Bhaga Vad-Gita

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dharma. India World...1.Rtf

DHARMA, INDIA AND THE WORLD ORDER TWENTY-ONE ESSAYS i ii DHARMA, INDIA AND THE WORLD ORDER TWENTY-ONE ESSAYS CHATURVEDI BADRINATH iii Copyright 1993 by Chaturvedi Badrinath First published 1993 by Pahl-Rugenstein and Saint Andrew Press. Pahl-Rugenstein Verlag Nachfolger GmbH BreiteStr.47 D-53111 Bonn Tel (0228) 63 23 06 Fax (0228) 63 49 68 Bundesrepublik Deutschland ISBN 3-89144-179-7 Saint Andrew Press 121 George Street Edinburgh EH2 4YN Scotland, UK Tel (031) 22 55 72 2 Fax (031) 22 03 113 ISBN 0-86513-172-8 Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Badrinath, Chaturvedi: Dharma, India, and the world order: twenty-one essays Chaturvedi Badrinath. - Edinburgh: Saint Andrew Press; Bonn: Pahl-Rugenstein, 1993 ISBN 3-89144-179-7 (Pahl-Rugenstein) ISBN 0-86153-172-8 (Saint Andrew Press) British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data: A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Typeset by Tulika Print Communication Services Pvt. Ltd. C-20, Qutab Institutional Area, New Delhi 110016 Printed in Hungary by Interpress iv To Bishop Lesslie Newbigin To whose friendship I owe much v vi CONTENTS Foreword ix Preface xv Acknowledgements xvii To the Reader xxv An Outline of the Inquiry and Arguments in the Twenty-one Essays 3 Twenty-one Essays 1 Hindus and Hinduism: Wrong Labels Given By Foreigners 19 2 Search for Dharma: Problems Stemming from Travesties 24 3 Understanding India: Key to Reform of Society 29 4 Limits to Political Power: Traditional Indian Precepts 34 5 Dharma is not 'Religion': Misconception Has to Be -

Invaluable Books of Brahmvidya

INVALUABLE BOOKS OF BRAHMVIDYA VACHANAMRUT AND SWAMI NI VAATO 1 Table of Contents PART 1 - BRAHMVIDYA ......................................................................................................... 6 1.1 The capacity of the human-brain to learn several kinds of knowledge ............................................... 6 1.2 The importance of Brahmvidya (Knowledge of atma) .......................................................................... 7 1.3 The Imporance and the necessity of Brahmvidya .................................................................................. 8 PART 2 - VACHANAMRUT…………..…………………………………...………..…………14 2.1 The aspects of Vachanamrut and the subjects explained therein ....................................................... 15 2.1.1 The aspects of Vachanamrut ......................................................................................................... 15 2.1.2 The topics covered in the Vachanamrut are spiritual, not mundane or worldly………………………………………………………………..………………16 2.2 Essence, secrets, and principle of all the scriptures in Vachanamrut ......................................... 18 2.3 Opinions About The Vachanamrut ................................................................................................. 21 2.3.1 The opinions of the Gunatit Gurus .............................................................................................. 21 2.3.2 The opinions of prominent learned personalities ....................................................................... 22 2.4 The -

