Compte-Rendu De Matthew Akester: Jamyang Khyentsé Wangpo's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1

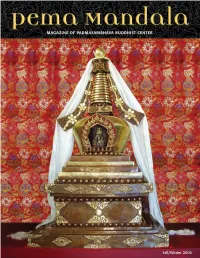

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1 Fall/Winter 2006 5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:03 PM Page 2 Volume 5, Fall/Winter 2006 features A Publication of 3 Letter from the Venerable Khenpos Padmasambhava Buddhist Center Nyingma Lineage of Tibetan Buddhism 4 New Home for Ancient Treasures A long-awaited reliquary stupa is now at home at Founding Directors Ven. Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche Padma Samye Ling, with precious relics inside. Ven. Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche 8 Starting to Practice Dream Yoga Rita Frizzell, Editor/Art Director Ani Lorraine, Contributing Editor More than merely resting, we can use the time we Beth Gongde, Copy Editor spend sleeping to truly benefit ourselves and others. Ann Helm, Teachings Editor Michael Nott, Advertising Director 13 Found in Translation Debra Jean Lambert, Administrative Assistant A student relates how she first met the Khenpos and Pema Mandala Office her experience translating Khenchen’s teachings on For subscriptions, change of address or Mipham Rinpoche. editorial submissions, please contact: Pema Mandala Magazine 1716A Linden Avenue 15 Ten Aspirations of a Bodhisattva Nashville, TN 37212 Translated for the 2006 Dzogchen Intensive. (615) 463-2374 • [email protected] 16 PBC Schedule for Fall 2006 / Winter 2007 Pema Mandala welcomes all contributions submitted for consideration. All accepted submissions will be edited appropriately 18 Namo Buddhaya, Namo Dharmaya, for publication in a magazine represent- Nama Sanghaya ing the Padmasambhava Buddhist Center. Please send submissions to the above A student reflects on a photograph and finds that it address. The deadline for the next issue is evokes more symbols than meet the eye. -

Please Click This Link

5, rond -point du Vignoble SAKYA TSECHEN LING F-67520 KUTTOLSHEIM (FRANCE) INSTITUT EUROP ÉEN DE Téléphone : +33 (0)3 88 87 73 80 BOUDDHISME TIBÉTAIN Secrétariat : +33 (0)3 88 87 73 80 FONDATEUR : KHENCHEN GU ÉSH É SHÉRAB E-mail : [email protected] GYALTSEN AMIPA RINPOCHÉ Site web : http://sakyatsechenling.eu Kuttolsheim, December 1 st 2019 Seminars at SAKYA TSECHEN LING Kuttolsheim in 2020 24 - 26 January: Prayer Sampa Lhundrupma - Khenpo Tashi Sampa Lhundrupma, The Prayer to Guru Rinpoche That Spontaneously Fulfills All Wishes , is a prayer that forms the seventh chapter of Le'u Dünma, a terma revealed in the fourteenth century. It was given to the prince Mutri Tsenpo, the King of Gungthang, and son of King Trisong Detsen, by Padmasambhava as he was leaving for the land of the rakshasa demons in the southwest. Tulku Zangpo Drakpa revealed this famous and powerful prayer. 14 - 16 February: The 37 practices of Bodhisattvas, part II - Khenpo Tashi The mind training text, 37 Bodhisattva Practices , was written in Tibet in the fourteenth century by the Sakya master Togme Zangpo. Togme Zangpo was well known as being an actual Bodhisattva, and his text is studied by all of the various Tibetan traditions. It is in fact a great classic of Tibetan literature and for centuries has inspired many practitioners on the path of Mahayana, as it offers many concrete cues to integrate every experience of life in the spiritual path. 22 February: GUTOR & Mahakala day 16:00 Mahakala ritual with Gutor , a ritual to eliminate negativities accumulated during the past year and to build protection for the upcoming new Tibetan year. -

