In Search of a Global Theosophical India in Tarakishore Choudhury's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mahabharata

^«/4 •m ^1 m^m^ The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924071123131 ) THE MAHABHARATA OF KlUSHNA-DWAIPAYANA VTASA TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH PROSE. Published and distributed, chiefly gratis, BY PROTSP CHANDRA EOY. BHISHMA PARVA. CALCUTTA i BHiRATA PRESS. No, 1, Raja Gooroo Dass' Stbeet, Beadon Square, 1887. ( The righi of trmsMm is resem^. NOTICE. Having completed the Udyoga Parva I enter the Bhishma. The preparations being completed, the battle must begin. But how dan- gerous is the prospect ahead ? How many of those that were counted on the eve of the terrible conflict lived to see the overthrow of the great Knru captain ? To a KsJtatriya warrior, however, the fiercest in- cidents of battle, instead of being appalling, served only as tests of bravery that opened Heaven's gates to him. It was this belief that supported the most insignificant of combatants fighting on foot when they rushed against Bhishma, presenting their breasts to the celestial weapons shot by him, like insects rushing on a blazing fire. I am not a Kshatriya. The prespect of battle, therefore, cannot be unappalling or welcome to me. On the other hand, I frankly own that it is appall- ing. If I receive support, that support may encourage me. I am no Garuda that I would spurn the strength of number* when battling against difficulties. I am no Arjuna conscious of superhuman energy and aided by Kecava himself so that I may eHcounter any odds. -

YOGA INFLUENCE YOGA INFLUENCE English Version of YOGAPRABHAVA Discourse by Saint Gulabrao Maharaj on ‘Patanjala Yogasutra’

YOGA INFLUENCE YOGA INFLUENCE English Version of YOGAPRABHAVA Discourse by Saint Gulabrao Maharaj on ‘Patanjala Yogasutra’ Translated By Vasant Joshi Published by Vasant Joshi YOGA INFLUENCE YOGA INFLUENCE English Version of YOGAPRABHAVA Discourse by Saint Gulabrao Maharaj on ‘Patanjala Yogasutra’ * Self Published by: Vasant Joshi English Translator: Vasant Joshi © B-8, Sarasnagar, Siddhivinayak Society, Shukrawar Peth, Pune 411021. Mobile.: +91-9422024655 | Email : [email protected] * All rights reserved with English Translator No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the English Translator. * Typesetting and Formatting Books and Beyond Mrs Ujwala Marne New Ahire Gaon, Warje, Pune. Mobile. : +91-8805412827 / 7058084127 | Email: [email protected] * Preface by : Dr. Vijay Bhatkar, Chief Mentor, Multiversity. * Cover Design by : Aadity Ingawale * First Edition : 26th January 2021 YOGA INFLUENCE DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF G My Brother My Sister Late Prabhakar Joshi Late Sudha Natu yG y YOGA INFLUENCE INDEX Subject Page No. Part I Preface - Dr. Vijay Bhatkar I Prologue of English Translator - Vasant Joshi IV Acquaintance - Dr. K. M. Ghatate VI Autobiography of Saint Gulabrao Maharaj XLII Introduction - Rajeshwar Tripurwar LI Swami Bechiranand - Rajeshwar Tripurwar LVI Tribute - Vasant Joshi LIX Part II Chapter I : Introduction 4 to 37 Aphorism 1 to 22 Chapter II : God Meditation 38 to 163 Aphorism 23 to 33 Chpter III : Study 164 to 300 Aphorism 34 to 39 Chapter IV : Fruit of Yoga Study 301 to 357 Aphorism 40 to 44 Pious Behaviour Indication 358 to 362 Steps Perfection 363 to 370 Part III Appendix : Glossary of Technical Terms 373 to 395 References 396 G YOGA INFLUENCE PART I YOGA INFLUENCE INDEX Subject Page No. -

