The Realisation of the Absolute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ADVAITA-SAADHANAA (Kanchi Maha-Swamigal's Discourses)

ADVAITA-SAADHANAA (Kanchi Maha-Swamigal’s Discourses) Acknowledgement of Source Material: Ra. Ganapthy’s ‘Deivathin Kural’ (Vol.6) in Tamil published by Vanathi Publishers, 4th edn. 1998 URL of Tamil Original: http://www.kamakoti.org/tamil/dk6-74.htm to http://www.kamakoti.org/tamil/dk6-141.htm English rendering : V. Krishnamurthy 2006 CONTENTS 1. Essence of the philosophical schools......................................................................... 1 2. Advaita is different from all these. ............................................................................. 2 3. Appears to be easy – but really, difficult .................................................................... 3 4. Moksha is by Grace of God ....................................................................................... 5 5. Takes time but effort has to be started........................................................................ 7 8. ShraddhA (Faith) Necessary..................................................................................... 12 9. Eligibility for Aatma-SAdhanA................................................................................ 14 10. Apex of Saadhanaa is only for the sannyAsi !........................................................ 17 11. Why then tell others,what is suitable only for Sannyaasis?.................................... 21 12. Two different paths for two different aspirants ...................................................... 21 13. Reason for telling every one .................................................................................. -

YOGA INFLUENCE YOGA INFLUENCE English Version of YOGAPRABHAVA Discourse by Saint Gulabrao Maharaj on ‘Patanjala Yogasutra’

YOGA INFLUENCE YOGA INFLUENCE English Version of YOGAPRABHAVA Discourse by Saint Gulabrao Maharaj on ‘Patanjala Yogasutra’ Translated By Vasant Joshi Published by Vasant Joshi YOGA INFLUENCE YOGA INFLUENCE English Version of YOGAPRABHAVA Discourse by Saint Gulabrao Maharaj on ‘Patanjala Yogasutra’ * Self Published by: Vasant Joshi English Translator: Vasant Joshi © B-8, Sarasnagar, Siddhivinayak Society, Shukrawar Peth, Pune 411021. Mobile.: +91-9422024655 | Email : [email protected] * All rights reserved with English Translator No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the English Translator. * Typesetting and Formatting Books and Beyond Mrs Ujwala Marne New Ahire Gaon, Warje, Pune. Mobile. : +91-8805412827 / 7058084127 | Email: [email protected] * Preface by : Dr. Vijay Bhatkar, Chief Mentor, Multiversity. * Cover Design by : Aadity Ingawale * First Edition : 26th January 2021 YOGA INFLUENCE DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF G My Brother My Sister Late Prabhakar Joshi Late Sudha Natu yG y YOGA INFLUENCE INDEX Subject Page No. Part I Preface - Dr. Vijay Bhatkar I Prologue of English Translator - Vasant Joshi IV Acquaintance - Dr. K. M. Ghatate VI Autobiography of Saint Gulabrao Maharaj XLII Introduction - Rajeshwar Tripurwar LI Swami Bechiranand - Rajeshwar Tripurwar LVI Tribute - Vasant Joshi LIX Part II Chapter I : Introduction 4 to 37 Aphorism 1 to 22 Chapter II : God Meditation 38 to 163 Aphorism 23 to 33 Chpter III : Study 164 to 300 Aphorism 34 to 39 Chapter IV : Fruit of Yoga Study 301 to 357 Aphorism 40 to 44 Pious Behaviour Indication 358 to 362 Steps Perfection 363 to 370 Part III Appendix : Glossary of Technical Terms 373 to 395 References 396 G YOGA INFLUENCE PART I YOGA INFLUENCE INDEX Subject Page No. -

