Brahmaviharas.” Leigh Brasington’S Website: 29 Nov 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism Key Terms Pairs

Pairs! Cut out the pairs and challenge your classmate to a game of pairs! There are a number of key terms each of which correspond to a teaching or belief. The key concepts are those that are underlined and the others are general words to help your understanding of the concepts. Can you figure them out? Practicing Doctrine of single-pointed impermanence – Non-injury to living meditation through which states nothing things; the doctrine of mindfulness of Anicca ever is but is always in Samatha Ahimsa non-violence. breathing in order to a state of becoming. calm the mind. ‘Foe Destroyer’. A person Phenomena arising who has destroyed all The Buddhist doctrine together in a mutually delusions through Anatta of no-self. Pratitya interdependent web of Arhat training on the spiritual cause and effect. path. They will never be reborn again in Samsara. A person who has Loving-kindness generated spontaneous meditation practiced bodhichitta but who Pain, suffering, disease Metta in order to ‘cultivate has not yet become a and disharmony. Bodhisattva Dukkha loving-kindness’ Buddha; delaying their Bhavana towards others. parinirvana in order to help mankind. Meditation practiced in (Skandhas – Sanskrit): Theravada Buddhism The four sublime The five aggregates involving states: metta, karuna, which make up the Brahmavihara Khandas Vipassana concentration on the mudita and upekkha. self, as we know it. body or its sensations. © WJEC CBAC LTD 2016 Pairs! A being who has completely abandoned Liberation and true Path to the cessation all delusions and their cessation of the cycle of suffering – the Buddha imprints. In general, Enlightenment of Samsara. -

Jichihan and the Restoration and Innovation of Buddhist Practice

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1999 26/1-2 Jichihan and the Restoration and Innovation of Buddhist Practice Marc Buijnsters The various developments in doctrinal thought and practice during the Insei and Kamakura periods remain one of the most intensively researched fields in the study of Japanese Buddhism. Two of these developments con cern the attempts to restore the observance of traditional Buddhist ethics, and the problem of how Pure La n d tenets could be inserted into the esoteric teaching. A pivotal role in both developments has been attributed to the late-Heian monk Jichihan, who was lauded by the renowned Kegon scholar- monk Gydnen as “the restorer of the traditional precepts ” and patriarch of Japanese Pure La n d Buddhism.,’ At first glance, available sources such as Jichihan’s biograpmes hardly seem to justify these praises. Several newly discovered texts and a more extensive use of various historical sources, however, should make it possible to provide us with a much more accurate and complete picture of Jichihan’s contribution to the restoration and innovation of Buddhist practice. Keywords: Jichihan — esoteric Pure Land thousfht — Buddhist reform — Buddhist precepts As was n o t unusual in the late Heian period, the retired Regent- Chancellor Fujiwara no Tadazane 藤 原 忠 実 (1078-1162) renounced the world at the age of sixty-three and received his first Buddnist ordi nation, thus entering religious life. At tms ceremony the priest Jichi han officiated as Teacher of the Precepts (kaishi 戒自帀;Kofukuji ryaku 興福寺略年代記,Hoen 6/10/2). Fujiwara no Yorinaga 藤原頼長 (1120-11^)0), Tadazane^ son who was to be remembered as “Ih e Wicked Minister of the Left” for his role in the Hogen Insurrection (115bハ occasionally mentions in his diary that he had the same Jichi han perform esoteric rituals in order to recover from a chronic ill ness, achieve longevity,and extinguish his sins (Taiki 台gd Koji 1/8/6, 2/2/22; Ten,y6 1/6/10). -

161: the Ten Pillars of Buddhism Transcription Taken from the Windhorse Publications Book of the Same Title FOREWORD As the Open