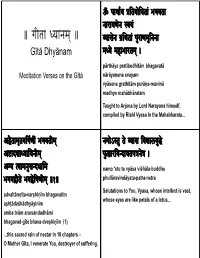

Microsoft Powerpoint

ॐ पाथाय ितबाधताे भगवता नारायणने वय ꠱ गीतॎ यॎनम् ꠱ यासेन थता पराणमिननापराणमु ुिनना Gītā Dhyānam मये महाभारतम् ꠰ pārthāya pratibodhitām bhagavatā Meditation Verses on the Gītā nārāyaṇena svayam vyāsena grathitām purāṇa-muninā madhyemahābhāratam Taught to Arjuna by Lord Narayana himself, compiled by Rishi Vyasa in the Mahabharata... अैतामतवषृ णी भगवतीम् नमाऽते त े यास वशालबु े अादशायाीयनीम् फु ारवदायतपन꠰ेे अब वामनसदधामवामनसदधामु namo 'stu te vyāsa viśhāla-buddhe phullāravindāyata-patra-netra भगवत े भवभवषणीमेषणीम् ꠱१꠱ Salutations to You, Vyyasa, whose intellect is vast, advaitāmṛita-varṣhiṇīm bhagavatīm whose eyes are like petals of a lotus... aṣhṭādaśhādhyāyinīm amba tvām anusandadhāmi bhagavad-gīte bhava-dveṣhiṇīm (1) ...this sacred rain of nectar in 18 chapters – O Mother Gita, I venerate You, destroyer of suffering. येन वया भारततलपै ूण पपारजाताय तावे े कपाणयै े꠰ वालता ेे ानमय दप ꠱२꠱ ानमु य कृ णाय गीतामृतदहु ेे नम ꠱३꠱ yena tvayā bhārata-taila-pūrṇaḥ prapanna-pārijātāya prajvālito jñāna-mayaḥ pradīpaḥ (2) totra-vetraika-pāṇaye jñāna-mudrāya kṛiṣhṇāya ...by whom the lamp filled with the oil of the gītāmṛita-dhduhenamaḥ (3) Mahabharata was lit with the flame of knowledge. Salutations to Krishna , who blesses the surrendered, in whose hands are a staff and the symbol of knowledge, who milks the Gita's nectar. सवापिनषदाे े गावा े दाधाे गापालनदने ꠰ वसदेवसत देव क सचाणरमदू नम꠰् पाथा े वस सध ीभााेे दधु गीतामृत महत् ꠰꠰ देेवकपरमानद कृ ण वदेे जगु म् ꠱꠱ sarvopaniṣhado gāvo vasudeva-sutam devam dogdhā gopāla-nandanaḥ kaḿsa-cāṇūra-mardanam pārtho vatsaḥ sudhīr bhoktā devakī-paramānandam ddhdugdham gītāmṛitam mahthat (4) kṛiṣhṇam vande jdjagad-gurum (5) The Upanishads are cows, Krishna is the cowherd, I revere Sri Krishna, teacher of all, son of Vasudeva, Arjuna is the calf, and wise people enjoy the sacred destroyer of Kamsa and Chanura, who is the delight nectar milked from the Gita. -

Jnana, Bhakti and Karma Yoga in the Bhagavad Gita

Jnana, Bhakti and Karma Yoga in the Bhagavad Gita The Bhagavad Gita - written between 600 -500 BCE is sometimes referred to as the last Upanishad. As with many Yoga texts and great literature there are many possible layers of meaning. In essence it is grounded by the meditative understanding of the underlying unity of life presented in the Upanishads, and then extends this into how yoga practice, insight and living life can become one and the same. Ultimately it is a text that describes how yoga can clarify our perception of life, its purpose and its challenges, and offers guidance as to how we might understand and negotiate them. It encourages full engagement with life, and its difficulties and dilemmas are turned into the manure for potential liberation and freedom. The Bhagavad-Gita is actually a sub story contained within a huge poem/story called the Mahabharata, one of the ‘Puranas’ or epics that make up much of early Indian literature. It emphasises the importance of engagement in the world, perhaps a reaction to the tendency developing at the time in Buddhism and Vedanta to renounce worldly life in favour of personal liberation. The yoga of the Bhagavad-Gita essentially suggests that fully engaging in all aspects of life and its challenges with a clear perspective is a valid yogic path and possibly superior to meditative realisation alone. There is an implication in this emphasis that there is a potential danger for some people of using yoga practice and lifestyle to avoid difficulties in life and not engage with the world and the culture and time we find ourselves in; and/or perhaps to misunderstand that yoga practice is partly practice for something – to re-evaluate and hopefully enrich our relationship to the rest of life. -

