Brahmavihara Meditation & Its Potential Benefits for a Harmonious Workplace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism Key Terms Pairs

Pairs! Cut out the pairs and challenge your classmate to a game of pairs! There are a number of key terms each of which correspond to a teaching or belief. The key concepts are those that are underlined and the others are general words to help your understanding of the concepts. Can you figure them out? Practicing Doctrine of single-pointed impermanence – Non-injury to living meditation through which states nothing things; the doctrine of mindfulness of Anicca ever is but is always in Samatha Ahimsa non-violence. breathing in order to a state of becoming. calm the mind. ‘Foe Destroyer’. A person Phenomena arising who has destroyed all The Buddhist doctrine together in a mutually delusions through Anatta of no-self. Pratitya interdependent web of Arhat training on the spiritual cause and effect. path. They will never be reborn again in Samsara. A person who has Loving-kindness generated spontaneous meditation practiced bodhichitta but who Pain, suffering, disease Metta in order to ‘cultivate has not yet become a and disharmony. Bodhisattva Dukkha loving-kindness’ Buddha; delaying their Bhavana towards others. parinirvana in order to help mankind. Meditation practiced in (Skandhas – Sanskrit): Theravada Buddhism The four sublime The five aggregates involving states: metta, karuna, which make up the Brahmavihara Khandas Vipassana concentration on the mudita and upekkha. self, as we know it. body or its sensations. © WJEC CBAC LTD 2016 Pairs! A being who has completely abandoned Liberation and true Path to the cessation all delusions and their cessation of the cycle of suffering – the Buddha imprints. In general, Enlightenment of Samsara. -

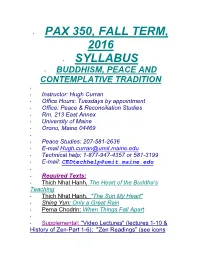

Pax 350, Fall Term, 2016 Syllabus

• PAX 350, FALL TERM, 2016 • SYLLABUS • BUDDHISM, PEACE AND CONTEMPLATIVE TRADITION • • Instructor: Hugh Curran • Office Hours: Tuesdays by appointment • Office: Peace & Reconciliation Studies • Rm. 213 East Annex • University of Maine • Orono, Maine 04469 • • Peace Studies: 207-581-2636 • E-mail [email protected] • Technical help: 1-877-947-4357 or 581-3199 • E-mail: [email protected] • • Required Texts: • Thich Nhat Hanh, The Heart of the Buddha’s Teaching • Thich Nhat Hanh, "The Sun My Heart" • Shing Yun: Only a Great Rain • Pema Chodrin: When Things Fall Apart • • Supplemental: “Video Lectures" (lectures 1-10 & History of Zen-Part 1-6); "Zen Readings” (see icons above lessons): Articles include: The Way of Zen; The Spirit of Zen; Mysticism; Sermons of a Buddhist Abbot ;Dharma Rain; • • Recommended: • Donald Lopez, “The Story of Buddhism” • Dalai Lama: How to Practice Thich Nhat Hanh:"Commentaries on the Heart Sutra" • • The UMA Bookstore 800 number is: 1-800-621- 0083 • The Fax number of the UMA Bookstore is: 1-800- 243-7338The UM Bookstore number is:1-207- 581- 1700 and e-mail at [email protected] • • Course Objective: • Course Objective: • This course is designed as an introduction to Buddhism, especially the practice of Zen (Ch'an). We will examine spiritual & ethical aspects including stories, sutras, ethical precepts, ecological issues, and how we can best embody the Way in our daily lives. • • University Policy: • In complying with the letter and spirit of applicable laws and in pursuing its own goals of pluralism, the University of Maine shall not discriminate on the grounds of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, national origin or citizenship status, age, disability, or veterans status in employment, education, and all other areas of the University. -