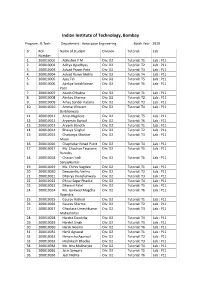

Rolllist Btech DD Bs2020batch

Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay Program : B.Tech. Department : Aerospace Engineering Batch Year : 2020 Sr. Roll Name of Student Division Tutorial Lab Number 1. 200010001 Abhishek P M Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 2. 200010002 Aditya Upadhyay Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 3. 200010003 Advait Pravin Pote Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 4. 200010004 Advait Ranvir Mehla Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 5. 200010005 Ajay Tak Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 6. 200010006 Ajinkya Satishkumar Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Patil 7. 200010007 Akash Chhabra Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 8. 200010008 Akshay Sharma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 9. 200010009 Amay Sunder Kataria Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 10. 200010010 Ammar Khozem Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 Barbhaiwala 11. 200010011 Anup Nagdeve Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 12. 200010012 Aryaman Bansal Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 13. 200010013 Aryank Banoth Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 14. 200010014 Bhavya Singhal Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 15. 200010015 Chaitanya Shankar Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 Moon 16. 200010016 Chaphekar Ninad Punit Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 17. 200010017 Ms. Chauhan Tejaswini Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 Ramdas 18. 200010018 Chavan Yash Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Sanjaykumar 19. 200010019 Ms. Chinni Vagdevi Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 20. 200010020 Deepanshu Verma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 21. 200010021 Dhairya Jhunjhunwala Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 22. 200010022 Dhruv Sagar Phadke Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 23. 200010023 Dhwanil Patel Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 24. -

Uhm Phd 9519439 R.Pdf

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality or the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely. event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. MI48106·1346 USA 313!761-47oo 800:521-0600 Order Number 9519439 Discourses ofcultural identity in divided Bengal Dhar, Subrata Shankar, Ph.D. University of Hawaii, 1994 U·M·I 300N. ZeebRd. AnnArbor,MI48106 DISCOURSES OF CULTURAL IDENTITY IN DIVIDED BENGAL A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE DECEMBER 1994 By Subrata S. -

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa SALYA

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa SALYA PARVA translated by Kesari Mohan Ganguli In parentheses Publications Sanskrit Series Cambridge, Ontario 2002 Salya Parva Section I Om! Having bowed down unto Narayana and Nara, the most exalted of male beings, and the goddess Saraswati, must the word Jaya be uttered. Janamejaya said, “After Karna had thus been slain in battle by Savyasachin, what did the small (unslaughtered) remnant of the Kauravas do, O regenerate one? Beholding the army of the Pandavas swelling with might and energy, what behaviour did the Kuru prince Suyodhana adopt towards the Pandavas, thinking it suitable to the hour? I desire to hear all this. Tell me, O foremost of regenerate ones, I am never satiated with listening to the grand feats of my ancestors.” Vaisampayana said, “After the fall of Karna, O king, Dhritarashtra’s son Suyodhana was plunged deep into an ocean of grief and saw despair on every side. Indulging in incessant lamentations, saying, ‘Alas, oh Karna! Alas, oh Karna!’ he proceeded with great difficulty to his camp, accompanied by the unslaughtered remnant of the kings on his side. Thinking of the slaughter of the Suta’s son, he could not obtain peace of mind, though comforted by those kings with excellent reasons inculcated by the scriptures. Regarding destiny and necessity to be all- powerful, the Kuru king firmly resolved on battle. Having duly made Salya the generalissimo of his forces, that bull among kings, O monarch, proceeded for battle, accompanied by that unslaughtered remnant of his forces. Then, O chief of Bharata’s race, a terrible battle took place between the troops of the Kurus and those of the Pandavas, resembling that between the gods and the Asuras. -

An Appraisal

Adnan Tariq * Muhammad Iqbal Chawla ** FROM COMMUNITARIANISM TO COMMUNALISM, COMMUNITARIAN IDENTITY IN LATE NINETEENTH CENTURY LAHORE: AN APPRAISAL This paper attempts to understand the communitarian sense of awakening in the city of Lahore, which surfaced in the nineteenth century. This communal tangle further transformed into communal bigotry. By the end of the nineteenth century, Lahore had started witnessing the burgeoning communal antagonisms in its colonial inspired cosmopolitanism. Though Muslims were in significant majority, they were deprived in many of the important civic affairs. On the contrary, Hindus were far less in number but having par excellence in many of the socio-economic realm, had upper hand in the civic affairs. Sikhs were the least in numbers in the three-main communities in the colonial Lahore. Every community had grabbed the colonial opportunities according to their socio-economic status; that status-according grabbing resulted into disequilibrium among the communities. At the same time, all the three-main communities had tried to draw their communitarian identity according to the colonial challenges posed by missionaries, interacting and amplifying by the subsequent tussles even among themselves. In that foreground, the retrospective genesis of religious antagonism was transformed into the communitarian and subsequent communal antagonism in the city of Lahore with all of its own peculiarities. Assassination of Lala Lekh Ram testifies that Lahore had entered into the communal antagonism, which sealed the future course up to the coming of partition. Thus, it is indeed important to study the maneuverings of all the three major communities in the city of Lahore while making their identical schemes. -