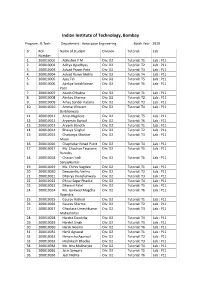

Rolllist Btech DD Bs2020batch

Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay Program : B.Tech. Department : Aerospace Engineering Batch Year : 2020 Sr. Roll Name of Student Division Tutorial Lab Number 1. 200010001 Abhishek P M Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 2. 200010002 Aditya Upadhyay Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 3. 200010003 Advait Pravin Pote Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 4. 200010004 Advait Ranvir Mehla Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 5. 200010005 Ajay Tak Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 6. 200010006 Ajinkya Satishkumar Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Patil 7. 200010007 Akash Chhabra Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 8. 200010008 Akshay Sharma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 9. 200010009 Amay Sunder Kataria Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 10. 200010010 Ammar Khozem Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 Barbhaiwala 11. 200010011 Anup Nagdeve Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 12. 200010012 Aryaman Bansal Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 13. 200010013 Aryank Banoth Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 14. 200010014 Bhavya Singhal Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 15. 200010015 Chaitanya Shankar Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 Moon 16. 200010016 Chaphekar Ninad Punit Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 17. 200010017 Ms. Chauhan Tejaswini Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 Ramdas 18. 200010018 Chavan Yash Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Sanjaykumar 19. 200010019 Ms. Chinni Vagdevi Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 20. 200010020 Deepanshu Verma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 21. 200010021 Dhairya Jhunjhunwala Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 22. 200010022 Dhruv Sagar Phadke Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 23. 200010023 Dhwanil Patel Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 24. -

May I Answer That?

MAY I ANSWER THAT? By SRI SWAMI SIVANANDA SERVE, LOVE, GIVE, PURIFY, MEDITATE, REALIZE Sri Swami Sivananda So Says Founder of Sri Swami Sivananda The Divine Life Society A DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY PUBLICATION First Edition: 1992 Second Edition: 1994 (4,000 copies) World Wide Web (WWW) Reprint : 1997 WWW site: http://www.rsl.ukans.edu/~pkanagar/divine/ This WWW reprint is for free distribution © The Divine Life Trust Society ISBN 81-7502-104-1 Published By THE DIVINE LIFE SOCIETY P.O. SHIVANANDANAGAR—249 192 Distt. Tehri-Garhwal, Uttar Pradesh, Himalayas, India. Publishers’ Note This book is a compilation from the various published works of the holy Master Sri Swami Sivananda, including some of his earliest works extending as far back as the late thirties. The questions and answers in the pages that follow deal with some of the commonest, but most vital, doubts raised by practising spiritual aspirants. What invests these answers and explanations with great value is the authority, not only of the sage’s intuition, but also of his personal experience. Swami Sivananda was a sage whose first concern, even first love, shall we say, was the spiritual seeker, the Yoga student. Sivananda lived to serve them; and this priceless volume is the outcome of that Seva Bhav of the great Master. We do hope that the aspirant world will benefit considerably from a careful perusal of the pages that follow and derive rare guidance and inspiration in their struggle for spiritual perfection. May the holy Master’s divine blessings be upon all. SHIVANANDANAGAR, JANUARY 1, 1993. -

Use of Theses

THESES SIS/LIBRARY TELEPHONE: +61 2 6125 4631 R.G. MENZIES LIBRARY BUILDING NO:2 FACSIMILE: +61 2 6125 4063 THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY EMAIL: [email protected] CANBERRA ACT 0200 AUSTRALIA USE OF THESES This copy is supplied for purposes of private study and research only. Passages from the thesis may not be copied or closely paraphrased without the written consent of the author. THE PRATYUTPANNA-BUDDHA-SAMMUKHAVASTHITA- SAMADHI-SUTRA AN ANNOTATED ENGLISH TRANSLATION OF THE TIBETAN VERSION WITH SEVERAL APPENDICES A Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Australian National University August, 1979 by Paul Harrison This thesis is based on my own research carried out from 1976 to 1979 at the Australian National University. ABSTRACT The present work consists of a study of the Pratyutpanna-buddha- sammukhavasthita-samadhi-sutra (hereafter: PraS), a relatively early example of Mahayana Buddhist canonical literature. After a brief Intro duction (pp. xxi-xli), which attempts to place the PraS in its historical context, the major portion of the work (pp. 1-186) is devoted to an annotated English translation of the Tibetan version of the sutra, with detailed reference to the three main Chinese translations. Appendix A (pp. 187-252) then attempts a resolution of some of the many problems surrounding the various Chinese versions of the PraS. These are examined both from the point of view of internal evidence and on the basis of bibliographical information furnished by the Chinese Buddhist scripture-catalogues. Some tentative conclusions are advanced concerning the textual history of the PraS in China. -

