':~Rt~-·Cosp,· R,'-I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism Key Terms Pairs

Pairs! Cut out the pairs and challenge your classmate to a game of pairs! There are a number of key terms each of which correspond to a teaching or belief. The key concepts are those that are underlined and the others are general words to help your understanding of the concepts. Can you figure them out? Practicing Doctrine of single-pointed impermanence – Non-injury to living meditation through which states nothing things; the doctrine of mindfulness of Anicca ever is but is always in Samatha Ahimsa non-violence. breathing in order to a state of becoming. calm the mind. ‘Foe Destroyer’. A person Phenomena arising who has destroyed all The Buddhist doctrine together in a mutually delusions through Anatta of no-self. Pratitya interdependent web of Arhat training on the spiritual cause and effect. path. They will never be reborn again in Samsara. A person who has Loving-kindness generated spontaneous meditation practiced bodhichitta but who Pain, suffering, disease Metta in order to ‘cultivate has not yet become a and disharmony. Bodhisattva Dukkha loving-kindness’ Buddha; delaying their Bhavana towards others. parinirvana in order to help mankind. Meditation practiced in (Skandhas – Sanskrit): Theravada Buddhism The four sublime The five aggregates involving states: metta, karuna, which make up the Brahmavihara Khandas Vipassana concentration on the mudita and upekkha. self, as we know it. body or its sensations. © WJEC CBAC LTD 2016 Pairs! A being who has completely abandoned Liberation and true Path to the cessation all delusions and their cessation of the cycle of suffering – the Buddha imprints. In general, Enlightenment of Samsara. -

18 Phases Or Realms

Eighteen Realms- dhatus (Elements-dhatus) Feb.16, 2020 1. 12 inputs 6 Types of Consciousness 6 Types of Sense Objects 6 Types of Sense Organs Mind Cons. Mind Objects (thought/idea) Mind Body Cons. Tangible Objects Body Tongue Cons. Taste Tongue Nose Cons. Smell Nose Ear Cons. Sound Ear Eye Cons. Form Eye Mind Forms/Matters1 Consciousness5 Volitions4 Perceptions3 Sensations2 Forms/Matters . Five Aggregates P2. 1. Rupa: Form or (Matter) Aggregate: the Four Great Elements: 1) Solidity, 2) Fluidity, 3) Heat, 4) Wind/Motion which include the five physical sense-organs i.e. the faculties of the eye, ear, nose, tongue, body besides the brain/mind (note: the brain is an organ, not the mind which is an abstract noun). These sense organs are in contact with the external objects of visible form, sound, odor, taste and tangible things and the mind faculty which corresponds to the intangible objects such as thoughts, ideas, and conceptions. 2. Vedana: Sensations- Feelings (generated by the 6 sense organs eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, brain/mind) 3. Samjna: Perception (Conception): The mental function of shape, color, length, pain, pleasure, un-pleasure, neutral. 4. Samskara: Volition-Mental formation: i.e. flashback, will, intention, or the mental function that accounts for craving. 5. Vijnana : Consciousness( Cognition, discrimination-Mano consciousness): the respective consciousness arises when 6 sense organs eye , ear, nose, tongue, body, brain/mind are in contact with the 6 sense objects form , sound, smell, taste, tangible objects , and mental objects. Please be note that Vijnana Consciousness can be further classified into the 6th, 7th and the 8th according to the Vijhanavada (Mere-Mind) School: Mano Consciousness (6th Consciousness): The front 5 senses report to and co-ordinate by the 6th senses in reaction to the 6 sense objects, gather sense data, discriminate, recall it’s the active, coarse and manifest portion of the Manas Vijnanna. -

