Introduction to Buddhism Course Materials

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism Key Terms Pairs

Pairs! Cut out the pairs and challenge your classmate to a game of pairs! There are a number of key terms each of which correspond to a teaching or belief. The key concepts are those that are underlined and the others are general words to help your understanding of the concepts. Can you figure them out? Practicing Doctrine of single-pointed impermanence – Non-injury to living meditation through which states nothing things; the doctrine of mindfulness of Anicca ever is but is always in Samatha Ahimsa non-violence. breathing in order to a state of becoming. calm the mind. ‘Foe Destroyer’. A person Phenomena arising who has destroyed all The Buddhist doctrine together in a mutually delusions through Anatta of no-self. Pratitya interdependent web of Arhat training on the spiritual cause and effect. path. They will never be reborn again in Samsara. A person who has Loving-kindness generated spontaneous meditation practiced bodhichitta but who Pain, suffering, disease Metta in order to ‘cultivate has not yet become a and disharmony. Bodhisattva Dukkha loving-kindness’ Buddha; delaying their Bhavana towards others. parinirvana in order to help mankind. Meditation practiced in (Skandhas – Sanskrit): Theravada Buddhism The four sublime The five aggregates involving states: metta, karuna, which make up the Brahmavihara Khandas Vipassana concentration on the mudita and upekkha. self, as we know it. body or its sensations. © WJEC CBAC LTD 2016 Pairs! A being who has completely abandoned Liberation and true Path to the cessation all delusions and their cessation of the cycle of suffering – the Buddha imprints. In general, Enlightenment of Samsara. -

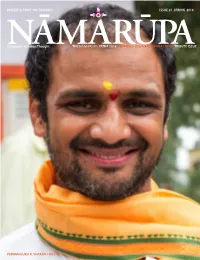

Issue 21 Spring 2016 Digital & Print-On-Demand

DIGITAL & PRINT-ON-DEMAND ISSUE 21 SPRING 2016 NĀMARŪPACategories of Indian Thought THE NĀMARŪPA YATRA 2015 ASHTANGA YOGA SADHANA RETREAT TRIBUTE ISSUE PARAMAGURU R. SHARATH JOIS NĀMARŪPA ISSUE 21 SPRING 2016 Categories of Indian Thought THE NĀMARŪPA YATRA 2015 ASHTANGA YOGA SADHANA RETREAT TRIBUTE ISSUE Publishers & Founding Editors Robert Moses & Eddie Stern NĀMARŪPA YATRA 2015 4 THE POSTER & ROUTE MAP Advisors Dr. Robert E. Svoboda GROUP PHOTOGRAPH 6 NĀMARŪPA YATRA 2015 Meenakshi Moses PALLAVI SHARMA DUFFY 8 WELCOME SPEECH Jocelyne Stern During the Folk Festival at Editors Vishnudevananda Tapovan Kuti Eddie Stern & Meenakshi Moses Design & Production Robert Moses PARAMAGURU 10 CONFERENCES AT TAPOVAN KUTI Proofreading & Transcription R. SHARATH JOIS Transcriptions of talks after class Meenakshi Moses Melanie Parker ROBERT MOSES 28 PHOTO ESSAY Megan Weaver Ashtanga Yoga Sadhana Retreat October 2015 Meneka Siddhu Seetharaman Website www.namarupa.org by BRAHMA VIDYA PEETH Roberto Maiocchi & Robert Moses ACHARYAS 48 TALKS ON INDIAN CULTURE All photographs in Issue 21 SWAMI SHARVANANDA Robert Moses except where noted. SWAMI HARIBRAMENDRANANDA Cover: R. Sharath Jois at Vishwanath Mandir, Uttarkashi, Himalayas. SWAMI MITRANANDA 58 NAVARATRI Back cover: Welcome sign at Kashi Vishwanath Mandir, Uttarkashi. SUAN LIN 62 FINE ART PHOTOGRAPHS October 13, 2015. Analog photography during Yatra 2015 SATYA MOSES DAŚĀVATĀRA ILLUSTRATIONS NĀMARŪPA Categories of Indian Thought, established in 2003, honors the many systems of knowledge, prac- tical and theoretical, that have origi- nated in India. Passed down through अ आ इ ई उ ऊ the ages, these systems have left tracks, a ā i ī u ū paths already traveled that can guide ए ऐ ओ औ us back to the Self—the source of all e ai o au names NĀMA and forms RŪPA. -

