The Bodhisattva Ideal in Selected Buddhist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism Key Terms Pairs

Pairs! Cut out the pairs and challenge your classmate to a game of pairs! There are a number of key terms each of which correspond to a teaching or belief. The key concepts are those that are underlined and the others are general words to help your understanding of the concepts. Can you figure them out? Practicing Doctrine of single-pointed impermanence – Non-injury to living meditation through which states nothing things; the doctrine of mindfulness of Anicca ever is but is always in Samatha Ahimsa non-violence. breathing in order to a state of becoming. calm the mind. ‘Foe Destroyer’. A person Phenomena arising who has destroyed all The Buddhist doctrine together in a mutually delusions through Anatta of no-self. Pratitya interdependent web of Arhat training on the spiritual cause and effect. path. They will never be reborn again in Samsara. A person who has Loving-kindness generated spontaneous meditation practiced bodhichitta but who Pain, suffering, disease Metta in order to ‘cultivate has not yet become a and disharmony. Bodhisattva Dukkha loving-kindness’ Buddha; delaying their Bhavana towards others. parinirvana in order to help mankind. Meditation practiced in (Skandhas – Sanskrit): Theravada Buddhism The four sublime The five aggregates involving states: metta, karuna, which make up the Brahmavihara Khandas Vipassana concentration on the mudita and upekkha. self, as we know it. body or its sensations. © WJEC CBAC LTD 2016 Pairs! A being who has completely abandoned Liberation and true Path to the cessation all delusions and their cessation of the cycle of suffering – the Buddha imprints. In general, Enlightenment of Samsara. -

Original Vows of Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva Sutra

Original Vows of Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva Sutra Original Vows of Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva Sutra Translated in English by Jeanne Tsai Fo Guang Shan International Translation Center © 2014, 2015 Fo Guang Shan International Translation Center Translated by Jeanne Tsai Book designed by Xiaoyang Zhang Published by the Fo Guang Shan International Translation Center 3456 Glenmark Drive Hacienda Heights, CA 91745 U.S.A. Tel: (626) 330-8361 / (626) 330-8362 Fax: (626) 330-8363 www.fgsitc.org Protected by copyright under the terms of the International Copyright Union; all rights reserved. Except for fair use in book reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced for any reason by any means, including any method of photographic reproduction, without permission of the publisher. Printed in Taiwan. 18 17 16 15 2 3 4 5 Contents Introduction by Venerable Master Hsing Yun. ix Incense Praise. .1 Sutra Opening Verse. .3 Original Vows of Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva Sutra 1. Spiritual Penetration in Trayastrimsa Heaven. .5 2. The Assembly of the Emanations. 51 3. Observing the Karmic Conditions of Living Beings. .65 4. The Karmic Consequences of Living Beings of Jambudvipa. 87 5. The Names of the Hells. .131 6. The Praise of the Tathagata. 149 7. Benefiting the Living and the Deceased. 187 8. The Praise of King Yama and His Retinue. 207 9. Reciting the Names of Buddhas. 243 10. Comparing the Conditions and Virtues of Giving. .261 11. The Dharma Protection of the Earth Spirit . 283 12. The Benefits from Seeing and Hearing. 295 13. Entrusting Humans and Devas. 343 Praise . .367 Praise of Ksitigarbha Bodhisattva . -