Lankavatara-Sutra.Pdf

Table of Contents Other works by Red Pine Title Page Preface CHAPTER ONE: - KING RAVANA’S REQUEST CHAPTER TWO: - MAHAMATI’S QUESTIONS I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XIII XIV XV XVI XVII XVIII XIX XX XXI XXII XXIII XXIV XXV XXVI XXVII XXVIII XXIX XXX XXXI XXXII XXXIII XXXIV XXXV XXXVI XXXVII XXXVIII XXXIX XL XLI XLII XLIII XLIV XLV XLVI XLVII XLVIII XLIX L LI LII LIII LIV LV LVI CHAPTER THREE: - MORE QUESTIONS LVII LVII LIX LX LXI LXII LXII LXIV LXV LXVI LXVII LXVIII LXIX LXX LXXI LXXII LXXIII LXXIVIV LXXV LXXVI LXXVII LXXVIII LXXIX CHAPTER FOUR: - FINAL QUESTIONS LXXX LXXXI LXXXII LXXXIII LXXXIV LXXXV LXXXVI LXXXVII LXXXVIII LXXXIX XC LANKAVATARA MANTRA GLOSSARY BIBLIOGRAPHY Copyright Page Other works by Red Pine The Diamond Sutra The Heart Sutra The Platform Sutra In Such Hard Times: The Poetry of Wei Ying-wu Lao-tzu’s Taoteching The Collected Songs of Cold Mountain The Zen Works of Stonehouse: Poems and Talks of a 14th-Century Hermit The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma P’u Ming’s Oxherding Pictures & Verses TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE Zen traces its genesis to one day around 400 B.C. when the Buddha held up a flower and a monk named Kashyapa smiled. From that day on, this simplest yet most profound of teachings was handed down from one generation to the next. At least this is the story that was first recorded a thousand years later, but in China, not in India. Apparently Zen was too simple to be noticed in the land of its origin, where it remained an invisible teaching. -

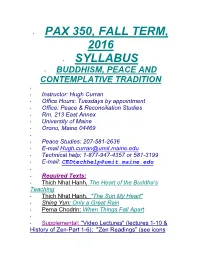

Pax 350, Fall Term, 2016 Syllabus

• PAX 350, FALL TERM, 2016 • SYLLABUS • BUDDHISM, PEACE AND CONTEMPLATIVE TRADITION • • Instructor: Hugh Curran • Office Hours: Tuesdays by appointment • Office: Peace & Reconciliation Studies • Rm. 213 East Annex • University of Maine • Orono, Maine 04469 • • Peace Studies: 207-581-2636 • E-mail [email protected] • Technical help: 1-877-947-4357 or 581-3199 • E-mail: [email protected] • • Required Texts: • Thich Nhat Hanh, The Heart of the Buddha’s Teaching • Thich Nhat Hanh, "The Sun My Heart" • Shing Yun: Only a Great Rain • Pema Chodrin: When Things Fall Apart • • Supplemental: “Video Lectures" (lectures 1-10 & History of Zen-Part 1-6); "Zen Readings” (see icons above lessons): Articles include: The Way of Zen; The Spirit of Zen; Mysticism; Sermons of a Buddhist Abbot ;Dharma Rain; • • Recommended: • Donald Lopez, “The Story of Buddhism” • Dalai Lama: How to Practice Thich Nhat Hanh:"Commentaries on the Heart Sutra" • • The UMA Bookstore 800 number is: 1-800-621- 0083 • The Fax number of the UMA Bookstore is: 1-800- 243-7338The UM Bookstore number is:1-207- 581- 1700 and e-mail at [email protected] • • Course Objective: • Course Objective: • This course is designed as an introduction to Buddhism, especially the practice of Zen (Ch'an). We will examine spiritual & ethical aspects including stories, sutras, ethical precepts, ecological issues, and how we can best embody the Way in our daily lives. • • University Policy: • In complying with the letter and spirit of applicable laws and in pursuing its own goals of pluralism, the University of Maine shall not discriminate on the grounds of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, national origin or citizenship status, age, disability, or veterans status in employment, education, and all other areas of the University. -

