A Brief Introduction to Buddhism and the Sakya Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Sakya Institute for Buddhist Studies Calendar.Xlsx

SAKYA INSTITUTE FOR BUDDHIST STUDIES 59 Church Street, Unit 3 Cambridge, MA 02138 sakya.net Registration is required by emaiL ([email protected]) Time Requirement Green Tara sadhana instruction and practice to accomplish mantra accumulation 26th; 7 - 9 pm Attendance on January 26th; Registration required. Continuing Vajrayogini sadhana practice to accomplish mantra accumulation and 23rd, 30th; 7 - 9 pm Vajrayogini Empowerment (Naropa Lineage); Registration required. instruction on Vajrayogini Self-Initiation practice Mangalam Yantra Yoga Level 6 25th; 7 - 9 pm Complete Yantra Level 5; Registration required. January Prajnaparamita Weekend Retreat 14th; 12 - 4 pm Open to public; $50; Registration required. Lion Headed Dakini Simhamukha Weekend Retreat 21st; 12 - 4 pm Open to public; $50; Registration required. Sitatapatra (White Umbrella) Weekend Retreat 28th; 12 - 4 pm Open to public; $50; Registration required. Meditation and Tara Puja 7th, 14th, 21st, 28th; 10 am - 12 pm Open to public Green Tara sadhana instruction and practice to accomplish mantra accumulation 2nd, 9th, 16th, 23rd; 7 - 9 pm Attendance on January 26th; Registration required. Continuing Vajrayogini sadhana practice to accomplish mantra accumulation and 6th, 13th, 20th, 27th; 7 - 9 pm Vajrayogini Empowerment (Naropa Lineage); Registration required. instruction on Vajrayogini Self-Initiation practice February Mangalam Yantra Yoga Level 6 1st, 8th, 15th, 22nd; 7 - 9 pm Complete Yantra Level 5; Registration required. Meditation and Tara Puja 4th, 11th, 18th, 25th; 10 am - 12 pm Open to public Green Tara sadhana instruction and practice to accomplish mantra accumulation 2nd, 9th, 16th, 23rd, 30th; 7 - 9 pm Attendance on January 26th; Registration required. Continuing Vajrayogini sadhana practice to accomplish mantra accumulation and 6th, 13th, 20th, 27th; 7 - 9 pm Vajrayogini Empowerment (Naropa Lineage); Registration required. -

Tibetan Buddhism

Tibetan Buddhism By C. Fred Smith Founders: Siddartha Gautama, the Buddha. The Tibetan form grew out of the teachings Kamalashila who defended traditional Indian Buddhism in Tibet against the Chinese form. Date: Founded between 600 and 400 BC in Northern India; Buddhism influenced Tibetan religion as early as AD 200, but only began to take on its Tibetan character after 792 AD. Its full expression as a Lamaist religion (one dependent on lamas or gurus to guide meditation) began in the 1200s, with the institution of the Dalai Lama in the 1600s. Key Words: Lama, Bon, Reincarnation, Dharma and Sangha BACKGROUND Tibetan Buddhism focuses on disciplined meditation to achieve enlightenment, which is the realization that life is impermanent, and the accompanying state of bliss. Its unusual character, different from other forms of Buddhism, lies in two facts. First, it traces its practices back to the earliest form of Buddhism from Northern India. Certain practices are similar to those of Hindu practitioners,1 and the meditative discipline is similar to that practiced in the first Buddhist Sanghas, or monastic communities. Second, its practices and “peculiar, even eerie character” are a result of its encounter with Bon, the older religion of Tibet, an animistic religion that emphasized shamans, rituals to invoke and appease spirits, and even sacrifices.2 Together, these produce a Buddhism centered on monks and monasteries that is “more colorful and supernatural”3 than other forms such as Zen.4 This form of Buddhism emphasizes the place of the lama, or teacher, who directs his charges in their meditation and ritual practices. -

