1969 01 Jan Vol 16

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

\(Cont'd-020310-Heart Sutra Transcribing\)

The Heart of Perfect Wisdom— Lecture on The Heart of Prajñā Pāramitā Sutra (part 2) Transcribed and edited from a talk given by Ven. Jian-Hu on March 10, 2002 at Buddha Gate Monastery ©2002 Buddha Gate Monastery•For Free Distribution Only Translation of Sanskrit Words When Buddhism came to China about two thousand years ago, the Indian Buddhist masters cooperated with the Chinese masters and set up some rules on translation. They were meticulous about the translation process. One of the rules is that if the word has multiple meanings then it should not be translated because if we translate it one way we lose its other meanings. Another rule is that if the Sanskrit word doesn’t have a corresponding concept in Chinese, then it is not translated. Prajñā, nirvana, and skandha are Sanskrit words. Skandha has multiple meanings. There is no corresponding word to explain prajñā or nirvana either in Chinese, or in English. Does anyone know what nirvana is? Well, some 6th grader knows! Last week when I was invited to an intermediate school to introduce Buddhism, I asked, “What is nirvana?” One child said, “I know, it’s a rock band!” Another child raised his hand and said, “nirvana is ultimate peace.” I was really surprised. That is a really good way to describe nirvana – ultimate peace. The Five Skandhas Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara, while deeply immersed in prajñā pāramitā, clearly perceived the empty nature of the five skandhas, and transcended all suffering. Skandha is a Sanskrit word and it means aggregate. Aggregate is an assembly of things. -

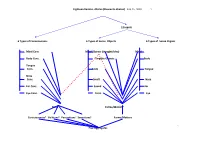

18 Phases Or Realms

Eighteen Realms- dhatus (Elements-dhatus) Feb.16, 2020 1. 12 inputs 6 Types of Consciousness 6 Types of Sense Objects 6 Types of Sense Organs Mind Cons. Mind Objects (thought/idea) Mind Body Cons. Tangible Objects Body Tongue Cons. Taste Tongue Nose Cons. Smell Nose Ear Cons. Sound Ear Eye Cons. Form Eye Mind Forms/Matters1 Consciousness5 Volitions4 Perceptions3 Sensations2 Forms/Matters . Five Aggregates P2. 1. Rupa: Form or (Matter) Aggregate: the Four Great Elements: 1) Solidity, 2) Fluidity, 3) Heat, 4) Wind/Motion which include the five physical sense-organs i.e. the faculties of the eye, ear, nose, tongue, body besides the brain/mind (note: the brain is an organ, not the mind which is an abstract noun). These sense organs are in contact with the external objects of visible form, sound, odor, taste and tangible things and the mind faculty which corresponds to the intangible objects such as thoughts, ideas, and conceptions. 2. Vedana: Sensations- Feelings (generated by the 6 sense organs eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, brain/mind) 3. Samjna: Perception (Conception): The mental function of shape, color, length, pain, pleasure, un-pleasure, neutral. 4. Samskara: Volition-Mental formation: i.e. flashback, will, intention, or the mental function that accounts for craving. 5. Vijnana : Consciousness( Cognition, discrimination-Mano consciousness): the respective consciousness arises when 6 sense organs eye , ear, nose, tongue, body, brain/mind are in contact with the 6 sense objects form , sound, smell, taste, tangible objects , and mental objects. Please be note that Vijnana Consciousness can be further classified into the 6th, 7th and the 8th according to the Vijhanavada (Mere-Mind) School: Mano Consciousness (6th Consciousness): The front 5 senses report to and co-ordinate by the 6th senses in reaction to the 6 sense objects, gather sense data, discriminate, recall it’s the active, coarse and manifest portion of the Manas Vijnanna. -