Some Reflections on the Place of Philosophy in the Study of Buddhism 145

Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies ^-*/^z ' '.. ' ' ->"•""'",g^ x Volume 18 • Number 2 • Winter 1995 ^ %\ \l '»!#;&' $ ?j On Method \>. :''i.m^--l'-' - -'/ ' x:N'' ••• '; •/ D. SEYFORT RUEGG £>~C~ ~«0 . c/g Some Reflections on the Place of Philosophy in the Study of Buddhism 145 LUIS O. G6MEZ Unspoken Paradigms: Meanderings through the Metaphors of a Field 183 JOSE IGNACIO CABEZ6N Buddhist Studies as a Discipline and the Role of Theory 231 TOM TILLEMANS Remarks on Philology 269 C. W. HUNTINGTON, JR. A Way of Reading 279 JAMIE HUBBARD Upping the Ante: [email protected] 309 D. SEYFORT RUEGG Some Reflections on the Place of Philosophy in the Study of Buddhism I It is surely no exaggeration to say that philosophical thinking constitutes a major component in Buddhism. To say this is of course not to claim that Buddhism is reducible to any single philosophy in some more or less restrictive sense but, rather, to say that what can be meaningfully described as philosophical thinking comprises a major part of its proce dures and intentionality, and also that due attention to this dimension is heuristically necessary in the study of Buddhism. If this proposition were to be regarded as problematic, the difficulty would seem to be due to certain assumptions and prejudgements which it may be worthwhile to consider here. In the first place, even though the philosophical component in Bud dhism has been recognized by many investigators since the inception of Buddhist studies as a modern scholarly discipline more than a century and a half ago, it has to be acknowledged that the main stream of these studies has, nevertheless, quite often paid little attention to the philosoph ical. -

The Role of the Brahmavihāra in Psychotherapeutic Practice

THE ROLE OF THE BRAHMAVIHĀRA IN PSYCHOTHERAPEUTIC PRACTICE The following is an essay written early in 2006 for an MA-course in Buddhist Psychotherapy. It addresses some questions on the relevance and the relationship of a key aspect of Buddhist understanding and prac- tice (namely the Four Brahmavihàra) to the psychotherapeutic setting and, in particular, to their role in Core Process Psychotherapy. ekamantaṃ nisinno kho asibandhakaputto gāmaṇi bhagavantaṃ etadavoca || nanu bhante | bhagavā sabbapāṇabhūtahitānukampī viharatīti || evaṃ gāmaṇi | tathāgato sabbapāṇabhūtahitānukampī viharatīti || (S iv 314) Sitting down to one side the headman Asibandhakaputto addressed the Blessed One thus: »Does the Blessed One abide in compassion and care for the welfare of all sentient beings? – »Ideed, headman, it is so. The Tathāgata abides in compassion and care for the welfare of all sentient beings.« (Saṁyutta Nikāya S 42, 7) The role of the Brahmavihàra in Core Process Psychotherapy – Akincano M. Weber 2006 – 1 – INTRODUCTION Core Process Psychotherapy is a contemplative Psychotherapy and refers explicitly to a Buddhist understanding of health and mind-development (bhàvanà). The following es- say is an attempt to understand the concept of the four Brahmavihàra, their place and function in Buddhist mind-training and to address the questions of how they inform and relate to Core Process Psychotherapy. In PART ONE the first segment of the topic will be contextualised. The teaching of the Four Brahmavihàra in their Indian background will be looked at in some detail and as- pects of the Buddhist teaching on mind-cultivation relevant to Core Process Psycho- therapy will be drawn from. In PART TWO I will be looking briefly at the Western concepts of presence, embodiment, holding environment, relational field and Source-Being-Self. -

A Buddhist Approach Based on Loving- Kindness: the Solution of the Conflict in Modern World