A Brief Introduction to Buddhism and the Sakya Tradition

A brief introduction to Buddhism and the Sakya tradition © 2016 Copyright © 2016 Chödung Karmo Translation Group www.chodungkarmo.org International Buddhist Academy Tinchuli–Boudha P.O. Box 23034 Kathmandu, Nepal www.internationalbuddhistacademy.org Contents Preface 5 1. Why Buddhism? 7 2. Buddhism 101 9 2.1. The basics of Buddhism 9 2.2. The Buddha, the Awakened One 12 2.3. His teaching: the Four Noble Truths 14 3. Tibetan Buddhism: compassion and skillful means 21 4. The Sakya tradition 25 4.1. A brief history 25 4.2. The teachings of the Sakya school 28 5. Appendices 35 5.1. A brief overview of different paths to awakening 35 5.2. Two short texts on Mahayana Mind Training 39 5.3. A mini-glossary of important terms 43 5.4. Some reference books 46 5 Preface This booklet is the first of what we hope will become a small series of introductory volumes on Buddhism in thought and practice. This volume was prepared by Christian Bernert, a member of the Chödung Karmo Translation Group, and is meant for interested newcomers with little or no background knowledge about Buddhism. It provides important information on the life of Buddha Shakyamuni, the founder of our tradition, and his teachings, and introduces the reader to the world of Tibetan Buddhism and the Sakya tradition in particular. It also includes the translation of two short yet profound texts on mind training characteristic of this school. We thank everyone for their contributions towards this publication, in particular Lama Rinchen Gyaltsen, Ven. Ngawang Tenzin, and Julia Stenzel for their comments and suggestions, Steven Rhodes for the editing, Cristina Vanza for the cover design, and the Khenchen Appey Foundation for its generous support. -

Melody of Dharma Remarks on the Essence of Buddhist Tantra H.H

Melody of Dharma Remarks on the Essence of Buddhist Tantra H.H. the Sakya Trizin and Khöndung A teaching by H.H. the Sakya Trizin Gyana Vajra Rinpoche in Europe Remembering Great Masters Khöndung Ratna Vajra Rinpoche in Mahasiddha Dombi Heruka Asia A Publication of the Office of Sakya Dolma Phodrang Dedicated to the Dharma Activities of September No.12 His Holiness the Sakya Trizin 2013 • CONTENTS 1 From the Editors 2 His Holiness the Sakya Trizin 2014 Programme 3 Lumbini 9 Remembering Great Masters 9 t.BIBTJEEIB%PNCJ)FSVLB 10 t5IF'PVS4ZMMBCMFTCZ.BIBTJEEIB%PNCJ)FSVLB 11 Remarks on the Essence of Buddhist Tantra o"UFBDIJOHCZ)JT)PMJOFTTUIF4BLZB5SJ[JO 18 Oral Instructions on the Practice of Guru Yoga (Part 4) o"UFBDIJOHCZ$IPHZF5SJDIFO3JOQPDIF 27 Eight Verses of Pith Instructions to Elucidate the True Nature of Mind o#Z4BLZB1BOEJUB 29 A Melody of Experience for Yeshe Dorje o#Z+FUTÊO%SBHQB(ZBMUTFO 35 A Brief Explanation of Gyalphur Drubjor 36 Dharma Activities 36 t)JT)PMJOFTTUIF4BLZB5SJ[JOBOE,IÄOEVOH(ZBOB7BKSB 3JOQPDIFJO&VSPQF 41 t)JT)PMJOFTTUIF4BLZB5SJ[JOJOUIF64"BOE4JOHBQPSF 53 t-BNESF3FUFBDIJOHTJO5BJXBO,IÄOEVOH3BUOB7BKSB 3JOQPDIF 60 t-BNESFJO4JOHBQPSF,IÄOEVOH3BUOB7BKSB3JOQPDIF 62 t,IÄOEVOH3BUOB7BKSB3JOQPDIFJO,BUINBOEVBOE4QJUJ 7BMMFZ 64 t4VNNFSBUUIF4BLZB$FOUSF Patrons: H.E. Gyalyum Chenmo Art Director/Designer: Chang Ming-Chuan H.E. Dagmo Kalden Dunkyi Sakya Photos: Cristina Vanza; Sakya Phuntsok Phodrang; Adam Boyer; H.E. Dagmo Sonam Palkyi Sakya Steven Lay; Jon Schmidt; Andrea López; Alison Domzalski Publisher: The O!ce of Sakya Dolma Phodrang Editing Team: Rosemarie Heimsheidt; Tsering Samdup; Ngawang Executive Editor: Ani Jamyang Wangmo Jungney Managing Editor: Patricia Donohue Cover Photo: Mahadevi Temple, Lumbini From The Editors We hope that each and every one of our readers has had an excellent summer, filled with joy and bene"cial activities, and we extend to all a hearty welcome to this new edition of Melody of Dharma. -