The Role of the Brahmavihāra in Psychotherapeutic Practice

THE ROLE OF THE BRAHMAVIHĀRA IN PSYCHOTHERAPEUTIC PRACTICE The following is an essay written early in 2006 for an MA-course in Buddhist Psychotherapy. It addresses some questions on the relevance and the relationship of a key aspect of Buddhist understanding and prac- tice (namely the Four Brahmavihàra) to the psychotherapeutic setting and, in particular, to their role in Core Process Psychotherapy. ekamantaṃ nisinno kho asibandhakaputto gāmaṇi bhagavantaṃ etadavoca || nanu bhante | bhagavā sabbapāṇabhūtahitānukampī viharatīti || evaṃ gāmaṇi | tathāgato sabbapāṇabhūtahitānukampī viharatīti || (S iv 314) Sitting down to one side the headman Asibandhakaputto addressed the Blessed One thus: »Does the Blessed One abide in compassion and care for the welfare of all sentient beings? – »Ideed, headman, it is so. The Tathāgata abides in compassion and care for the welfare of all sentient beings.« (Saṁyutta Nikāya S 42, 7) The role of the Brahmavihàra in Core Process Psychotherapy – Akincano M. Weber 2006 – 1 – INTRODUCTION Core Process Psychotherapy is a contemplative Psychotherapy and refers explicitly to a Buddhist understanding of health and mind-development (bhàvanà). The following es- say is an attempt to understand the concept of the four Brahmavihàra, their place and function in Buddhist mind-training and to address the questions of how they inform and relate to Core Process Psychotherapy. In PART ONE the first segment of the topic will be contextualised. The teaching of the Four Brahmavihàra in their Indian background will be looked at in some detail and as- pects of the Buddhist teaching on mind-cultivation relevant to Core Process Psycho- therapy will be drawn from. In PART TWO I will be looking briefly at the Western concepts of presence, embodiment, holding environment, relational field and Source-Being-Self. -

A Buddhist Approach Based on Loving- Kindness: the Solution of the Conflict in Modern World

A BUDDHIST APPROACH BASED ON LOVING- KINDNESS: THE SOLUTION OF THE CONFLICT IN MODERN WORLD Venerable Neminda A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Buddhist Studies) Graduate School Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University C.E. 2019 A Buddhist Approach Based on Loving-kindness: The Solution of the Conflict in Modern World Venerable Neminda A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Buddhist Studies) Graduate School Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University C.E. 2019 (Copyright by Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University) Dissertation Title : A Buddhist Approach Based on Loving-Kindness: The Solution of the Conflict in Modern World Researcher : Venerable Neminda Degree : Doctor of Philosophy (Buddhist Studies) Dissertation Supervisory Committee : Phramaha Hansa Dhammahaso, Assoc. Prof. Dr., Pāḷi VI, B.A. (Philosophy), M.A. (Buddhist Studies), Ph.D. (Buddhist Studies) : Asst. Prof. Dr. Sanu Mahatthanadull, B.A. (Advertising) M.A. (Buddhist Studies), Ph.D. (Buddhist Studies) Date of Graduation : February/ 26/ 2019 Abstract The dissertation is a qualitative research. There are three objectives, namely:- 1) To explore the concept of conflict and its cause found in the Buddhist scriptures, 2) To investigate the concept of loving-kindness for solving the conflicts in suttas and the best practices applied by modern scholars 3) To present a Buddhist approach based on loving-kindness: The solution of the conflict in modern world. This finding shows the concept of conflicts and conflict resolution method in the Buddhist scriptures. The Buddhist resolution is the loving-kindness. These loving- kindness approaches provide the method, and integration theory of the Buddhist teachings, best practice of modern scholar method which is resolution method in the modern world. -

The Bodhisattva Ideal in Selected Buddhist

i THE BODHISATTVA IDEAL IN SELECTED BUDDHIST SCRIPTURES (ITS THEORETICAL & PRACTICAL EVOLUTION) YUAN Cl Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 2004 ProQuest Number: 10672873 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672873 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This thesis consists of seven chapters. It is designed to survey and analyse the teachings of the Bodhisattva ideal and its gradual development in selected Buddhist scriptures. The main issues relate to the evolution of the teachings of the Bodhisattva ideal. The Bodhisattva doctrine and practice are examined in six major stages. These stages correspond to the scholarly periodisation of Buddhist thought in India, namely (1) the Bodhisattva’s qualities and career in the early scriptures, (2) the debates concerning the Bodhisattva in the early schools, (3) the early Mahayana portrayal of the Bodhisattva and the acceptance of the six perfections, (4) the Bodhisattva doctrine in the earlier prajhaparamita-siltras\ (5) the Bodhisattva practices in the later prajnaparamita texts, and (6) the evolution of the six perfections (paramita) in a wide range of Mahayana texts. -

Vedanta and Buddhism Final Enlightenment in Early Buddhism Frank Hoffman, West Chester University