161: The Ten Pillars of Buddhism Transcription taken from the Windhorse Publications book of the same title FOREWORD As the opening passage of this book makes clear, the paper reproduced here was first delivered to a gathering of members of the Western Buddhist Order, in London, in April 1984. The occasion marked the celebration of the Order's sixteenth anniversary, and the theme of the paper was one of fundamental importance to all those present: the Ten Precepts. These Precepts are the ten ethical principles that Order members `receive' at the time of their ordination, and which they undertake subsequently to observe as a spiritually potent aspect of their everyday lives. The theme was therefore a very basic and seemingly down-to-earth one, but here, as he is wont to do, Sangharakshita demonstrated that no theme is so `basic' that it can be taken for granted. As a communication from the Enlightened mind, the various formulations and expressions of the Buddha's teaching can be turned to again and again; their freshness and relevance can never be exhausted. As he spoke, it was clear that Sangharakshita was addressing a far larger audience than that which was present at the time. The relevance of his material extended of course to those Order members, present and future, who could not be there on that occasion. But it reached out further than that, to the entire, wider `Buddhist world', and still further, to all those who, whether Buddhist or not, seek guidance and insights in their quest for ethical standards by which to live. -

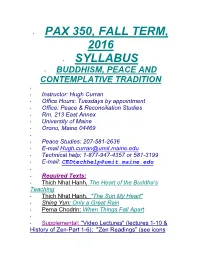

Pax 350, Fall Term, 2016 Syllabus

• PAX 350, FALL TERM, 2016 • SYLLABUS • BUDDHISM, PEACE AND CONTEMPLATIVE TRADITION • • Instructor: Hugh Curran • Office Hours: Tuesdays by appointment • Office: Peace & Reconciliation Studies • Rm. 213 East Annex • University of Maine • Orono, Maine 04469 • • Peace Studies: 207-581-2636 • E-mail [email protected] • Technical help: 1-877-947-4357 or 581-3199 • E-mail: [email protected] • • Required Texts: • Thich Nhat Hanh, The Heart of the Buddha’s Teaching • Thich Nhat Hanh, "The Sun My Heart" • Shing Yun: Only a Great Rain • Pema Chodrin: When Things Fall Apart • • Supplemental: “Video Lectures" (lectures 1-10 & History of Zen-Part 1-6); "Zen Readings” (see icons above lessons): Articles include: The Way of Zen; The Spirit of Zen; Mysticism; Sermons of a Buddhist Abbot ;Dharma Rain; • • Recommended: • Donald Lopez, “The Story of Buddhism” • Dalai Lama: How to Practice Thich Nhat Hanh:"Commentaries on the Heart Sutra" • • The UMA Bookstore 800 number is: 1-800-621- 0083 • The Fax number of the UMA Bookstore is: 1-800- 243-7338The UM Bookstore number is:1-207- 581- 1700 and e-mail at [email protected] • • Course Objective: • Course Objective: • This course is designed as an introduction to Buddhism, especially the practice of Zen (Ch'an). We will examine spiritual & ethical aspects including stories, sutras, ethical precepts, ecological issues, and how we can best embody the Way in our daily lives. • • University Policy: • In complying with the letter and spirit of applicable laws and in pursuing its own goals of pluralism, the University of Maine shall not discriminate on the grounds of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, national origin or citizenship status, age, disability, or veterans status in employment, education, and all other areas of the University. -

The Role of the Brahmavihāra in Psychotherapeutic Practice

THE ROLE OF THE BRAHMAVIHĀRA IN PSYCHOTHERAPEUTIC PRACTICE The following is an essay written early in 2006 for an MA-course in Buddhist Psychotherapy. It addresses some questions on the relevance and the relationship of a key aspect of Buddhist understanding and prac- tice (namely the Four Brahmavihàra) to the psychotherapeutic setting and, in particular, to their role in Core Process Psychotherapy. ekamantaṃ nisinno kho asibandhakaputto gāmaṇi bhagavantaṃ etadavoca || nanu bhante | bhagavā sabbapāṇabhūtahitānukampī viharatīti || evaṃ gāmaṇi | tathāgato sabbapāṇabhūtahitānukampī viharatīti || (S iv 314) Sitting down to one side the headman Asibandhakaputto addressed the Blessed One thus: »Does the Blessed One abide in compassion and care for the welfare of all sentient beings? – »Ideed, headman, it is so. The Tathāgata abides in compassion and care for the welfare of all sentient beings.« (Saṁyutta Nikāya S 42, 7) The role of the Brahmavihàra in Core Process Psychotherapy – Akincano M. Weber 2006 – 1 – INTRODUCTION Core Process Psychotherapy is a contemplative Psychotherapy and refers explicitly to a Buddhist understanding of health and mind-development (bhàvanà). The following es- say is an attempt to understand the concept of the four Brahmavihàra, their place and function in Buddhist mind-training and to address the questions of how they inform and relate to Core Process Psychotherapy. In PART ONE the first segment of the topic will be contextualised. The teaching of the Four Brahmavihàra in their Indian background will be looked at in some detail and as- pects of the Buddhist teaching on mind-cultivation relevant to Core Process Psycho- therapy will be drawn from. In PART TWO I will be looking briefly at the Western concepts of presence, embodiment, holding environment, relational field and Source-Being-Self. -