An Understanding of Maya: the Philosophies of Sankara, Ramanuja and Madhva

An understanding of Maya: The philosophies of Sankara, Ramanuja and Madhva Department of Religion studies Theology University of Pretoria By: John Whitehead 12083802 Supervisor: Dr M Sukdaven 2019 Declaration Declaration of Plagiarism 1. I understand what plagiarism means and I am aware of the university’s policy in this regard. 2. I declare that this Dissertation is my own work. 3. I did not make use of another student’s previous work and I submit this as my own words. 4. I did not allow anyone to copy this work with the intention of presenting it as their own work. I, John Derrick Whitehead hereby declare that the following Dissertation is my own work and that I duly recognized and listed all sources for this study. Date: 3 December 2019 Student number: u12083802 __________________________ 2 Foreword I started my MTh and was unsure of a topic to cover. I knew that Hinduism was the religion I was interested in. Dr. Sukdaven suggested that I embark on the study of the concept of Maya. Although this concept provided a challenge for me and my faith, I wish to thank Dr. Sukdaven for giving me the opportunity to cover such a deep philosophical concept in Hinduism. This concept Maya is deeper than one expects and has broaden and enlightened my mind. Even though this was a difficult theme to cover it did however, give me a clearer understanding of how the world is seen in Hinduism. 3 List of Abbreviations AD Anno Domini BC Before Christ BCE Before Common Era BS Brahmasutra Upanishad BSB Brahmasutra Upanishad with commentary of Sankara BU Brhadaranyaka Upanishad with commentary of Sankara CE Common Era EW Emperical World GB Gitabhasya of Shankara GK Gaudapada Karikas Rg Rig Veda SBH Sribhasya of Ramanuja Svet. -

225 Poems from the Rig-Veda (Translated from Sanskrit And

Arts and Economics 225 Poems from the Rig-veda (Translated from Sanskrit and annotated by Paul Thieme) ["Gedichte aus dem Rig-Veda"] (Aus dem Sanskrit iibertragen und erHi.utert von Paul Thieme) 1964; 79 p. Nala and Damayanti. An Episode from the Mahabharata (Translated from Sanskrit and annotated by Albrecht Wezler) ["Nala und Damayanti. Eine Episode aus dem Mahabharata"] (Aus dem Sanskrit iibertragen und erHi.utert von Albrecht Wezler) 1965; 87 p. (UNESCO Sammlung reprasentativer Werke; Asiatische Reihe) Stuttgart: Verlag Philipp Reclam jun. These two small volumes are the first translations from Sanskrit in the "Unesco Collection of Representative Works; Asiatic Series", which the Reclam Verlag has to publish. The selection from the Rig-veda, made by one of the best European ~xperts, presents the abundantly annotated German translation of 'D~ Songs after a profound introduction on the origin and nature of the .Q.lg-veda. Wezler's Nala translation presents the famous episode in simple German prose, and is likewise provided with numerous explanatory notes. Professor Dr. Hermann Berger RIEM:SCHNEIDER, MARCARETE 'l'he World of the mttites (W.ith a Foreword by Helmuth Th. Bossert. Great Cultures of Anti ~~l~y, Vol. 1) [ ~le Welt der Hethiter"] ~M~t einem Vorwort von Helmuth Th. Bossert. GroBe Kulturen der ruhzeit, Band 1) ~~u8ttgart: J. G. Cotta'sche Buchhandlung, 7th Edition 1965; 260 p., plates ~:e bOok un~er review has achieved seven editions in little more than th ~ears, a SIgn that it supplied a wide circle of readers not only with in: Information they need, but it has also been able to awaken lIit~~;st. -

TEACHING HATHA YOGA Teaching Hatha Yoga

TEACHING HATHA YOGA Teaching Hatha Yoga ii Teaching Hatha Yoga TEACHING HATHA YOGA ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Daniel Clement with Naomi Clement Illustrations by Naomi Clement 2007 – Open Source Yoga – Gabriola Island, British Columbia, Canada iii Teaching Hatha Yoga Copyright © 2007 Daniel Clement All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in, or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior written consent of the copyright owner, except for brief reviews. First printing October 2007, second printing 2008, third printing 2009, fourth printing 2010, fifth printing 2011. Contact the publisher on the web at www.opensourceyoga.ca ISBN: 978-0-9735820-9-3 iv Teaching Hatha Yoga Table of Contents · Preface: My Story................................................................................................viii · Acknowledgments...................................................................................................ix · About This Manual.................................................................................................ix · About Owning Yoga................................................................................................xi · Reading/Resources................................................................................................xii PHILOSOPHY, LIFESTYLE & ETHICS.........................................................................xiii -