Notes and Topics: Synopsis of Taranatha's History

SYNOPSIS OF TARANATHA'S HISTORY Synopsis of chapters I - XIII was published in Vol. V, NO.3. Diacritical marks are not used; a standard transcription is followed. MRT CHAPTER XIV Events of the time of Brahmana Rahula King Chandrapala was the ruler of Aparantaka. He gave offerings to the Chaityas and the Sangha. A friend of the king, Indradhruva wrote the Aindra-vyakarana. During the reign of Chandrapala, Acharya Brahmana Rahulabhadra came to Nalanda. He took ordination from Venerable Krishna and stu died the Sravakapitaka. Some state that he was ordained by Rahula prabha and that Krishna was his teacher. He learnt the Sutras and the Tantras of Mahayana and preached the Madhyamika doctrines. There were at that time eight Madhyamika teachers, viz., Bhadantas Rahula garbha, Ghanasa and others. The Tantras were divided into three sections, Kriya (rites and rituals), Charya (practices) and Yoga (medi tation). The Tantric texts were Guhyasamaja, Buddhasamayayoga and Mayajala. Bhadanta Srilabha of Kashmir was a Hinayaist and propagated the Sautrantika doctrines. At this time appeared in Saketa Bhikshu Maha virya and in Varanasi Vaibhashika Mahabhadanta Buddhadeva. There were four other Bhandanta Dharmatrata, Ghoshaka, Vasumitra and Bu dhadeva. This Dharmatrata should not be confused with the author of Udanavarga, Dharmatrata; similarly this Vasumitra with two other Vasumitras, one being thr author of the Sastra-prakarana and the other of the Samayabhedoparachanachakra. [Translated into English by J. Masuda in Asia Major 1] In the eastern countries Odivisa and Bengal appeared Mantrayana along with many Vidyadharas. One of them was Sri Saraha or Mahabrahmana Rahula Brahmachari. At that time were composed the Mahayana Sutras except the Satasahasrika Prajnaparamita. -

Yoga of Hevajra

Y oga of H evajra Practice of the Y uan K hans? Zoltán Cser Dharma Gate Buddhist College, Budapest Premise1 In the article of Shen Weirong we read2: “It has been widely accepted that Tibetan tantric Buddhism was very popular at the court of the great Mongol khans, yet little is known about the details of the Buddhist teaching that were taught and practiced enthusiastically in and outside the Mongol court of the Yuan dynasty. Due to the prevailing misconception that it was the tantric practice of Tibetan Buddhism, notoriously epitomized in the so-called Secret Teach ing of Supreme Bliss mimi daxile fa; esoteric samádhi of great joy), that caused the rapid downfall of the great Mongol-Yuan dynasty.” “Twenty years ago, I. Christopher Beckwith drew attention to a till then unnoticed Yuan-period collection in Chinese on Tibetan tantric Buddhist teachings. This col lection is called ^ fill? itt Dacheng yaodao miji, or Secret Collection of Works on the Quintessential Path of the Mahdyana. It includes at least 28 texts devoted3 to ÜtH daoguo, or lam ‘bras (the path and fruit) teaching, which are particularly fa voured by the Sa skya pa sect, and to da shouyin, or Mahdmudra. According to the publisher’s preface, this collection became a basic teachings text of the esoteric school in China, and from the Yuan through the Ming and Manchu Qing dynasties down to the present day it has been revered as a ‘sacred classic of the esoteric school.’ This collection attributed to Phagpa lama (1235-1280).” Let us see first of all the historical background, how the Khans were initiated into Hevajra tantra, one of the highest teaching in Buddhism. -