A Buddhist Approach Based on Loving- Kindness: the Solution of the Conflict in Modern World

A BUDDHIST APPROACH BASED ON LOVING- KINDNESS: THE SOLUTION OF THE CONFLICT IN MODERN WORLD Venerable Neminda A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Buddhist Studies) Graduate School Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University C.E. 2019 A Buddhist Approach Based on Loving-kindness: The Solution of the Conflict in Modern World Venerable Neminda A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Buddhist Studies) Graduate School Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University C.E. 2019 (Copyright by Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University) Dissertation Title : A Buddhist Approach Based on Loving-Kindness: The Solution of the Conflict in Modern World Researcher : Venerable Neminda Degree : Doctor of Philosophy (Buddhist Studies) Dissertation Supervisory Committee : Phramaha Hansa Dhammahaso, Assoc. Prof. Dr., Pāḷi VI, B.A. (Philosophy), M.A. (Buddhist Studies), Ph.D. (Buddhist Studies) : Asst. Prof. Dr. Sanu Mahatthanadull, B.A. (Advertising) M.A. (Buddhist Studies), Ph.D. (Buddhist Studies) Date of Graduation : February/ 26/ 2019 Abstract The dissertation is a qualitative research. There are three objectives, namely:- 1) To explore the concept of conflict and its cause found in the Buddhist scriptures, 2) To investigate the concept of loving-kindness for solving the conflicts in suttas and the best practices applied by modern scholars 3) To present a Buddhist approach based on loving-kindness: The solution of the conflict in modern world. This finding shows the concept of conflicts and conflict resolution method in the Buddhist scriptures. The Buddhist resolution is the loving-kindness. These loving- kindness approaches provide the method, and integration theory of the Buddhist teachings, best practice of modern scholar method which is resolution method in the modern world. -

Two Pure Land Sutras

The Smaller Pureland Sutra Thus did I hear Seven fine nets, seven rows of trees All of jewels made, sparkling and fine; Once the Buddha at Shravasti dwelt That's why they call it Perfect Bliss In the Jeta Anathapindika garden Together with a multitude of friars There are lakes of seven gems with One thousand two hundred and fifty Water of eightfold merit filled Who were arhats every one And beds of golden sand, As was recognised by all. To which descend on all four sides Gold, silver, beryl and crystal stairs. Amongst them... Shariputra the elder, Great Maudgalyayana, Pavilions and terraces rise above Maha-kashyapa, Gold, silver, beryl and crystal Maha-katyayana, Maha-kausthila, White coral, red pearl and agate gleaming; Revata, Shuddi-panthaka, And in the lakes lotus flowers Nanda, Ananda, Rahula, Large as chariot wheels Gavampati, Pindola Bhara-dvaja, Give forth their splendour Kalodayin, Maha-kapphina, Vakkula, Aniruddha, The blue ones radiate light so blue, and many other disciples The yellow yellow, each similarly great. Red red, white white and All most exquisite and finely fragrant. And, in addition, many bodhisattva mahasattvas... Oh Shariputra, the Land of Bliss Manjushri, prince of the Dharma, Like that is arrayed Ajita, Ganda-hastin, Nityo-dyukta, With many good qualities Together with all such as these And fine adornments. Even unto Shakra the king of devas With a vast assembly of celestials There is heavenly music Beyond reckoning. Spontaneously played And all the ground is strewn with gold. At that time Blossoms fall six times a day Buddha said to Shariputra From mandarava, “Millions of miles to the West from here, The divinest of flowers There lies a land called Perfect Bliss Where a Buddha, Amitayus by name In the morning light, Is even now the Dharma displaying. -