A BUDDHIST APPROACH BASED ON LOVING- KINDNESS: THE SOLUTION OF THE CONFLICT IN MODERN WORLD Venerable Neminda A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Buddhist Studies) Graduate School Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University C.E. 2019 A Buddhist Approach Based on Loving-kindness: The Solution of the Conflict in Modern World Venerable Neminda A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Buddhist Studies) Graduate School Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University C.E. 2019 (Copyright by Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University) Dissertation Title : A Buddhist Approach Based on Loving-Kindness: The Solution of the Conflict in Modern World Researcher : Venerable Neminda Degree : Doctor of Philosophy (Buddhist Studies) Dissertation Supervisory Committee : Phramaha Hansa Dhammahaso, Assoc. Prof. Dr., Pāḷi VI, B.A. (Philosophy), M.A. (Buddhist Studies), Ph.D. (Buddhist Studies) : Asst. Prof. Dr. Sanu Mahatthanadull, B.A. (Advertising) M.A. (Buddhist Studies), Ph.D. (Buddhist Studies) Date of Graduation : February/ 26/ 2019 Abstract The dissertation is a qualitative research. There are three objectives, namely:- 1) To explore the concept of conflict and its cause found in the Buddhist scriptures, 2) To investigate the concept of loving-kindness for solving the conflicts in suttas and the best practices applied by modern scholars 3) To present a Buddhist approach based on loving-kindness: The solution of the conflict in modern world. This finding shows the concept of conflicts and conflict resolution method in the Buddhist scriptures. The Buddhist resolution is the loving-kindness. These loving- kindness approaches provide the method, and integration theory of the Buddhist teachings, best practice of modern scholar method which is resolution method in the modern world. -

A Buddhist Inspiration for a Contemporary Psychotherapy

1 A BUDDHIST INSPIRATION FOR A CONTEMPORARY PSYCHOTHERAPY Gay Watson Thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the School of Oriental & African Studies, University of London. 1996 ProQuest Number: 10731695 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10731695 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ABSTRACT It is almost exactly one hundred years since the popular and not merely academic dissemination of Buddhism in the West began. During this time a dialogue has grown up between Buddhism and the Western discipline of psychotherapy. It is the contention of this work that Buddhist philosophy and praxis have much to offer a contemporary psychotherapy. Firstly, in general, for its long history of the experiential exploration of mind and for the practices of cultivation based thereon, and secondly, more specifically, for the relevance and resonance of specific Buddhist doctrines to contemporary problematics. Thus, this work attempts, on the basis of a three-way conversation between Buddhism, psychotherapy and various themes from contemporary discourse, to suggest a psychotherapy that may be helpful and relevant to the current horizons of thought and contemporary psychopathologies which are substantially different from those prevalent at the time of psychotherapy's early years. -

The Selfless Mind: Personality, Consciousness and Nirvāṇa In

PEI~SONALITY, CONSCIOUSNESS ANI) NII:tVANA IN EAI:tLY BUI)l)HISM PETER HARVEY THE SELFLESS MIND Personality, Consciousness and Nirv3J}.a in Early Buddhism Peter Harvey ~~ ~~~~!;"~~~~urzon LONDON AND NEW YORK First published in 1995 by Curzon Press Reprinted 2004 By RoutledgeCurzon 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Transferred to Digital Printing 2004 RoutledgeCurzon is an imprint ofthe Taylor & Francis Group © 1995 Peter Harvey Typeset in Times by Florencetype Ltd, Stoodleigh, Devon Printed and bound in Great Britain by Biddies Ltd, King's Lynn, Norfolk AU rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any fonn or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any infonnation storage or retrieval system, without pennission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress in Publication Data A catalog record for this book has been requested ISBN 0 7007 0337 3 (hbk) ISBN 0 7007 0338 I (pbk) Ye dhammd hetuppabhavti tesaf{l hetUf{l tathiigato aha Tesaii ca yo norodho evQf{lvtidi mahiisamaf10 ti (Vin.l.40) Those basic processes which proceed from a cause, Of these the tathiigata has told the cause, And that which is their stopping - The great wandering ascetic has such a teaching ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr Karel Werner, of Durham University (retired), for his encouragement and help in bringing this work to publication. I would also like to thank my wife Anne for her patience while I was undertaking the research on which this work is based. -

The Seventy-Five Dharmas (Elements of Existence) in the Abhidharmakosa of Vasubandhu