VT Module6 Lineage Text Major Schools of Tibetan Buddhism

THE MAJOR SCHOOLS OF TIBETAN BUDDHISM By Pema Khandro A BIRD’S EYE VIEW 1. NYINGMA LINEAGE a. Pema Khandro’s lineage. Literally means: ancient school or old school. Nyingmapas rely on the old tantras or the original interpretation of Tantra as it was given from Padmasambhava. b. Founded in 8th century by Padmasambhava, an Indian Yogi who synthesized the teachings of the Indian MahaSiddhas, the Buddhist Tantras, and Dzogchen. He gave this teaching (known as Vajrayana) in Tibet. c. Systemizes Buddhist philosophy and practice into 9 Yanas. The Inner Tantras (what Pema Khandro Rinpoche teaches primarily) are the last three. d. It is not a centralized hierarchy like the Sarma (new translation schools), which have a figure head similar to the Pope. Instead, the Nyingma tradition is de-centralized, with every Lama is the head of their own sangha. There are many different lineages within the Nyingma. e. A major characteristic of the Nyingma tradition is the emphasis in the Tibetan Yogi tradition – the Ngakpa tradition. However, once the Sarma translations set the tone for monasticism in Tibet, the Nyingmas also developed a monastic and institutionalized segment of the tradition. But many Nyingmas are Ngakpas or non-monastic practitioners. f. A major characteristic of the Nyingma tradition is that it is characterized by treasure revelations (gterma). These are visionary revelations of updated communications of the Vajrayana teachings. Ultimately treasure revelations are the same dharma principles but spoken in new ways, at new times and new places to new people. Because of these each treasure tradition is unique, this is the major reason behind the diversity within the Nyingma. -

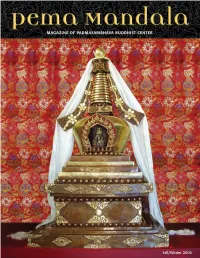

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1 Fall/Winter 2006 5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:03 PM Page 2 Volume 5, Fall/Winter 2006 features A Publication of 3 Letter from the Venerable Khenpos Padmasambhava Buddhist Center Nyingma Lineage of Tibetan Buddhism 4 New Home for Ancient Treasures A long-awaited reliquary stupa is now at home at Founding Directors Ven. Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche Padma Samye Ling, with precious relics inside. Ven. Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche 8 Starting to Practice Dream Yoga Rita Frizzell, Editor/Art Director Ani Lorraine, Contributing Editor More than merely resting, we can use the time we Beth Gongde, Copy Editor spend sleeping to truly benefit ourselves and others. Ann Helm, Teachings Editor Michael Nott, Advertising Director 13 Found in Translation Debra Jean Lambert, Administrative Assistant A student relates how she first met the Khenpos and Pema Mandala Office her experience translating Khenchen’s teachings on For subscriptions, change of address or Mipham Rinpoche. editorial submissions, please contact: Pema Mandala Magazine 1716A Linden Avenue 15 Ten Aspirations of a Bodhisattva Nashville, TN 37212 Translated for the 2006 Dzogchen Intensive. (615) 463-2374 • [email protected] 16 PBC Schedule for Fall 2006 / Winter 2007 Pema Mandala welcomes all contributions submitted for consideration. All accepted submissions will be edited appropriately 18 Namo Buddhaya, Namo Dharmaya, for publication in a magazine represent- Nama Sanghaya ing the Padmasambhava Buddhist Center. Please send submissions to the above A student reflects on a photograph and finds that it address. The deadline for the next issue is evokes more symbols than meet the eye. -

Buddhist Archeology in Mongolia: Zanabazar and the Géluk Diaspora Beyond Tibet

Buddhist Archeology in Mongolia: Zanabazar and the Géluk Diaspora beyond Tibet Uranchimeg Tsultemin, Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI) Uranchimeg, Tsultemin. 2019. “Buddhist Archeology in Mongolia: Zanabazar and the Géluk Dias- pora beyond Tibet.” Cross-Currents: East Asian History and Culture Review (e-journal) 31: 7–32. https://cross-currents.berkeley.edu/e-journal/issue-31/uranchimeg. Abstract This article discusses a Khalkha reincarnate ruler, the First Jebtsundampa Zanabazar, who is commonly believed to be a Géluk protagonist whose alliance with the Dalai and Panchen Lamas was crucial to the dissemination of Buddhism in Khalkha Mongolia. Za- nabazar’s Géluk affiliation, however, is a later Qing-Géluk construct to divert the initial Khalkha vision of him as a reincarnation of the Jonang historian Tāranātha (1575–1634). Whereas several scholars have discussed the political significance of Zanabazar’s rein- carnation based only on textual sources, this article takes an interdisciplinary approach to discuss, in addition to textual sources, visual records that include Zanabazar’s por- traits and current findings from an ongoing excavation of Zanabazar’s Saridag Monas- tery. Clay sculptures and Zanabazar’s own writings, heretofore little studied, suggest that Zanabazar’s open approach to sectarian affiliations and his vision, akin to Tsongkhapa’s, were inclusive of several traditions rather than being limited to a single one. Keywords: Zanabazar, Géluk school, Fifth Dalai Lama, Jebtsundampa, Khalkha, Mongo- lia, Dzungar Galdan Boshogtu, Saridag Monastery, archeology, excavation The First Jebtsundampa Zanabazar (1635–1723) was the most important protagonist in the later dissemination of Buddhism in Mongolia. Unlike the Mongol imperial period, when the sectarian alliance with the Sakya (Tib. -