Lankavatara-Sutra.Pdf

Table of Contents Other works by Red Pine Title Page Preface CHAPTER ONE: - KING RAVANA’S REQUEST CHAPTER TWO: - MAHAMATI’S QUESTIONS I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XIII XIV XV XVI XVII XVIII XIX XX XXI XXII XXIII XXIV XXV XXVI XXVII XXVIII XXIX XXX XXXI XXXII XXXIII XXXIV XXXV XXXVI XXXVII XXXVIII XXXIX XL XLI XLII XLIII XLIV XLV XLVI XLVII XLVIII XLIX L LI LII LIII LIV LV LVI CHAPTER THREE: - MORE QUESTIONS LVII LVII LIX LX LXI LXII LXII LXIV LXV LXVI LXVII LXVIII LXIX LXX LXXI LXXII LXXIII LXXIVIV LXXV LXXVI LXXVII LXXVIII LXXIX CHAPTER FOUR: - FINAL QUESTIONS LXXX LXXXI LXXXII LXXXIII LXXXIV LXXXV LXXXVI LXXXVII LXXXVIII LXXXIX XC LANKAVATARA MANTRA GLOSSARY BIBLIOGRAPHY Copyright Page Other works by Red Pine The Diamond Sutra The Heart Sutra The Platform Sutra In Such Hard Times: The Poetry of Wei Ying-wu Lao-tzu’s Taoteching The Collected Songs of Cold Mountain The Zen Works of Stonehouse: Poems and Talks of a 14th-Century Hermit The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma P’u Ming’s Oxherding Pictures & Verses TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE Zen traces its genesis to one day around 400 B.C. when the Buddha held up a flower and a monk named Kashyapa smiled. From that day on, this simplest yet most profound of teachings was handed down from one generation to the next. At least this is the story that was first recorded a thousand years later, but in China, not in India. Apparently Zen was too simple to be noticed in the land of its origin, where it remained an invisible teaching. -

Buddhist Psychology

CHAPTER 1 Buddhist Psychology Andrew Olendzki THEORY AND PRACTICE ince the subject of Buddhist psychology is largely an artificial construction, Smixing as it does a product of ancient India with a Western movement hardly a century and a half old, it might be helpful to say how these terms are being used here. If we were to take the term psychology literally as referring to “the study of the psyche,” and if “psyche” is understood in its earliest sense of “soul,” then it would seem strange indeed to unite this enterprise with a tradition that is per- haps best known for its challenge to the very notion of a soul. But most dictio- naries offer a parallel definition of psychology, “the science of mind and behavior,” and this is a subject to which Buddhist thought can make a significant contribution. It is, after all, a universal subject, and I think many of the methods employed by the introspective traditions of ancient India for the investigation of mind and behavior would qualify as scientific. So my intention in using the label Buddhist Psychology is to bring some of the insights, observations, and experi- ence from the Buddhist tradition to bear on the human body, mind, emotions, and behavior patterns as we tend to view them today. In doing so we are going to find a fair amount of convergence with modern psychology, but also some intriguing diversity. The Buddhist tradition itself, of course, is vast and has many layers to it. Al- though there are some doctrines that can be considered universal to all Buddhist schools,1 there are such significant shifts in the use of language and in back- ground assumptions that it is usually helpful to speak from one particular per- spective at a time. -

Some Reflections on the Place of Philosophy in the Study of Buddhism 145

Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies ^-*/^z ' '.. ' ' ->"•""'",g^ x Volume 18 • Number 2 • Winter 1995 ^ %\ \l '»!#;&' $ ?j On Method \>. :''i.m^--l'-' - -'/ ' x:N'' ••• '; •/ D. SEYFORT RUEGG £>~C~ ~«0 . c/g Some Reflections on the Place of Philosophy in the Study of Buddhism 145 LUIS O. G6MEZ Unspoken Paradigms: Meanderings through the Metaphors of a Field 183 JOSE IGNACIO CABEZ6N Buddhist Studies as a Discipline and the Role of Theory 231 TOM TILLEMANS Remarks on Philology 269 C. W. HUNTINGTON, JR. A Way of Reading 279 JAMIE HUBBARD Upping the Ante: [email protected] 309 D. SEYFORT RUEGG Some Reflections on the Place of Philosophy in the Study of Buddhism I It is surely no exaggeration to say that philosophical thinking constitutes a major component in Buddhism. To say this is of course not to claim that Buddhism is reducible to any single philosophy in some more or less restrictive sense but, rather, to say that what can be meaningfully described as philosophical thinking comprises a major part of its proce dures and intentionality, and also that due attention to this dimension is heuristically necessary in the study of Buddhism. If this proposition were to be regarded as problematic, the difficulty would seem to be due to certain assumptions and prejudgements which it may be worthwhile to consider here. In the first place, even though the philosophical component in Bud dhism has been recognized by many investigators since the inception of Buddhist studies as a modern scholarly discipline more than a century and a half ago, it has to be acknowledged that the main stream of these studies has, nevertheless, quite often paid little attention to the philosoph ical. -