Buddhist Pilgrimage

Published for free distribution Buddhist Pilgrimage New Edition 2009 Chan Khoon San ii Sabbadanam dhammadanam jinati. The Gift of Dhamma excels all gifts. The printing of this book for free distribution is sponsored by the generous donations of Dhamma friends and supporters, whose names appear in the donation list at the end of this book. ISBN 983-40876-0-8 © Copyright 2001 Chan Khoon San irst Printing, 2002 " 2000 copies Second Printing 2005 " 2000 copies New Edition 2009 − 7200 copies All commercial rights reserved. Any reproduction in whole or part, in any form, for sale, profit or material gain is strictly prohibited. However, permission to print this book, in its entirety, for free distribution as a gift of Dhamma, is allowed after prior notification to the author. New Cover Design ,nset photo shows the famous Reclining .uddha image at Kusinara. ,ts uni/ue facial e0pression evokes the bliss of peace 1santisukha2 of the final liberation as the .uddha passes into Mahaparinibbana. Set in the background is the 3reat Stupa of Sanchi located near .hopal, an important .uddhist shrine where relics of the Chief 4isciples and the Arahants of the Third .uddhist Council were discovered. Printed in ,uala -um.ur, 0alaysia 1y 5a6u6aya ,ndah Sdn. .hd., 78, 9alan 14E, Ampang New Village, 78000 Selangor 4arul Ehsan, 5alaysia. Tel: 03-42917001, 42917002, a0: 03-42922053 iii DEDICATI2N This book is dedicated to the spiritual advisors who accompanied the pilgrimage groups to ,ndia from 1991 to 2008. Their guidance and patience, in helping to create a better understanding and appreciation of the significance of the pilgrimage in .uddhism, have made those 6ourneys of faith more meaningful and beneficial to all the pilgrims concerned. -

The Development of Prajna in Buddhism from Early Buddhism to the Prajnaparamita System: with Special Reference to the Sarvastivada Tradition

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies Legacy Theses 2001 The development of Prajna in Buddhism from early Buddhism to the Prajnaparamita system: with special reference to the Sarvastivada tradition Qing, Fa Qing, F. (2001). The development of Prajna in Buddhism from early Buddhism to the Prajnaparamita system: with special reference to the Sarvastivada tradition (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/15801 http://hdl.handle.net/1880/40730 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Dcvelopmcn~of PrajfiO in Buddhism From Early Buddhism lo the Praj~iBpU'ranmirOSystem: With Special Reference to the Sarv&tivada Tradition Fa Qing A DISSERTATION SUBMIWED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF RELIGIOUS STUDIES CALGARY. ALBERTA MARCI-I. 2001 0 Fa Qing 2001 1,+ 1 14~~a",lllbraly Bibliolheque nationale du Canada Ac uisitions and Acquisitions el ~ibqio~raphiiSetvices services bibliogmphiques The author has granted anon- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive pernettant a la National Library of Canada to Eiblioth&quenationale du Canada de reproduce, loao, distribute or sell reproduire, priter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. -

Difference Between the Svatantrika Madhyamika and the Prasangika

Handout 07 - Spring 2011 / Bodhicitta Difference between the Svatantrika Madhyamika and the Prasangika Madhyamika tenets As mentioned in the previous handout (Handout 06), even though the main difference between the two Madhyamika (Middle Way) tenets lies in their interpretation of the ultimate truth, there are several other differences, one of which is outlined during the presentation of aspirational and engaging Bodhicitta. The difference that is outlined here arises from the two tenets' different assertions regarding the nature of vows. Svatantrika Madhyamika (Autonomy Middle Way) tenet From the point of view of the Svatantrika (Autonomy School) tenet -- which includes the Yoga Svatantrika and the Sutra Svatantrika tenets -- aspirational Bodhicitta arises even in the continua of Bodhisattvas who have taken and not transgressed the Bodhisattva vow. The reason for this is that, according to this tenet, vows are a mental factor. Vows are the mental factor of 'intention' which is one of the five omnipresent mental factors that is concomitant with every main mind. This means that whenever vows manifest in someone's continuum they manifest in the form of the mental factor of intention. However, this does not mean that every mental factor of intention (even in the continuum of someone who has taken vows) manifests in the form of vows. In the case of the Bodhisattva vow, it refers to the mental factor of intention that is concomitant with Bodhicitta. Thus, when Bodhisattvas newly take the Bodhisattva vow the vow first arises in their continua in the form of the mental factor of intention that is concomitant with Bodhicitta. In other words, during the ritual of taking the Bodhisattva vow the Bodhisattvas initially generate aspirational Bodhicitta. -