Mindfulness and the Buddha's Noble Eightfold Path

Chapter 3 Mindfulness and the Buddha’s Noble Eightfold Path Malcolm Huxter 3.1 Introduction In the late 1970s, Kabat-Zinn, an immunologist, was on a Buddhist meditation retreat practicing mindfulness meditation. Inspired by the personal benefits, he de- veloped a strong intention to share these skills with those who would not normally attend retreats or wish to practice meditation. Kabat-Zinn developed and began con- ducting mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in 1979. He defined mindful- ness as, “the awareness that emerges through paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment to moment” (Kabat-Zinn 2003, p. 145). Since the establishment of MBSR, thousands of individuals have reduced psychological and physical suffering by attending these programs (see www.unmassmed.edu/cfm/mbsr/). Furthermore, the research into and popularity of mindfulness and mindfulness-based programs in medical and psychological settings has grown exponentially (Kabat-Zinn 2009). Kabat-Zinn (1990) deliberately detached the language and practice of mind- fulness from its Buddhist origins so that it would be more readily acceptable in Western health settings (Kabat-Zinn 1990). Despite a lack of consensus about the finer details (Singh et al. 2008), Kabat-Zinn’s operational definition of mindfulness remains possibly the most referred to in the field. Dozens of empirically validated mindfulness-based programs have emerged in the past three decades. However, the most acknowledged approaches include: MBSR (Kabat-Zinn 1990), dialectical behavior therapy (DBT; Linehan 1993), acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT; Hayes et al. 1999), and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT; Segal et al. -

And Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 The Raven and the Serpent: "The Great All- Pervading R#hula" Daemonic Buddhism in India and Tibet Cameron Bailey Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES THE RAVEN AND THE SERPENT: “THE GREAT ALL-PERVADING RHULA” AND DMONIC BUDDHISM IN INDIA AND TIBET By CAMERON BAILEY A Thesis submitted to the Department of Religion in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Religion Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Cameron Bailey defended this thesis on April 2, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Bryan Cuevas Professor Directing Thesis Jimmy Yu Committee Member Kathleen Erndl Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For my parents iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank, first and foremost, my adviser Dr. Bryan Cuevas who has guided me through the process of writing this thesis, and introduced me to most of the sources used in it. My growth as a scholar is almost entirely due to his influence. I would also like to thank Dr. Jimmy Yu, Dr. Kathleen Erndl, and Dr. Joseph Hellweg. If there is anything worthwhile in this work, it is undoubtedly due to their instruction. I also wish to thank my former undergraduate advisor at Indiana University, Dr. Richard Nance, who inspired me to become a scholar of Buddhism. -

