An Introduction to Buddhist Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Unravelling of the Dharma-Dharmat- Vibhga-Vrtti of Vasubandhu

An unravelling of the Dharma-dharmat- vibhga-vrtti of Vasubandhu Autor(en): Anacker, Stefan Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Asiatische Studien : Zeitschrift der Schweizerischen Asiengesellschaft = Études asiatiques : revue de la Société Suisse-Asie Band (Jahr): 46 (1992) Heft 1: Études bouddhiques offertes à Jacques May PDF erstellt am: 28.09.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-146946 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst -

Thinking in Buddhism: Nagarjuna's Middle

Thinking in Buddhism: Nagarjuna’s Middle Way 1994 Jonah Winters About this Book Any research into a school of thought whose texts are in a foreign language encounters certain difficulties in deciding which words to translate and which ones to leave in the original. It is all the more of an issue when the texts in question are from a language ancient and quite unlike our own. Most of the texts on which this thesis are based were written in two languages: the earliest texts of Buddhism were written in a simplified form of Sanskrit called Pali, and most Indian texts of Madhyamika were written in either classical or “hybrid” Sanskrit. Terms in these two languages are often different but recognizable, e.g. “dhamma” in Pali and “dharma” in Sanskrit. For the sake of coherency, all such terms are given in their Sanskrit form, even when that may entail changing a term when presenting a quote from Pali. Since this thesis is not intended to be a specialized research document for a select audience, terms have been translated whenever possible,even when the subtletiesof the Sanskrit term are lost in translation.In a research paper as limited as this, those subtleties are often almost irrelevant.For example, it is sufficient to translate “dharma” as either “Law” or “elements” without delving into its multiplicity of meanings in Sanskrit. Only four terms have been left consistently untranslated. “Karma” and “nirvana” are now to be found in any English dictionary, and so their translation or italicization is unnecessary. Similarly, “Buddha,” while literally a Sanskrit term meaning “awakened,” is left untranslated and unitalicized due to its titular nature and its familiarity. -

Jichihan and the Restoration and Innovation of Buddhist Practice

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1999 26/1-2 Jichihan and the Restoration and Innovation of Buddhist Practice Marc Buijnsters The various developments in doctrinal thought and practice during the Insei and Kamakura periods remain one of the most intensively researched fields in the study of Japanese Buddhism. Two of these developments con cern the attempts to restore the observance of traditional Buddhist ethics, and the problem of how Pure La n d tenets could be inserted into the esoteric teaching. A pivotal role in both developments has been attributed to the late-Heian monk Jichihan, who was lauded by the renowned Kegon scholar- monk Gydnen as “the restorer of the traditional precepts ” and patriarch of Japanese Pure La n d Buddhism.,’ At first glance, available sources such as Jichihan’s biograpmes hardly seem to justify these praises. Several newly discovered texts and a more extensive use of various historical sources, however, should make it possible to provide us with a much more accurate and complete picture of Jichihan’s contribution to the restoration and innovation of Buddhist practice. Keywords: Jichihan — esoteric Pure Land thousfht — Buddhist reform — Buddhist precepts As was n o t unusual in the late Heian period, the retired Regent- Chancellor Fujiwara no Tadazane 藤 原 忠 実 (1078-1162) renounced the world at the age of sixty-three and received his first Buddnist ordi nation, thus entering religious life. At tms ceremony the priest Jichi han officiated as Teacher of the Precepts (kaishi 戒自帀;Kofukuji ryaku 興福寺略年代記,Hoen 6/10/2). Fujiwara no Yorinaga 藤原頼長 (1120-11^)0), Tadazane^ son who was to be remembered as “Ih e Wicked Minister of the Left” for his role in the Hogen Insurrection (115bハ occasionally mentions in his diary that he had the same Jichi han perform esoteric rituals in order to recover from a chronic ill ness, achieve longevity,and extinguish his sins (Taiki 台gd Koji 1/8/6, 2/2/22; Ten,y6 1/6/10). -