YOGA INFLUENCE YOGA INFLUENCE English Version of YOGAPRABHAVA Discourse by Saint Gulabrao Maharaj on ‘Patanjala Yogasutra’

YOGA INFLUENCE YOGA INFLUENCE English Version of YOGAPRABHAVA Discourse by Saint Gulabrao Maharaj on ‘Patanjala Yogasutra’ Translated By Vasant Joshi Published by Vasant Joshi YOGA INFLUENCE YOGA INFLUENCE English Version of YOGAPRABHAVA Discourse by Saint Gulabrao Maharaj on ‘Patanjala Yogasutra’ * Self Published by: Vasant Joshi English Translator: Vasant Joshi © B-8, Sarasnagar, Siddhivinayak Society, Shukrawar Peth, Pune 411021. Mobile.: +91-9422024655 | Email : [email protected] * All rights reserved with English Translator No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the English Translator. * Typesetting and Formatting Books and Beyond Mrs Ujwala Marne New Ahire Gaon, Warje, Pune. Mobile. : +91-8805412827 / 7058084127 | Email: [email protected] * Preface by : Dr. Vijay Bhatkar, Chief Mentor, Multiversity. * Cover Design by : Aadity Ingawale * First Edition : 26th January 2021 YOGA INFLUENCE DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF G My Brother My Sister Late Prabhakar Joshi Late Sudha Natu yG y YOGA INFLUENCE INDEX Subject Page No. Part I Preface - Dr. Vijay Bhatkar I Prologue of English Translator - Vasant Joshi IV Acquaintance - Dr. K. M. Ghatate VI Autobiography of Saint Gulabrao Maharaj XLII Introduction - Rajeshwar Tripurwar LI Swami Bechiranand - Rajeshwar Tripurwar LVI Tribute - Vasant Joshi LIX Part II Chapter I : Introduction 4 to 37 Aphorism 1 to 22 Chapter II : God Meditation 38 to 163 Aphorism 23 to 33 Chpter III : Study 164 to 300 Aphorism 34 to 39 Chapter IV : Fruit of Yoga Study 301 to 357 Aphorism 40 to 44 Pious Behaviour Indication 358 to 362 Steps Perfection 363 to 370 Part III Appendix : Glossary of Technical Terms 373 to 395 References 396 G YOGA INFLUENCE PART I YOGA INFLUENCE INDEX Subject Page No. -

Buddha Speaks Mahayana Sublime Treasure King Sutra (Also Known As:) Avalokitesvara-Guna-Karanda-Vyuha Sutra Karanda-Vyuha Sutra

Buddha speaks Mahayana Sublime Treasure King Sutra (Also known as:) Avalokitesvara-guna-karanda-vyuha Sutra Karanda-vyuha Sutra (Tripitaka No. 1050) Translated during the Song Dynasty by Kustana Tripitaka Master TinSeekJoy Chapter 1 Thus I have heard: At one time, the Bhagavan was in the Garden of the Benefactor of Orphans and the Solitary, in Jeta Grove, (Jetavana Anathapindada-arama) in Sravasti state, accompanied by 250 great Bhiksu(monk)s, and 80 koti Bodhisattva-Mahasattvas, whose names are: Vajra-pani(Diamond-Hand) Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Wisdom-Insight Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Vajra-sena(Diamond-Army) Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Secret- Store Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Akasa-garbha(Space-Store) Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Sun- Store Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Immovable Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Ratna- pani(Treasure-Hand) Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Samanta-bhadra(Universal-Goodness) Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Achievement of Reality and Eternity Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Eliminate-Obstructions(Sarva-nivaraNaviskambhin) Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Great Diligence and Bravery Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Bhaisajya-raja(Medicine-King) Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Avalokitesvara(Contemplator of the Worlds' Sounds) Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Vajra-dhara(Vajra-Holding) Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Ocean- Wisdom Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, Dharma-Upholding Bodhisattva-Mahasattva, and so on. At that time, there were also many gods of the 32 heavens, leaded by Mahesvara(Great unrestricted God) and Narayana, came to join the congregation. They are: Sakra Devanam Indra the god of heavens, Great -