1 My Literature My Teachings Have Become Available in Your World As

My Literature My teachings have become available in your world as my treasure writings have been discovered and translated. Here are a few English works. Autobiographies: Mother of Knowledge,1983 Lady of the Lotus-Born, 1999 The Life and Visions of Yeshe Tsogyal: The Autobiography of the Great Wisdom Queen, 2017 My Treasure Writings: The Life and Liberation of Padmasambhava, 1978 The Lotus-Born: The Life Story of Padmasambhava, 1999 Treasures from Juniper Ridge: The Profound Instructions of Padmasambhava to the Dakini Yeshe Tsogyal, 2008 Dakini Teachings: Padmasambhava’s Advice to Yeshe Tsogyal, 1999 From the Depths of the Heart: Advice from Padmasambhava, 2004 Secondary Literature on the Enlightened Feminine and my Emanations: Women of Wisdom, Tsultrim Allione, 2000 Dakini's Warm Breath: The Feminine Principle in Tibetan Buddhism, Judith Simmer- Brown, 2001 Machik's Complete Explanation: Clarifying the Meaning of Chod, Sarah Harding, 2003 Women in Tibet, Janet Gyatso, 2005 Meeting the Great Bliss Queen: Buddhists, Feminists, and the Art of the Self, Anne Carolyn Klein, 1995 When a Woman Becomes a Religious Dynasty: The Samding Dorje Phagmo of Tibet, Hildegard Diemberger, 2014 Love and Liberation: Autobiographical Writings of the Tibetan Buddhist Visionary Sera Khandro, Sarah Jacoby, 2015 1 Love Letters from Golok: A Tantric Couple in Modern Tibet, Holly Gayley, 2017 Inseparable cross Lifetimes: The Lives and Love Letters of the Tibetan Visionaries Namtrul Rinpoche and Khandro Tare Lhamo, Holly Gayley, 2019 A Few Meditation Liturgies: Yumkha Dechen Gyalmo, Queen of Great Bliss from the Longchen Nyingthik, Heart- Essence of the Infinite Expanse, Jigme Lingpa Khandro Thukthik, Dakini Heart Essence, Collected Works of Dudjom, volume MA, pgs. -

Biography of Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche

Dharma Dhrishti — Spring 2009 Biography of Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche .E. Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche, Thubten Chökyi Gyamtso, was born in 1961 in Bhutan, recognized as the mind emanation of one of the greatest H Dzogchen masters of the his time Jamyang Khyentse Chökyi Lodro (1893‐ 1959). The Khyentse lineage, starting with the great Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo, has always been characterized by the vision of non‐sectarianism. Reflecting this tradition, H.E. Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche studied with teachers from all the four schools of Tibetan Buddhism. Rinpoche received empowerments and teachings from many of the greatest contemporary masters, including H.H. the Dalai Lama, H.H. the 16th Karmapa, H.H. Sakya Trizin, and his own grandfathers, H.H. Dudjom Rinpoche and Sönam Zangpo. His main guru was H.H. Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche. Rinpoche further studied with more than 25 great lamas from all four schools of Tibetan Buddhism. While still a teenager, Rinpoche was responsible for publishing many rare texts that were in danger of being lost entirely, and in the 1980s, began the restoration of Dzongsar Monastery in Tibet. He has established several colleges and retreat centres in India (in Bir and Chauntra) and in Bhutan. In accordance with the wishes of his teachers, Rinpoche has traveled and taught throughout the world, establishing dharma centres in Australia, Europe, North America, and Asia. In 1989, H.E. Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche founded Siddharthaʹs Intent, a worldwide association of buddhist centers, whose principal intention is preserving the Buddhist teachings as well as deepening the understanding and awareness of the many aspects of the Buddhist teachings across different cultures and traditions. -