The Cosmic Teeth. Part

THE COS.AIIC TEETH BY LAWRENCE PARMLY BROWN //. Flame Teeth and the Teeth of the Sun IT' \'ERYWHERE and always fire has been conceived as some- -—-^ thing that consumes, devours or eats hke a hungry animal or human being; and the more or less individualized flames of fire are sometimes viewed as teeth, but more commonly as tongues. In the very ancient Hindu Rig-Veda the god Agni primarily rep- resents ordinary fire, but secondarily the fiery sun; and there it is said that "He crops the dry ground strewn (with grass and wood), like an animal grazing, he with a golden beard, with shining teeth" (Mandala V, Sukta VH, 7; translation of H. H. Wilson, Vol. HI, p. 247), while his light "quickly spreads over the earth, when with his teeth (of flame) he devours his food" {Ih. VH, iii, 4; Wilson's, Vol. IV, p. 36).^ The Mexican goddess of devouring fire is called Chantico ("In- the-house," with reference to her character as divinity of the do- mestic hearth) and also Ouaxolotl ("Split-at-the-top," for the flame divided into two tips) and Tlappalo ("She-of-the-red-butterfly," perhaps from the flame-like flickering of the insect). Her image is described by Duran with open mouth and the prominent teeth of a carnivorous beast ; and she is associated with the dog as a biting animal, according to one account having been transformed into a dog as a punishment for disregarding a prohibition relating to sac- rifices (Seler, J^aticanus B, p. 273; Spence, Gods of Mexico, p. -

A) Karma – Phala – Prepsu : (Ragi) • One Who Has Predominate Desire for Result of Action for Veidica Or Laukika Karma

BHAGAVAD GITA Chapter 18 Moksa Sannyasa Yoga (Final Revelations of the Ultimate Truth) 1 Chapter 18 Moksa Sannyasa Yoga (Means of Liberation) Summary Verse 1 - 12 Verse 18 - 40 Verse 50 - 55 Verse 63 - 66 - Difference Jnana Yoga - Final Summary 3 Types of : between (Meditation) - Be my devotee 1) Jnanam – Knowledge Sannyasa + Tyaga. be my worshipper 2) Karma – Action surrender to me 3) Karta – Doer - Being established and do your duty. Verse 13 - 17 4) Buddhi – Intellect in Brahman’s 5) Drithi – will Nature he becomes 6) Sukham – Happiness free from Desire. Verse 67 - 73 Jnana Yoga Verse 56 - 62 Verse 41 - 49 - Lords concluding - 5 factors in all remarks. actions. Karma Yoga - Body, Prana, Karma Yoga (Svadharma) (Devotion) Mind, Sense Verse 74 - 78 organs, Ego + - Purified seeker who Presiding dieties. - Constantly is detached and self - Sanjayas remember Lord. controlled attains Conclusion. Moksa 2 Introduction : 1) Mahavakya – Asi Padartham 3rd Shatkam Chapter 13, 14, 15 Chapter 16, 17 Chapter 18 - Self knowledge. - Values to make mind fit - Difference between for knowledge. Sannyasa and Tyaga. 2) Subject matter of Gita Brahma Vidya Yoga Sastra - Means of preparing for - Tat Tvam Asi Brahma Vidya. - Identity of Jiva the - Karma in keeping with individual and Isvara the dharma done with Lord. proper attitude. - It includes a life of renunciation. 3 3) 2 Lifestyles for Moksa Sannyasa Karma Renunciation Activity 4) Question of Arjuna : • What is difference between Sannyasa (Renunciation) and Tyaga (Abandonment). Questions of Arjuna : Arjuna said : If it be thought by you that ‘knowledge’ is superior to ‘action’, O Janardana, why then, do you, O Kesava, engage me in this terrible action? [Chapter 3 – Verse 1] With this apparently perplexing speech you confuse, as it were, my understanding; therefore, tell me that ‘one’ way by which, I, for certain, may attain the Highest. -

