The Era of Science Enthusiasts in Bengal (1841-1891): Akshayakumar, Vidyasagar and Rajendralala

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vidyasagar College of Optometry and Vision Science

BACHELOR IN OPTOMETRY (B.OPTOM) PROGRAMME • FOUR YEAR DEGREE PROGRAMME College Vidyasagar and Vision Science and Vision of Optometry VCOVS WWW.VCOVS.ORG [email protected] About Optometry Optometry is a healthcare profes- registered), and optometrists are sion concerned with the health of the the primary healthcare practition- eyes and related structures, as well ers of the eye and visual system who as vision, visual systems, and vision provide comprehensive eye and information processing in humans. vision care, which includes refrac- tion and dispensing, detection/di- The World Council of Optometry agnosis and management of disease defines Optometry as ahealth - in the eye, and the rehabilitation care profession that is autonomous, of conditions of the visual system. educated, and regulated (licensed or Optometrists An optometrist is an independent CAREER AND SCOPE primary health care provider who ex- All optometrists provide general amines, diagnoses, treats and manages eye and vision care. diseases and disorders of the visual Some optometrists work in a system, the eye and associated struc- general practice, and other optom- tures. etrists work in a more specialized Among the services optometrists render practice such as: are: prescribing glasses and contact lenses, rehabilitation of the visually Contact lenses impaired, and the diagnosis and treat- Geriatrics people in the ment of ocular diseases. Low vision services (for visually 285 world are blind or impaired patients) visually impaired million Occupational vision (to protect -

Uhm Phd 9519439 R.Pdf

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality or the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely. event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. MI48106·1346 USA 313!761-47oo 800:521-0600 Order Number 9519439 Discourses ofcultural identity in divided Bengal Dhar, Subrata Shankar, Ph.D. University of Hawaii, 1994 U·M·I 300N. ZeebRd. AnnArbor,MI48106 DISCOURSES OF CULTURAL IDENTITY IN DIVIDED BENGAL A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE DECEMBER 1994 By Subrata S. -

Contribution of British East India Company on Medical College

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention (IJHSSI) ISSN (Online): 2319 – 7722, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 7714 www.ijhssi.org ||Volume 8 Issue 11 Ser. I || November 2019 || PP 75-76 Contribution of british east india company on Medical college Mr. Sk Ahammad Raja Post graduation pass in History from Netaji Subhas Open University in 2018. ABSTRACT – The east India company played a very important in history of India. Many historians and many books as tells us something about their persecution same time we come to know some good work also of them. Therefore, let us discuss some good views of them. They brought modern technology of medication. Keywords – Background of establishing a medical college, the Old system of medication was not so good, Establishment of Kolkata Medical College, Student Admission, Anatomy and dissection of the body. Education Methods College building ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- --------- Date of Submission: 27-10-2019 Date of acceptance: 15-11-2019 ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- --------- I. INTRODUCTION - During the reign of Governor-General Lord William Bentinck in 1835. A new chapter in the history of medical science of India and medical science established at Medical College, Kolkata Started The proposal that Bentick and his council adopted was: "That a new College shall be formed for the instruction of a certain number of native youths in the various Branches of medical science ". In an earlier proposal, they rubbed off conventional Native Medical .Medical classes that took place at Institution and Sanskrit College and Madrase were canceled. Bentick Determine that the college will be under the supervision of the Education Committee. Background of establishing a medical collage In Bengal before the establishment of a medical college in 1835 There were various types of errors and weaknesses in medical education. -

Historical Notes: Indian Renaissance: the Making of Modern India

Indian Journal of History of Science, 46.1 (2011) 131-154 HISTORICAL NOTES INDIAN RENAISSANCE: THE MAKING OF MODERN INDIA Sisir K. Majumdar* (Received 16 July 2010) Introduction The history of the Indian renaissance in the 19th century and the European Renaissance in the 14th century offers us a pleasant contrast and also a curious scenario of creative synthesis of the best of the East and the West. With the adoption of English as the official language of British India in 1834, a phase of confrontation, co-operation and imitation started. But the main outcome was the resurrection of nationalist ideals and perceptions in the newly growing urban centers of India—a definite re-awakening; a new renainssance became noticeable. All other negative aspects silently slipped into oblivion and obscurity. The cultural and intellectual heritage of modern India derives largely from this phase of questioning and search. This was the beginning of the making of modern India. It generated an inner quality of earnest inquiry and search, of contemplation and action, of balance and equilibrium, in spite of conflict and contradiction. There was a poise in it and a unity in the midst of disparity and diversity, and its temper was one of supremacy over the changing environment, not by seeking escape from it, but fitting in with it, in order to move with the dynamic history of changing world. Ram Mohan: The First of the Moderns Politically, the period of ten decades between the Battle of Plassey (1757) and the Sepoy Mutiny (1857) was the era of expansion of the British Empire in India and of its subsequent consolidation. -