The Foundation of All Good Qualities by Lama Tsongkhapa

PRACTICE The Foundation of All Good Qualities By Lama Tsongkhapa In the 11th century, Tibet was blessed by the arrival of capacities of varying practitioners — small, medium, and the Indian Buddhist master Lama Atisha. Motivated to pres- great — which organize practices and meditations on the ent an organized summary of the sutra teachings, Atisha path into gradual stages. composed a short text entitled, The Lamp of the Path. Three Lama Tsongkhapa's famous prayer, The Foundation of hundred years later, Lama Tsongkhapa expanded upon this All Good Qualities, is the most concise and stirring outline text with his opus The Great Exposition on the Stages of the available of the Lam-Rim teachings. In only fourteen stanzas, Path to Enlightenment (Lamrim Chenmo). The often referred Tsongkhapa offers us a prayer that covers the entire graduated to "Lam-Rim teachings" are taken from this seminal text. path to enlightenment, short enough to recite every day, The teachings are presented in three scopes according to the profound enough to study for a lifetime. The foundation of all good qualities is the kind and venerable guru; I will not achieve enlightenment. Correct devotion to him is the root of the path. With my clear recognition of this. By clearly seeing this and applying great effort, Please bless me to practice the bodhisattva vows with great energy. Please bless me to rely upon him with great respect. Once I have pacified distractions to wrong objects Understanding that the precious freedom of this rebirth is found And correctly analyzed the meaning of reality, only once. -

The Meaning of “Zen”

MATSUMOTO SHIRÕ The Meaning of “Zen” MATSUMOTO Shirõ N THIS ESSAY I WOULD like to offer a brief explanation of my views concerning the meaning of “Zen.” The expression “Zen thought” is not used very widely among Buddhist scholars in Japan, but for Imy purposes here I would like to adopt it with the broad meaning of “a way of thinking that emphasizes the importance or centrality of zen prac- tice.”1 The development of “Ch’an” schools in China is the most obvious example of how much a part of the history of Buddhism this way of think- ing has been. But just what is this “zen” around which such a long tradition of thought has revolved? Etymologically, the Chinese character ch’an 7 (Jpn., zen) is thought to be the transliteration of the Sanskrit jh„na or jh„n, a colloquial form of the term dhy„na.2 The Chinese characters Ï (³xed concentration) and ÂR (quiet deliberation) were also used to translate this term. Buddhist scholars in Japan most often used the com- pound 7Ï (zenjõ), a combination of transliteration and translation. Here I will stick with the simpler, more direct transliteration “zen” and the original Sanskrit term dhy„na itself. Dhy„na and the synonymous sam„dhi (concentration), are terms that have been used in India since ancient times. It is well known that the terms dhy„na and sam„hita (entering sam„dhi) appear already in Upani- ¤adic texts that predate the origins of Buddhism.3 The substantive dhy„na derives from the verbal root dhyai, and originally meant deliberation, mature reµection, deep thinking, or meditation. -

And Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 The Raven and the Serpent: "The Great All- Pervading R#hula" Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet Cameron Bailey Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE RAVEN AND THE SERPENT: “THE GREAT ALL-PERVADING RHULA” AND DMONIC BUDDHISM IN INDIA AND TIBET By CAMERON BAILEY A Thesis submitted to the Department of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Religion Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Cameron Bailey defended this thesis on April 2, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Bryan Cuevas Professor Directing Thesis Jimmy Yu Committee Member Kathleen Erndl Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For my parents iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank, first and foremost, my adviser Dr. Bryan Cuevas who has guided me through the process of writing this thesis, and introduced me to most of the sources used in it. My growth as a scholar is almost entirely due to his influence. I would also like to thank Dr. Jimmy Yu, Dr. Kathleen Erndl, and Dr. Joseph Hellweg. If there is anything worthwhile in this work, it is undoubtedly due to their instruction. I also wish to thank my former undergraduate advisor at Indiana University, Dr. Richard Nance, who inspired me to become a scholar of Buddhism. -