Pain and Flourishing in Mahayana Buddhist Moral Thought

SOPHIA DOI 10.1007/s11841-017-0619-4 A Nirvana that Is Burning in Hell: Pain and Flourishing in Mahayana Buddhist Moral Thought Stephen E. Harris1 # The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract This essay analyzes the provocative image of the bodhisattva, the saint of the Indian Mahayana Buddhist tradition, descending into the hell realms to work for the benefit of its denizens. Inspired in part by recent attempts to naturalize Buddhist ethics, I argue that taking this ‘mythological’ image seriously, as expressing philosophical insights, helps us better understand the shape of Mahayana value theory. In particular, it expresses a controversial philosophical thesis: the claim that no amount of physical pain can disrupt the flourishing of a fully virtuous person. I reconstruct two related elements of early Buddhist psychology that help us understand this Mahayana position: the distinction between hedonic sensation (vedanā) and virtuous or nonvirtous mental states (kuśala/akuśala-dharma); and the claim that humans are massively deluded as to what constitutes well-being. Doing so also lets me emphasize the continuity between early Buddhist and Mahayana traditions in their views on well-being and flourishing. Keywords Mahayana Buddhism . Buddhist ethics . Buddhism . Ethics . Hell Julia Annas has shown that taking seriously Stoic and Epicurean claims that the sage is happy even while being tortured on the rack helps articulate the structure of their ethics, and in particular the relationship between virtue (arête) and happiness (eudaimonia).1 In this essay, I apply this strategy to Mahayana Buddhist moral philosophy by taking seriously the image of the bodhisattva joyfully diving into the hell realms. -

A Buddhist Inspiration for a Contemporary Psychotherapy

1 A BUDDHIST INSPIRATION FOR A CONTEMPORARY PSYCHOTHERAPY Gay Watson Thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the School of Oriental & African Studies, University of London. 1996 ProQuest Number: 10731695 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731695 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT It is almost exactly one hundred years since the popular and not merely academic dissemination of Buddhism in the West began. During this time a dialogue has grown up between Buddhism and the Western discipline of psychotherapy. It is the contention of this work that Buddhist philosophy and praxis have much to offer a contemporary psychotherapy. Firstly, in general, for its long history of the experiential exploration of mind and for the practices of cultivation based thereon, and secondly, more specifically, for the relevance and resonance of specific Buddhist doctrines to contemporary problematics. Thus, this work attempts, on the basis of a three-way conversation between Buddhism, psychotherapy and various themes from contemporary discourse, to suggest a psychotherapy that may be helpful and relevant to the current horizons of thought and contemporary psychopathologies which are substantially different from those prevalent at the time of psychotherapy's early years. -

The Buddhist Perspective on Human Fulfillment: the Pure Land by Alfred Bloom, Emeritus Professor, University of Hawaii

The Buddhist Perspective on Human Fulfillment: The Pure Land by Alfred Bloom, Emeritus Professor, University of Hawaii Every major religion of salvation has a vision of paradise, the destination of the faithful. In the early tradition of Buddhism the goal was inconceivable Nirvana. Nirvana as a term meant to blow out, that is, blowing out or extinction of the winds of passions, delusion and greed; transcendence of karma. It was not a place to go, but more a state of being or condition beyond description or conception. The Buddha, upon his enlightenment, attained partial Nirvana because he willed to stay in the world to share his teaching. However, he was beyond karma and transmigration based on good deeds. Though the Buddha voluntarily remained in the world, he was not of the world, stained by its impurities. When he died, Buddha attained perfect or complete Nirvana and was beyond conceptions such as being or non-being. He was totally released from all the passions, discriminations and attachments that mark life in this world. Yet he was not in a “place.” This understanding also goes back to the Buddhist view that there is no abiding essence in things or what we would call a soul. Rather, beings are temporary configurations of elements called skandha. The skandha which are bound by karma disperse when the karmic bonds are broken, and in the case of the Buddha, purified of all karmic taint. In early Buddhist art, the Buddha was represented by an empty chair, indicating that he is indefinable in the nirvanic state. This conception of Buddha’s destiny is naturally difficult to understand and has been a problem to convey to the general public through the centuries. -