Use of Theses

THESES SIS/LIBRARY TELEPHONE: +61 2 6125 4631 R.G. MENZIES LIBRARY BUILDING NO:2 FACSIMILE: +61 2 6125 4063 THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY EMAIL: [email protected] CANBERRA ACT 0200 AUSTRALIA USE OF THESES This copy is supplied for purposes of private study and research only. Passages from the thesis may not be copied or closely paraphrased without the written consent of the author. THE PRATYUTPANNA-BUDDHA-SAMMUKHAVASTHITA- SAMADHI-SUTRA AN ANNOTATED ENGLISH TRANSLATION OF THE TIBETAN VERSION WITH SEVERAL APPENDICES A Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Australian National University August, 1979 by Paul Harrison This thesis is based on my own research carried out from 1976 to 1979 at the Australian National University. ABSTRACT The present work consists of a study of the Pratyutpanna-buddha- sammukhavasthita-samadhi-sutra (hereafter: PraS), a relatively early example of Mahayana Buddhist canonical literature. After a brief Intro duction (pp. xxi-xli), which attempts to place the PraS in its historical context, the major portion of the work (pp. 1-186) is devoted to an annotated English translation of the Tibetan version of the sutra, with detailed reference to the three main Chinese translations. Appendix A (pp. 187-252) then attempts a resolution of some of the many problems surrounding the various Chinese versions of the PraS. These are examined both from the point of view of internal evidence and on the basis of bibliographical information furnished by the Chinese Buddhist scripture-catalogues. Some tentative conclusions are advanced concerning the textual history of the PraS in China. -

The Imperial and the Colonized Women's Viewing of the 'Other'

Gazing across the Divide in the Days of the Raj: The Imperial and the Colonized Women’s Viewing of the ‘Other’ Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Vorgelegt von Sukla Chatterjee Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Hans Harder Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Benjamin Zachariah Heidelberg, 01.04.2016 Abstract This project investigates the crucial moment of social transformation of the colonized Bengali society in the nineteenth century, when Bengali women and their bodies were being used as the site of interaction for colonial, social, political, and cultural forces, subsequently giving birth to the ‘new woman.’ What did the ‘new woman’ think about themselves, their colonial counterparts, and where did they see themselves in the newly reordered Bengali society, are some of the crucial questions this thesis answers. Both colonial and colonized women have been secondary stakeholders of colonialism and due to the power asymmetry, colonial woman have found themselves in a relatively advantageous position to form perspectives and generate voluminous discourse on the colonized women. The research uses that as the point of departure and tries to shed light on the other side of the divide, where Bengali women use the residual freedom and colonial reforms to hone their gaze and form their perspectives on their western counterparts. Each chapter of the thesis deals with a particular aspect of the colonized women’s literary representation of the ‘other’. The first chapter on Krishnabhabini Das’ travelogue, A Bengali Woman in England (1885), makes a comparative ethnographic analysis of Bengal and England, to provide the recipe for a utopian society, which Bengal should strive to become. -

Rabindranath's Nationalist Thought

5DELQGUDQDWK¶V1Dtionalist T hought: A Retrospect* Narasingha P. Sil** Abstract : 7DJRUH¶VDQWL-absolutist and anti-statist stand is predicated primarily on his vision of global peace and concord²a world of different peoples and cultures united by amity and humanity. While this grand vision of a brave new world is laudable, it is, nevertheless, constructed on misunderstanding and misreading of history and of the role of the nation state in the West since its rise sometime during the late medieval and early modern times. Tagore views state as an artificial mechanism, indeed a machine thDWWKULYHVRQFRHUFLRQFRQIOLFWDQGWHUURUE\VXEYHUWLQJSHRSOH¶VIUHHGRPDQG culture. This paper seeks to argue that the state also played historically a significant role in enhancing and enriching culture and civilization. His view of an ideal human society is sublime, but by the same token, somewhat ahistorical and anti-modern., K eywords: Anarchism, Babu, Bengal Renaissance, deshaprem [patriotism], bishwajiban [universal life], Gessellschaft, Gemeinschaft, jatiyatabad [nationalism], rastra [state], romantic, samaj [society], swadeshi [indigenous] * $QHDUOLHUVKRUWHUYHUVLRQRIWKLVSDSHUWLWOHG³1DWLRQDOLVP¶V8JO\)DFH7DJRUH¶V7DNH5HYLVLWHG´ZDVSUHVHQWHGWR the Social Science Seminar, Western Oregon University on January 27, 2010 and I thank its convener Professor Eliot Dickinson of the Department of Political Science and Public Administration for inviting me. All citations in Bengali appear in my translation unless stated otherwise. BE stands for Bengali Era that follows the -