Imagining Ritual and Cultic Practice in Koguryŏ Buddhism

International Journal of Korean History (Vol.19 No.2, Aug. 2014) 169 Imagining Ritual and Cultic Practice in Koguryŏ Buddhism Richard D. McBride II* Introduction The Koguryŏ émigré and Buddhist monk Hyeryang was named Bud- dhist overseer by Silla king Chinhŭng (r. 540–576). Hyeryang instituted Buddhist ritual observances at the Silla court that would be, in continually evolving forms, performed at court in Silla and Koryŏ for eight hundred years. Sparse but tantalizing evidence remains of Koguryŏ’s Buddhist culture: tomb murals with Buddhist themes, brief notices recorded in the History of the Three Kingdoms (Samguk sagi 三國史記), a few inscrip- tions on Buddhist images believed by scholars to be of Koguryŏ prove- nance, and anecdotes in Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms (Samguk yusa 三國遺事) and other early Chinese and Japanese literary sources.1 Based on these limited proofs, some Korean scholars have imagined an advanced philosophical tradition that must have profoundly influenced * Associate Professor, Department of History, Brigham Young University-Hawai‘i 1 For a recent analysis of the sparse material in the Samguk sagi, see Kim Poksun 金福順, “4–5 segi Samguk sagi ŭi sŭngnyŏ mit sach’al” (Monks and monasteries of the fourth and fifth centuries in the Samguk sagi). Silla munhwa 新羅文化 38 (2011): 85–113; and Kim Poksun, “6 segi Samguk sagi Pulgyo kwallyŏn kisa chonŭi” 存疑 (Doubts on accounts related to Buddhism in the sixth century in the Samguk sagi), Silla munhwa 新羅文化 39 (2012): 63–87. 170 Imagining Ritual and Cultic Practice in Koguryŏ Buddhism the Sinitic Buddhist tradition as well as the emerging Buddhist culture of Silla.2 Western scholars, on the other hand, have lamented the dearth of literary, epigraphical, and archeological evidence of Buddhism in Kogu- ryŏ.3 Is it possible to reconstruct illustrations of the nature and characteris- tics of Buddhist ritual and devotional practice in the late Koguryŏ period? In this paper I will flesh out the characteristics of Buddhist ritual and devotional practice in Koguryŏ by reconstructing its Northeast Asian con- text. -

Training in Wisdom 6 Yogacara, the ‘Mind Only’ School: Buddha Nature, 5 Dharmas, 8 Kinds of Consciousness, 3 Svabhavas

Training in Wisdom 6 Yogacara, the ‘Mind Only’ School: Buddha Nature, 5 Dharmas, 8 kinds of Consciousness, 3 Svabhavas The Mind Only school evolved as a response to the possible nihilistic interpretation of the Madhyamaka school. The view “everything is mind” is conducive to the deep practice of meditational yogas. The “Tathagatagarbha”, the ‘Buddha Nature’ was derived from the experience of the Dharmakaya. Tathagata, the ‘Thus Come one’ is a name for a Buddha ( as is Sugata, the ‘Well gone One’ ). Garbha means ‘embryo’ and ‘womb’, the container and the contained, the seed of awakening . This potential to attain Buddhahood is said to be inherent in every sentient being but very often occluded by kleshas, ( ‘negative emotions’) and by cognitive obscurations, by wrong thinking. These defilements are adventitious, and can be removed by practicing Buddhist yogas and trainings in wisdom. Then the ‘Sun of the Dharma’ breaks through the clouds of obscurations, and shines out to all sentient beings, for great benefit to self and others. The 3 svabhavas, 3 kinds of essential nature, are unique to the mind only theory. They divide what is usually called ‘conventional truth’ into two: “Parakalpita” and “Paratantra”. Parakalpita refers to those phenomena of thinking or perception that have no basis in fact, like the water shimmering in a mirage. Usual examples are the horns of a rabbit and the fur of a turtle. Paratantra refers to those phenomena that come about due to cause and effect. They have a conventional actuality, but ultimately have no separate reality: they are empty. Everything is interconnected. -