The Seventy-Five Dharmas (Elements of Existence) in the Abhidharmakosa of Vasubandhu Created Elements, Samskrta-dharma (Dharmas 1-72) I. Forms, Rupani Sense Organs 1. eye, caksu 2. ear, srotra 3. nose, ghrana 4. tongue, jihva 5. body, kaya Sense Objects 6. form, rupa 7. sound, sabda 8. smell, gandha 9. taste. rasa 10. touch, sprastavya 11. element with no manifestation, avijnapti-rupa II. Mind, Citta 12. Mind, Citta III. Concomitant Mental Faculties, Caitasika or Citta-samprayukta-samskara A. General Functions, Mahabhumika 13. feeling, sensation, vedana 14. conception, idea, samjna 15. will, volition, cetana 16. touch, contact, sparsa 17. wish, chanda 18. intellect, mati 19. mindfulness, smrti 20. attention, manaskara 21. decision, abhimoksa 22. concentration, samadhi B. General Functions of Good, Kusala-mahabhumika 23. faith, sraddha 24. energy, effort, virya 25. equanimity, upeksa 26. self respect, shame, hri 27. decorum, apatrapya 28. non-greediness, alobha 29. non-ill-will, advesa 30. non-violence, non-harm, ahimsa 31. confidence, prasrabdhi 32. exertion, apramada C. General Functions of Defilement, Klesa mahabhumika 33. ignorance, moha 34. idleness, non-diligence, pramada 35. indolence, idleness vs. virya, kausidya 36. non-belief, asraddhya 37. low-mindedness, torpor, styana 38. high-mindedness, restlessness, dissipation, auddhatya D. General Functions of Evil, Akusala-mahabhumika 39. lack of self-respect, shamelessness, ahrikya 40. lack of decorum, anapatrapya E. Minor Functions of Defilement, Upaklesa-bhumika 41. anger, krodha 42. concealment, hypocrisy, mraksa 43. parsimony, matsarya 44. jealousy, envy, irsya 45. affliction, pradasa 46. violence, harm, vihimsa 47. enmity, breaking friend, upanaha 48. deceit, maya 49. fraudulence, perfidy, sathya 50. arrogance, mada F. -

The Bodhisattva Ideal in Selected Buddhist

i THE BODHISATTVA IDEAL IN SELECTED BUDDHIST SCRIPTURES (ITS THEORETICAL & PRACTICAL EVOLUTION) YUAN Cl Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 2004 ProQuest Number: 10672873 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672873 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This thesis consists of seven chapters. It is designed to survey and analyse the teachings of the Bodhisattva ideal and its gradual development in selected Buddhist scriptures. The main issues relate to the evolution of the teachings of the Bodhisattva ideal. The Bodhisattva doctrine and practice are examined in six major stages. These stages correspond to the scholarly periodisation of Buddhist thought in India, namely (1) the Bodhisattva’s qualities and career in the early scriptures, (2) the debates concerning the Bodhisattva in the early schools, (3) the early Mahayana portrayal of the Bodhisattva and the acceptance of the six perfections, (4) the Bodhisattva doctrine in the earlier prajhaparamita-siltras\ (5) the Bodhisattva practices in the later prajnaparamita texts, and (6) the evolution of the six perfections (paramita) in a wide range of Mahayana texts. -

1969 01 Jan Vol 16

SOKEI-AN SAYS thing. It is like electricity. No one of the mind and drive out all the the faces of cats and dogs, sometimes TOE FIVE SKANDHAS knows what it is in itself.When elec- things that are smoldering in the the shapes of letters or characters, The five groups of aggregates of tricity relies on something, it burns mind. Just as when a room becomes the forms of bodies,and so forth. all existing dharmas called the five that on which it relies and produces full of cigarette smoke, you open the Vedana- skandha is usually trans- skandhas are the basis for one of the light. When the human soul is in its windows and turn on the electric fan lated by Western scholars as sense- important doctrines in Buddhism. original state, it is called asam- to drive out the smoke, so with medi- perception. It includes feelings- - European and American scholars skrita. When it relies upon something- - tation you must drive out all suffer- pleasant and painful, agreeable and who talk about Buddhism pay little as when electricity relies on some- ing and questions, and keep your mind disagreeable, hunger, itching, and so attention to the five skandhas. Some thing, carbon, iron, or copper wire--i t pure. With this pure mind you will forth. All these belong to vedana. schol ar s who call themselves profound acts differently. It is then said to find your mind's origin. Beauty and ugliness may be included Buddhists have never spoken of this be in the state of samskrita.