Tantric Exposition of the Dependent Origination According to the Caṇḍamahāroṣaṇatantra, Chapter XVI: Pratītyasamutpāda-Paṭala

ROCZNIK ORIENTALISTYCZNY, T. LXV, Z. 1, 2012, (s. 140–148) MAREK MEJOR Tantric Exposition of the Dependent Origination according to the Caṇḍamahāroṣaṇatantra, Chapter XVI: pratītyasamutpāda-paṭala Abstract The Caṇḍamahāroṣaṇatantra, or “Tantra of Fierce and Greatly Wrathful One”, belongs to the class of Highest Tantras (anuttarayoga, rnal ’byor chen po bla med). The text which has been preserved in the Sanskrit original and in Tibetan translation consists of twenty five chapters (paṭala). The 16th chapter entitled pratītyasamutpāda-paṭala is an exposition of the doctrine of dependent origination. The present author is preparing a critical edition of this chapter from Sanskrit and Tibetan, provided with an annotated translation. In this paper is offered a working translation alone with occasional references the readings of the oldest Sanskrit palm leaf manuscripts, compared with the Tibetan translation (Wanli edition). Keywords: Buddhism, Tantra, doctrine of causality, Sanskrit manuscripts, Tibetan Kanjur 1. The Caṇḍamahāroṣaṇatantra (henceforth abbreviated CMT), or “Tantra of Fierce and Greatly Wrathful One”, belongs to the class of Highest Tantras (anuttarayoga, rnal ’byor chen po bla med).1 According to the fourfold classification in Bu ston’s Catalogue of Tantras (Rgyud ʼbum gyi dkar chag), CMT is farther classified as belonging to the Vairocana cycle (Vairocana-kula).2 CMT has been preserved in the Sanskrit original3 and 1 George 1974: xxxvi: “According to formal Tibetan classification, this work is a Vyākhyātantra, or ‘Explanatory’ Tantra, belonging to the school of the Guhyasamāja Tantra, which in turn is one of the five Mūlatantras, or ‘Basic’ Tantras in the class of Anuttarayogatantras”. See also Skorupski 1996. 2 Eimer 1989: 32: “2.3. -

The Relation of Akasa to Pratityasamutpada in Nagarjuna's

The relation of akasa to pratityasamutpada in Nagarjuna’s writings Garth Mason To Juliet, my wife, whose love, acceptance and graceful realism made this thesis possible. To Sinead and Kieran who teach me everyday I would like to thank Professor Deirdre Byrne for her intellectual support and editing the thesis The relation of akasa to pratityasamutpada in Nagarjuna’s writings By Garth Mason Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF LITERATURE AND PHILOSOPHY In the subject of RELIGIOUS STUDIES at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA PROMOTER: PROF. M. CLASQUIN AUGUST 2012 i Summary of thesis: While much of Nāgārjuna’s writings are aimed at deconstructing fixed views and views that hold to some form of substantialist thought (where certain qualities are held to be inherent in phenomena), he does not make many assertive propositions regarding his philosophical position. He focuses most of his writing to applying the prasaṅga method of argumentation to prove the importance of recognizing that all phenomena are śūnya by deconstructing views of phenomena based on substance. Nāgārjuna does, however, assert that all phenomena are empty and that phenomena are meaningful because śūnyatā makes logical sense.1 Based on his deconstruction of prevailing views of substance, he maintains that holding to any view of substance is absurd, that phenomena can only make sense if viewed from the standpoint of śūnyatā. This thesis grapples with the problem that Nāgārjuna does not provide adequate supporting arguments to prove that phenomena are meaningful due to their śūnyatā. It is clear that if saṃvṛti is indiscernible due to its emptiness, saṃvṛtisatya cannot be corroborated on its own terms due to its insubstantiality. -