The Dōgen Zenji´S 'Gakudō Yōjin-Shū' from a Theravada Perspective

The Dōgen Zenji´s ‘Gakudō Yōjin-shū’ from a Theravada Perspective Ricardo Sasaki Introduction Zen principles and concepts are often taken as mystical statements or poetical observations left for its adepts to use his/her “intuitions” and experience in order to understand them. Zen itself is presented as a teaching beyond scriptures, mysterious, transmitted from heart to heart, and impermeable to logic and reason. “A special transmission outside the teachings, that does not rely on words and letters,” is a well known statement attributed to its mythical founder, Bodhidharma. To know Zen one has to experience it directly, it is said. As Steven Heine and Dale S. Wright said, “The image of Zen as rejecting all forms of ordinary language is reinforced by a wide variety of legendary anecdotes about Zen masters who teach in bizarre nonlinguistic ways, such as silence, “shouting and hitting,” or other unusual behaviors. And when the masters do resort to language, they almost never use ordinary referential discourse. Instead they are thought to “point directly” to Zen awakening by paradoxical speech, nonsequiturs, or single words seemingly out of context. Moreover, a few Zen texts recount sacrilegious acts against the sacred canon itself, outrageous acts in which the Buddhist sutras are burned or ripped to shreds.” 1 Western people from a whole generation eager to free themselves from the religion of their families have searched for a spiritual path in which, they hoped, action could be done without having to be explained by logic. Many have founded in Zen a teaching where they could act and think freely as Zen was supposed to be beyond logic and do not be present in the texts - a path fundamentally based on experience, intuition, and immediate feeling. -

Com 23 Draft B

Community Issue 23 - Page 1 Autumn 2005 / 2548 The Upāsaka & Upāsikā Newsletter Issue No. 23 Dagoba at Mahintale Dagoba InIn thisthis issue.......issue....... InIn peoplepeople wewe trusttrust ?? TheThe Temple at Kosgoda The wisdom of the heartheart SicknessSickness——A Teacher AssistedAssisted DyingDying MakingMaking connectionsconnections beyond words BluebellBluebell WalkWalk Community Community Issue 23 - Page 2 In people we trust? Multiculturalism and community relations have been This is a thoroughly uncomfortable position to be in, as much in the news over recent months. The tragedy of anyone who has suffered from arbitrary discrimination can the London bombings and the spotlight this has attest. There is a feeling of helplessness that whatever one thrown on to what is called ‘the Moslem community’ says or does will be misinterpreted. There is a resentment has led me to reflect upon our own Buddhist that one is being treated unfairly. Actions that would pre- ‘community’. Interestingly, the name of this newslet- viously have been taken at face value are now suspected of ter is ‘Community’, and this was chosen in discussion having a hidden agenda in support of one’s group. In this between a number of us, because it reflected our wish situation, rumour and gossip tend to flourish, and attempts to create a supportive and inclusive network of Forest to adopt a more inclusive position may be regarded with Sangha Buddhist practitioners. suspicion, or misinterpreted to fit the stereotype. The AUA is predominantly supported by western Once a community has polarised, it can take a great deal converts to Buddhism. Some of those who frequent of work to re-establish trust. -

