksu 2. ear, srotra 3. nose, ghrana 4. tongue, jihva 5. body, kaya Sense Objects 6. form, rupa 7. sound, sabda 8. smell, gandha 9. taste. rasa 10. touch, sprastavya 11. element with no manifestation, avijnapti-rupa II. Mind, Citta 12. Mind, Citta III. Concomitant Mental Faculties, Caitasika or Citta-samprayukta-samskara A. General Functions, Mahabhumika 13. feeling, sensation, vedana 14. conception, idea, samjna 15. will, volition, cetana 16. touch, contact, sparsa 17. wish, chanda 18. intellect, mati 19. mindfulness, smrti 20. attention, manaskara 21. decision, abhimoksa 22. concentration, samadhi B. General Functions of Good, Kusala-mahabhumika 23. faith, sraddha 24. energy, effort, virya 25. equanimity, upeksa 26. self respect, shame, hri 27. decorum, apatrapya 28. non-greediness, alobha 29. non-ill-will, advesa 30. non-violence, non-harm, ahimsa 31. confidence, prasrabdhi 32. exertion, apramada C. General Functions of Defilement, Klesa mahabhumika 33. ignorance, moha 34. idleness, non-diligence, pramada 35. indolence, idleness vs. virya, kausidya 36. non-belief, asraddhya 37. low-mindedness, torpor, styana 38. high-mindedness, restlessness, dissipation, auddhatya D. General Functions of Evil, Akusala-mahabhumika 39. lack of self-respect, shamelessness, ahrikya 40. lack of decorum, anapatrapya E. Minor Functions of Defilement, Upaklesa-bhumika 41. anger, krodha 42. concealment, hypocrisy, mraksa 43. parsimony, matsarya 44. jealousy, envy, irsya 45. affliction, pradasa 46. violence, harm, vihimsa 47. enmity, breaking friend, upanaha 48. deceit, maya 49. fraudulence, perfidy, sathya 50. arrogance, mada F. -

1969 01 Jan Vol 16

SOKEI-AN SAYS thing. It is like electricity. No one of the mind and drive out all the the faces of cats and dogs, sometimes TOE FIVE SKANDHAS knows what it is in itself.When elec- things that are smoldering in the the shapes of letters or characters, The five groups of aggregates of tricity relies on something, it burns mind. Just as when a room becomes the forms of bodies,and so forth. all existing dharmas called the five that on which it relies and produces full of cigarette smoke, you open the Vedana- skandha is usually trans- skandhas are the basis for one of the light. When the human soul is in its windows and turn on the electric fan lated by Western scholars as sense- important doctrines in Buddhism. original state, it is called asam- to drive out the smoke, so with medi- perception. It includes feelings- - European and American scholars skrita. When it relies upon something- - tation you must drive out all suffer- pleasant and painful, agreeable and who talk about Buddhism pay little as when electricity relies on some- ing and questions, and keep your mind disagreeable, hunger, itching, and so attention to the five skandhas. Some thing, carbon, iron, or copper wire--i t pure. With this pure mind you will forth. All these belong to vedana. schol ar s who call themselves profound acts differently. It is then said to find your mind's origin. Beauty and ugliness may be included Buddhists have never spoken of this be in the state of samskrita. -

Anapanasati Sutta Student Notes April 2011

Anapanasati Sutta – Student Notes – 1 Anapanasati Sutta Student Notes: Session One 1. “Anapana” means “in-breath and out-breath” “Sati” means “mindfulness” or present moment awareness that simply notices what is happening without in any way interfering, without adding or subtracting anything to or from the experience. It’s bare awareness. So, anapanasati means “mindfulness while breathing in and out”. 2. Background to the sutta: It’s the end of the rainy-season retreat, and the Buddha is so pleased with the meditation practice of those gathered with him, that he announces he is going to stay on another month, the month of the white water-lily or white lotus moon. At the end of that month he gives this teaching on anapanasati, giving the teaching under the full moon at night. The Buddha says: “Mindfulness of in-and-out breathing, when developed and pursued, is of great benefit. Mindfulness of in-and-out breathing, when developed and pursued, brings the four foundations of mindfulness to perfection. The four foundations of mindfulness, when developed and pursued, bring the seven factors of awakening to their culmination. The seven factors of awakening, when developed and pursued, perfect clear insight and liberation.” In other words, anapanasati can lead to enlightenment. Four foundations of mindfulness (satipatthana) are: • Kaya (Body) • Vedana (Feelings or experiencing sensations as pleasant, unpleasant or neutral) • Citta (Mind or mental formations, thoughts and emotions) • Dhammas (mental objects, or perspectives on experience used to investigate reality) These four categories correspond to the four sets of contemplations in the anapanasati method. Seven factors of awakening are a spiral path of conditionality, leading towards enlightenment: 1. -