In Search of a Global Theosophical India in Tarakishore Choudhury's

Bharatbhoomi Punyabhoomi: In Search of a Global Theosophical India in Tarakishore Choudhury’s Writings Author: Arkamitra Ghatak Stable URL: http://www.globalhistories.com/index.php/GHSJ/article/view/105 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/GHSJ.2017.105 Source: Global Histories, Vol. 3, No. 1 (Apr. 2017), pp. 39–61 ISSN: 2366-780X Copyright © 2017 Arkamitra Ghatak License URL: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Publisher information: ‘Global Histories: A Student Journal’ is an open-access bi-annual journal founded in 2015 by students of the M.A. program Global History at Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. ‘Global Histories’ is published by an editorial board of Global History students in association with the Freie Universität Berlin. Freie Universität Berlin Global Histories: A Student Journal Friedrich-Meinecke-Institut Koserstraße 20 14195 Berlin Contact information: For more information, please consult our website www.globalhistories.com or contact the editor at: [email protected]. Bharatbhoomi Punyabhoomi: In Search of a Global Theosophical India in Tarakishore Choudhury’s Writings ARKAMITRA GHATAK Arkamitra Ghatak completed her major in History at Presidency University, Kolkata, in 2016, securing the first rank in the order of merit and was awarded the Gold Medal for Academic Ex- cellence. She is currently pursuing a Master in History at Presidency University. Her research interests include intellectual history in its plural spatialities, expressions of feminine subjec- tivities and spiritualities, as well as articulations of power and piety in cultural performances, especially folk festivals. She has presented several research papers at international student seminars organized at Presidency University, Jadavpur University and other organizations. -

YOGA Year 8 Issue 3 March 2019

Year 8 Issue 3 March 2019 YOGA Membership postage: Rs. 100 119-Mar-Y-coverdraft.indd9-Mar-Y-coverdraft.indd 3 99/03/2019/03/2019 111:02:371:02:37 AAMM Hari Om YOGA is compiled, composed and pub lished by the sannyasin disciples of Swami Satyananda Saraswati for the benefit of all people who seek health, happiness and enlightenment. It contains in- formation about the activities of Bihar School of Yoga, Bihar Yoga Bharati, Yoga Publications Trust and Yoga Research Fellowship. Editor: Swami Gyansiddhi Saraswati Assistant Editor: Swami Yogatirth- GUIDELINES FOR SPIRITUAL LIFE ananda Saraswati YOGA is a monthly magazine. Late Talk a little, sleep a little subscriptions include issues from January to December. Watch your speech. Watch every word. Published by Bihar School of Yoga, Speak no word that is impure or vulgar Ganga Darshan, Fort, Munger, Bihar – 811201. or that can hurt the feelings of another. Speak no word that is disrespectful Printed at Thomson Press India Ltd., Haryana – 121007 and contemptuous. Speak measured and sweet words. Think twice before © Bihar School of Yoga 2019 you speak and thrice before you act. Membership is held on a yearly basis. Please send your requests Health is a state in which one sleeps for application and all correspond- well, is at ease, free from any kind ence to: of dis-ease or uneasiness. Regulate Bihar School of Yoga Ganga Darshan the hours of sleep, which should not Fort, Munger, 811201 be more than six hours when you Bihar, India are in good health. This can even be - A self-addressed, stamped envelope reduced to five hours if one does not must be sent along with enquiries to en- have much physical fatigue or heavy sure a response to your request mental strain. -