Welcome to the Nineteenth International Congress of Vedanta being held on the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth campus. It is very exciting to think that the Vedanta Congress now is being held in the land of the “Boston Brahmins” Thoreau, Emerson and Whitman. It is very heartening to note that a large number of scholars are regular attendees of the Vedanta Congress, several are coming from India. We wel- come them all and are committed to help them in any way we can, to make their stay in Dartmouth pleasant and memorable. Our most appreciative thanks are due to Rajiv Malhotra and the Infinity Foun- dation and Pandit Ramsamooj of 3 R's Foundation for their generous financial support for holding the conference. We are particularly grateful to Anthony Garro, Provost, and William Hogan, Dean of College of Arts and Sciences, University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth for his continuous support of the Center for Indic Studies. Our special thanks to Maureen Jennings, Center's Administrative Assistant and a number of faculty and students (especially Deepti Mehandru and Shwetha Bhat) who have worked hard in the planning and organization of this conference. Bal Ram Singh S.S. Rama Rao Pappu Nineteenth International Congress of Vedanta July 28-31, 2010 - Program NINETEENTH INTERNATIONAL CONGRESS OF VEDANTA PROGRAM WEDNESDAY, JULY 28, 2010 All sessions to be held in Woodland Commons 8:00 AM - 6:00 PM Conference Registration Desk Open – Woodland Commons Lobby 8:00 AM - 8:30 AM Social/Coffee/Tea – Woodland Commons Lobby 8:45 AM Invocation & Vedic Chanting 9:00 AM Benediction 9:10 AM Welcome Address, Dean William Hogan, College of Arts & Sciences, University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth 9:20 AM Introduction, Conference Directors - Bal Ram Singh, University of Massachusetts Dartmouth S. -

Comparative Analysis of the Philosophies of Enlightenment

ENLIGHTENMENTS: Towards a Comparative Analysis of the Philosophies of Enlightenment in Buddhist, Eastern and Western Thought and the Search for a Holistic Enlightenment Suitable for the Contemporary World © Thomas Clough Daffern (B.A. Hons D.Sc. Hon PGCE), Director, International Institute of Peace Studies and Global Philosophy SOAS Buddhist Conference for Dongguk University on Global Ecological problems and the Buddhist Perspective, Feb. 2005 INDEX 1. Enlightenments: why the plural ? Some introductory questions 2. European Classical enlightenments 3. Zoroastrian Enlightenments 4. Enlightenments in Judaism 5. Christian enlightenments 6. Islamic Enlightenments 7. Buddhist Enlightenments 8. Hindu Enlightenments 9. Chinese enlightenments 10. Shinto 11. Pagan and Neo-pagan enlightenments 12. Transpersonal enlightenment theory 13. Conclusions 1. Enlightenments: why the plural ? Some introductory questions A word first about the basic presuppositions underlying this paper. I wish to institute a semantic and linguistic reform into our discussion abut enlightenment both in the academic literature and in everyday speech. We are all used to talk of the nature of enlightenment; Buddhist and Hindu textbooks carry information on the nature of enlightenment, as do Western philosophical and historical texts, although here we more often talk of The Enlightenment, as a period of largely European originated intellectual history, running from approximately the 1680’s to an indeterminate time, but usually September 1914 is taken as cut off time. This paper -

The Causes of Pain and the Yogic Prescriptions by Linda Munro from the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali

The Causes of Pain and the Yogic Prescriptions by Linda Munro from the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali Yoga is a spiritual discipline which was born out of the need to alleviate human suffering (duhkha). The ancient sages recognized that suffering sprouts from the mind and affects all levels of our human existence – physical, mental and spiritual. In fact suffering doesn‟t come from the outside; it is a response that we produce ourselves in our mind. This in a way can be reassuring because it means that we can find the strength within to do something about it! It is interesting to see the different reactions to suffering people have. Under similar circumstances two people can have entirely different responses. A simple example: two people in pretty much the same economical situations lose their jobs. One can take it as an opportunity to do something new and exciting; the other becomes depressed, unable to leave the house. Why? Why we suffer and can we do something? The ancient sages too, asked themselves: Why do we suffer? And can Pertinent Sutra: we do anything about it? The sage who compiled the Yoga Sutras, Patanjali gives us insight into the core reasons for our suffering and 2.2 “[This Yoga] (kriya yoga) has the purpose of yogic tools to apply in order to lessen our pain. It is inevitable in life that cultivating ecstasy (samādhi) and the purpose of thinning out the causes-of-affliction (kleshas). there will be pain and sorrow, however with yoga one can lessen causes and avoid future suffering! All translations by Georg Feuerstein with words in round brackets added by me ( ) to add clarity to my essay. -

Introduction to Buddhism Course Materials

INTRODUCTION TO BUDDHISM Readings and Materials Tushita Meditation Centre Dharamsala, India Tushita Meditation Centre is a member of the FPMT (Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition), an international network of more than 150 meditation centers and social service projects in over 40 countries under the spiritual guidance of Lama Zopa Rinpoche. More information about the FPMT can be found at: www.fpmt.org CARE OF DHARMA MATERIALS This booklet contains Dharma (teachings of the Buddha). All written materials containing Dharma teachings should be handled with respect as they contain the tools that lead to freedom and enlightenment. They should never be stepped over or placed directly on the floor or seat (where you sit or walk); a nice cloth or text table should be placed underneath them. It is best to keep all Dharma texts in a high clean place. They should be placed on the uppermost shelf of your bookcase or altar. Other objects, food, or even one’s mala should not be placed on top of Dharma texts. When traveling, Dharma texts should be packed in a way that they will not be damaged, and it is best if they are wrapped in a cloth or special Dharma book bag (available in Tushita’s library). PREPARATION OF THIS BOOKLET The material in this booklet was compiled using the ―Introductory Course Readings and Materials‖ booklet prepared by Ven. Sangye Khadro for introductory courses at Tushita, and includes several extensive excerpts from her book, How to Meditate. Ven. Tenzin Chogkyi made extensive additions and changes to this introductory course material in November 2008, while further material was added and some alterations made by Glen Svensson in July 2011, for this version. -