AyyaYeshe How To Be A

Ayya Yeshe How to Be a Light for Yourself and Others in Challenging Times Week One: “Establishing the Basis for Dharma Practice” September 4, 2017 Hi, I'm Ayya Yeshe. I'm an Australian Buddhist nun and I've been ordained 16 years. I'm the director of Bodhicitta Foundation, a charity for people in the slums of Central India, which has been running for over a decade. I'm also the founding abbess of a monastery in Australia, which we are currently raising funds for, called Khandro Ling Hermitage. I'm mainly from the Sakya tradition but I was ordained as a fully ordained nun by Thich Nhat Hanh, the Nobel Peace Prize nominee and Vietnamese Zen master. Today I would like to talk about The Seven Points of Mind Training by Geshe Chekawa, which is mainly from the Kagyu tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. It's actually quite a long and involved text but it's a wonderful introduction to Mahayana Buddhism. As we go through the text, I hope that I can make some of -

Relevance of Pali Tipinika Literature to Modern World

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL) Vol. 1, Issue 2, July 2013, 83-92 © Impact Journals RELEVANCE OF PALI TIPINIKA LITERATURE TO MODERN WORLD GYANADITYA SHAKYA Assistant Professor, School of Buddhist Studies & Civilization, Gautam Buddha University, Greater Noida, Gautam Buddha Nagar, Uttar Pradesh, India ABSTRACT Shakyamuni Gautam Buddha taught His Teachings as Dhamma & Vinaya. In his first sermon Dhammacakkapavattana-Sutta, after His enlightenment, He explained the middle path, which is the way to get peace, happiness, joy, wisdom, and salvation. The Buddha taught The Eightfold Path as a way to Nibbana (salvation). The Eightfold Path can be divided into morality, mental discipline, and wisdom. The collection of His Teachings is known as Pali Tipinika Literature, which is compiled into Pali (Magadha) language. It taught us how to be a nice and civilized human being. By practicing Sala (Morality), Samadhi (Mental Discipline), and Panna (Wisdom ), person can eradicate his all mental defilements. The whole theme of Tipinika explains how to be happy, and free from sufferings, and how to get Nibbana. The Pali Tipinika Literature tried to establish freedom, equality, and fraternity in this world. It shows the way of freedom of thinking. The most basic human rights are the right to life, freedom of worship, freedom of speech, freedom of thought and the right to be treated equally before the law. It suggests us not to follow anyone blindly. The Buddha opposed harmful and dangerous customs, so that this society would be full of happiness, and peace. It gives us same opportunity by providing human rights. -

As Mentioned in the Verse of the Foundation of All Good Qualities

Amitabha Buddhist Centre Second Basic Program – Module 9 Ornament for Clear Realization—Chapter Four The Eight Categories and Seventy Topics Transcript of the teachings by Khen Rinpoche Geshe Chonyi on The Eight Categories and Seventy Topics Root Text: The Eight Categories and Seventy Topics by Jetsün Chökyi Gyaltsen, translated by Jampa Gendun. Final draft October 2002, updated May 2011. © Jampa Gendun & FPMT, Inc. Lesson 8 5 July 2016 Exam Presentation for Module 8. The knower of paths (cont’d). Support for newly generating the Mahayana path of meditation. EXAM PRESENTATION FOR MODULE 8 You have heard about the four reliances. One of them says, "Do not rely on the person but rely on the doctrine.” In this context here, you should not pay so much attention to the person who is speaking. Rather you should focus on what is being said by the person. So pay attention to what is said, think about it and see whether you agree with it. (A student presents her chosen verses from Chapter Eight of Engaging in the Bodhisattva Deeds). ~~~~~~~~~~~~ THE KNOWER OF PATHS (CONT’D) Definiendum Definition Boundary No. of Topics topics (Seventy topics) Knower of Mahayana Mahayana 11 1. Limbs of knower of paths Paths superior’s clear path of 2. Knower of paths that knows realizer conjoined seeing hearers' paths with the wisdom through the 3. Knower of paths that knows directly realizing buddha solitary realizers' paths emptiness within ground 4. Mahayana path of seeing the continuum of 5. Function of the Mahayana path the person who of meditation possesses it.