Studies in Buddhist Hetuvidyā (Epistemology and Logic ) in Europe and Russia

Nataliya Kanaeva STUDIES IN BUDDHIST HETUVIDYĀ (EPISTEMOLOGY AND LOGIC ) IN EUROPE AND RUSSIA Working Paper WP20/2015/01 Series WP20 Philosophy of Culture and Cultural Studies Moscow 2015 УДК 24 ББК 86.36 K19 Editor of the series WP20 «Philosophy of Culture and Cultural Studies» Vitaly Kurennoy Kanaeva, Nataliya. K19 Studies in Buddhist Hetuvidyā (Epistemology and Logic ) in Europe and Russia [Text] : Working paper WP20/2015/01 / N. Kanaeva ; National Research University Higher School of Economics. – Moscow : Higher School of Economics Publ. House, 2015. – (Series WP20 “Philosophy of Culture and Cultural Studiesˮ) – 52 p. – 20 copies. This publication presents an overview of the situation in studies of Buddhist epistemology and logic in Western Europe and in Russia. Those studies are the young direction of Buddhology, and they started only at the beginning of the XX century. There are considered the main schools, their representatives, the directions of their researches and achievements in the review. The activity of Russian scientists in this field was not looked through ever before. УДК 24 ББК 86.36 This study (research grant № 14-01-0006) was supported by The National Research University Higher School of Economics (Moscow). Academic Fund Program in 2014–2015. Kanaeva Nataliya – National Research University Higher School of Economics (Moscow). Department of Humanities. School of Philosophy. Assistant professor; [email protected]. Канаева, Н. А. Исследования буддийской хетувидьи (эпистемологии и логики) в Европе и России (обзор) [Текст] : препринт WP20/2015/01 / Н. А. Канаева ; Нац. исслед. ун-т «Высшая школа экономи- ки». – М.: Изд. дом Высшей школы экономики, 2015. – (Серия WP20 «Философия и исследо- вания культуры»). -

APA Newsletter on Asian and Asian-American Philosophers And

NEWSLETTER | The American Philosophical Association Asian and Asian-American Philosophers and Philosophies FALL 2018 VOLUME 18 | NUMBER 1 Prasanta Bandyopadhyay and R. Venkata FROM THE EDITOR Raghavan Prasanta S. Bandyopadhyay Some Critical Remarks on Kisor SUBMISSION GUIDELINES AND Chakrabarti’s Idea of “Observational INFORMATION Credibility” and Its Role in Solving the Problem of Induction BUDDHISM Kisor K. Chakrabarti Madhumita Chattopadhyay Some Thoughts on the Problem of Locating Early Buddhist Logic in Pāli Induction Literature PHILOSOPHY OF LANGUAGE Rafal Stepien AND GRAMMAR Do Good Philosophers Argue? A Buddhist Approach to Philosophy and Philosophy Sanjit Chakraborty Prizes Remnants of Words in Indian Grammar ONTOLOGY, LOGIC, AND APA PANEL ON DIVERSITY EPISTEMOLOGY Ethan Mills Pradeep P. Gokhale Report on an APA Panel: Diversity in Īśvaravāda: A Critique Philosophy Palash Sarkar BOOK REVIEW Cārvākism Redivivus Minds without Fear: Philosophy in the Indian Renaissance Reviewed by Brian A. Hatcher VOLUME 18 | NUMBER 1 FALL 2018 © 2018 BY THE AMERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL ASSOCIATION ISSN 2155-9708 APA NEWSLETTER ON Asian and Asian-American Philosophy and Philosophers PRASANTA BANDYOPADHYAY, EDITOR VOLUME 18 | NUMBER 1 | FALL 2018 opponent equally. He pleads for the need for this sort of FROM THE EDITOR role of humanism to be incorporated into Western analytic philosophy. This incorporation, he contends, has a far- Prasanta S. Bandyopadhyay reaching impact on both private and public lives of human MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY beings where the love of wisdom should go together with care and love for fellow human beings. The fall 2018 issue of the newsletter is animated by the goal of reaching a wider audience. Papers deal with issues SECTION 2: ONTOLOGY, LOGIC, AND mostly from classical Indian philosophy, with the exception EPISTEMOLOGY of a report on the 2018 APA Eastern Division meeting panel on “Diversity in Philosophy” and a review of a book about This is the longest part of this issue. -

Buddhist Bibio

Recommended Books Revised March 30, 2013 The books listed below represent a small selection of some of the key texts in each category. The name(s) provided below each title designate either the primary author, editor, or translator. Introductions Buddhism: A Very Short Introduction Damien Keown Taking the Path of Zen !!!!!!!! Robert Aitken Everyday Zen !!!!!!!!! Charlotte Joko Beck Start Where You Are !!!!!!!! Pema Chodron The Eight Gates of Zen !!!!!!!! John Daido Loori Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind !!!!!!! Shunryu Suzuki Buddhism Without Beliefs: A Contemporary Guide to Awakening ! Stephen Batchelor The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching: Transforming Suffering into Peace, Joy, and Liberation!!!!!!!!! Thich Nhat Hanh Buddhism For Beginners !!!!!!! Thubten Chodron The Buddha and His Teachings !!!!!! Sherab Chödzin Kohn and Samuel Bercholz The Spirit of the Buddha !!!!!!! Martine Batchelor 1 Meditation and Zen Practice Mindfulness in Plain English ! ! ! ! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana The Four Foundations of Mindfulness in Plain English !!! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana Change Your Mind: A Practical Guide to Buddhist Meditation ! Paramananda Making Space: Creating a Home Meditation Practice !!!! Thich Nhat Hanh The Heart of Buddhist Meditation !!!!!! Thera Nyanaponika Meditation for Beginners !!!!!!! Jack Kornfield Being Nobody, Going Nowhere: Meditations on the Buddhist Path !! Ayya Khema The Miracle of Mindfulness: An Introduction to the Practice of Meditation Thich Nhat Hanh Zen Meditation in Plain English !!!!!!! John Daishin Buksbazen and Peter -