Kindness and Compassion Practice in Buddhist and Secular Contexts

Confluence: Adoption and Adaptation of Loving- Kindness and Compassion Practice in Buddhist and Secular Contexts Dawn P. Neal Graduate Student Graduate Theological Union 法鼓佛學學報第 16 期 頁 95-121(民國 104 年),新北市:法鼓文理學院 Dharma Drum Journal of Buddhist Studies, no. 16, pp. 95-121 (2015) New Taipei City: Dharma Drum Institute of Liberal Arts ISSN: 1996-8000 Abstract Contemporary Buddhists are adapting loving-kindness and compassion praxis. Using three vignettes, the author explores how the distinct practices of loving-kindness and compassion are being appropriated and altered both in Buddhist religious traditions, and in secular environments. This discussion examines the adaptation process from two perspectives. First, this article explores how three teachers, North American, Taiwanese, and Tibetan-North American respectively, adapt loving-kindness and compassion practices, and what purposes these adaptations serve in their contexts. Second, the author highlights some textual sources the teachers use when adapting or secularizing loving-kindness and compassion practices. Primary focus is on the Mettā Sutta and the Visuddhimagga, perhaps the most influential Theravāda compendium in contemporary Buddhism. The phrases and categories of loving-kindness praxis in the Visuddhimagga now appear nearly verbatim in teachings of secular compassion practice. This cross-fertilization occurs directly between Buddhist traditions as well. In the American example of Sojun Mel Weitsman, a foundational influence on modern Sōtō Zen Buddhism as developed at the Berkeley and San Francisco Zen centers, Weitsman presents his adaptation of the Mettā Sutta in response to his community’s request for greater address given to love and compassion. In Taiwan, Ven. Bhikṣuṇī Zinai of the eclectically influenced Luminary International Buddhist Society incorporates adaptation of both the Visuddhimagga and Mettā Sutta in a secular Compassionate Prenatal Education program, which addresses the needs of expectant mothers using loving-kindness practice. -

The Selfless Mind: Personality, Consciousness and Nirvāṇa In

PEI~SONALITY, CONSCIOUSNESS ANI) NII:tVANA IN EAI:tLY BUI)l)HISM PETER HARVEY THE SELFLESS MIND Personality, Consciousness and Nirv3J}.a in Early Buddhism Peter Harvey ~~ ~~~~!;"~~~~urzon LONDON AND NEW YORK First published in 1995 by Curzon Press Reprinted 2004 By RoutledgeCurzon 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Transferred to Digital Printing 2004 RoutledgeCurzon is an imprint ofthe Taylor & Francis Group © 1995 Peter Harvey Typeset in Times by Florencetype Ltd, Stoodleigh, Devon Printed and bound in Great Britain by Biddies Ltd, King's Lynn, Norfolk AU rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any fonn or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any infonnation storage or retrieval system, without pennission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress in Publication Data A catalog record for this book has been requested ISBN 0 7007 0337 3 (hbk) ISBN 0 7007 0338 I (pbk) Ye dhammd hetuppabhavti tesaf{l hetUf{l tathiigato aha Tesaii ca yo norodho evQf{lvtidi mahiisamaf10 ti (Vin.l.40) Those basic processes which proceed from a cause, Of these the tathiigata has told the cause, And that which is their stopping - The great wandering ascetic has such a teaching ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr Karel Werner, of Durham University (retired), for his encouragement and help in bringing this work to publication. I would also like to thank my wife Anne for her patience while I was undertaking the research on which this work is based. -

Hidden Realms and Pure Abodes: Central Asian Buddhism As Frontier Religion in the Literature of India, Nepal, and Tibet