Annual Report, 2012-13 1 Head of the Department

Annual Report, 2012-13 1 CHAPTER II DEPARTMENT OF BENGALI Head of the Department : SIBABRATA CHATTOPADHYAY Teaching Staff : (as on 31.05.2013) Professor : Dr. Krishnarup Chakraborty, M.A., Ph.D Dr. Asish Kr. Dey, M.A., Ph.D Dr Amitava Das, M.A., Ph.D Dr. Sibabrata Chattopadhyay, M.A., Ph.D Dr. Arun Kumar Ghosh, M.A., Ph.D Dr Uday Chand Das, M.A., Ph.D Associate Professor : Dr Ramen Kr Sar, M.A., Ph.D Dr. Arindam Chottopadhyay, M.A., Ph.D Dr Anindita Bandyopadhyay, M.A., Ph.D Dr. Alok Kumar Chakraborty, M.A., Ph.D Assistant Professor : Ms Srabani Basu, M.A. Field of Studies : A) Mediaval Bengali Lit. B) Fiction & Short Stories, C) Tagore Lit. D) Drama Student Enrolment: Course(s) Men Women Total Gen SC ST Total Gen SC ST Total Gen SC ST Total MA/MSc/MCom 1st Sem 43 25 09 77 88 17 03 108 131 42 12 185 2nd Sem 43 25 09 77 88 17 03 108 131 42 12 185 3rd Sem 43 28 08 79 88 16 02 106 131 44 10 185 4th Sem 43 28 08 79 88 16 02 106 131 44 10 185 M.Phil 01 01 01 01 02 02 01 03 Research Activities :(work in progress) Sl.No. Name of the Scholar(s) Topic of Research Supervisor(s) 1. Anjali Halder Binoy Majumdarer Kabitar Nirmanshaily Prof Amitava Das 2. Debajyoti Debnath Unishsho-sottor paraborti bangla akhayaner dhara : prekshit ecocriticism Prof Uday Chand Das 3. Prabir Kumar Baidya Bangla sahitye patrikar kromobikas (1851-1900) Dr.Anindita Bandyopadhyay 4. -

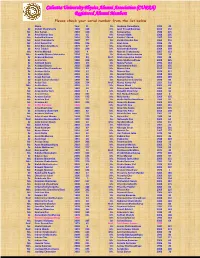

Calcutta University Physics Alumni Association (CUPAA) Registered Alumni Members Please Check Your Serial Number from the List Below Name Year Sl

Calcutta University Physics Alumni Association (CUPAA) Registered Alumni Members Please check your serial number from the list below Name Year Sl. Dr. Joydeep Chowdhury 1993 45 Dr. Abhijit Chakraborty 1990 128 Mr. Jyoti Prasad Banerjee 2010 152 Mr. Abir Sarkar 2010 150 Dr. Kalpana Das 1988 215 Dr. Amal Kumar Das 1991 15 Mr. Kartick Malik 2008 205 Ms. Ambalika Biswas 2010 176 Prof. Kartik C Ghosh 1987 109 Mr. Amit Chakraborty 2007 77 Dr. Kartik Chandra Das 1960 210 Mr. Amit Kumar Pal 2006 136 Dr. Keya Bose 1986 25 Mr. Amit Roy Chowdhury 1979 47 Ms. Keya Chanda 2006 148 Dr. Amit Tribedi 2002 228 Mr. Krishnendu Nandy 2009 209 Ms. Amrita Mandal 2005 4 Mr. Mainak Chakraborty 2007 153 Mrs. Anamika Manna Majumder 2004 95 Dr. Maitree Bhattacharyya 1983 16 Dr. Anasuya Barman 2000 84 Prof. Maitreyee Saha Sarkar 1982 48 Dr. Anima Sen 1968 212 Ms. Mala Mukhopadhyay 2008 225 Dr. Animesh Kuley 2003 29 Dr. Malay Purkait 1992 144 Dr. Anindya Biswas 2002 188 Mr. Manabendra Kuiri 2010 155 Ms. Anindya Roy Chowdhury 2003 63 Mr. Manas Saha 2010 160 Dr. Anirban Guha 2000 57 Dr. Manasi Das 1974 117 Dr. Anirban Saha 2003 51 Dr. Manik Pradhan 1998 129 Dr. Anjan Barman 1990 66 Ms. Manjari Gupta 2006 189 Dr. Anjan Kumar Chandra 1999 98 Dr. Manjusha Sinha (Bera) 1970 89 Dr. Ankan Das 2000 224 Prof. Manoj Kumar Pal 1951 218 Mrs. Ankita Bose 2003 52 Mr. Manoj Marik 2005 81 Dr. Ansuman Lahiri 1982 39 Dr. Manorama Chatterjee 1982 44 Mr. Anup Kumar Bera 2004 3 Mr. -