18 Phases Or Realms

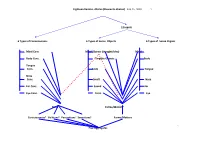

Eighteen Realms- dhatus (Elements-dhatus) Feb.16, 2020 1. 12 inputs 6 Types of Consciousness 6 Types of Sense Objects 6 Types of Sense Organs Mind Cons. Mind Objects (thought/idea) Mind Body Cons. Tangible Objects Body Tongue Cons. Taste Tongue Nose Cons. Smell Nose Ear Cons. Sound Ear Eye Cons. Form Eye Mind Forms/Matters1 Consciousness5 Volitions4 Perceptions3 Sensations2 Forms/Matters . Five Aggregates P2. 1. Rupa: Form or (Matter) Aggregate: the Four Great Elements: 1) Solidity, 2) Fluidity, 3) Heat, 4) Wind/Motion which include the five physical sense-organs i.e. the faculties of the eye, ear, nose, tongue, body besides the brain/mind (note: the brain is an organ, not the mind which is an abstract noun). These sense organs are in contact with the external objects of visible form, sound, odor, taste and tangible things and the mind faculty which corresponds to the intangible objects such as thoughts, ideas, and conceptions. 2. Vedana: Sensations- Feelings (generated by the 6 sense organs eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, brain/mind) 3. Samjna: Perception (Conception): The mental function of shape, color, length, pain, pleasure, un-pleasure, neutral. 4. Samskara: Volition-Mental formation: i.e. flashback, will, intention, or the mental function that accounts for craving. 5. Vijnana : Consciousness( Cognition, discrimination-Mano consciousness): the respective consciousness arises when 6 sense organs eye , ear, nose, tongue, body, brain/mind are in contact with the 6 sense objects form , sound, smell, taste, tangible objects , and mental objects. Please be note that Vijnana Consciousness can be further classified into the 6th, 7th and the 8th according to the Vijhanavada (Mere-Mind) School: Mano Consciousness (6th Consciousness): The front 5 senses report to and co-ordinate by the 6th senses in reaction to the 6 sense objects, gather sense data, discriminate, recall it’s the active, coarse and manifest portion of the Manas Vijnanna. -

The Role of Buddhism in the Changing Life of Rural Women in Sri Lanka Since Independence

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 1-1-2002 The role of Buddhism in the changing life of rural women in Sri Lanka since independence Lalani Weddikkara Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Weddikkara, L. (2002). The role of Buddhism in the changing life of rural women in Sri Lanka since independence. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/746 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/746 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. -

Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism, Revised Edition

REVISED EDITION John Powers ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 1 Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 2 ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 3 Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism revised edition by John Powers Snow Lion Publications ithaca, new york • boulder, colorado ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 4 Snow Lion Publications P.O. Box 6483 • Ithaca, NY 14851 USA (607) 273-8519 • www.snowlionpub.com © 1995, 2007 by John Powers All rights reserved. First edition 1995 Second edition 2007 No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means without prior written permission from the publisher. Printed in Canada on acid-free recycled paper. Designed and typeset by Gopa & Ted2, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Powers, John, 1957- Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism / by John Powers. — Rev. ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN-13: 978-1-55939-282-2 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-55939-282-7 (alk. paper) 1. Buddhism—China—Tibet. 2. Tibet (China)—Religion. I. Title. BQ7604.P69 2007 294.3’923—dc22 2007019309 ITTB_Interior 9/20/07 2:23 PM Page 5 Table of Contents Preface 11 Technical Note 17 Introduction 21 Part One: The Indian Background 1. Buddhism in India 31 The Buddha 31 The Buddha’s Life and Lives 34 Epilogue 56 2. Some Important Buddhist Doctrines 63 Cyclic Existence 63 Appearance and Reality 71 3. Meditation 81 The Role of Meditation in Indian and Tibetan Buddhism 81 Stabilizing and Analytical Meditation 85 The Five Buddhist Paths 91 4. -