Biographies of Dzogchen Masters ~

~ Biographies of Dzogchen Masters ~ Jigme Lingpa: A Guide to His Works It is hard to overstate the importance of Jigme Lingpa to the Nyingma tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. This itinerant yogi, along with Rongzom Mahapandita, Longchenpa, and-later-Mipham Rinpoche, are like four pillars of the tradition. He is considered the incarnation of both the great master Vimalamitra and the Dharma king Trisong Detsen. After becoming a monk, he had a vision of Mañjuśrīmitra which caused him to change his monks robes for the white shawl and long hair of a yogi. In his late twenties, he began a long retreat during which he experienced visions and discovered termas. A subsequent retreat a few years later was the container for multiple visions of Longchenpa, the result of which was the Longchen Nyingthig tradition of terma texts, sadhanas, prayers, and instructions. What many consider the best source for understanding Jigme Lingpa's relevance, and his milieu is Tulku Thondup Rinpoche's Masters of Meditation and Miracles: Lives of the Great Buddhist Masters of India and Tibet. While the biographical coverage of him only comprises about 18 pages, this work provides the clearest scope of the overall world of Jigme Lingpa, his line of incarnations, and the tradition and branches of teachings that stem from him. Here is Tulku Thondup Rinpoche's account of his revelation of the Longchen Nyingtik. "At twenty-eight, he discovered the extraordinary revelation of the Longchen Nyingthig cycle, the teachings of the Dharmakāya and Guru Rinpoche, as mind ter. In the evening of the twenty-fifth day of the tenth month of the Fire Ox year of the thirteenth Rabjung cycle (1757), he went to bed with an unbearable devotion to Guru Rinpoche in his heart; a stream of tears of sadness continuously wet his face because he was not 1 in Guru Rinpoche's presence, and unceasing words of prayers kept singing in his breath. -

The Guru Yoga of the Omniscient Lama Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo Called Cloud of Joy

The Guru Yoga of the omniscient Lama Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo called Cloud of Joy The first thing is taking refuge. The text says "From this time until the attainment of Enlightenment, I and all sentient beings go for refuge to the guru who incorporates all the jewels of refuge." From this time refers to 'from now on'. "Until the attainment of Enlightenment" refers to the Mahayana refuge: taking refuge until one attains Enlightenment. "To the guru who incorporates all the refuges" refers to the fact that the guru's body signifies the Arya Sangha, the noble ones who have realised voidness. His speech is the Dharma, and His mind is the actual Buddha refuge. So we take refuge in the Guru who incorporates all the three refuges. "All sentient beings and I take refuge" - this again refers to the Mahayana refuge in which we take refuge until all sentient beings attain Enlightenment. The next line is "I shall develop both the wishing and venture stages of Bodhicitta." The wishing to attain the state of Enlightenment for the sake of all sentient beings, and the venturing stage is actually entering into the practices which here means the specific practice of guru yoga with Lama Jamyang Khyentse Wangpo Rinpoche as inseparable from Manjushri. By developing Bodhicitta in this context we say that we wish to attain Enlightenment. Through these practices we actually will enter into this practice of guru yoga. This first verse of four lines incorporates both refuge and bodhicitta. The next line is the development of the Four Immeasurables. It says "May all beings be endowed with Happiness", which is the line of Immeasurable Love, and "May they be free from suffering" which is Immeasurable Compassion. -

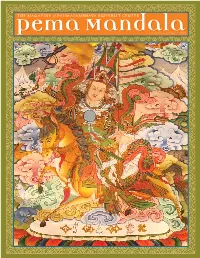

Pema Mandalamandalaspring~Summer 2015 in THIS ISSUE

THE MAGAZINE of PADMASAMBHAVA BUDDHIST CENTER PemaPema MandalaMandalaspring~summer 2015 IN THIS ISSUE 1 Letter from Venerable Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche 2 Lotus Land of Glorious Wisdom 4 Be Courageous 5 All Teachings Are on Refuge 6 Pemai Chiso Dharma Store 8 Chain of Golden Mountains 10 Everything is Mind 11 Gratitude for Our Wonderful Sangha 12 The Two Truths 13 Join PBC and Support Our Nuns and Monks GREG KRANZ GREG 14 2015 Summer/Fall Teaching Schedule Warm Greetings and Best Wishes to All Sangha and Friends, 16 Revealing the Buddha Within very spring we enjoy the opportunity to look happy, meaningful times we can all look forward to as 17 A Wealth of Translations by Dharma Samudra Publications back and celebrate another beautiful year over- we continue on this path of love and peace! flowing with many wonderful Dharma activi- 17 Living at PSL ties and events! I’m so thankful for everyone’s As we all know, again and again we must examine our E motivation, and reconnect to our true nature of love, continued support of PBC and your devotion to the 18 Great Purity: The Life and Teachings of Buddhadharma, the Nyingma lineage, and the legacy compassion, and wisdom and sincerely wish the best Rongzompa Mahapandita of our precious teacher, Venerable Khenchen Palden for everyone. This is the essence of Dharma, and the Sherab Rinpoche. sole purpose for our activities. We’ve all heard this many 24 The Unfolding Beauty of Padma Samye Ling times, but it remains true. The essence of Dharma is un- This past year we consecrated Palden Sherab Pema changing—it is great love and compassion that reaches 26 2014 Year in Review Ling in Jupiter, Florida, and enjoyed many retreats at out and supports limitless beings according to exactly PSL and our other PBC Centers—including special what’s helpful. -