The Imperial and the Colonized Women's Viewing of the 'Other'

Gazing across the Divide in the Days of the Raj: The Imperial and the Colonized Women’s Viewing of the ‘Other’ Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Vorgelegt von Sukla Chatterjee Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Hans Harder Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Benjamin Zachariah Heidelberg, 01.04.2016 Abstract This project investigates the crucial moment of social transformation of the colonized Bengali society in the nineteenth century, when Bengali women and their bodies were being used as the site of interaction for colonial, social, political, and cultural forces, subsequently giving birth to the ‘new woman.’ What did the ‘new woman’ think about themselves, their colonial counterparts, and where did they see themselves in the newly reordered Bengali society, are some of the crucial questions this thesis answers. Both colonial and colonized women have been secondary stakeholders of colonialism and due to the power asymmetry, colonial woman have found themselves in a relatively advantageous position to form perspectives and generate voluminous discourse on the colonized women. The research uses that as the point of departure and tries to shed light on the other side of the divide, where Bengali women use the residual freedom and colonial reforms to hone their gaze and form their perspectives on their western counterparts. Each chapter of the thesis deals with a particular aspect of the colonized women’s literary representation of the ‘other’. The first chapter on Krishnabhabini Das’ travelogue, A Bengali Woman in England (1885), makes a comparative ethnographic analysis of Bengal and England, to provide the recipe for a utopian society, which Bengal should strive to become. -

In Search of a Global Theosophical India in Tarakishore Choudhury's

Bharatbhoomi Punyabhoomi: In Search of a Global Theosophical India in Tarakishore Choudhury’s Writings Author: Arkamitra Ghatak Stable URL: http://www.globalhistories.com/index.php/GHSJ/article/view/105 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17169/GHSJ.2017.105 Source: Global Histories, Vol. 3, No. 1 (Apr. 2017), pp. 39–61 ISSN: 2366-780X Copyright © 2017 Arkamitra Ghatak License URL: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Publisher information: ‘Global Histories: A Student Journal’ is an open-access bi-annual journal founded in 2015 by students of the M.A. program Global History at Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. ‘Global Histories’ is published by an editorial board of Global History students in association with the Freie Universität Berlin. Freie Universität Berlin Global Histories: A Student Journal Friedrich-Meinecke-Institut Koserstraße 20 14195 Berlin Contact information: For more information, please consult our website www.globalhistories.com or contact the editor at: [email protected]. Bharatbhoomi Punyabhoomi: In Search of a Global Theosophical India in Tarakishore Choudhury’s Writings ARKAMITRA GHATAK Arkamitra Ghatak completed her major in History at Presidency University, Kolkata, in 2016, securing the first rank in the order of merit and was awarded the Gold Medal for Academic Ex- cellence. She is currently pursuing a Master in History at Presidency University. Her research interests include intellectual history in its plural spatialities, expressions of feminine subjec- tivities and spiritualities, as well as articulations of power and piety in cultural performances, especially folk festivals. She has presented several research papers at international student seminars organized at Presidency University, Jadavpur University and other organizations. -

Courses Taught at Both the Undergraduate and the Postgraduate Levels

Jadavpur University Faculty of Arts Department of History SYLLABUS Preface The Department of History, Jadavpur University, was born in August 1956 because of the Special Importance Attached to History by the National Council of Education. The necessity for reconstructing the history of humankind with special reference to India‘s glorious past was highlighted by the National Council in keeping with the traditions of this organization. The subsequent history of the Department shows that this centre of historical studies has played an important role in many areas of historical knowledge and fundamental research. As one of the best centres of historical studies in the country, the Department updates and revises its syllabi at regular intervals. It was revised last in 2008 and is again being revised in 2011.The syllabi that feature in this booklet have been updated recently in keeping with the guidelines mentioned in the booklet circulated by the UGC on ‗Model Curriculum‘. The course contents of a number of papers at both the Undergraduate and Postgraduate levels have been restructured to incorporate recent developments - political and economic - of many regions or countries as well as the trends in recent historiography. To cite just a single instance, as part of this endeavour, the Department now offers new special papers like ‗Social History of Modern India‘ and ‗History of Science and Technology‘ at the Postgraduate level. The Department is the first in Eastern India and among the few in the country, to introduce a full-scale specialization on the ‗Social History of Science and Technology‘. The Department recently qualified for SAP. -