Cúng Dường Mây Cam Lồ

Cúng Dường Mây Cam Lồ Một Sưu Tập Giáo Huấn Về Pháp Luyện Tâm Và Các Đề Tài Khác Choden Rinpoche Luận Giải TRI ÂN VÀ HỒI HƯỚNG Tác phẩm này đã được chuyển dịch và hiệu đính với sự gia trì của His Eminence Choden Rinpoche và chỉ giáo của Geshe Gyalten Kungka. Mọi sai sót là của người dịch. Mọi công đức có được xin hồi hướng cho sự giác ngộ của chúng sanh trong sáu cõi. Nguyện cầu tất cả các hữu tình có được sự dìu dắt của bậc giác ngộ để sớm thoát khỏi luân hồi. Cúng Dường Mây Cam Lồ: Một Sưu Tập Giáo Huấn Về Pháp Luyện Tâm Và Các Đề Tài Khác Luận Giải về Luyện Tâm Bát Đoạn của Geshe Langri Thangpa Dorje Senge Luận Giải về Thoát Khỏi Bốn Sự Bám Chấp của Jetsun Drakpa Gyaltsen Luận Giải về Tonglen, Hành Trì Cho và Nhận Luận Giải về Ba Điểm Tinh Yếu của Đường Tu Giác Ngộ của Tsongkhapa Luận Giải về Năm Điểm Chỉ Giáo của Pháp Chiết Xuất Tinh Chất của Đức Đạt Lai Lạt Ma đời thứ Hai Gendun Gyatso His Eminence Choden Rinpoche Gyalten Deying chuyển Việt ngữ Thanh Liên, Mai Tuyết Ánh hiệu đính SÁCH ẤN TỐNG – KHÔNG BÁN Awakening Vajra Publications 21 Banksia Crescent Churchill, Vic, Australia 3842 www.awakeningvajrapubs.org @Choden Rinpoche, Ian Coghlan, Voula Zarpani All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any forms or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photography, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system or technologies now known or later developed, without permission in writing from the publisher. -

The Dōgen Zenji´S 'Gakudō Yōjin-Shū' from a Theravada Perspective

The Dōgen Zenji´s ‘Gakudō Yōjin-shū’ from a Theravada Perspective Ricardo Sasaki Introduction Zen principles and concepts are often taken as mystical statements or poetical observations left for its adepts to use his/her “intuitions” and experience in order to understand them. Zen itself is presented as a teaching beyond scriptures, mysterious, transmitted from heart to heart, and impermeable to logic and reason. “A special transmission outside the teachings, that does not rely on words and letters,” is a well known statement attributed to its mythical founder, Bodhidharma. To know Zen one has to experience it directly, it is said. As Steven Heine and Dale S. Wright said, “The image of Zen as rejecting all forms of ordinary language is reinforced by a wide variety of legendary anecdotes about Zen masters who teach in bizarre nonlinguistic ways, such as silence, “shouting and hitting,” or other unusual behaviors. And when the masters do resort to language, they almost never use ordinary referential discourse. Instead they are thought to “point directly” to Zen awakening by paradoxical speech, nonsequiturs, or single words seemingly out of context. Moreover, a few Zen texts recount sacrilegious acts against the sacred canon itself, outrageous acts in which the Buddhist sutras are burned or ripped to shreds.” 1 Western people from a whole generation eager to free themselves from the religion of their families have searched for a spiritual path in which, they hoped, action could be done without having to be explained by logic. Many have founded in Zen a teaching where they could act and think freely as Zen was supposed to be beyond logic and do not be present in the texts - a path fundamentally based on experience, intuition, and immediate feeling. -

Zen and the Art of Storytelling Heesoon Bai & Avraham Cohen

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Simon Fraser University Institutional Repository Zen and the Art of Storytelling Heesoon Bai & Avraham Cohen Studies in Philosophy and Education An International Journal ISSN 0039-3746 Stud Philos Educ DOI 10.1007/s11217-014-9413-8 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Springer Science +Business Media Dordrecht. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be self- archived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your article, please use the accepted manuscript version for posting on your own website. You may further deposit the accepted manuscript version in any repository, provided it is only made publicly available 12 months after official publication or later and provided acknowledgement is given to the original source of publication and a link is inserted to the published article on Springer's website. The link must be accompanied by the following text: "The final publication is available at link.springer.com”. 1 23 Author's personal copy Stud Philos Educ DOI 10.1007/s11217-014-9413-8 Zen and the Art of Storytelling Heesoon Bai · Avraham Cohen © Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2014 Abstract This paper explores the contribution of Zen storytelling to moral education. First, an understanding of Zen practice, what it is and how it is achieved, is established. Second, the connection between Zen practice and ethics is shown in terms of the former’s ability to cultivate moral emotions and actions.