Sublime Abiding Places for the Heart

SUBLIME ABIDING PLACES FOR THE HEART adapted from a May 1999 workshop at Abhayagiri Buddhist Monastery with the Sati Center for Buddhist Studies THE BRAHMAVIHARAS ARE THE QUALITIES of loving-kindness, com- passion, sympathetic joy, and equanimity.What is often not sufficiently emphasized is that the brahmaviharas are fundamental to the Buddha’s teaching and practice. I shall begin with the chant called The Suffusion of the Divine Abidings.I find this chant very beautiful. It is the most frequent form in which the brahmaviharas are mentioned in the discourses of the Buddha. Here is the Divine Abidings chant: I will abide pervading one quarter with a mind imbued with loving-kindness; likewise the second, likewise the third, likewise the fourth; so above and below, around and everywhere; and to all as to myself. I will abide pervading the all-encompassing world with a mind imbued with loving-kindness; abundant, exalted, immeasurable, without hostility, and without ill will. The chant continues similarly with the other three qualities: I will abide pervading one quarter with a mind imbued with compassion.…I will abide pervading one quarter with a mind imbued with gladness.… 14 Ajahn Pasanno SUBLIME ABIDING PLACES FOR THE HEART 15 I will abide pervading one quarter with a mind equanimity. If I walk up and down, my walking is imbued with equanimity.… sublime; my standing, my sitting is sublime.This is what I mean when I say it is a sublime abiding place. Last February I was asked to be the spiritual advisor to a Thai man who was to be executed at San Quentin, and I spent the last few days So even the Buddha, a completely enlightened being, still directed until his death with him. -

Importance of the Religious Values in Family Development

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 21, Issue 7, Ver. 1 (July. 2016) PP 01-05 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Importance of the Religious Values in Family Development Dr. Pisal Anita Sambhaji, Assistant Professor, Bharati Vidyapeeth University, Social Science centre, Pune. Abstract: India is the different country in world. India is a religion country and almost all people believe in religious values and their influence on family development in India. Family values are the foundation of the children to share your family values and traditions with your children. Family is the extremely important component of India culture. Families are valued highly and are a part of an individual life until death. Traditional family values that all fall under the “love task” include all our relationship. Traditional family values usually include such as religion, marriage, communication, traditions, morals, holidays interactions with relatives. Often when people get married they take in their older relatives and other realties provider support of them. Many people don’t think about their family values until a crisis that forces them to make decision that may go against their beliefs. While they may have faced with the realization that something doesn’t quite fit in to what they believe in family values are important on many different levels of the family structure. Families with defined values are able to stand strong on their views despite other people effort to break through with opposing beliefs. He process of transmission of the socialization process empirical studies on adolescent fully activities of youth values are analyzed development of ethical principal founded in religious traditions, text, belief. -

An Analysis of Love Development in Buddhism(1)

Academic Services Journal Prince of Songkla University (2018), 29(1), 174-187 An Analysis of Love Development in Buddhism(1) Anchalee Piyapanyawong Department of Humanities, Faculty of Liberal Arts, Rajamongala University of Technology Thunyaburi Corresponding author [email protected] Received 19 December 2016 | Revised 25 April 2017 | Accepted 27 April 2017 | Published 1 April 2018 Abstract This article aims of analyzing an ordinary person’s way of love development in the four forms of love (Brahmavihara): Universal love (metta), compassion (karuna), sympathetic joy (mudita), and equanimity (upekkha). Buddhist thinkers propose their development in different three models, namely: 1) There is no cultivating step between the four forms of love; 2) There is a cultivating step from universal love to other three forms of love independently; and 3) There are cultivating steps from universal love to compassion, sympathetic joy, and equanimity respectively. The analysis discovered that the third model is the most possible way for an ordinary person to develop love because the other three forms of love are based on universal love and each step of development is different in its degrees of difficulty. As a result, the four forms of love develop as universal love purification. Keywords: love, universal love, compassion, sympathetic joy, equanimity, love development Introduction about by an attitude of hatred. Thus, creating love As we all know love is an influential factor in our is necessary for our happiness and the peace of the lives from the day we are born until the day we pass world as Thich Nhat Hanh (2007, p. 3), the Vietnamese away.