Journal of Bengali Studies

ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Vol. 6 No. 1 The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 1 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426), Vol. 6 No. 1 Published on the Occasion of Dolpurnima, 16 Phalgun 1424 The Theme of this issue is The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century 2 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 ISSN 2277-9426 Journal of Bengali Studies Volume 6 Number 1 Dolpurnima 16 Phalgun 1424 1 March 2018 Spring Issue The Age of Bhadralok: Bengal's Long Twentieth Century Editorial Board: Tamal Dasgupta (Editor-in-Chief) Amit Shankar Saha (Editor) Mousumi Biswas Dasgupta (Editor) Sayantan Thakur (Editor) 3 | Journal of Bengali Studies (ISSN 2277-9426) Vol. 6 No. 1 Copyrights © Individual Contributors, while the Journal of Bengali Studies holds the publishing right for re-publishing the contents of the journal in future in any format, as per our terms and conditions and submission guidelines. Editorial©Tamal Dasgupta. Cover design©Tamal Dasgupta. Further, Journal of Bengali Studies is an open access, free for all e-journal and we promise to go by an Open Access Policy for readers, students, researchers and organizations as long as it remains for non-commercial purpose. However, any act of reproduction or redistribution (in any format) of this journal, or any part thereof, for commercial purpose and/or paid subscription must accompany prior written permission from the Editor, Journal of Bengali Studies. -

Hinduism” and the Problem of Self- Actualisation in the Colonial Era: Critical Reflections

SOUTH ASIA INSTITUTE PAPERS BEITRÄGE DES SÜDASIEN-INSTITUTS HEIDELBERG Amiya P. Sen (Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi) “Hinduism” and the Problem of Self- Actualisation in the Colonial Era: Critical Reflections CONTACT South Asia Institute Heidelberg University Im Neuenheimer Feld 330 D-69120 Heidelberg ISSUE 01 2015 P: +49(0)6221-548900 21. 8. 2015 F: +49(0)6221-544998 [email protected] ISSN 2365-399X www.sai.uni-heidelberg.de “Hinduism” and the Problem of Self-Actualisation in the Colonial Era: Critical Reflections Amiya P. Sen This paper is the text of a lecture delivered at the South Asia Institute, Hei- delberg, on May 20, 2015, with footnotes added. It discusses how schol- arly perceptions of colonial Hinduism have visibly shifted trajectory over the years. Relating how Hinduism has moved from being ‘discovered’ in the eighteenth century to be seen as discursively ‘invented’ or ‘imagined’ in the nineteenth, it argues that in colonial India, internally generated debates about the origin and nature of Hinduism paralleled ascriptions originating outside but failed to attract adequate attention. It also seeks to ask if not also to definitively answer certain key theoretical questions. For instance, even allowing for the fact that social and religious identities are always po- rous, does it still make sense to ask if unstable and fluid perceptions of the self too were invested with some meaning? I His Excellency, M. Sevela Naik, Consul General of India at Munich; Prof. Ger- rit Kloss, Dean, Philosophical Faculty; Prof. Stefan Klonner, Executive Direc- tor, SAI; Professor Gita Dharampal Frick, Head, Department of History, SAI; Dr. -

List of Books Available on Calibre Software

LIST OF BOOKS AVAILABLE ON CALIBRE SOFTWARE (PLEASE CONTACT LIBRARY STAFF TO ACCESS CALIBRE) 1. 1.doc · Kamal Swaroop 2. 50 Volume RGS Journal Table of Contents s · Unknown 3. 1836 Asiatic Researches Vol 19 Part 1 s+m · Unknown 4. 1839 Asiatic Researches Vol 19 Part 2 : THE HISTORY, THE ANTIQUITIES, THE ARTS AND SCIENCES, AND LITERATURE ASIA . · Asiatic Society, Calcutta 5. 1839 Asiatic Researches Vol 19 Part 2 s+m · Unknown 6. 1840 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 8 Part 1 s+m · Unknown 7. 1840 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 8 Part 2 s+m · Unknown 8. 1840 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 9 Part 1 s+m · Unknown 9. 1856 JASB Index AR 19 to JASB 23 · Unknown 10. 1856 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 24 s+m · Unknown 11. 1862 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 30 s+m · Unknown 12. 1866 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 34 s+m · Unknown 13. 1867 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 35 s+m · Unknown 14. 1875 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 44 Part 1 s+m · Unknown 15. 1875 Journal Asiatic Society of Bengal Vol 44 Part 2 s+m · Unknown 16. 1951-52.PMD · Unknown 17. 1952-53-(Final).PMD · Unknown 18. 1953-54.pmd · Unknown 19. 1954-55.pmd · Unknown 20. 1955-56.pmd · Unknown 21. 1956-57.pmd · Unknown 22. 1957-58(interim) 1957-58-1958-59 · Unknown 23. 62569973-Text-of-Justice-Soumitra-Sen-s-Defence · Unknown 24. ([Views of the East; Comprising] India, Canton, [And the Shores of the Red Sea · Robert Elliot 25.