La Prospettiva Iniziatica Di René Guénon E Le Vie Dell'oriente

MARCO MARINO La prospettiva iniziatica di René Guénon e le Vie dell’Oriente “Egli [Allāh] è più vicino all’uomo della sua vena giugulare” (Qur’ān, L:16) “L’estrema vicinanza è un velo al pari dell’estrema lontananza”. (Ibn ‘Arabī, Futūhāt al-Makkiyya cap. LXXXV) In una pubblicazione precedente1 abbiamo avuto modo di rilevare come l’iniziazione, volta a realizzare la perfetta Conoscenza del Sé, non sia altro che quel processo mediante il quale il fine ultimo dell’Uomo arriva a coincidere con il fine stesso dell’intera Creazione così come essa è eternamente concepita nell’Intelletto divino (ar. ‘aql al-rabbānī). Recita in proposito un celebre hadīth qudsī2: “Ero un Tesoro Nascosto (kanzan makhfīyyan) che desiderava essere Conosciuto, perciò diedi origine alle creature (fakhalaqtu al-khalq) affinché potessero conoscerMi (fa‘rafūnī”) 3. Il Principio (o il Sé, ar. Huwa), che nella sua 1 M. Marino, «Il problema dell’Wujūd tra Guénon e Ibn ‘Arabī: Essere o Esistenza?», in Perennia Verba, n. 12 (2012), pp. 143-276. Il lettore poco uso alla metafisica e all’ontologia islamica è caldamente invitato a studiare tale saggio prima di procedere oltre, dal momento che, per esigenze di sintesi, molte nozioni saranno date per scontate. 2 Lett. “tradizione santa”, detto nel quale il Principio si esprime in prima persona attraverso la bocca del Profeta Muhammad. 3 Su questo celebre hādīth qudsī, cardine centrale di ogni speculazione metafisica in terra d’Islām, vedere Muhyiddīn Ibn ‘Arabī, Al-Futūhāt al-Makkiyya (d’ora in poi Fut.), Būlāq 1911 (rist. Beirut [s.d.], vol. II p. -

Modern-Baby-Names.Pdf

All about the best things on Hindu Names. BABY NAMES 2016 INDIAN HINDU BABY NAMES Share on Teweet on FACEBOOK TWITTER www.indianhindubaby.com Indian Hindu Baby Names 2016 www.indianhindubaby.com Table of Contents Baby boy names starting with A ............................................................................................................................... 4 Baby boy names starting with B ............................................................................................................................. 10 Baby boy names starting with C ............................................................................................................................. 12 Baby boy names starting with D ............................................................................................................................. 14 Baby boy names starting with E ............................................................................................................................. 18 Baby boy names starting with F .............................................................................................................................. 19 Baby boy names starting with G ............................................................................................................................. 19 Baby boy names starting with H ............................................................................................................................. 22 Baby boy names starting with I .............................................................................................................................. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae 1 Name : Mrs. Durga Khatri 2 Designation : Asst. Professor 3 Department : College Education 4 Education Qualification : Level Name of University Year Title/ Remark/ Medal M A MDS University Ajmer 1998 NET UGC 2000 5 Teaching / Research Experience: UG 17.5 Years PG 9 Years Research nil 6 Membership (Academic Bodies): Nil 7 Academic Courses Attended: Course Place Duration Sponsoring Agency Orientation Course jodhpur Jnv 28 days(11.7.2005 to6.8.2005) uni.johpur jodhpur ‘’ 21 days (14.8.2006 to3.9.2006) Refresher jodhpur “ 21 days (31.10.2011 to 19.11.2011) MDSUNI Ajmer 21 days(11.12.2013to 31.12.2013 Ajmer Other (Workshop/ short term course RAJ Summer School/ jaipur 6 days( 3.8.2015to8.82015) Camp etc.) uni.jaipur 1 8 Seminar/ Conference attended: Internat./ Attended/ Name of Seminar/ National/ Paper Title of Paper Date Conference Regional Presented Sansdiy loktantra National conference Paper National Feb 11-12 2006 GOVT. college Barmer presented me girte naitik mulya RGA National conference. Papar Power potential from National 26oct-28oct.2015 GOVT.college Ajmer presented soyabean husk International seminar Paper Rajasthan me aadivasi janjati international Aug.9-10 2016 JNV Uni. Jodhpur presented samuday ;ek vishleshan Rashtriya sangoshthi Vaidik vagnmay me Rajasthan Sanskrit National attened Feb 6-7 2016 paryavaran sanrashan Akadami International conference Paper Guru Jambheshwer international Geeta me Rajniti Dec. 8-10 2016 presented uni.Hisar . Rashtriya Sangoshthi Bharat me Mahila Paper SGSG Govt.college National Manvadhikaron ka Jan. 9,2017 presented Nasirabad sanrakshan Teerth paryatan ke vikas me Rashtriya Sangoshthi Paper 30 Nov.-1 National sarkar ki bhumika evam Govt. -