Buddhist Ethical Education.Pdf

BUDDHIST ETHICAL EDUCATION ADVISORY BOARD His Holiness Thich Tri Quang Deputy Sangharaja of Vietnam Most Ven. Dr. Thich Thien Nhon President of National Vietnam Buddhist Sangha Most Ven.Prof. Brahmapundit President of International Council for Day of Vesak CONFERENCE COMMITTEE Prof. Dr. Le Manh That, Vietnam Most Ven. Dr. Dharmaratana, France Most Ven. Prof. Dr. Phra Rajapariyatkavi, Thailand Bhante. Chao Chu, U.S.A. Prof. Dr. Amajiva Lochan, India Most Ven. Dr. Thich Nhat Tu (Conference Coordinator), Vietnam EDITORIAL BOARD Dr. Do Kim Them, Germany Dr. Tran Tien Khanh, USA Nguyen Manh Dat, U.S.A. Bruce Robert Newton, Australia Dr. Le Thanh Binh, Vietnam Giac Thanh Ha, Vietnam Nguyen Thi Linh Da, Vietnam Giac Hai Hanh, Australia Tan Bao Ngoc, Vietnam VIETNAM BUDDHIST UNIVERITY SERIES BUDDHIST ETHICAL EDUCATION Editor Most Ven. Thich Nhat Tu, D.Phil., HONG DUC PUBLISHING HOUSE CONTENTS Foreword .................................................................................................vii Preface ......................................................................................................ix Editor’s Foreword .................................................................................xiii 1. ‘Nalanda Culture’ as an Archetypal of Global Education in Ethics: An Approach Anand Singh ...............................................................................................1 2. Buddhist Education: Path Leading to the Awakening Hira Paul Gangnegi .................................................................................15 -

To Be Wise and Kind

To be wise and kind: a Buddhist community engagement with Victorian state primary schools A thesis submitted in total fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Sue Erica Smith School of Education Faculty of Arts, Education and Human Development Victoria University March 2010 Doctor of Philosophy Declaration I, Sue Erica Smith, declare that the PhD thesis entitled To be wise and kind: a Buddhist community engagement with Victorian state primary schools is no more that 100,000 words in length including quotes and exclusive of tables, figures, appendices, bibliography, references and footnotes. This thesis contains no material that has been submitted previously, in whole or in part, for the award of any other academic degree or diploma. Except where otherwise indicated, this thesis is my own work. Signature Date Acknowledgements This study would not have arisen without the love, support, inspiration and guidance from many people to whom I wish to express my deepest gratitude: x my Dharma teachers Lama Thubten Yeshe, Zasep Rinpoche, Traleg Rinpoche and Geshe Doga especially, who show by their examples the wondrous capacity of what we all can be, x my parents Ron and Betty Smith, who have not always understood what I have been doing, but have unfailingly supported and encouraged me to pursue my education, x my principal supervisor Professor Maureen Ryan and my co-supervisor Dr Merryn Davies for their skilful guidance, x my critical friends Ven. Chonyi Dr Diana Taylor and Dr Saman Fernando on points of Dharma/ -

The Special Theory of Pratītyasamutpāda: the Cycle Of

THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF BUDDHIST STUDIES EDITOR-IN-CHIEF A.K. Narain University of Wisconsin, Madison, USA EDITORS tL. M.Joshi Ernst Steinkellner Punjabi University University oj Vienna Patiala, India Wien, Austria Alexander W. Macdonald Jikido Takasaki Universile de Paris X University of Tokyo Nanterre, France Tokyo, Japan Bardwell Smith Robert Thurman Carleton College Amherst College Northfield, Minnesota, USA Amherst, Massachusetts, USA ASSISTANT EDITOR Roger Jackson Fairfield University Fairfield, Connecticut, USA Volume 9 1986 Number 1 CONTENTS I. ARTICLES The Meaning of Vijnapti in Vasubandhu's Concept of M ind, by Bruce Cameron Hall 7 "Signless" Meditations in Pali Buddhism, by Peter Harvey 2 5 Dogen Casts Off "What": An Analysis of Shinjin Datsuraku, by Steven Heine 53 Buddhism and the Caste System, by Y. Krishan 71 The Early Chinese Buddhist Understanding of the Psyche: Chen Hui's Commentary on the Yin Chihju Ching, by Whalen Im 85 The Special Theory of Pratityasamutpdda: The Cycle of Dependent Origination, by Geshe Lhundub Sopa 105 II. BOOK REVIEWS Chinese Religions in Western Languages: A Comprehensive and Classified Bibliography of Publications in English, French and German through 1980, by Laurence G. Thompson (Yves Hervouet) 121 The Cycle of Day and Night, by Namkhai Norbu (A.W. Hanson-Barber) 122 Dharma and Gospel: Two Ways of Seeing, edited by Rev. G.W. Houston (Christopher Chappie) 123 Meditation on Emptiness, by Jeffrey Hopkins Q.W. de Jong) 124 5. Philosophy of Mind in Sixth Century China, Paramdrtha 's 'Evolution of Consciousness,' by Diana Y. Paul (J.W.deJong) 129 Diana Paul Replies 133 J.W.deJong Replies 135 6.