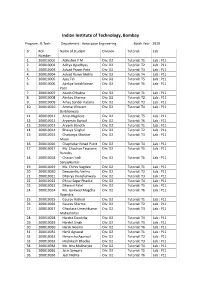

Rolllist Btech DD Bs2020batch

Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay Program : B.Tech. Department : Aerospace Engineering Batch Year : 2020 Sr. Roll Name of Student Division Tutorial Lab Number 1. 200010001 Abhishek P M Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 2. 200010002 Aditya Upadhyay Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 3. 200010003 Advait Pravin Pote Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 4. 200010004 Advait Ranvir Mehla Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 5. 200010005 Ajay Tak Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 6. 200010006 Ajinkya Satishkumar Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Patil 7. 200010007 Akash Chhabra Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 8. 200010008 Akshay Sharma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 9. 200010009 Amay Sunder Kataria Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 10. 200010010 Ammar Khozem Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 Barbhaiwala 11. 200010011 Anup Nagdeve Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 12. 200010012 Aryaman Bansal Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 13. 200010013 Aryank Banoth Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 14. 200010014 Bhavya Singhal Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 15. 200010015 Chaitanya Shankar Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 Moon 16. 200010016 Chaphekar Ninad Punit Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 17. 200010017 Ms. Chauhan Tejaswini Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 Ramdas 18. 200010018 Chavan Yash Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Sanjaykumar 19. 200010019 Ms. Chinni Vagdevi Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 20. 200010020 Deepanshu Verma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 21. 200010021 Dhairya Jhunjhunwala Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 22. 200010022 Dhruv Sagar Phadke Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 23. 200010023 Dhwanil Patel Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 24. -

Buddhist Ethics in Japan and Tibet: a Comparative Study of the Adoption of Bodhisattva and Pratimoksa Precepts

University of San Diego Digital USD Theology and Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship Department of Theology and Religious Studies 1994 Buddhist Ethics in Japan and Tibet: A Comparative Study of the Adoption of Bodhisattva and Pratimoksa Precepts Karma Lekshe Tsomo PhD University of San Diego, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.sandiego.edu/thrs-faculty Part of the Buddhist Studies Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Digital USD Citation Tsomo, Karma Lekshe PhD, "Buddhist Ethics in Japan and Tibet: A Comparative Study of the Adoption of Bodhisattva and Pratimoksa Precepts" (1994). Theology and Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship. 18. https://digital.sandiego.edu/thrs-faculty/18 This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Theology and Religious Studies at Digital USD. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theology and Religious Studies: Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Digital USD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Buddhist Behavioral Codes and the Modern World An Internationa] Symposium Edited by Charles Weihsun Fu and Sandra A. Wawrytko Buddhist Behavioral Codes and the Modern World Recent Titles in Contributions to the Study of Religion Buddhist Behavioral Cross, Crescent, and Sword: The Justification and Limitation of War in Western and Islamic Tradition Codes and the James Turner Johnson and John Kelsay, editors The Star of Return: Judaism after the Holocaust -