Hidden Realms and Pure Abodes: Central Asian Buddhism as Frontier Religion in the Literature of India, Nepal, and Tibet Ronald M. Davidson Fairfield University The notable romantic interest in Silk Route studies in the last hundred years has spread far beyond the walls of academe, and is especially observed in the excessive world of journalism. In Japan, NHK (Japan Broadcasting Corporation) has produced a series of films whose images are extraordinary while their content remains superficial. The American Na- tional Geographical Society has followed suit in their own way, with some curious articles written by journalists and photographers. With the 2001 conflict in Afghanistan, American undergraduates have also begun to perceive Central Asia as a place of interest and excitement, an assessment that will not necessarily pay dividends in the support of serious scholar- ship. While Indian and Arab academic commentators on popular Western cultural movements want to read the lurid hand of Orientalism into such responses, I believe something more interesting is actually happening. Over the course of the past decade, I have often been struck by statements in medieval Buddhist literature from India, Nepal, and Tibet, statements that depict areas of Central Asia and the Silk Route in similarly exotic tones. Whether it is a land of secret knowledge or mystery, of danger and romance, or a land of opportunity and spirituality, the willingness of Indians, Nepalese, and Tibetans to entertain and accept fabulous descrip- tions of the domains wherein silk commerce and Buddhism existed for approximately a millennium is an interesting fact. More to the point, for the Buddhist traditions found in classical and medieval India and Tibet, there has been no area comparable to Central Asia for its combination of intellec- tual, ritual, mythic, and social impact. -

The Pratītyasamutpādagātha and Its Role in the Medieval Cult of the Relics

THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BUDDHIST STUDIES EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Roger Jackson Dept. oj Religion Carleton College Northfield, MN 55057 USA EDITORS Peter N. Gregory Ernst Steinkellner University of Illinois University of Vienna Urbana-Champaign, Illinois, USA Wien, Austria Alexander W. Macdonald Jikido Takasaki Universite de Paris X University of Tokyo Nanterre, France Tokyo, Japan Steven Collins Robert Thurman Concordia University Columbia University Montreal, Canada New York, New York, USA Volume 14 1991 Number 1 CONTENTS I. ARTICLES 1. The Pratityasamutpadagathd and Its Role in the Medieval Cult of the Relics, by Daniel Boucher 1 2. Notes on the Devotional Uses and Symbolic Functions of Sutra Texts as Depicted in Early Chinese Buddhist Miracle Tales and Hagiographies, by Robert F. Campany 28 3. A Source Analysis of the Ruijing lu ("Records of Miraculous Scriptures"), by Koichi Shinohara 73 4. Pudgalavada in Tibet? Assertions of Substantially Existent Selves in the Writings of Tsong-kha-pa and His Followers, by Joe Bransford Wilson 155 II. BOOK REVIEWS 1. The Dawn of Chinese Pure Land Buddhist Doctrine: Ching-ying Hui-yiian's Commentary on the Visualization Sutra, by Kenneth K. Tanaka (Allan A. Andrews) 181 2. Three Recent Collections: The Buddhist Heritage, ed. Tadeusz Skorupski; Chinese Buddhist Apocrypha, ed. Robert E. Buswell, Jr.; and Reflections on Tibetan Culture, ed. Lawrence Epstein and Richard Sherburne (Roger Jackson) 191 LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS 195 The Pratityasamutpddagathd and Its Role in the Medieval Cult of the Relics by Daniel Boucher I. Introduction Over the past one hundred and fifty years, thousands of clay seals, miniature stupas, and images inscribed with the famous "Buddhist creed" (the ye dharmd hetuprabhava.. -

The Bodhisattva Ideal in Selected Buddhist

i THE BODHISATTVA IDEAL IN SELECTED BUDDHIST SCRIPTURES (ITS THEORETICAL & PRACTICAL EVOLUTION) YUAN Cl Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 2004 ProQuest Number: 10672873 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672873 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This thesis consists of seven chapters. It is designed to survey and analyse the teachings of the Bodhisattva ideal and its gradual development in selected Buddhist scriptures. The main issues relate to the evolution of the teachings of the Bodhisattva ideal. The Bodhisattva doctrine and practice are examined in six major stages. These stages correspond to the scholarly periodisation of Buddhist thought in India, namely (1) the Bodhisattva’s qualities and career in the early scriptures, (2) the debates concerning the Bodhisattva in the early schools, (3) the early Mahayana portrayal of the Bodhisattva and the acceptance of the six perfections, (4) the Bodhisattva doctrine in the earlier prajhaparamita-siltras\ (5) the Bodhisattva practices in the later prajnaparamita texts, and (6) the evolution of the six perfections (paramita) in a wide range of Mahayana texts.