Brahma Sutra

BRAHMA SUTRA CHAPTER 1 1st Pada 1st Adikaranam to 11th Adhikaranam Sutra 1 to 31 INDEX S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No Summary 5 Introduction of Brahma Sutra 6 1 Jijnasa adhikaranam 1 a) Sutra 1 103 1 1 2 Janmady adhikaranam 2 a) Sutra 2 132 2 2 3 Sastrayonitv adhikaranam 3 a) Sutra 3 133 3 3 4 Samanvay adhikaranam 4 a) Sutra 4 204 4 4 5 Ikshatyadyadhikaranam: (Sutras 5-11) 5 a) Sutra 5 324 5 5 b) Sutra 6 353 5 6 c) Sutra 7 357 5 7 d) Sutra 8 362 5 8 e) Sutra 9 369 5 9 f) Sutra 10 372 5 10 g) Sutra 11 376 5 11 2 S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No 6 Anandamayadhikaranam: (Sutras 12-19) 6 a) Sutra 12 382 6 12 b) Sutra 13 394 6 13 c) Sutra 14 397 6 14 d) Sutra 15 407 6 15 e) Sutra 16 411 6 16 f) Sutra 17 414 6 17 g) Sutra 18 416 6 18 h) Sutra 19 425 6 19 7 Antaradhikaranam: (Sutras 20-21) 7 a) Sutra 20 436 7 20 b) Sutra 21 448 7 21 8 Akasadhikaranam : 8 a) Sutra 22 460 8 22 9 Pranadhikaranam : 9 a) Sutra 23 472 9 23 3 S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No 10 Jyotischaranadhikaranam : (Sutras 24-27) 10 a) Sutra 24 486 10 24 b) Sutra 25 508 10 25 c) Sutra 26 513 10 26 d) Sutra 27 517 10 27 11 Pratardanadhikaranam: (Sutras 28-31) 11 a) Sutra 28 526 11 28 b) Sutra 29 538 11 29 c) Sutra 30 546 11 30 d) Sutra 31 558 11 31 4 SUMMARY Brahma Sutra Bhasyam Topics - 191 Chapter – 1 Chapter – 2 Chapter – 3 Chapter – 4 Samanvaya – Avirodha – non – Sadhana – spiritual reconciliation through Phala – result contradiction practice proper interpretation Topics - 39 Topics - 47 Topics - 67 Topics 38 Sections Topics Sections Topics Sections Topics Sections Topics 1 11 1 13 1 06 1 14 2 07 2 08 2 08 2 11 3 13 3 17 3 36 3 06 4 08 4 09 4 17 4 07 5 Lecture – 01 Puja: • Gratitude to lord for completion of Upanishad course (last Chandogya Upanishad + Brihadaranyaka Upanishad). -

Vivekachudamani

Adi Sankaracharya’s VIVEKACHUDAMANI Important Verses Topic wise Index SR. No Topics Verse 1 Devoted dedication 1 2 Glory of Spiritual life 2 3 Unique graces in life 3 4 Miseries of the unspiritual man 4 to 7 5 Means of Wisdom 8 to 13 6 The fit Student 14 to 17 7 The four qualifications 18 to 30 8 Bhakti - Firm and deep 31 9 Courtesy of approach and questioning 32 to 40 10 Loving advice of the Guru 41 to 47 11 Questions of the disciple 48 to 49 12 Intelligent disciple - Appreciated 50 13 Glory of self - Effort 51 to 55 14 Knowledge of the self its - Beauty 56 to 61 15 Direct experience : Liberation 62 to 66 16 Discussion on question raised 67 to 71 i SR. No Topics Verse 17 Gross body 72 to 75 18 Sense Objects, a trap : Man bound 76 to 82 19 Fascination for body Criticised 83 to 86 20 Gross body condemned 87 to 91 21 Organs of perception and action 92 22 Inner instruments 93 to 94 23 The five Pranas 95 24 Subtle body : Effects 96 to 101 25 Functions of Prana 102 26 Ego Discussed(Good) 103 to 105 27 Infinite love - The self 106 to 107 28 Maya pointed out 108 to 110 29 Rajo Guna - Nature and Effects 111 to 112 30 Tamo Guna - Nature and effects 113 to 116 31 Sattwa Guna - Nature and effects 117 to 119 32 Causal body - its nature 120 to 121 33 Not - self – Description 122 to 123 ii 34 The self - its Nature 124 to 135 SR.