The Selfless Mind: Personality, Consciousness and Nirvāṇa In

PEI~SONALITY, CONSCIOUSNESS ANI) NII:tVANA IN EAI:tLY BUI)l)HISM PETER HARVEY THE SELFLESS MIND Personality, Consciousness and Nirv3J}.a in Early Buddhism Peter Harvey ~~ ~~~~!;"~~~~urzon LONDON AND NEW YORK First published in 1995 by Curzon Press Reprinted 2004 By RoutledgeCurzon 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Transferred to Digital Printing 2004 RoutledgeCurzon is an imprint ofthe Taylor & Francis Group © 1995 Peter Harvey Typeset in Times by Florencetype Ltd, Stoodleigh, Devon Printed and bound in Great Britain by Biddies Ltd, King's Lynn, Norfolk AU rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any fonn or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any infonnation storage or retrieval system, without pennission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress in Publication Data A catalog record for this book has been requested ISBN 0 7007 0337 3 (hbk) ISBN 0 7007 0338 I (pbk) Ye dhammd hetuppabhavti tesaf{l hetUf{l tathiigato aha Tesaii ca yo norodho evQf{lvtidi mahiisamaf10 ti (Vin.l.40) Those basic processes which proceed from a cause, Of these the tathiigata has told the cause, And that which is their stopping - The great wandering ascetic has such a teaching ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr Karel Werner, of Durham University (retired), for his encouragement and help in bringing this work to publication. I would also like to thank my wife Anne for her patience while I was undertaking the research on which this work is based. -

The Seventy-Five Dharmas (Elements of Existence) in the Abhidharmakosa of Vasubandhu

The Seventy-Five Dharmas (Elements of Existence) in the Abhidharmakosa of Vasubandhu Created Elements, Samskrta-dharma (Dharmas 1-72) I. Forms, Rupani Sense Organs 1. eye, caksu 2. ear, srotra 3. nose, ghrana 4. tongue, jihva 5. body, kaya Sense Objects 6. form, rupa 7. sound, sabda 8. smell, gandha 9. taste. rasa 10. touch, sprastavya 11. element with no manifestation, avijnapti-rupa II. Mind, Citta 12. Mind, Citta III. Concomitant Mental Faculties, Caitasika or Citta-samprayukta-samskara A. General Functions, Mahabhumika 13. feeling, sensation, vedana 14. conception, idea, samjna 15. will, volition, cetana 16. touch, contact, sparsa 17. wish, chanda 18. intellect, mati 19. mindfulness, smrti 20. attention, manaskara 21. decision, abhimoksa 22. concentration, samadhi B. General Functions of Good, Kusala-mahabhumika 23. faith, sraddha 24. energy, effort, virya 25. equanimity, upeksa 26. self respect, shame, hri 27. decorum, apatrapya 28. non-greediness, alobha 29. non-ill-will, advesa 30. non-violence, non-harm, ahimsa 31. confidence, prasrabdhi 32. exertion, apramada C. General Functions of Defilement, Klesa mahabhumika 33. ignorance, moha 34. idleness, non-diligence, pramada 35. indolence, idleness vs. virya, kausidya 36. non-belief, asraddhya 37. low-mindedness, torpor, styana 38. high-mindedness, restlessness, dissipation, auddhatya D. General Functions of Evil, Akusala-mahabhumika 39. lack of self-respect, shamelessness, ahrikya 40. lack of decorum, anapatrapya E. Minor Functions of Defilement, Upaklesa-bhumika 41. anger, krodha 42. concealment, hypocrisy, mraksa 43. parsimony, matsarya 44. jealousy, envy, irsya 45. affliction, pradasa 46. violence, harm, vihimsa 47. enmity, breaking friend, upanaha 48. deceit, maya 49. fraudulence, perfidy, sathya 50. arrogance, mada F.