Modern-Baby-Names.Pdf

All about the best things on Hindu Names. BABY NAMES 2016 INDIAN HINDU BABY NAMES Share on Teweet on FACEBOOK TWITTER www.indianhindubaby.com Indian Hindu Baby Names 2016 www.indianhindubaby.com Table of Contents Baby boy names starting with A ............................................................................................................................... 4 Baby boy names starting with B ............................................................................................................................. 10 Baby boy names starting with C ............................................................................................................................. 12 Baby boy names starting with D ............................................................................................................................. 14 Baby boy names starting with E ............................................................................................................................. 18 Baby boy names starting with F .............................................................................................................................. 19 Baby boy names starting with G ............................................................................................................................. 19 Baby boy names starting with H ............................................................................................................................. 22 Baby boy names starting with I .............................................................................................................................. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae 1 Name : Mrs. Durga Khatri 2 Designation : Asst. Professor 3 Department : College Education 4 Education Qualification : Level Name of University Year Title/ Remark/ Medal M A MDS University Ajmer 1998 NET UGC 2000 5 Teaching / Research Experience: UG 17.5 Years PG 9 Years Research nil 6 Membership (Academic Bodies): Nil 7 Academic Courses Attended: Course Place Duration Sponsoring Agency Orientation Course jodhpur Jnv 28 days(11.7.2005 to6.8.2005) uni.johpur jodhpur ‘’ 21 days (14.8.2006 to3.9.2006) Refresher jodhpur “ 21 days (31.10.2011 to 19.11.2011) MDSUNI Ajmer 21 days(11.12.2013to 31.12.2013 Ajmer Other (Workshop/ short term course RAJ Summer School/ jaipur 6 days( 3.8.2015to8.82015) Camp etc.) uni.jaipur 1 8 Seminar/ Conference attended: Internat./ Attended/ Name of Seminar/ National/ Paper Title of Paper Date Conference Regional Presented Sansdiy loktantra National conference Paper National Feb 11-12 2006 GOVT. college Barmer presented me girte naitik mulya RGA National conference. Papar Power potential from National 26oct-28oct.2015 GOVT.college Ajmer presented soyabean husk International seminar Paper Rajasthan me aadivasi janjati international Aug.9-10 2016 JNV Uni. Jodhpur presented samuday ;ek vishleshan Rashtriya sangoshthi Vaidik vagnmay me Rajasthan Sanskrit National attened Feb 6-7 2016 paryavaran sanrashan Akadami International conference Paper Guru Jambheshwer international Geeta me Rajniti Dec. 8-10 2016 presented uni.Hisar . Rashtriya Sangoshthi Bharat me Mahila Paper SGSG Govt.college National Manvadhikaron ka Jan. 9,2017 presented Nasirabad sanrakshan Teerth paryatan ke vikas me Rashtriya Sangoshthi Paper 30 Nov.-1 National sarkar ki bhumika evam Govt. -

ESSENCE of VAMANA PURANA Composed, Condensed And

ESSENCE OF VAMANA PURANA Composed, Condensed and Interpreted By V.D.N. Rao, Former General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organisation, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, Union Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India 1 ESSENCE OF VAMANA PURANA CONTENTS PAGE Invocation 3 Kapaali atones at Vaaranaasi for Brahma’s Pancha Mukha Hatya 3 Sati Devi’s self-sacrifice and destruction of Daksha Yagna (Nakshatras and Raashis in terms of Shiva’s body included) 4 Shiva Lingodbhava (Origin of Shiva Linga) and worship 6 Nara Narayana and Prahlada 7 Dharmopadesha to Daitya Sukeshi, his reformation, Surya’s action and reaction 9 Vishnu Puja on Shukla Ekadashi and Vishnu Panjara Stotra 14 Origin of Kurukshetra, King Kuru and Mahatmya of the Kshetra 15 Bali’s victory of Trilokas, Vamana’s Avatara and Bali’s charity of Three Feet (Stutis by Kashyapa, Aditi and Brahma & Virat Purusha Varnana) 17 Parvati’s weds Shiva, Devi Kaali transformed as Gauri & birth of Ganesha 24 Katyayani destroys Chanda-Munda, Raktabeeja and Shumbha-Nikumbha 28 Kartikeya’s birth and his killings of Taraka, Mahisha and Baanaasuras 30 Kedara Kshetra, Murasura Vadha, Shivaabhisheka and Oneness with Vishnu (Upadesha of Dwadasha Narayana Mantra included) 33 Andhakaasura’s obsession with Parvati and Prahlaad’s ‘Dharma Bodha’ 36 ‘Shivaaya Vishnu Rupaaya, Shiva Rupaaya Vishnavey’ 39 Andhakaasura’s extermination by Maha Deva and origin of Ashta Bhairavaas (Andhaka’s eulogies to Shiva and Gauri included) 40 Bhakta Prahlada’s Tirtha Yatras and legends related to the Tirthas 42 -Dundhu Daitya and Trivikrama