Beyond Mind III: Further Steps to a Metatranspersonal Philosophy And

International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Volume 28 | Issue 2 Article 3 7-1-2009 Beyond Mind III: Further Steps to a Metatranspersonal Philosophy and Psychology (Continuation of the Discussion on the Three Best Known Transpersonal Paradigms, with a Focus on Washburn and Grof ) Elías Capriles University of the Andes Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies Part of the Philosophy Commons, Psychology Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Capriles, E. (2009). Capriles, E. (2009). Beyond mind III: Further steps to a metatranspersonal philosophy and psychology (Continuation of the discussion on the three best known transpersonal paradigms, with a focus on Washburn and Grof ). International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 28(2), 1–145.. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 28 (2). http://dx.doi.org/10.24972/ ijts.2009.28.2.1 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Transpersonal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Beyond Mind III: Further Steps to a Metatranspersonal Philosophy and Psychology (Continuation of the Discussion on the Three Best Known Transpersonal Paradigms, with a Focus on Washburn and Grof) Elías Capriles University of the Andes Mérida, Venezuela This paper gives continuity to the criticism, undertaken in two papers previously published in this journal, of transpersonal systems that fail to discriminate between nirvanic, samsaric, and neither- nirvanic-nor-samsaric transpersonal states, and which present the absolute sanity of Awakening as a dualistic, conceptually-tainted condition. -

Review of <I>The Life of Jamgon Kongtrul the Great</I> by Alexander

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 40 Number 1 Article 18 November 2020 Review of The Life of Jamgon Kongtrul the Great by Alexander Gardner Renée L. Ford Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation Ford, Renée L.. 2020. Review of The Life of Jamgon Kongtrul the Great by Alexander Gardner. HIMALAYA 40(1). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol40/iss1/18 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Review is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jamgon Kongtrul’s allegiances to particular people and places shines through the historical narrative Ford on The Life of Jamgon Kongtrul the Great. own contributions. Gardner attests Tibet surrounding Kham. One may that he approaches the diary with get lost in the fine details or settle a critical view, adjusting historical into beautifully written historical dates for accuracy and weeding non-fiction, which at times reads like through Kongtrul’s writing, which a screenplay. exposes his views and concerns In bringing Jamgon Kongtrul’s for others’ opinions about him (p. story to life and the West, Gardner XI). The autobiography is then garnishes the biography with detailed framed within a larger historical explanations of Buddhist topics. -

A Newsletter of Siddhartha's Intent

MARCH 2004 A NEWSLETTER OF SIDDHARTHA’S INTENT IN THIS ISSUE • VIEW, MEDITATION, ACTION • INTERVIEW WITH BERU KHYENTSE RINPOCHE • NORTHERN TREASURES • WHITE LOTUS - REACHING OUT FURTHER • THE NUNS OF KHACHOE GHAKYIL LING INTERVIEW BERU KHYENTSE RINPOCHE (Photo Ross Smith) Beru Khyentse Rinpoche Rinpoche, you were recognised by His Holiness the corals and turquoises. This is an example of what is called sixteenth Karmapa, were enthroned by him and received rangjung or self-arising manifestation. The Karmapa was many teachings from him. Could you say something a real Buddha. about his qualities? After you were enthroned, the Chinese invaded Tibet and you The Karmapa is like Buddha, not an ordinary human led your monks and lay disciples out of Tibet. Could you say a being. He is very great; he knows everything, the future little about that? and past lives. When he meditates, he can see everything. He recognised many, many tulkus, not in an ordinary way Yes. We left in early 1958. In 1959 the Chinese destroyed but in a very special way. He could see the exact place Lhasa and many monasteries. The fighting had started in where the lama was born, his parents, the distance and parts of eastern Tibet, around 1958, but it had not yet direction of how to locate that place, everything. become so bad. However, both the Karmapa and myself Sometimes he would just tell his secretary to write down had done mo (divinations) and those indicated that it these directions; sometimes, without being requested to would be better if we left Tibet. So, officially, we got do so, he would relate all the details of where a lama was permission from the local government to go on reborn.