Satya Studio

Satya Studio http://www.satyasattva.com/ Enneagram of Personality Workshop and Classes Satya Sattva is a Mind & Body wellness center, spiritual and esoteric study group, and a school of thought. We provide classes and workshops in modern & traditional Yoga, Meditation, Qigong and Tai Chi, and Eastern philosophy. Dr. Adina Riposan-Taylor Dr. Adina Riposan-Taylor (Saraswati Devi) is the founder of Satya Sattva Saraswati Devi studio and study group. Adina is life-time committed to self-development practice and study, such as Yoga and Meditation, Qigong and Tai Chi, George I. Gurdjieff was an philosophy and contemplative comparative studies in Buddhism, influential spiritual teacher Hinduism, Shivaism, Sufism, Taoism, and Christianity, as well as self- of the early to mid-20th inQuiry and Transpersonal Psychology. century who believed that most human beings lived Adina studied the Enneagram of Personality system for two years and their lives in a state of she was part of an Enneagram study group for over five years. She has hypnotic "waking sleep", further chosen the Enneagram self-development practice as one of but that it was possible the main reflection and self-awareness disciplines in her psychological to transcend to a higher and spiritual paths towards enlightenment. state of consciousness, and to achieve full human Adina has practiced Meditation for 22 years and Yoga for 15 years, in potential. He taught the several countries in Europe, as well as in the USA. Her experience Enneagram aiming to bring covers a wide variety of yoga branches and styles, such as Hatha Yoga, self-awareness in people's Kriya Yoga, Kundalini Yoga, Jnana Yoga, Raja Yoga, Tantra Yoga, daily lives and humanity's Vinyasa and Ashtanga Yoga. -

Philosophy of Bhagavad-Gita

PHILOSOPHY OF BHAGAVAD-GITA T. SUBBA BOW THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE BHAGAVAD-GITA Copyright Registered All Rights Reserved Permission for translations will be given BY THEOSOPHICAL PUBLISHING HOUSE Adyar, Madras, India THE PHILOSOPHY OF THE BHAGAVAD-GITA BY T. STJBBA ROW Four Lectures delivered at the Eleventh Annual Convention of the Theosophical Society, held at Adyar, on December 27, 28, 29 and 30, 1886 (Second Edition") THEOSOPHICAL PUBLISHING HOUSE ADYAR, MADRAS, INDIA 1921 T. SUBBA ROW AN APPRECIATION MY acquaintance with T. Subba Row began at the end of 1884, when I came here to Madras and settled down with the intention of practising in the High Court. It was at the Theosophical Convention of 1884 that I first met him, and from the very first moment became so deeply attracted to him as to make it difficult for me to understand why it was so. My admiration of his ability was so great that I began to look upon him almost from that time as a great man. He was a very well-made robust man, and strikingly intellectual. When H. P. B. was here, he was known to be a great favourite of hers. It was said that he first attracted " her attention by a paper called The Twelve Signs of the Zodiao ", which was afterwards published. At the Convention, there was much talk on various topics, and he always spoke with decision, and his views carried great weight. But he spoke little and only what was necessary. There was then a small committee of which Colonel Olcott was the Presi- dent. -

The Upanishads

The Upanishads The Breath of the Eternal A free download book compiled from the best sources on the web Hotbook and Criaturas Digitais Studio Rio de janeiro - Brazil Index 01 Brief Introduction to the Upanishads 02 Vedas and the Upanishads 03 The 15 principals Upanishads ---------------------------------------------------- 04 KATHA Upanishad 05 ISHA Upanishad 06 KENA Upanishad 07 MAITRAYANA-BRAHMAYA Upanishad 08 Kaivalya Upanishad 09 Vajrasuchika Upanishad 10 MANDUKYA Upanishad 11 MUNDAKA Upanishad 12 Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 13 KHANDOGYA Upanishad 14 KAUSHITAKI Upanishad 15 PRASHNA Upanishad 16 SHVETASHVATARA Upanishad 17 AITAREYA Upanishad 18 TAITTIRIYA Upanishad -------------------------------------------------------- 19 Atman - The Soul Eternal 20 Upanishads: Universal Insights 21 List of 108 Upanishads Brief Introduction to the Upanishads Collectively, the Upanishads are known as Vedanta (end of the vedas). The name has struck, because they constitute the concluding part of the Vedas. The word 'upanishad' is derived from a combination of three words, namely upa+ni+sad. 'Upa' means near, 'ni' means down and 'sad' means to sit. In ancient India the knowledge of the Upanishads was imparted to students of highest merit only and that also after they spent considerable time with their teachers and proved their sincerity beyond doubt. Once the selection was done, the students were allowed to approach their teachers and receive the secret doctrine from them directly. Since the knowledge was imparted when the students sat down near their teachers and listened to them, the word 'Upanishad', became vogue. The Upanishads played a very significant role in the evolution of ancient Indian thought. Many schools of Hindu philosophy, sectarian movements and even the later day religions like Buddhism and Jainism derived richly from the vast body of knowledge contained in the Upanishads.