Buddhism and Vedanta

BUDDHISM AND VEDANTA CHAPTER I RELIGIOUS SITUATION IN INDIA BEFORE BUDDHA'S TIME When one compares the two systems, Buddhism and Ved anta, one is so struck by their similarity that one is tempted to ask if they are not one and the same thing. Buddha, it will be recalled, did not claim that he was preaching anything new. He said he was preaching the ancient way. the Aryan Path, the eternal Dharma. Somehow or other, people had lost sight of this path. They had got caught in the meshes of sacerdotalism. They did all kinds of crazy things thinking they would get whatever they wanted through them, We get a true picture of the situa tion in Lalita vistaral which says : 'Stupid men seek to purify their persons by diverse modes of austerity and penance, and inculcate the same. Some of them cannot make out their mantras; some lick their hands; some are uncleanly; some have no mantras; some wander after different sources; some adore cows, deer, horses, hogs, monkeys ()( elep hants. Some attempt to accomplish their penance by gazing at the sun ... '" ......... resting on one foot or with an arm per- petually uplifted or moving about the knees ... ... ... .. .' Vedanta, with its literature mostly in Sanskrit, was a closed book to the common people. What Buddha taught was essentially this Vedanta, only he taught it in more practical terms, in terms that people would understand, in terms, independent of dogmas, priesthood and sacrament. He presented it in a new garb, stripped of vague phrases, laying the greatest stress on reason and experience. -

Dhanakosa Online Lite Spring Rain on Still Waters – Reflecting on the Five Skandhas Sat 13Th – Thur 18Th March 2021 Led by Nayaka and Moksadhi

Dhanakosa Online Lite Spring rain on still waters – reflecting on the five skandhas Sat 13th – Thur 18th March 2021 Led by Nayaka and Moksadhi About the retreat This is a low time commitment online retreat from Dhanakosa to help us discover how we can use the five skandhas as a reflection scheme in everyday life. It will take a practical and accessible look at this traditional list, reflection on which is said to lead to awakening. The Five Skandhas (rupa/form, vedana/feeling tone, samjna/perception, samskara/”volition” and Vijnana/ consciousness) are a traditional way of breaking down experience and it is said to include the whole of that experience; the whole “person”. It appears in the Pali Canon right back at the first turning of the wheel of the dharma. It is also a central theme in the Heart Sutra and is found in Vajrayana and esoteric Buddhism. Yet, its presentation is often somewhat inaccessible. Nayaka has spent many years exploring how this scheme can be used both in meditation and in daily life reflection in ways that not only enriches our Dharma practice, but our lives generally. This retreat is for regular meditators who have some regular contact with the triratna Buddhist community. Basic familiarity with Buddhist principals and practice, as well as experience of meditation will be assumed. What can you expect from the programme? The retreat will have two sessions a day: • 10 – 11.30am for a short presentation on the days topic and a lead reflection, and then; • 7.30-8.45pm in which we will explore the days topic together and have the opportunity to meditate as a retreat group. -

Tibetan Buddhism and the Formation of Ecological Consciousness: a View from Buryatia

SHS Web of Conferences 55, 05004 (2018) https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/20185505004 ICPSE 2018 Tibetan Buddhism and the formation of ecological consciousness: a view from Buryatia K. Bagaeva1,*, D. Tsyrendorzhieva1, O. Balchindorzhieva1, and M. Badmaeva1. 1Buryat State University, 670000, 24a Smolin str., Ulan-Ude, Russia Abstract. Technicization of human and society, active development of technogenic civilization leads to gradual separation from moral values and principles. These values include ideas of unity and harmony of human with nature, with the surrounding environment, and reasonable, moderate attitude towards natural resources. We believe that humanity should move from the industrial to ecological civilization. The foundations of a new ecophilosophy should become holistic principles, representations of philosophy in general and Buddhism in particular. We outlined basic principles and methods for improving personality of altruistic ethics of Mahayana Buddhism that contribute to human understanding of inseparability, interconnection with the world. We focus on the central Buddhist concept – the absence of an individual ‘I’ that is understood as necessity of recognizing oneself as a separate empirical individual. That is confirmed by a translation of the text PrajnaParamitaHridaya Sutra from Tibetan language. The paper analyzes three types of spiritual personality that correspond to three stages of the Path to awakening. Each stage is a step towards the formation of subjectless consciousness, that is, awareness of universal dependence and responsibility for their actions. The paper argues that for ecological consciousness it is important to form an understanding that the main reason for human existence in not the technosphere, not the economy, but the living nature. 1 Introduction The paper proposes to consider principles of formation of ecological consciousness on the basis of Buddhist philosophy. -

A Comparative Study Between Yoga and Indian Buddhism

《禪與人類文明研究》第三期(2018) International Journal for the Study of Chan Buddhism and Human Civilization Issue 3 (2018), 107–123 A Comparative Study Between Yoga and Indian Buddhism Li Jianxin Abstract There is an intimate relationship between the concepts of samadhi and dhyana in both traditions that demonstrates a parallelism, if not an identity, between the two systems. The foundation for this assertion is a range of common terminology and common descriptions of meditative states seen as the foundation of meditation practice in both traditions. Most notable in this context is the relationship between the samprajnata samadhi states of Classical Yoga and the system of four Buddhist dhyana states (Pali jhana). This is further complicated by the attempt to reconcile this comparison with the development of the Buddhist the arupya-dhyanas, or the series of “formless meditations,” found in Indian Buddhist explications of meditation. This issue becomes even more relevant as we turn toward the conception of nirodha found in both the context of Classical Yoga and in the Buddhist systems, where the relationship between yoga and soteriology becomes an important issue. In particular, we will examine notions of nirodhasamapatti found in Buddhism and the relationship of this state to the identification in Yoga of cittavrttinirodha with kaivalya. Keywords: Yoga, Indian Buddhism, samadhi, dhyanas Li Jianxin is Professor of Institute of World Religions of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. 108 Li Jianxin I. Introduction This paper centers on the comparative research between the Patanjali’s Classical Yoga and the early Buddhism. More specifically, the focus of this study is on the structural comparison between Samadhis in the Classical Yoga and Dhyanas in the early Buddhism.