The Bodhisattva Precepts

【CONTENTS】 Foreword 03 Introduction 06 The Source of Compassion 10 Who Is a Bodhisattva? 13 How to Overcome Difficulties 15 On Vinaya Practice 20 The Five Precepts 23 The Ten Good Deeds 25 The Three Sets of Pure Precepts 31 On Violation of the Precepts 35 The Four Immeasurable Minds ‥‥ 37 The Four Methods of Inducement 41 Participation in the World ︱ The Bodhisattva Precepts Foreword his book consists of talks on the bodhisattva T precepts by Master Sheng Yen given at the Chan Meditation Center in New York from December 6 through 8, 1997. We sincerely hope that this commentary on the bodhisattva precepts will provide the reader with a clear understanding of their meaning, as well as the inspiration to integrate these teachings into their lives. We wish to acknowledge several individuals for their help in producing this booklet: Guo-gu /translation Simeon Gallu/organization and editorial assistance The International Affairs Office Dharma Drum Mountain January, 2005 Introduction ︱ Introduction here is a saying in Mahayana Buddhism: "Those T who have precepts to break are bodhisattvas; those who have no precepts to break are outer-path followers." Many Buddhists know that receiving the bodhisattva precepts generates great merit, yet they believe this without a real understanding of the profound meaning of the precepts, or of what keeping these precepts entails. They receive the precepts as a matter of course, knowing only that receiving them is a good thing to do. To try to remedy this situation, we are conducting the transmission of the bodhisattva precepts over the course of three days so that prior to the formal transmission ceremony, I can explain to all participants the meaning and significance of these precepts within the Mahayana tradition. -

Lankavatara-Sutra.Pdf

Table of Contents Other works by Red Pine Title Page Preface CHAPTER ONE: - KING RAVANA’S REQUEST CHAPTER TWO: - MAHAMATI’S QUESTIONS I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XIII XIV XV XVI XVII XVIII XIX XX XXI XXII XXIII XXIV XXV XXVI XXVII XXVIII XXIX XXX XXXI XXXII XXXIII XXXIV XXXV XXXVI XXXVII XXXVIII XXXIX XL XLI XLII XLIII XLIV XLV XLVI XLVII XLVIII XLIX L LI LII LIII LIV LV LVI CHAPTER THREE: - MORE QUESTIONS LVII LVII LIX LX LXI LXII LXII LXIV LXV LXVI LXVII LXVIII LXIX LXX LXXI LXXII LXXIII LXXIVIV LXXV LXXVI LXXVII LXXVIII LXXIX CHAPTER FOUR: - FINAL QUESTIONS LXXX LXXXI LXXXII LXXXIII LXXXIV LXXXV LXXXVI LXXXVII LXXXVIII LXXXIX XC LANKAVATARA MANTRA GLOSSARY BIBLIOGRAPHY Copyright Page Other works by Red Pine The Diamond Sutra The Heart Sutra The Platform Sutra In Such Hard Times: The Poetry of Wei Ying-wu Lao-tzu’s Taoteching The Collected Songs of Cold Mountain The Zen Works of Stonehouse: Poems and Talks of a 14th-Century Hermit The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma P’u Ming’s Oxherding Pictures & Verses TRANSLATOR’S PREFACE Zen traces its genesis to one day around 400 B.C. when the Buddha held up a flower and a monk named Kashyapa smiled. From that day on, this simplest yet most profound of teachings was handed down from one generation to the next. At least this is the story that was first recorded a thousand years later, but in China, not in India. Apparently Zen was too simple to be noticed in the land of its origin, where it remained an invisible teaching. -

The Gandavyuha-Sutra : a Study of Wealth, Gender and Power in an Indian Buddhist Narrative

The Gandavyuha-sutra : a Study of Wealth, Gender and Power in an Indian Buddhist Narrative Douglas Edward Osto Thesis for a Doctor of Philosophy Degree School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 2004 1 ProQuest Number: 10673053 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673053 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract The Gandavyuha-sutra: a Study of Wealth, Gender and Power in an Indian Buddhist Narrative In this thesis, I examine the roles of wealth, gender and power in the Mahay ana Buddhist scripture known as the Gandavyuha-sutra, using contemporary textual theory, narratology and worldview analysis. I argue that the wealth, gender and power of the spiritual guides (kalyanamitras , literally ‘good friends’) in this narrative reflect the social and political hierarchies and patterns of Buddhist patronage in ancient Indian during the time of its compilation. In order to do this, I divide the study into three parts. In part I, ‘Text and Context’, I first investigate what is currently known about the origins and development of the Gandavyuha, its extant manuscripts, translations and modern scholarship.